The Copa Latina: A False Dawn for Continental Football in Europe

Consciously or unconsciously – we’re always borrowing from the past. We channel Aristotle every time we use deductive reasoning in even the most trivial of arguments. Half of the words on this page come from a single ruff-necked bard and the rest from ancient tribes in continental Europe. The false 9 had been around for 80 years before Pep Guardiola, Total Football is as Austrian and English as it is Dutch, and Cristiano Ronaldo walked so Kylian Mbappé could run – very quickly – at a terrified full-back.

Football is particularly anaemic when it comes to fresh ideas. Almost everything we see has been recycled, repurposed, repackaged from a thought that materialised in someone else’s head. This is not a condemnation; it’s the opposite. Is a J Dilla sample manoeuvre any less beautiful because we know he didn’t create the original sound? Is a Caravaggio any less haunting because he didn’t mix the paints himself? Standing on the shoulders of giants is the name of the game. Only sometimes the giants can’t take the weight.

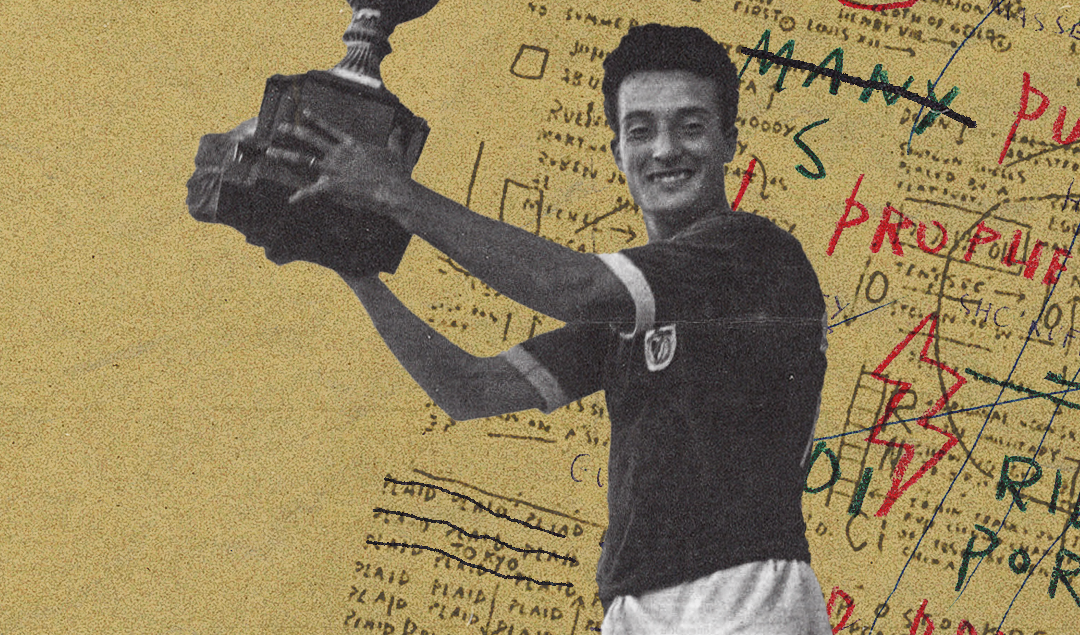

The European Cup’s sophomore season came to a close at the Santiago Bernabéu on 30 May 1957. To rapturous acclaim, Real Madrid won the second of five consecutive titles after a 2-0 victory over Fiorentina. Three weeks later in the same stadium, Real Madrid won another European trophy, beating Benfica by a single goal from Alfredo Di Stéfano. This time, celebrations were decidedly less manic. This was the Copa Latina, the tournament played out by the champions of Spain, Portugal, Italy and France at the end of *nearly* every season between 1949 and 1957.

Photo: Diario AS

Along with the Mitropa Cup (contested by the best teams from central Europe) and the Balkan Cup (contested, unsurprisingly, by the best teams from the Balkans), the Copa Latina served as a dry run for a true continental competition, one that encompassed all of Europe. Logistics, a lack of legislative will, and the Iron Curtain separating the Eastern Bloc from the rest of the continent made such a competition impossible until 1955.

For many years, the Mitropa Cup was the zenith of the club game. But the Second World War halted the 1940 tournament before the final was played, and the Mitropa Cup took place only once between then and 1954. As such, the Copa Latina became the European competition with the most prestige, a status which lasted for nearly a decade.

Around this time, Spain, Portugal, France and Italy were establishing themselves as the strongest forces within the game – illustrated by the fact the first 11 European Cups were won by teams from within the four federations. In those 11 years, only two teams from outside the four countries managed to reach the final, Eintracht Frankfurt in 1960 and Partizan Belgrade in 1966.

For all intents and purposes then, the Copa Latina might as well have been the European Cup, though its setup was less nebulous. There were just four matches each year, two semi-finals, a third-place play-off and a final. Fixtures were decided by the drawing of lots. Each edition was part of a four-year cycle; a silver cup was awarded to the winner of each tournament while a gold one was given to the most successful federation at the end of each series. Spain won the gold cup at the end of both of the Copa Latina’s two cycles.

As travel costs were enormous in the late ’40s/early ’50s, the event was held in one host country each year. Spain, who had been the driving force behind the formation of the competition, hosted the first edition at the end of the 1948-49 season. It began in tragic circumstances, however. The entirety of Torino’s squad along with six members of staff, three journalists and four flight crew were wiped out in an air disaster a little over a month before the tournament was due to start.

Photo: Getty Images

Torino – Italian champions five years running and probably the best team in the world at the time – were forced to take a squad made up of youth players and those that other clubs had loaned them to the inaugural Copa Latina in Spain.

Rather bafflingly, not everyone was content with Torino’s continued presence at the competition. They had been awarded the Italian title with four matches remaining but Maurice Pefferkorn of France Football charged the organisers with “pitting rules against sentiment” in allowing a team of youngsters and hired hands to take their place. “This tournament is sullied by a mistake through the presence of Torino in the competition,” he said in a passage that does not reflect at all well on him or his publication.

The Granata’s hastily assembled patchwork squad were unsewn by Sporting Lisbon. They won 3-1 with Fernando Peyroteo scoring a hat-trick. Peyroteo was a supreme goalscorer, perhaps the best there ever was. His three strikes were indicative of an absolute fixation with the back of the net – he scored 544 times in just 334 career appearances.

With Albano, Jesus Correira, Manuel Vasques and José Travassos, the Angola native formed the forward line known as cinco violinos (the “five violins”) who scored well over 1000 Sporting goals between them. Correira got on the scoresheet in the final, but it wasn’t enough as Barcelona became the first Copa Latina champions – and in Madrid’s stadium too.

There were some grumblings regarding the competition rules in 1949. Goalkeepers were allowed to be taken off in case of injury, but not outfielders. Despite this, a couple of outfield players were withdrawn throughout the course of the tournament – Travassos of Sporting and Macchi of Torino. One commentator declared: “an official competition which does not abide by the rules under which it is played runs the risk of not being taken seriously and to fall to the level of friendly tournaments.”

If credibility is what the organisers sought, the 1950 event did not help their cause. With the World Cup in Brazil clashing with the tournament, Italy and Spain’s would-be Copa Latina representatives were starved of players. France and Portugal did not enter the World Cup in 1950 and their number was not affected. But without the stars from Italy and Spain, the event lost much of its gravitas.

While France Football’s 1949 comments regarding the Italian representatives stunk of hardheartedness, they carried more credibility the following year when they said: “For the second time in two years, Italy distorts the competition.” Juventus had won Serie A in the 1949-50 season, but Lazio represented Italy in that year’s Copa Latina in Portugal despite the fact that they had finished 4th – Juve, Milan and Inter did not have enough available players.

It was, therefore, no surprise to see a Portugal-France final, though it was a surprise to see it take 266 minutes for a winner to emerge. A madcap 3-3 draw saw the match between Benfica – managed by Englishman Ted Hughes – and Bordeaux go to extra-time.

The scores remained level at the end of 120 minutes, and a replay was scheduled. Bordeaux took the lead in the first half of the rematch and led 1-0 going into added time. But Benfica equalised with seconds remaining and sent the match, yet again, to extra-time.

After 120 minutes, the score was still level. With no contingency plan, the referee simply allowed play to continue. The game was nearly two and a half hours old before Julinho da Silva scored the golden goal that won Benfica the tournament.

Photo: Record.pt

The Italians redeemed themselves somewhat in 1951 as the Gre-No-Li (AC Milan’s all-Swedish front three made up of Johan Gunnar Gren, Gunnar Nordahl and Nils Lielholm) fired Milan to a 5-0 victory over Lille in the final at San Siro.

Lille were stand-ins for French champions Nice who instead chose to go to the newly established Rio Cup in Brazil, an invitational, intercontinental tournament looking to usurp the likes of the Copa Latina. The Copa Latina semi-final between Lille and Sporting was as convincing an argument as any to keep eyes wandering to Brazil, however. After a 1-1 draw, the two teams played out a 6-4 in the replay.

The tournament was given a reputation boost in 1952 when Barcelona were victorious in Paris. The Catalans, led by the generational Laszlo Kubala and managed by his father-in-law Ferdinand Daučík, became known as “Barça of the Five Cups” in Spain as they enjoyed a clean sweep of La Liga, Spanish Cup, Copa Eva Duarte, Copa Martini Rossi and Copa Latina.

The 1951-52 season is – in the eyes of Barca fans – more impressive than anything Real Madrid managed in the same era, even their five consecutive European Cups. Their victory sparked wild celebrations from the many Catalans in Paris who had been exiled by the Franco regime.

That was the end of the first four-year cycle. Barca’s two wins mean the Spanish federation received the gold cup. France came second in the four-year table courtesy of their three runners-up finishes, but as the only federation not to win a Copa Latina, their press was not happy.

“Reims [French representatives] Top in French, Bottom in Latin,” one headline read. That the final took place a week after France’s national team lost to Spain did not help.

Format changes – such as turning the Copa Latina into an international competition – were pondered between the two cycles, but discussion never bore fruit. The 1952 tournament had been the only financially productive event and with competition from tournaments like the Copa Rio and the newly revived Mitropa Cup hotting up, change was needed.

The French were thankful for the organisers’ inaction, however. They won their first trophy in 1953 as Stade de Reims beat AC Milan 3-0 in the final in Lisbon, the imponderable Raymond Kopa scoring twice.

Photo: Sports.fr

With the World Cup in Switzerland taking place in 1954, the Copa Latina had learned its lesson. No tournament took place that year. When it returned in 1955, the footballing landscape looked very different.

UEFA was founded in June 1954 and – in direct response to Wolves’ 3-2 victory over Budapest Honved which led to manager Stan Cullis labeling his side “Champions of the World” – the European Cup was born. It was a death knell for the Copa Latina.

Real Madrid won the last edition of the competition to take place before the creation of the European Cup. The tailspin of the tournament’s once-distinguished reputation was illustrated when Milan hosted the 1956 event and chose to host the tournament, not at the San Siro, but the crumbling Arena Civica, a small multi-purpose stadium which was already over one hundred years old. “Has Milan killed off the Latin Cup?” asked France Football.

The final tournament was held in Madrid and was actually one of the more successful iterations. Madrid won on home soil, there were excellent attendances, and Spain once again came out on top at the end of the four-year cycle. But the organisers knew its days were numbered.

Photo: Diario AS

That was that. Real Madrid’s dominance in the early stages of the European Cup captured the imagination of a continent. Once that happened, this four-team tournament didn’t stand a chance.

There were plenty of problems with the Copa Latina. Miroir Sprint said: “the real winner of the Latina Cup was fatigue.” Before cryotherapy chambers, before strict diets, before even warm-downs, the fact that the Copa Latina was held at the end of a gruelling domestic season did not help matters. Players were tired, and the heat on the Iberian Peninsula or in Italy in the summer was not conducive to the kind of football which these events needed to present if they were to be successful.

But it wasn’t a failed experiment. It was a false dawn for a true continental competition, but it brought the cosmic football of great Barcelona and Real Madrid teams to worldwide attention. And in bringing together the four nations, bonds were formed.

In Origins and Birth of the Europe of Football, Paul Dietschy’s remarks on the Mitropa Cup are too applicable to the Copa Latina: “nationalism and national stereotypes aroused by heroic sporting sagas further enhanced the attractiveness of matches while paradoxically setting up annual encounters that allowed a better understanding of each other and, for the duration of a match or a tournament, the establishment of a footballing community.”

We are always borrowing from the past. In paving the way for the European Cup, the Copa Latina lit the fire that we still warm ourselves by to this day.

By: Adam Williams

Featured Image: @GabFoligno