The Manchester Derby: A Tactical Analysis

The Manchester derby wasn’t just a game between the clubs that occupy the first two spots in the Premier League, nor was it a match between the two richest clubs in England, but it was, well and truly, the umpteenth tactical battle between Josè Mourinho and Pep Guardiola – two of the most successful managers in recent years and notorious rivals, their rivalry ascribable to their opposite football philosophies and beliefs – at yet again, one of the theatres of football: Manchester United’s Old Trafford.

Lineups

The starting line-ups didn’t provide any particular surprises, other than Gabriel Jesus’ or Sterling’s – subject addressed in detail later on -selection in preference to Man City’s all-time leading goalscorer Sergio Aguero.

Manchester City (4-3-3): Ederson, Walker, Kompany, Otamendi, Delph; De Bruyne, Fernandinho, Silva; Sanè, Sterling, Jesus.

Manchester United (4-4-1-1): De Gea, Valencia, Smalling, Rojo, Young; Martial, Herrera, Matic, Rashford; Lingard, Lukaku.

United’s man-marking

As often showcased, Mourinho’s approach in big games is to sit deep and counter, and Sunday’s encounter was no different, as United’s focus was on closing down space and transitioning quickly from defence to attack.

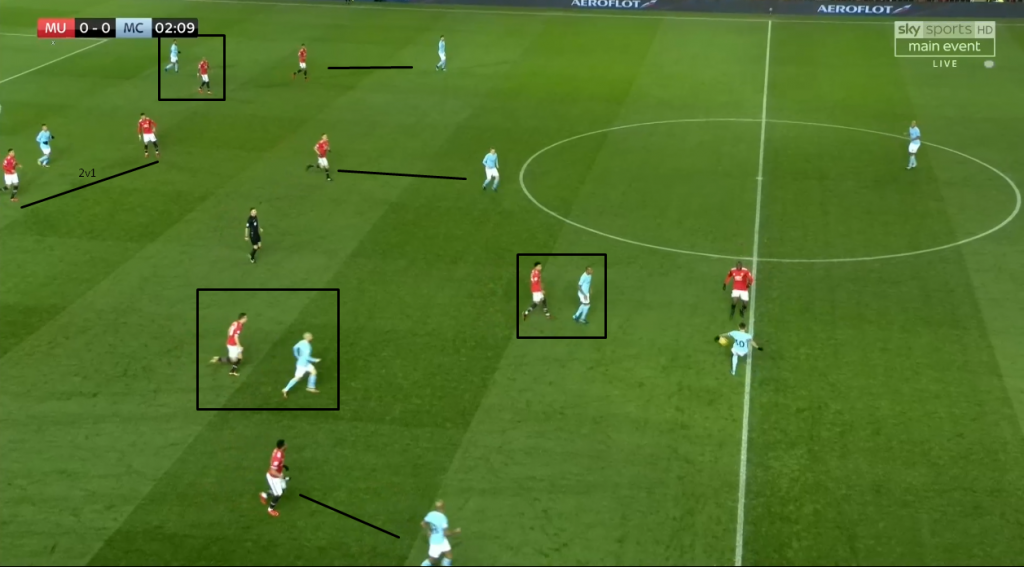

Out of possession, United deployed a 4-4-1-1 deep block with specific man-orientations to hinder City’s build-up. Mourinho’s side allowed the centre-backs time on the ball, albeit limiting every possible passing option by marking the receivers. Lingard would screen/mark Fernandinho and Lukaku would line up beside the Brazilian to crowd the centre, while Matic and Herrera respectively marked De Bruyne and Silva; Rashford and Martial stayed close to the full-backs: Walker and Delph.

United’s man-marking pattern. Otamendi and Kompany are free to circulate whilst all vertical and diagonal passing options are marked.

Another focus from Mourinho’s side was to deny City their trademark runs into depth and cutbacks to the forwards or onrushing midfielders and layoffs between the lines. United successfully denied City these moves by crowding the box with four to six players – usually comprised of the defensive line and Matic and Herrera – which not only provided numerical superiority in almost all situations, but due to the vertical compactness between De Gea and the first and second line, didn’t enable Guardiola’s side to penetrate or shoot either (due to United’s horizontal compactness too).

Guardiola’s positional switches

Initially, City attempted to disrupt United’s man-marking system through runs from the CBs – usually Otamendi, always quite free to carry the ball foward – in order to force a marker out of position and create a free-man situation, however this plan didn’t work as Lukaku would trackback and follow the centre-back; another failed attempt to disorganize the opposing shape was Delph moving infield, option that was quickly discarded since Martial kept following the Englishman.

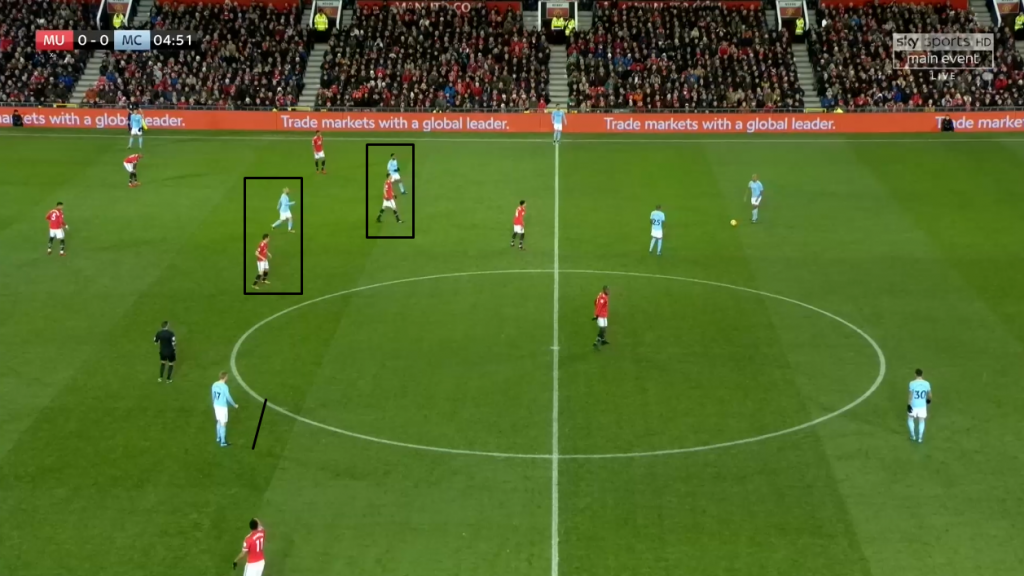

In the 4th minute, Guardiola switched Gabriel Jesus to the left wing, Sanè to the right wing and Sterling centrally, as a false 9. This move allowed City to overload the centre and create a 4v3 as a result of Sterling dropping into midfield. Furthermore, De Bruyne and Silva swapped places, positioning themselves respectively at LCM and RCM; Sterling in a false 9 role allowed City to manipulate United’s man-orientations, with either Matic, Herrera or Lingard having to deal with the English winger when in their zone, consequently freeing one of City’s midfielders from his marker and facilitating build-up play and progression.

Sterling drops into midfield, forcing Matic to mark him whilst De Bruyne and Silva swap positions, allowing the former to act as a free-man.

However, as much as Sterling’s change of position to false 9 helped City’s build-up, it also took the only “striker” away from goal, limiting passing options in advanced central areas (0v2) as Jesus and Sanè focused on providing width and seldom cut inside to occupy more central positions. In addition United’s CBs rarely followed Sterling into midfield (and when done the free space in-behind the CB wasn’t exploited), which ended up creating no superiority situations in the final third.

Guardiola, being a perfectionist, read this situation and rectified it by moving Jesus to the centre when Sterling vacated his position and advancing Fabian Delph, who almost acted as a left-winger. This move led, in fact, to a very good chance for the Citizens, where Sterling, from the left half-space, played a lovely little pass to Jesus, whom, instead of shooting from close range, tried a back-heel for Silva, which was easily cleared by United’s defence.

When a game-plan takes a wrong turn

Mourinho’s offensive game-plan was less elaborate than his defensive one – which worked quite well, considering City’s few chances – and played into Guardiola’s hand, as it favored City’s objective to dominate possession. When recovered possession, United would immediately make a diagonal switch to the wingers and try to transition quickly, relying on the player’s 1v1 abilities and speed to reach the opposing goal. Though, United’s close proximity of players after having regained possession, due to the nature of their deep block, rather compact vertically and horizontally, allowed City to counterpress effectively, soon forcing United into helpless long-balls to the forwards (especially Lukaku, often in numerical inferiority), allowing City to recover possession and extend their phases of prolonged control.

Following City’s 1st goal, Mourinho swapped Martial and Rashord’s positions and United started to press higher; United’s pressing was quite uncoordinated as the midfielders – Matic in particular – and the centre-backs rarely supported the press and sat deep which reduced the pressing’s effectiveness and stretched their lines, thus exposing themselves to counters. Still, the Red Devils managed to find the back of net in injury time, mostly thanks to Otamendi and Delph’s individual mistakes.

Second half

The second half saw Gundogan replace an injured Kompany and take Fernandinho’s place at the bottom of City’s midfield triangle, with the Brazilian being moved to centre-back. Guardiola justified this switch by saying that “he tried to make a better build-up”, however the move didn’t quite go as well as the Catalan manager hoped as he was forced to bring Mangala on for Gabriel Jesus, advancing Fernandinho back to DM and Gundogan to CM; these changes caused a domino effect which resulted in Sterling moving to the left wing and Silva as a false 9. Mourinho made a change too: Lindelof for Rojo.

The general patterns didn’t change and the second half was quite similar to the first, with City in control and United looking to dispatch and counter.

Conclusion

Manchester City, showed, yet again, their willingness to dominate possession and drive the rhythm of the game. An often overlooked aspect of Guardiola’s philosophy is to maintain possession as a defensive strategy, and against United he demonstrated it once again. Rarely did the Citizens have to defend off the ball, as they kept 65% of the possession and gave United very few chances of scoring.

Mourinho on the other hand, displayed all the pros and cons of his reactive football. Whilst he almost nullified City’s actions in the final third, he failed to trouble City’s defence.

As Guardiola said in the post match press conference “Football is unpredictable” as City scored two goals in the most uncharacteristic way possible.

City won their 14th game in a row, a Premier League record, ending Manchester United’s 40 matches unbeaten run at the Old Trafford and stretching the gap from their leading spot to second place by 11 points. The League is definitely not won yet – it’s still December – but this is a very good advantage to have, especially considering the way City have managed it.

Pep Guardiola is doing it in England and he’s proving time and time again that he’s still the best in the business.

Writer: Kareem Bianchi/@lAllegrista

Photo Credit: AP