“Are We Stronger Together Than Apart?” – The Nearly History of Wimbledon Rangers

It’s the dawn of a new era at Loftus Road. In the next few minutes, the navy and white-hooped Wimbledon Rangers will kick off the first game in their history. The club is desperate to move on from the summer of controversy and focus on the future and promotion to the Premier League.

Wimbledon Rangers never did kick off. Nor did the Queens Park Dons, the R Dons or the Wimble-Hoops. But they got close enough to thrill two boards and dismay thousands of fans.

QPR and Wimbledon took a while to grace the game’s heights. Each have just the one improbable major trophy: the Crazy Gang’s 1988 FA Cup and the Rs’ 1967 League Cup, won from the Third Division.

Photo: Getty

They’d been fellow top-flight sides for nine years from 1986, embarrassing far bigger clubs with frequent forays into the top half until QPR went down in 1995. Wimbledon followed four years later and fell just short of the play-offs in the 1999-2000 season, their first back in Division One.

QPR’s season had been disastrous. The Dons hammered them 5-0 to trigger a ten-game winless run that would condemn Rangers to third tier football for the first time in thirty-four years.

It was after that Selhurst Park rout that the idea of a merger was first raised, although QPR director Nick Blackburn claimed it was discussed “half-heartedly” and was a “bit of a joke.” They weren’t laughing for long. The QPR board were soon working up proposals and a formal approach was made to Wimbledon.

The logic was clear. QPR were dead broke with a stadium of their own while Wimbledon were solvent-ish but homeless. Charles Koppell, a man who’d never been to a football match before becoming Wimbledon’s chairman, breathlessly declared: “Both clubs have a unique set of problems and we have to ask, is there a way to resolve those problems? Are we stronger together than apart?”

Photo: Getty

The recently-founded supporters trust QPR 1st lobbied hard against the proposal, while still admitting that it was “a good business proposition.”

Pop mogul Chris Wright had bought QPR in 1996 with a fortune built on Blondie, Jethro Tull and Spandau Ballet. It was going to be gold; lifelong fans would come to the rescue and carry his club back to the Premier League.

Five years on, with millions wasted and supporters’ goodwill spent, QPR were in administration and bound for Division Two. Wright the businessman saw a deal that would secure the club a future of sorts and give him a way out. But Wright the fan feared notoriety as the villain responsible for his club’s disappearance, shown in his anxiety about there being enough of QPR’s name in the new club’s. It left him conflicted, willing to support the talks but never quite convinced.

Mergers were common in early English football history; QPR themselves were formed when St Jude’s Institute and Christchurch Rangers came together in 1886.

Photo: The Football Archive

More recently, there had been a steady trickle in the non-league but it had been many years since a merger at the higher levels of the game. The plotters believed that the clubs’ parlous situations and their lack of enmity gave them a chance.

There was not the instinctive antagonism of previous ill-fated proposals involving QPR, Brentford and Fulham or Wimbledon and Crystal Place. It had only been fifteen years since the two teams first met competitively and both had rivals closer to home.

On May 3rd 2000, after a couple of months of secret discussions, The Sun got the scoop. Loftus Road PLC, QPR’s holding company, grumbled that it was “not helpful that the news has been leaked as we were intent on exploring the opportunity in a sensible and controlled manner.”

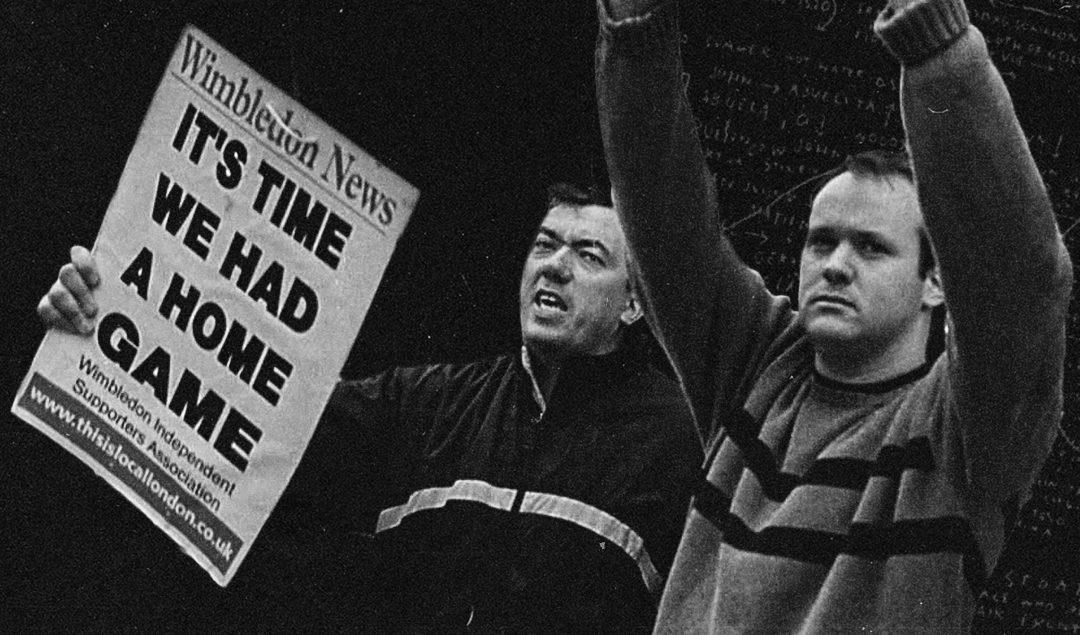

The Wimbledon Independent Supporters’ Association declared that they would “unequivocally oppose the merger of two separate identities, families, supporters and histories.” QPR 1st promised to “fight tooth and nail to protect” QPR. The QPR Board promised there would be a vote.

Photo: QPR Report

Blackburn asked whether QPR fans wouldn’t rather watch a team “wearing hoops” (possibly with Wimbledon in the name) playing Man City at Loftus Road in front of 20,000, rather than QPR v Bristol City with 8,000. The question showed up the gulf between those in charge and those in the stands.

The Board had identified the kit and the stadium as beloved by the fans so if they could just keep them, everything would be fine, wouldn’t it? They soon realised that these things only matter as part of an identity. As for the appeal of famed opposition, they need only have looked at the clubs’ histories to know that wasn’t what their fans kept coming for.

The Football League doesn’t know what it thinks of mergers. When Robert Maxwell tried to create the Thames Valley Royals, the League praised the pension-thieving crook’s proposals as “bold and imaginative.”

Five years later, when property developer David Bulstrode wanted to turn Craven Cottage into luxury flats, the League opposed Fulham Park Rangers. Another ten years on, the League did not take a stance on Bury, Rochdale and Oldham’s potential join-up but did decide that the new club would have to start in the division of the lowest-placed team.

Photo: Friends of Fulham

This time, they hedged their bets. They promised that while they would “give favourable consideration to any proposal, they must also bear in mind the implications for the league competition and for the supporters of both clubs.”

With growing anxiety about the game’s finances, they had to be seen to fairly consider the proposal. They could, however, see the fans’ response and had no interest in sharing the flack.

Just three days after becoming public, the merger was no more. Football was overshadowed by fan fury at both clubs’ end of season dead rubbers. Amidst heavy booing, Koppell came on the pitch to announce that the plans would go no further. No talk this time of “stronger together.”

Koppell was now keen to stress it had all been QPR’s idea. The QPR board defiantly noted that “the proposal had some financial and theoretical merit” but admitted that “the strength of feeling from supporters to maintain the QPR identity and history was overwhelming.”

Some have suggested this was all part of a masterplan, a cunning ploy from Wright to prompt potential buyers to come forward. As a QPR fan, I’m inclined to discount this theory on the basis that nothing in Wright’s tenure suggested that he was capable of long-term strategising. Cock-up feels a far safer bet than conspiracy.

Photo: Vice

He would later ruefully reflect that “when it comes to football, all similarities to normal business disappear out of the window completely”, showing the bemused frustration of a man who never got it.

What if the boards had faced down the opposition and forged ahead? Given the ingenuity and commitment of Wimbledon fans when their club was eventually taken from them, it seems very likely that AFC Wimbledon would have come into being a year earlier.

There’s a good chance they would have been joined by a QPR phoenix club, although there would likely have been an ugly split between “new clubbers” and Loftus Road loyalists. Perhaps the two new clubs would have built a rivalry as they made their way up the divisions.

If, as Wright claimed, there were many chairmen keen on similar moves, they would have closely followed Wimbledon Rangers’ fortunes.

Had the hybrid club been able to cling onto enough fans to be viable, it might have given others confidence to take the plunge. At the very least, it would have forced the Football League to establish a transparent process for considering mergers.

A few weeks after the merger was abandoned, a man soon to become infamous in Wimbledon’s history was at the Queen Adelaide pub in Shepherds Bush. Peter Winkelman presented to QPR fans on the merits of a move to Milton Keynes. His audience described it as a “shambles.”

Once QPR confirmed their lack of interest, Winkelman returned to Wimbledon who had rejected him a year earlier. Now, however, Koppell was in charge and offered a far friendlier welcome.

By: Andy Ryan

Featured Image: @GabFoligno