A Betzenberg Story: Kaiserslautern’s Imprint on the Beautiful Game

The annals of football history are strewn with tales of yesteryear. Be it former stars, clubs that once held a continent at their fingertips, and nations who otherwise seemed destined for greatness, looking back as a way of also looking forward is commonplace among professional sport. Football is no different. But so often, the influence of those that came before goes overlooked.

Few, if any, that are mad about the beautiful game can deny the influence that perennial powerhouse Germany, and the Bundesliga, have held for decades in the post-World War II era. Only Brazil have lifted the World Cup more times than Die Mannschaft, while Germany can not only boast the joint-most European Championship honors along with fellow continental powerhouse Spain, the nation has also seen Bayern Munich become club footballing royalty on the back of six Champions League trophy hauls as the flagship enterprise on the domestic front.

For the first time in 21 years, Kaiserslautern are headed to the DFB-Pokal Final!

After beating Rot-Weiß Koblenz, Köln, Nürnberg, Hertha Berlin and Saarbrücken, they have booked their spot in the final on May 25, where they will play Bayer Leverkusen or Fortuna Düsseldorf. pic.twitter.com/VmLmgi2RFJ

— Breaking The Lines (@BTLvid) April 2, 2024

But what history tells us, if you listen very carefully, is that such dominance likely would not have been possible without a storied institution that has, unfortunately, well and truly fallen by the wayside; 1. Fußball-Club Kaiserslautern e.V. To understand the impact that Die roten Teufel have truly had on football, one must go back to the Wankdorfstadion in Bern, Switzerland during the 1954 World Cup.

Germany, still in the midst of recovery in the aftermath of the Second World War, found itself in the final and opposite of what was the footballing powerhouse of the day; Hungary’s Golden Team, the Mighty Magyar’s. Sepp Herberger’s Vertragsspieler against a Hungary side chock-full of professionals.

Brilliant players the likes of Puskás, Kocsis, Bozsik, and Czibor, who at the time were at the tip of the footballing spear in Europe, would never again achieve international greatness, while goalkeeper Gyula Grosics is reported to have felt their failure to win helped sow the seeds of domestic uprising two years later. In the aftermath of Bern, Puskás would go on to Real Madrid CF, while Kocsis and Czibor would also land in Spain, heading to FC Barcelona.

What had transpired across 90 minutes in front of 62,500 spectators would eventually be dubbed Das Wunder von Bern, with Germany storming back from an early two-goal deficit inside the first ten minutes to lift the nations’ first-ever Jules Rimet Trophy thanks to a strike from 1. FC Nürnberg legend Max Morlock and a brace by Der Boss, Helmut Rahn.

After a comprehensive 1-0 defeat against Holstein Kiel – their third defeat in four matches – 7-time Bundesliga champions Schalke are at risk of dropping down to the third tier for the first time ever, sitting two points above the drop.@shaunconnolly85:https://t.co/311Vyx9DkQ pic.twitter.com/gvhRAZJnTT

— Breaking The Lines (@BTLvid) February 12, 2024

Victory over a Hungarian side that had not tasted defeat in four years (over thirty matches played) not only kick-started Germany on to economic, political, and sporting progression, but caused a reversal of fortunes for a nation in Hungary that would never again reach the same heights despite their most recent revitalization under Marco Rossi.

But this is not a tale of Hungarian yesteryear. Rather, it is a celebration of the influence of Kaiserslautern and its vital role in lighting a fire under an entire nation. German champions in 1951 and then again in 1953, Lautern players formed the nucleus of the nation’s triumph in ’54. The legendary Fritz Walter (captain), younger brother Ottmar, Horst Eckel, Werner Kohlmeyer, and Werner Liebrich, all featured in Herberger’s XI in the final.

Though Eckel hailed from the small town of Vogelbach situated roughly 30km outside of Kaiserslautern, the brothers Walter, Kohlmeyer, and Liebrich were all native sons, and their impact on football extended not only to Germany’s win in 1954, but to 1FCK.

When it was all said and done for the local quintet, four – excluding Kohlmeyer, as no data could be found – logged 1146 club appearances while amassing 741 goals, though it stands to note that 682 of those goals were courtesy of Fritz and Ottmar respectively.

Bayer Leverkusen sat five points clear atop the Bundesliga with three matches left in the 2001/02 season and looked on course for a treble — they would proceed to lose the league to Dortmund by a point and finish trophyless.@HE_Ftbl on ‘Neverkusen’:https://t.co/xKrRwjwBA0 pic.twitter.com/GJQUEvg1lj

— Breaking The Lines (@BTLvid) February 7, 2023

Football is, however, a funny old game after all though, and strangely enough, Kaiserslautern-influenced success for the national team did not translate to fortunes at club level for the Rhineland-Palatinate outfit. Despite the triumphal marches in the league during the 1951 and 1953 seasons, and ominous 5-1 drubbing by Hannover 96 in the now-defunct German Championship final pre-dated just the 1954 World Cup by only a matter of weeks.

Even though the club won the Oberliga Südwest, which led to their qualification to the championship tournament, the loss against Hannover left a dark cloud over the Betzenberg, and a similar fate befell them just a year later in 1955, when tasting defeat in the German Championship final once more. This time, a 4-3 courtesy of Rott-Weiss Essen.

In the wake of their successful 1953 campaign, despite their sons’ World Cup heroics in Switzerland, 1FCK would not lift a trophy – league or cup – until their 3-2 DFB-Pokal win against SV Werder Bremen during the 1989-90 campaign. Though the club reached a number of cup finals from 1960-80, a barren patch plagued one of Germany’s most famous clubs.

DFB-Pokal success was immediately followed by Bundesliga triumph a year later, along with top-five league finishes in three of the following four seasons. And though another Pokal win would come in 1995-96, constituting a considerable trophy haul across a relatively short span, so too did relegation.

Hertha Berlin have spent €178.2m on transfer fees since the summer of 2019, whilst their crosstown rivals Union Berlin have spent €66.7m in that same period.

Union will be playing Champions League football next season, whilst Hertha will be playing in Germany’s second tier. pic.twitter.com/2kjZAQ0FII

— Breaking The Lines (@BTLvid) July 7, 2023

A quick return to the German top-flight would ensue, however, after Kaiserslautern topped the 2. Bundesliga table. What happened afterwards would be another historic feather in their cap. Under the stewardship of former Bayern manager Otto Rehhagel, who was sacked by the Bavarian giants the previous year, 1FCK became the first and only newly-promoted club to lift the Bundesliga trophy in the competition’s history.

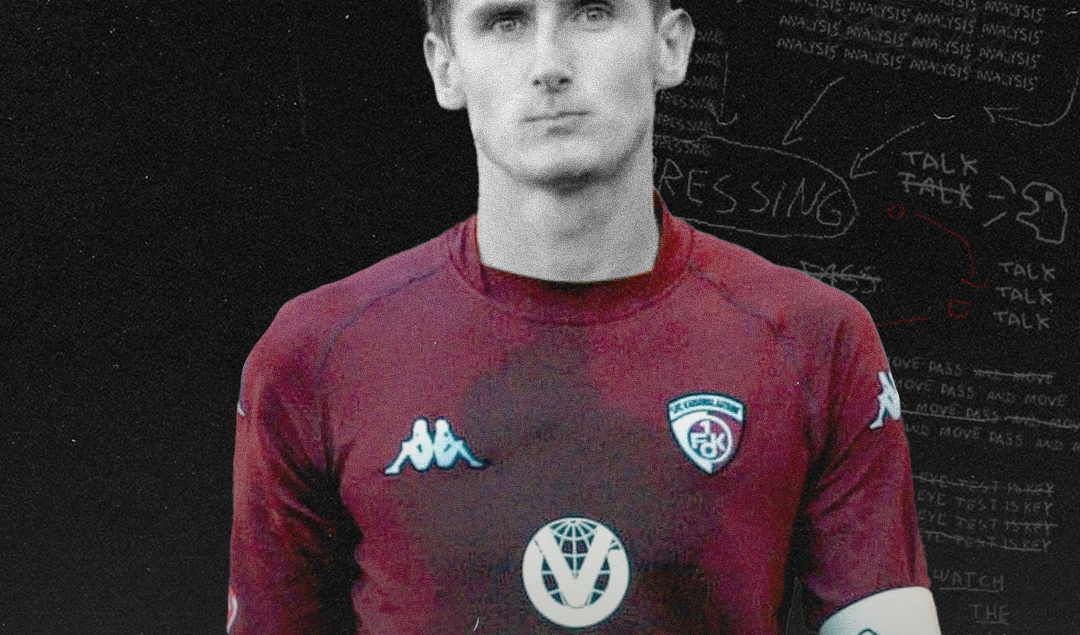

Rehhagel presided over a side that featured the likes of the aged-yet-great Andreas Brehme, talisman Olaf Marschall, and Czech stalwarts Miroslav Kadlec and Pavel Kuka. Together, with notable Bulgarian international Marian Hristov, Swiss midfielder maestro Ciriaco Sforza, and a young prodigious talent by the name of Michael Ballack, 1FCK wrote their name into the history books.

Unfortunately for an elated and devoted fanbase, it would be the last time the Betzenberg would bear witness to any notable footballing success. What would follow was a period of considerable inconsistency in terms of league standing; down, then up, and then back down again. Relegation in 2005-06, redemption in 2019-10, and then failure to avoid the drop once more in 2011-12, which would be the last time one of Germany’s most storied clubs would ever grace it’s top-flight competition.

Lautern would languish in the 2. Bundesliga for six years, including three seasons where top-three and top-four finishes would get them close to a return, but not close enough. At the completion of the 2017-18 season, and with an 18th-place finish in the table, Kaiserslautern were relegated to the 3.Liga for the first time in it’s history, all but sealing the club’s unfortunate fate.

Bayern Munich are on track to miss out on the Bundesliga title for the first time in 12 years, with the Bavarian giants trailing Bayer Leverkusen by eight points with just 11 games remaining.@stzysultan takes a look at the roots of Bayern’s decay:https://t.co/ijUiwls7pr pic.twitter.com/FJhAobrKKj

— Breaking The Lines (@BTLvid) March 1, 2024

Upon Germany sealing its credentials as host of the 2006 World Cup, Kaiserslautern was chosen as one of the ten venues across the country. As a small city in a region of Germany that could only boast a historically modest financial picture, this was viewed as a potential boon to the local economy.

As such, the Fritz-Walter-Stadion underwent major renovations from 2002-05, which also included expanding the grounds capacity from 38,500, to 49,850. While most cities that were chosen as venues benefitted in the long term, Kaiserslautern’s forturnes, once again, saw them worse for ware.

Initially, this was not an issue, provided the club remained in the top-flight of German football. But when they failed to avoid relegation in the 2005-06 campaign, stadium expenses reared their ugly head. In conjunction with relegation, promotion, and then relegation again over the course of six seasons, 1FCK spent well over their financial means in a bid to quickly get back into the league and hopefully stay there.

The result would be multiple instances of stadium rent in need of financial restructuring by the club with the help of the local government. But as club revenue decreased, along with failure at board level to keep spending at a sustainable level, relegation to the third tier sapped Kaiserslautern of any cash reserves that remained as a life vest.

Once upon a time, Gladbach were more than just a thorn in the side of the Bavarians — they were a team that won five league titles between 1969/70 and 1976/77 and reached four European finals in that same time span.@HE_Ftbl on Gladbach’s glory days:https://t.co/m9GBNNRETs pic.twitter.com/M9wNvSisKF

— Breaking The Lines (@BTLvid) September 1, 2023

Rumoured outside investment in 2018 was linked with interest in not only the club, but area development around the Fritz-Walter as well as in the Rheinland-Palatinate region at large, but ultimately would never materialize. Debts of up to twenty million euros were touted as of four years ago, and the club having no way to cover without serious outside investment. As a result, Kaiserslautern ultimately filed for bankruptcy and were declared insolvent.

The club, however, are one of a multitude of German clubs who had suffered financially in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, which included 13 of the 36 combined teams in Germany’s top-two footballing tiers. At the time of writing, Kaiserslautern sit fourteenth in the 2. Bundesliga table and still at risk of facing another relegation down to 3.Liga just two years removed from clawing their way out of the basement.

Hope could very well be just on the other side of the Betze, however, after the club managed to reach DFB-Pokal final (a first in over twenty years) and a stern test against Xabi Alonso’s record-breaking Bayer Leverkusen outfit at the Olympiastadion in Berlin.

Still, there is no telling what the future holds for the Pfälzerwald-club, but certainly, there is a risk that their historic footprint remains but a distant memory. However, it cannot be understated at just what this club has meant to the locals, a nation, and the cadre of players that have stopped at the Betzenberg along their way.

It has been four months since Stuttgart narrowly avoided the drop for a second straight year after beating HSV in the relegation play-off.

Today, they sit second in the Bundesliga thanks in large part to Serhou Guirassy’s red-hot form.@shaunconnolly85: https://t.co/0XHEaF7qbs pic.twitter.com/8lLjp7uN1Y

— Breaking The Lines (@BTLvid) October 20, 2023

Added to the aforementioned list of former stars, the likes of Miroslav Klose, Youri Djorkaeff, Willi Orbán, Mario Basler, Stefan Kuntz, and Klaus Toppmöller can all count themselves as former Red Devils. But why would an American from New York City choose to pay homage to a club that most of my countrymen and women have likely ever heard of? Well, I have my childhood to thank for that.

Growing up in the Riverdale section of the Bronx, a neighborhood firmly rooted with a German and Eastern European community, my childhood best friend was a second-generation American of German descent. When I began playing football at the age of six, Robbie and I started together at youth level. Though I would go on to play to a relatively high level, including being recruited collegiately, Robbie stopped playing at a much younger age. Despite that, it was his Opa that played a huge role in fostering my love of the game since childhood.

Opa was a massive Kaiserslautern supporter. And though his life was placed into unparalleled upheaval, including being sent to concentration camps, football remained a constant in his life, and he was lucky enough, along with Opa, to see Fritz Walter play live, and in color. Despite my first football top being a Bayern jersey (it was a gift, so please do not judge), he would always show them great respect. But nothing made his face light up more than talking about Lautern.

As I have both read and covered news in recent years revolving around 1FCK’s constant financial struggles, and consequently, their bankruptcy, it was a tough pill to swallow. Without them, it can certainly be postulated that Germany would have never come into the fold as one of the world’s leading footballing nations, let alone manufacture economic and social rebirth from the ashes of unfathomable conflict and human tragedy.

FC St. Pauli have announced that they will no longer deal with football agents for their academy players, in order to take a stand against the commercialization of youth football.@tomshelton11 on what makes St. Pauli more than just a football club:https://t.co/It9jhpJJTM pic.twitter.com/XY2re52gok

— Breaking The Lines (@BTLvid) September 28, 2023

So, to all those who live and breathe Kaiserslautern, and who continue to experience the ground that bears the name of the city’s most famous son in the hopes of returning to dizzying heights in the future; here’s hoping lady luck shines bright on top of the Betze once more. Football – and Germany – would never be the same without you.

Schlaf gut und süße Träume, Opa…

By: Andrew Thompson / @GeecheeKid

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / Sandra Behne / Bongarts