Qatar’s Sports Diplomacy Project

Since the start of the century, and in particular within the last decade, Qatar has taken steps to establish itself as a sporting nation as part of a wider drive to improve its international profile. A huge part of this drive has been its focus on the footballing sphere. The Qatari approach to ‘football diplomacy’ can be broken down into three core elements that serve complementary purposes on the global stage.

Qatar has taken steps towards firstly increasing domestic talent, secondly attracting overseas investment and sponsorships, and lastly hosting a wide array of sporting events, most notably the 2022 World Cup.

Increasing Domestic Talent

Qatar has invested large sums of money in internal talent development. In 2004, the multidisciplinary Aspire Academies were founded by Emirati decree – an order from Qatar’s head monarch. The royal family’s involvement in Qatari sports policy, as well as the concerted longevity of its sports policy, emphasises and underlines its strategic nature.

Photo: Aspire Academy

The academies themselves have been remarkably successful. Fifteen years on from their advent, results are steadily starting to show. Qatar’s surprise success at the 2019 Asian Cup was testament to the academies’ quality. Top scorer at the tournament and Qatar’s star striker, Almoez Ali, is an Aspire alumnus.

In 2014, a team composed entirely of ex-Aspire students won the 2014 U1-9 AFC Asian Cup. Whilst Qatar didn’t advance from the group stages of the 2019 Copa América, they didn’t have an awful tournament either, drawing 2-2 with Paraguay and losing twice: 1-0 to Colombia and 2-0 to Argentina. Ten years previously, such score lines would have been unthinkable.

A key figure in their success has been Felix Sanchez Bas, an ex-Barcelona youth coach who moved to Qatar in 2006 to help with the development of players in the Aspire academies. Alongside some of his graduates, he oversaw the under-19s 2014 success and the Asian Cup victory, before being promoted to managing the U-23s and then the first team in 2017. Bas’s football pedigree and thorough understanding of the Qatari system and its players make him a shrewd appointment, and he currently boasts a 57% win-rate as Qatar’s head coach.

At time of writing, Qatar sit in 55th place on the FIFA World Rankings, sandwiched between Greece and Mali. This is much improved from its 2010 rank of 112. It’s likely that by the time the World Cup rolls around, it won’t be the lowest-ranked host ever, as many reports pointed out when Qatar was granted hosting duties.

Overseas Investment and Sponsorship

Secondly, Qatar has purchased influence globally, giving it a global ‘brand’ and thus soft power (i.e. the international power of attraction, as opposed to coercion). Its numerous sponsorship deals are evidence of this (Paris Saint-Germain, Barcelona, Bayern Munich, Roma), whilst Qatar Airways’ recent deals with CONMEBOL and Boca Juniors also show strategic consistency, as they complement its other actions, for example hosting the Copa Libertadores final.

The prominent use of state-owned Qatar Airways itself is intriguing, as it not only encourages consideration of Qatar as a tourist destination, it also markets the state as a facilitator of international travel, thereby feeding into a similar narrative that its hosting does – that Qatar is a good global citizen.

Moreover, Qatar is using the World Cup as an opportunity to attract international corporations and foreign direct investment, thereby increasing Qatar’s profile as a burgeoning economic opportunity for overseas investors. A Chinese firm was recently granted the contract for the World Cup’s flagship stadium, for example.

Hosting

Lastly, in efforts that have similar goals and effects to its array of sponsorships, Qatar is putting itself forward as a potential host nation for a variety of events in an attempt to improve its image globally.

Their desire to host a large sporting event and benefit from its byproducts is evidenced by their bids for the 2016 and 2020 Olympics, the 2019 Athletics World Championships, their yearly Grand Prix, and of course the 2022 World Cup. These ambitions can be seen elsewhere in the footballing sphere, too, for example their acquisition of the 2011 Asian Cup, this year’s Club World Cup, and their offer to host the 2018 Copa Libertadores Final.

Photo: David Ramos / FIFA via Getty

Earlier this year, Barney Ronay wrote an astute article for the Guardian exploring ‘sports-washing’ and its intricate presence in today’s global game. “Sportswashing describes the way sport is used to launder a reputation, to gloss a human rights record, to wash a little blood away,” Ronay explained.

Indeed, whilst the sponsorships we see Qatar purchasing globally are part of a more concerted approach to establish Qatar as a small but powerful sporting state and an important global player, they also serve the secondary function of distracting from its shortcomings in terms of human rights. Attention is supposedly drawn to the state as a global sporting influence, rather than to its political wrongdoings.

However, it’s hard to claim sports-washing is the primary reason for event-hosting given other reasons for pursuing major sports events. There’s a reason countries with growing influence and power see sports as a convenient avenue by which to achieve numerous goals.

Qatar’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ entry entitled Sports Diplomacy sheds some light on the supposed aims of its strategy, citing how sport will help ‘development and peace’, infrastructural improvement, legislative changes, and change the ‘image of the Middle East’ by creating an atmosphere of ‘positive interaction between the region and the World’.

Opportunities abound, indeed. This isn’t just a push to cover up the country’s human rights record (though that of course plays a role); it’s more concerted, considered and unmistakably strategic. Being viewed as the positive, welcoming outpost of the region would be a huge accomplishment for the Gulf state, and a huge source of frustration for its neighbours.

With this in mind, it’s important to remember that sports diplomacy initiatives constitute part of wider ‘public diplomacy’ strategies generally aimed towards specific strategic goals. As such, Qatar’s sporting and cultural initiatives should be examined with other diplomatic efforts in mind. The choice by the Qatari government to brand itself as a Gulf-based sporting hub is complemented by its wider initiatives.

Photo: Reuters

Qatar’s foreign policy is in part defined by its location; it’s located in the Middle East and therefore suffers from the so-called ‘neighbourhood effect’; its national image is associated with and affected by regional stereotypes of political instability, despite Qatar being less unstable than some of its neighbours.

Secondly, it is exceptionally small geographically, especially when compared with its largest neighbour, Saudi Arabia. In 2017, a Saudi-led coalition severed ties with Qatar, accusing it of sympathising with terrorists. Whilst one may have expected the small state to fold in on itself (60% of its imports were cut off suddenly), Qatar has instead performed well, expanding ties and investments overseas. Its GDP grew by 1.4% in 2018.

Indeed, Qatar is in something of a unique position in that it is a small state with enormously large supplies of natural resources. It is the world’s largest exporter of liquefied natural gas and has the 14th largest oil reserves worldwide; it also has the highest GDP per capita in the world (which is why it’s so continually disappointing that the country, and especially migrant workers, suffer from huge inequality – the richest 1% of citizens share 29% of pre-tax income). To call it a typical ‘small state’ would be amiss; it has more economic capacity for influence, and survival, than most others.

Regardless, like most small states, Qatar has suffered from a difficulty to impose itself internationally. This is often due to geographic size and resultant perceived weakness, which can result in unequal bilateral relationships (see, for example, Israel and the US, or Nepal and China). In part due to security concerns, but also due to a desire for international recognition, some small states engage in what JE Peterson terms ‘niche exploitation’; the creation of a niche that a state can exploit internationally. See, for example, Switzerland and banking, or Panama and cigars.

The former creates international reliance on the country’s economic stability, the latter creates revenue and a tourism stream. Niche creation often provides some form of service to other states, which in turn increases security, as the international community has a vested interest in the stability of the state in question (namely, that it can continue to provide its valued service).

Given the limited hard power resources of most small states, niche exploitation can be key in leveraging an advantageous position in a competitive global system. Qatar’s attempted niche, in the 21st century, has been to act as an international mediator. This can be seen throughout its foreign policy of the last twenty years. Firstly, the creation of Al-Jazeera (and recently, BeIN Sports) as a way to disseminate news throughout the Arab world. Secondly, Qatar’s willingness to hold cultural and diplomatic events and act as mediator for other states in dispute.

We can see these initiatives paralleled by its efforts in the sporting sphere to brand itself as a helpful, generous and welcoming country. Widespread sponsorship, whilst spreading the Qatari brand, also enables high-quality football by adding huge sums of revenue to clubs popular internationally, thereby improving clubs’ purchasing power and player quality and positioning Qatar as a facilitator of global football.

Moreover, like its neighbour Saudi Arabia, Qatar wants to diversify its economy to prevent over-reliance on natural resources. Sporting events present visitors with an experience of Qatar that they may want to repeat, as the country becomes associated with the jovial carnival atmosphere which is usually present during a World Cup. In addition, visiting fans use local businesses, explore local tourism sites, and see what Qatar ‘has to offer’, so the tournament presents Qatar as a possible future holiday destination and thereby boosts the nation’s tourism industry.

Photo: AFP Photo

Aspire Academies also host foreign teams with summer preparation camps and for example in 2013-14 hosted the youth sections of over 32 clubs, including Liverpool and PSG. This further substantiates the narrative of Qatar as a welcoming host and increases the likelihood of Qatar being viewed as a viable football destination (one of the most common complaints about 2022).

As the world becomes more globalised and the intricately connected stratosphere of international sport continues to change accordingly, opportunities abound for nations that want to improve their international profile. In short, it’s a good opportunity for Qatar to ingratiate itself to a huge audience.

Qatar may rid itself of the ‘neighbourhood effect’ in terms of conflict, yet it remains justifiably associated with the awful triumvirate of homophobia, sexism, and racism. Throw corruption in there and a soft power disaster seems likely, though arguably much of the corruption-related damage to its image has already been done.

Sports-wise, Qatar’s concerted, premeditated approach to preparation and development has laid the foundations for a successful – if bizarre – tournament in 2022. They have plenty of hosting experience to draw upon, so they should be set up well to manage the operational and logistical demands of a World Cup.

But international events remain a double-edged sword for Qatar. International attention, and scrutiny, will only increase in the coming years and months. If it can reform its domestic policies, then that will go a long way to ensuring its international appeal improves accordingly. The human rights of workers and specifically their right to safe working conditions is an issue that won’t go away without genuine change being enacted.

The Club World Cup in January presented an opportunity for the Gulf state to begin to ingratiate itself to attentive football fans worldwide, but substantial overhaul is needed if Qatar is to be widely perceived as an ethical, welcoming nation. Even the way it conducts itself in footballing spheres – especially its big money ownership of PSG and Man City – doesn’t lend itself to perceptions of the Gulf state as caring or tactful.

Sports diplomacy initiatives are a useful tool in a strategic arsenal as they present opportunities for infrastructural, economic, and operational improvements as well as a chance to challenge and direct global narratives. However, if Qatar’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs has learnt anything from its numerous events hosted over the past decade or so, it should perhaps be that those global narratives are difficult to direct, and genuine change is needed in a few important areas if the next decade is to shine kindly upon Qatar’s sporting project.

By: Ewan Morgan

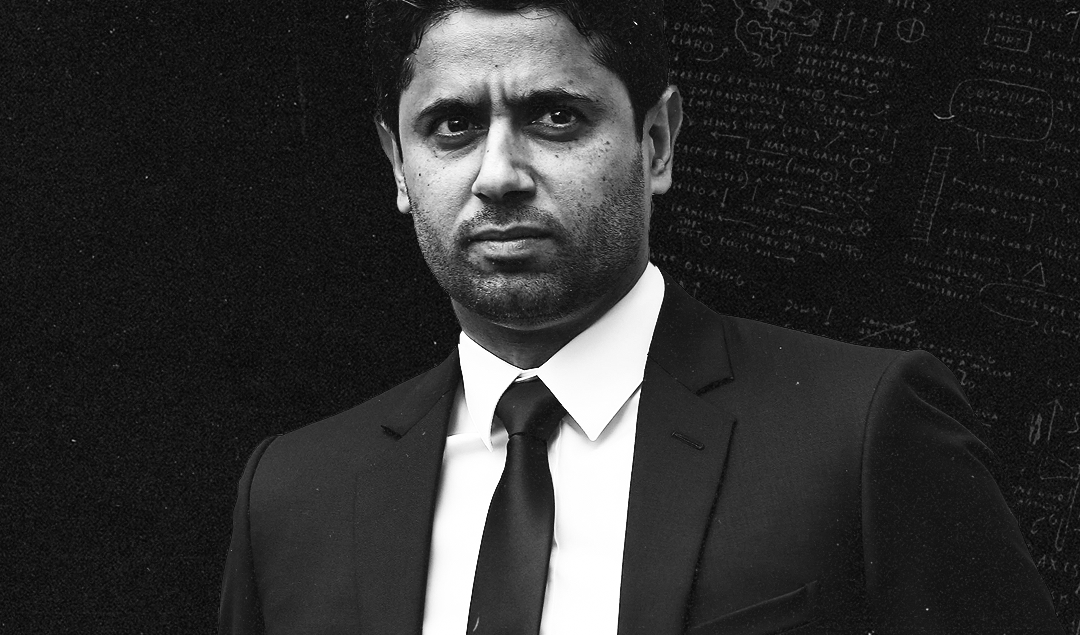

Featured Image: @GabFoligno

This article was originally published on Football Chronicle.