Zach Lowy and Chris Sweeney Discuss “Mad Dog Gravesen”

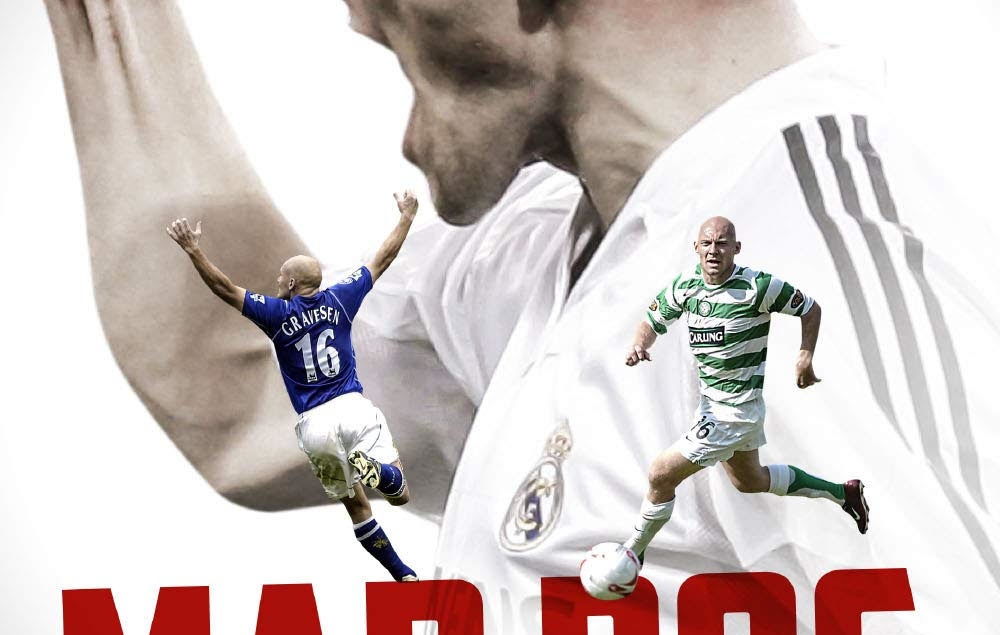

On Friday, February 15, Chris Sweeney’s second book “Mad Dog Gravesen: The Last of the Modern Footballing Mavericks,” detailing the life and career of ex-Real Madrid midfielder Thomas Gravesen, will be available for purchase. Zach Lowy, co-creator of Breaking The Lines, chats to Sweeney about Gravesen’s pranks, his “Mad Dog” nickname, and how he accrued a net worth of €100 million.

ZL: Why does Gravesen have the nickname “Mad Dog?”

CS: He got it at Everton, when he was christened the Mad Dog, but it’s out of love and affection. He’s just a bit of a spontaneous character, he does things how he sees, he doesn’t think about tomorrow, he lives in the moment. Sometimes that’s in his benefit, sometimes maybe not.

One of his teammates at Everton, Alan Stubbs, who was one of his captains at Everton, he described Thomas as the character from Tom Hanks’ “Big.” He was a lovable guy who just lived in the moment.

In Germany, he was called the Humörbombe, I don’t quite know how that translates into English. He played at Hamburg before he came to Everton, and for his actions on and off the field, he was just a lovable guy, very spontaneous, and that’s how he got those nicknames. He was basically a cult hero to those fans.

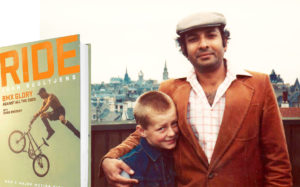

ZL: After writing a previous book about John Buultjens, why did you decide to write on Thomas Gravesen?

CS: Even the book about John that I wrote before this, that’s about BMX and I know nothing about BMX, so it was more about him having an interesting life. Similar to Thomas, I am a big football fun. I started to hear a few things about him and some things that he’d done, and things he’d be involved in. I didn’t know these things, and I thought if I didn’t know them, other people might know them.

As I started to do a bit of research, I started to find out there was a more stuff that I didn’t know, that he had this whole other persona away from football, away from the pitch, that made him stand out, and that’s why I say he’s the last of the modern footballing mavericks. There aren’t footballers like this anymore, they just don’t make it through to the professional game, and they certainly don’t make it through to the top level at clubs like he did.

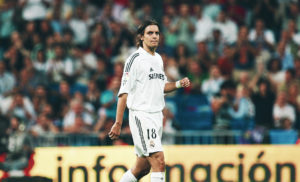

Going to Real Madrid in that Galáctico era, you could never find a loose cannon like that nowadays making it to that level of football, it just wouldn’t happen. I was attracted for a few of those reasons, but mainly for the guy he is, not so much he was a footballer, he just happened to be a footballer.

ZL: By modern mavericks, are you placing the likes of Roy Keane in that list alongside Gravesen?

CS: I actually mentioned Roy Keane in the book, partly competing, him as a maverick. I would say guys like Paul Gascoigne, Eric Cantona, Faustino Asprilla, Matt Le Tissier, Romário, these guys are the modern footballing mavericks. At the back of the book I go through seven or eight mavericks. The word “maverick,” in my understanding of it, particularly when I was growing up, it was always meant to be a player who didn’t full the potential or didn’t do well, and I think that’s not really the case.

I think these guys have done well, and Thomas is an example of someone who did well; you don’t go to Real Madrid if you’re rubbish. You mentioned Roy Keane there, Roy Keane was the captain of the most successful English team for how many decades?

I also wanted to give a different meaning to the word “maverick.” It’s not about these guys that had so much talent and blew it all, it’s a bit more than that. They’re unique individuals, and that’s why they stand out in the game, and I think now there’s very few of them left.

ZL: What do you think explains the extinction of the modern footballing maverick?

CS: One reason is I think there’s so much money in football now, so much pressure that players are now signing for clubs at 8, 9, 10 years old. There’s millions of pounds changing hands for basically children. Sometimes the family has moved over, the parents are given a job in a new country, a new city, to attract this young prodigy. Even now, the English FA have actually put in rules: I think transfer fees start at about 10 years old, and if you take a player, there’s so much you have to pay.

It’s all these complicated things, and you have these academies now. I’m from Glasgow, and Celtic, one of Thomas’ old teams, they have a school where the boys get up in the morning, they have a breakfast, they train, they go to the special school that Celtic run, and then they go to training again. They’re living like professional footballers, and they’re still children.

This academy system of molding people into being athletes and having them like that, what happens is, yes, you might get a lot of good players and you may get a lot of professional, good athletes, but I think you might start to, anyone who’s a little bit different, who has trouble conforming to that then starts to be pushed out.

Thomas is a guy who came from the countryside, a very rural place, and he liked home, and I don’t think he would’ve thrived in that. You mentioned Roy Keane, Roy Keane comes from a middle-of-nowhere island, he doesn’t come from a big place. I think certain characters wouldn’t get through this academy.

Maybe they’re not boring, but they certainly come over to normal people as boring. People nowadays don’t relate to footballers as the same way they used to. They seem to be so sanitized, and whether it’s their fault, whether they’re brought up that way, or whether that’s just how life goes, I don’t know, but I think that’s why you don’t get mavericks anymore.

ZL: A lot of people, when the name Thomas Gravesen comes to mind, they think of certain Real Madrid flops like Jonathan Woodgate that were head-scratching and didn’t quite pan out, but like you said, you wouldn’t give him that designation of “failed talent. What are certain things you think people would be shocked to find out when reading this book?

CS: Jonathan Woodgate, it’s good you brought him up, I think he was a bit of a disaster at Real Madrid. He didn’t make his mark, but Thomas was there for 18 months, and in the big games, he played. The other players talked about him and said he made an impact. You don’t play in a team like that and train with guys like Zidane, Beckham, Figo, Ronaldo, Roberto Carlos; if you can’t play, it would be obvious.

He wasn’t out of his depth and all the players say that. I think that’s become a tag that I don’t know why people think that. Maybe it’s because he wasn’t the typical footballer, and some of the things he did at Hamburg, he brought dynamite into training, he told his friend that it was special fireworks, and he got his friend to light them, and he said, “when you light them, make sure you run.” So he ran, and then obviously, the dynamite exploded and left this big crater.

When he first moves to Hamburg, he misses home, so he buys a motorbike, and he goes about so many hundred of miles* every day. He sneaks back to Denmark, so he’s leaving training in Hamburg, getting on this motorbike, riding like a bat out of hell to get back to Denmark, to spend the night in Denmark, to get up in the morning, to ride like a bat out of hell back to Hamburg. The club didn’t realize, but after a while, when they realized, they said to him, “no, no, no, you can’t be doing this, this is not acceptable.”

He’s a very open guy, he’s a lovable guy. When he went to Hamburg, he wanted to interact with the team and the city. In his apartment, he wrote “Gravesen–HSV,” which is obviously the abbreviation for Hamburg, on his buzzer. So if you were passing in the street and you wanted to chat about the game and you were curious, you could just ring his bell. How many footballers would do that? You’d be lucky to get a footballer giving you out their Facebook page, never mind putting their name on their buzzer.

He did loads of stuff, he used to bring a firebox into training. He would also want to have a slightly lesser car in the winter, so he would have nice cars, but he would sell them and buy second-hand bangers, especially in England, because he didn’t live driving a nice car in the weather when it was raining. He thought, ‘there’s no point in having a nice car, so I’ll sell my car and I’ll buy a really cheap banger, and I’ll drive around in that, and then when the sun comes out, I’ll start buying a Porsche or whatever it was.”

There was one time at Celtic where the manager was doing a team talk, and he’s very passionate about this team talk, and he’s getting right into it, and one of the players looks around and hears Thomas sitting in the dressing room, with a newspaper with the eyes cut out, looking through it, listening to the team talk. He was just cut from a different cloth, just totally, totally different.

ZL: For the youngsters out here, what is one player in modern football who you would compare Gravesen to?

CS: I think off the field there isn’t, and that’s why it’s the last of the modern mavericks. I don’t think there is anyone like him anymore. I think you’d be struggling to find a player who has a colorful life off the field, and he doesn’t do it for headlines, it’s just the way he was.

One of the players at Celtic said to him, “What are you doing for your summer holidays? Where are you going?” He said, “I’m going back to Denmark.” And the guy said, “All right, how come?” He said, “Well, I like to go back and go to my parents’ basement and play video games all summer.” And the guy thought he was joking, and that’s what he was doing.

At this point, he’s very wealthy, he’s going out, he’s dating a very famous Danish porn star, and this is what he’s doing in his summer home, he’s going back to sit in his parents’ basement to play video games. He really did what he wanted to do, and I don’t think there’s any players that I can think of that do that.

In terms of his on-the-field thing, I think there are players who probably resemble him on the field. He was a combative midfielder with skill, I’m trying to think who’d be a good example, maybe Xabi Alonso? Maybe someone like that might have had shades of Thomas Gravesen, but he was a bit of an all-rounder. He was quite good with the ball, he could dribble, he could tackle, he was a good all-rounder, and I think that’s what made him a good player. He was able to do quite a fair bit of everything.

Maybe a bit like Wayne Rooney in some ways, that kind of good, all-around player. He could play in different positions and not look too out of place because he was too good.

ZL: So he went from the Danish porn star to the Czech model, is that correct?

CS: He split up with the Danish porn star, and then he disappeared off the face of the Earth. He left Celtic, and he just disappeared off the face of the Earth. He reappeared three years later, living in Las Vegas in a gated community with Nicholas Cage, Andre Agassi, and Penn Jillette from the Penn & Teller magic duo. They were his neighbors, and he was dating this Czech-American woman.

I don’t know if she was totally a model, that’s been said, I think she may have done a bit of modeling but I think she’s also a real estate agent as well. I don’t know if she was like a big-time model; his porn star girlfriend was very famous, but I don’t know if his girlfriend that became a model was well-known. They’ve now split up, so he’s no longer with her anyways.

ZL: And the £40 million that is saved up in his bank account, what is that exactly from?

CS: It’s a lot more than 40 million, it’s rumored to be about 100 million. If you can find out who first discovered that, you’re a better man than me. It’s all over the Internet but Thomas never said, “I made this money or I got this money from that,” so there’s a number of theories.

One is that he became a great card player, and obviously a bit of money from the football, so he was able to use that and go into cards and become an expert.

Another theory was that he invested in casinos and hotels and that took off, and another theory is that he just became so good at business, he just got into business and put money into some companies and it paid off for him. But there’s no actual proof from him, he’s very very private, he has no social media, he has no websites, if you go on YouTube, you’ll have a hard time of getting a video of him actually talking, and especially in English, I don’t think there’s anything on YouTube of him speaking English, although he can speak English.

My opinion is he probably does have the money because he clearly has a nice lifestyle. The way he was living in America wasn’t cheap, it was many, many millions. He’s bought quite a big bit of land back in Denmark that he was going to re-develop, but that didn’t work out for legal issues out of his control.

There’s no real reason, I mean, one of the things in the book is there’s someone who saw him, and whether you believe this person or not, saw him lose $54 million in a game of one-on-one poker in a high-stakes Las Vegas room. And you would say “Oh that’s a lot of rubbish,” but why is the person going to say it? There’s no reason for this person to like…Thomas Gravesen is not some well-known person in the Las Vegas poker scene, this person just put it out there.

Like I say with Thomas, that’s part of the mystery. You go on wikipedia now and you can know everything about footballers. You can know what they had for lunch because they put it on their social media, whereas with him, there’s a lot of ifs, buts, and maybes, and I think that’s also part of the attraction. For me it was, anyways.

ZL: Gravesen’s perhaps the biggest prankster that modern football has known. We’ve got the fireworks, the tea-bagging of a Danish teammate, the fights with Robinho and Ronaldo while he was at Real Madrid. Was there any evolution in his pranking career and what do you think explains the quantity and the ridiculousness of his pranking?

CS: You see, I don’t think he saw it like that, I think he just thought, “I’m going to have a laugh here, I’m going to have fun.” Apart from the Robinho thing, that was violent, but I think him and Robinho had a bit of a clash.

He did have a short temper. When he was younger, he was taught a trick by his mentor, where he would have three imaginary stones in one hand, and he would transfer them to his other hand mentally, and that was to give him a bit of time to calm down and relax.

I wouldn’t say he was bad-meaning with his pranks, I just think there was more of a sense of, ‘he shouldn’t do that.’ He would just do whatever he thought was the right thing to do.

With Ronaldo, he ends up knocking Ronaldo’s teeth out, which I’m sure Real Madrid’s manager wasn’t too happy that their Brazilian superstar was on the floor here getting mauled by this crazy Danish guy, and he ends up knocking his teeth out.

He would do things like that, but I think it was all in good humor. I don’t think he was trying to be difficult.

He went through a period at Celtic where he loved Batman, the Batman movies, so he took the whole reserve team to see Batman because he’d been banished from the first team because the manager wasn’t seeing eye-to-eye with him. He went on this trip to Ireland, which was really beneath his level, and it’s a credit to him that he went, because he had a great attitude, he goes there, he’s trying really hard, and he takes them all out to see Batman. For the rest of the trip, on the pitch at training, he pretended to be the Joker.

He did loads of things. At Hamburg, he broke into their wellness center, filled all the baths with bubble bath products, and he’s made this bubble bath infinity pool, and he’s sliding about naked with his friend along it.

They did so much. Like I said, he would have a problem with training. He didn’t like people shouting at him when he was shooting. So he got to this point at Celtic where he’d stop the ball and say, “Don’t shout at the shooter, I hate that! When I’m shooting, don’t shout!” When you play in front of 50, 60 thousand people, what the hell difference does it make?

I don’t think he was trying to be difficult, I just think it was the way he was. If he thought something was funny, he did it.

ZL: I know there’s one story of him during an Old Firm match, asking Barry Ferguson, “Are there any good places to eat in Glasgow?”

CS: Exactly, you can imagine an Old Firm game, Celtic and Rangers, deadly rivals, and here’s the captain of Rangers, their best player as well at the time, coming off at halftime, and this Danish guy comes up to him and says, “Excuse me mate, do you know any good restaurants to go for dinner?” I think he thought he was crazy, but he was serious. That was just “we’re going in for halftime, I want something to eat tonight, I’ll ask this guy because he’s from Glasgow, he’ll probably know a good place.”

I don’t think he was trying to be funny. That same game, the manager says to him, “Right Thomas, today I need you to focus. You’ve got to play well, I don’t want you talking to the referee, don’t shout at the referee, I don’t want you getting any yellow cards, just mind your own business.”

They’re getting ready for the game, and there’s a knock at the door about 10 minutes before the game’s about to start, and it’s the referee wanting to check the books. Of course who opens the door? Thomas Gravesen, and he looks at the referee, and he just says, “Sorry lad, I’m not allowed to talk to you today,” and slams the door in his face.

That’s just the way he was, he was just spontaneous.

ZL: Would you say that Gravesen succeeded because of his unique personality, or in spite of it?

CS: That’s an interesting question. I think at different stages of his career, I think it helped him, and I think at other points it didn’t help him. I think when he was starting out, he was very determined.

One thing that most people talk about is that he was very obsessive with stuff. He got really into pool, so he’d come to Celtic every day with his pool cue. He’d train, and then go play pool. Then he became really into Call of Duty, he got really into cars.

There were things that he got into that he became almost obsessed with, like the Batman thing, he took it so far that he was impersonating the Joker. He would get really into things quite deeply.

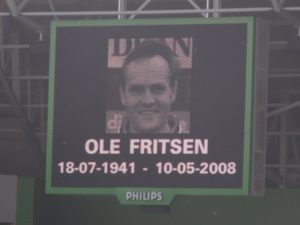

I think at the start of his career I think that helped, because obviously, practice, practice, practice, repetition, that developed his skills. But I think when he had someone, back home at Denmark he had a guy called Ole Fritsen, who was his mentor, and he was able to get through to Thomas. And when I say “get through,” I don’t mean he let him do what he wanted, but he understood this guy’s not your run-of-the-mill guy, you’ve got to give him a wee bit of latitude to be the person he is so that he can play football at the level I know he can.

When he was at Vejle, which is the club at Denmark he started at, he felt like after training he had nothing to do. So he took a job in a car parts shop, selling car parts. And you think to yourself, ‘You’re on the cusp of going to the major European leagues, you’re obviously a very talented young footballer, what the hell are you doing going and working in a car parts shop?’ He was that kind of guy.

ZL: And it wasn’t about money, it was just about doing something else to mix it up.

CS: It was just, “I’ve got spare time on my hands, so let’s do that. I’ve got spare times on my hands, that sounds like a good idea, so I’d quite enjoy that.”

When he goes to Hamburg, he doesn’t have that connection. The manager can’t quite get around it, and at Everton he has it again, at Celtic and Real Madrid he didn’t. I think at certain points it helped him, at certain points it held him back.

The game of football, as it became more modern and more professional or sanitized or however you want to see it, there was less freedom for people to act out of character from what a “footballer” should be. I think ultimately, it made Thomas fall out of love with football, because at 32, you can still play. Two years after playing at Real Madrid, he quits football and disappears off to be never seen again for three years, until he appears in Las Vegas.

Clearly something happened. He just must’ve fallen out of love with football, and I think that’s a shame. His character, at different times, helped him and didn’t help him, depending who was on the other side of the table in terms of being his manager.

ZL: What’s one thing you want people to take away from “Mad Dog Gravesen?”

CS: Well I say it on the first page, it’s a message to Thomas: be yourself. He was his self, and good on him. He didn’t change, he didn’t feel like, “I better be quiet, I better not be this guy because I’ve got to be something that people expect me to be.”

He was his self, and he achieved that at a good level. When anyone says “Thomas Gravesen’s a failure,” I feel like saying, ” I feel like saying, well, “Did you play for Real Madrid? Did you go to the World Cup? Have you played for Everton in the Premiership in front of so many thousands of people? Have you made millions from football? No, so, shut up.”

If I was his father, I’d think, “Yeah, you did pretty well.” I’d like people to take that thing of ‘be yourself,’ and also be accepting of people. A lot of times, Thomas was referred to as a lunatic, a screwball, mental, and some of these terms, we all use certain ways, but if you’re the person and someone’s calling you crazy, a lunatic, a screwball, maybe if you’re a certain person, maybe you start to think, “Is there something wrong with me?” Especially kids.

I do call the book “Mad Dog” because that was his nickname, but it was affectionate. I hope people take from the book, number one, be themselves, and number two, be understanding of other people, we’re not all the same.

I think that has to be celebrated, particularly in sport, where you want to see characters out there, it isn’t life or death, it’s entertainment. Let’s do it with a smile on our faces.

*(According to routeyou.com, which calculates transportation distance for motorcyclists, the distance between Hamburg, Germany, and Vejle, Denmark is 305 kilometers, or 190 miles. As such, Gravesen would have commuted a total of 380 miles per day between his training sessions in Hamburg and his home in Vejle).

Buy “Mad Dog Gravesen” today: https://www.pitchpublishing.co.uk/shop/mad-dog-gravesen