Tactical Analysis: Inverted Fullbacks

There was once a time, when fullbacks were considered the worst player on the team, with a limited influence on the game from an attacking viewpoint, whilst having one main job – stop the opposition wide midfielder. Jamie Carragher once famously quoted that fullbacks were either failed wingers or failed centre-backs. However, Over the past couple of decades, the role of the fullback has become paramount to a team’s success. And in some instances, the fullbacks have become one of the most important positions on the pitch.

Arguably, the shifting point for the importance of fullbacks came during the 2002 World Cup, with Brazil’s marauding fullbacks Roberto Carlos and Cafu on show to shift the stereotypes of fullbacks at the time. Since then, we have seen the fullbacks being used in a number of different ways from attacking outlets to provide penetration in wide areas and hit the byline, such as Dani Alves under Pep Guardiola at Barcelona, to a newer role of an ‘inverted fullback’ a modern take on the role that is popping up across the world. This analysis takes a look at the ‘Inverted Fullback’ from a technical and tactical viewpoint, using examples from different managers and teams that have utilised the role.

In Possession

Before the shifting of attitudes to the importance of fullbacks, the position was primarily used as a defensive one, contributing less to building the attack as opposed to other formations. Particularly in England during the late 90s and early 2000s, where a lot of teams would operate in a 4-4-2, fullbacks, whenever they got the ball were tasked with a simple pass laterally to the central defenders, a vertical pass to the wide-midfielder operating in just advanced of them, or a hopeful punt into the channel.

However, fullbacks now have a lot more responsibility to be involved in building the attacks from deep, this is especially apparent when it comes to inverted fullbacks.

Build-up

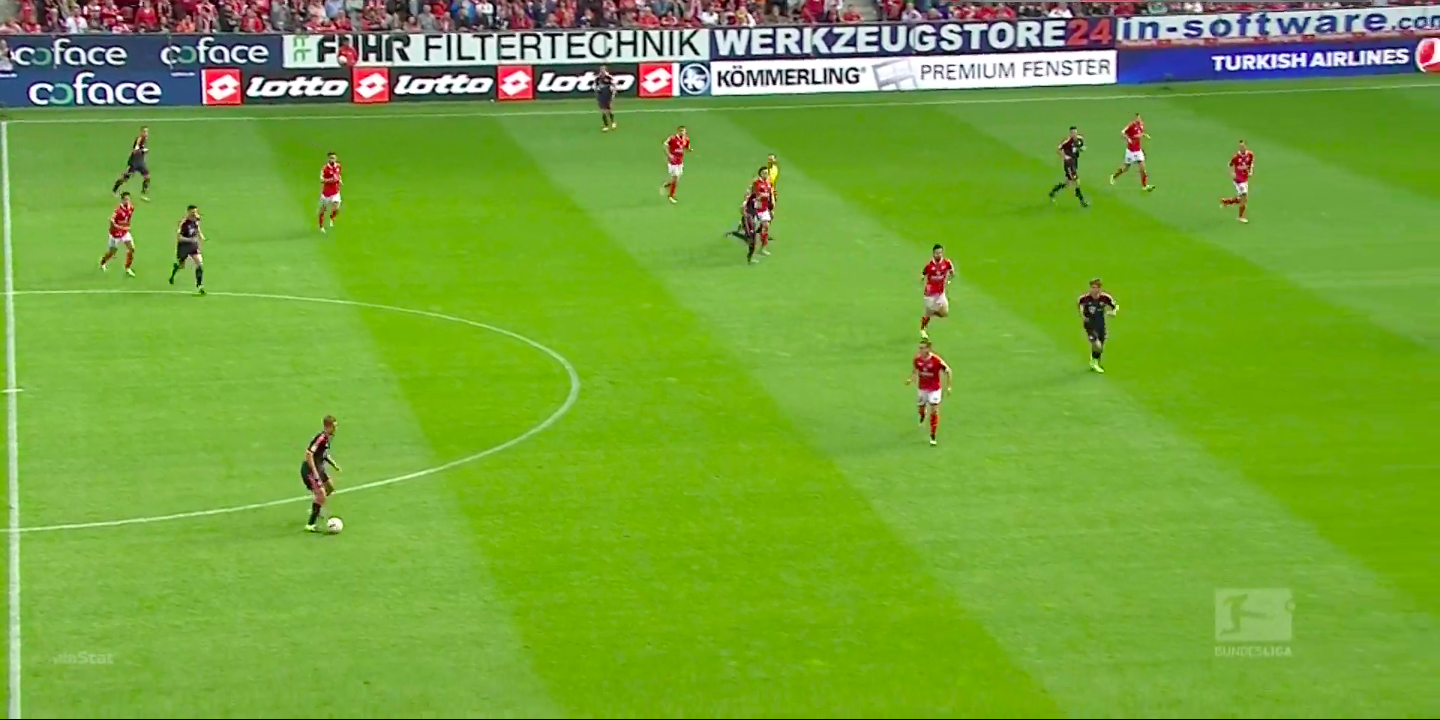

As previously mentioned, fullbacks have a more active role in the build-up of attacks, especially when playing in teams that like to play short from the back and play through the thirds. An excellent example of how inverted fullbacks are of importance to building the attack, and arguably the most notable inverted fullbacks, Phillip Lahm and David Alaba whilst playing for Bayern Munich under Pep Guardiola.

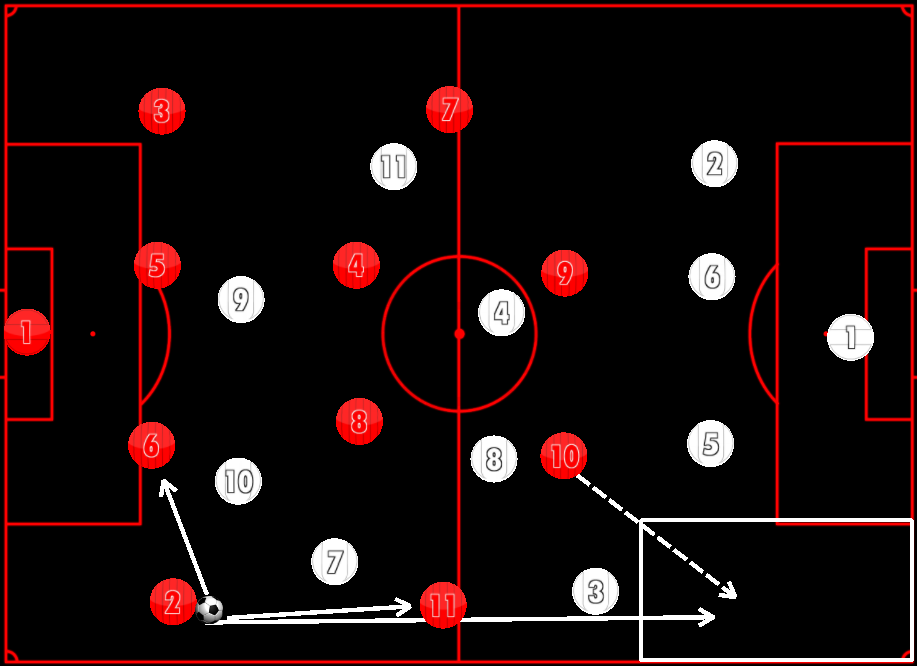

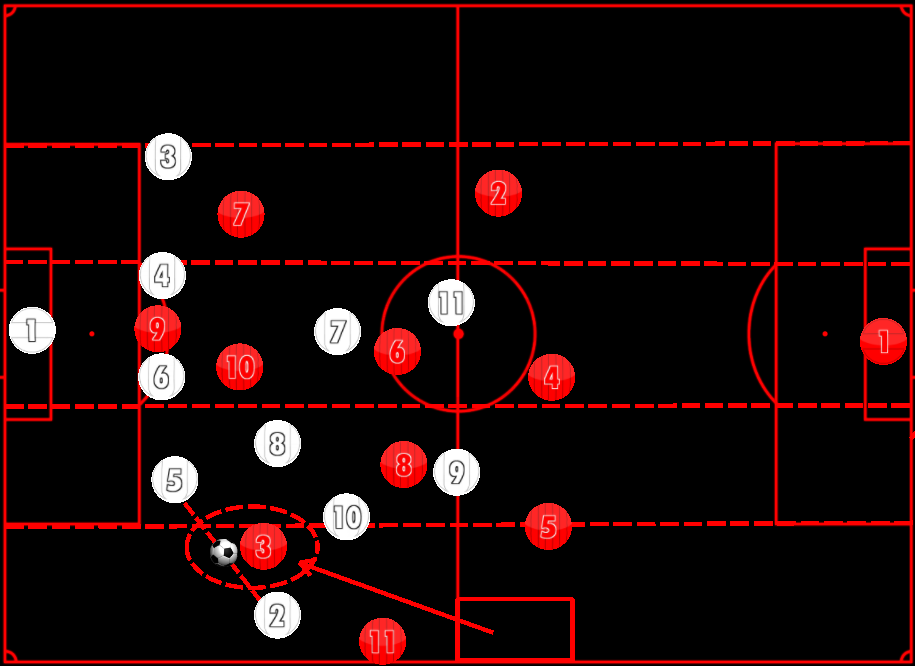

With the fullbacks inverting more centrally, the formation, when typically playing a 4-3-3, shifts to more of a 2-3-2-3 as shown below. This switch creates a three-man pivot when building the attack. The three-man pivot offers more passing options when playing out from the back, through the thirds, and is most effective when playing through the press. As a result of using the inverted fullbacks in this role, it can be a method to outnumber the opposition in midfield 5v3.

When in the build phase, The inverted fullbacks in Guardiola’s system, in particular, Phillip Lahm would shuttle into the half-space to support the build-up. This, in turn, would allow the winger on Lahm’s side to provide the width, with the central midfielders able to advance to find pockets of space.

Also, when in the create phase, Lahm would stay more central and deeper, to find positions to offer a passing option, which enabled Bayern to retain the ball. Lahm’s quality of penetration when in possession meant that these areas he picked up could harm the opposition, either through a diagonal ball to the opposite flank or a punched pass into a more advanced player, breaking the lines.

Attacking Runs

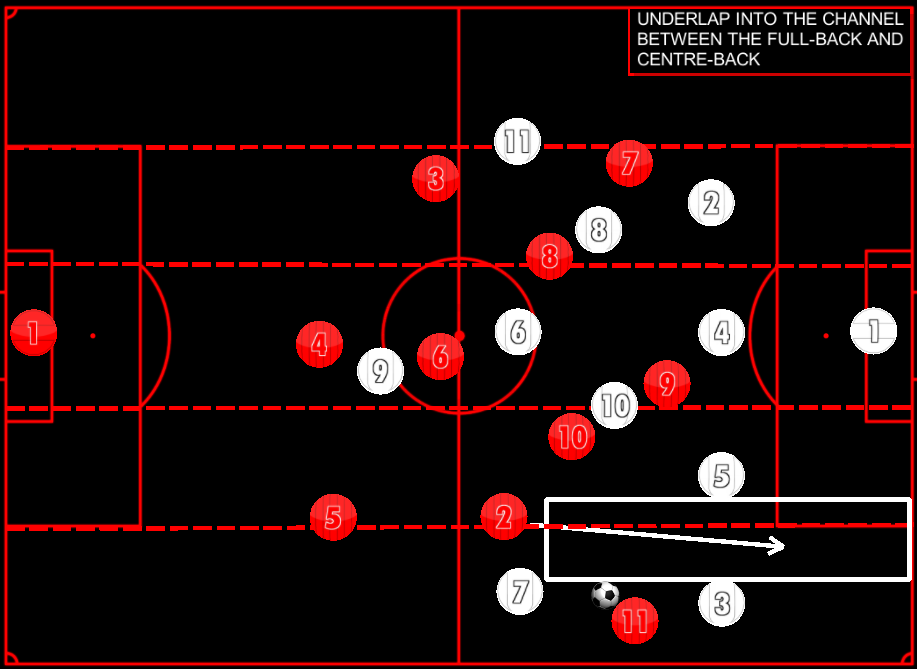

The fullback, even when inverted plays a crucial role in the finishing phase, or the final third. The inverted fullback can still overlap the winger in some instances, however, the majority of the time, the inverted fullback will look to create an underlap in the half-space as opposed to creating an overlap.

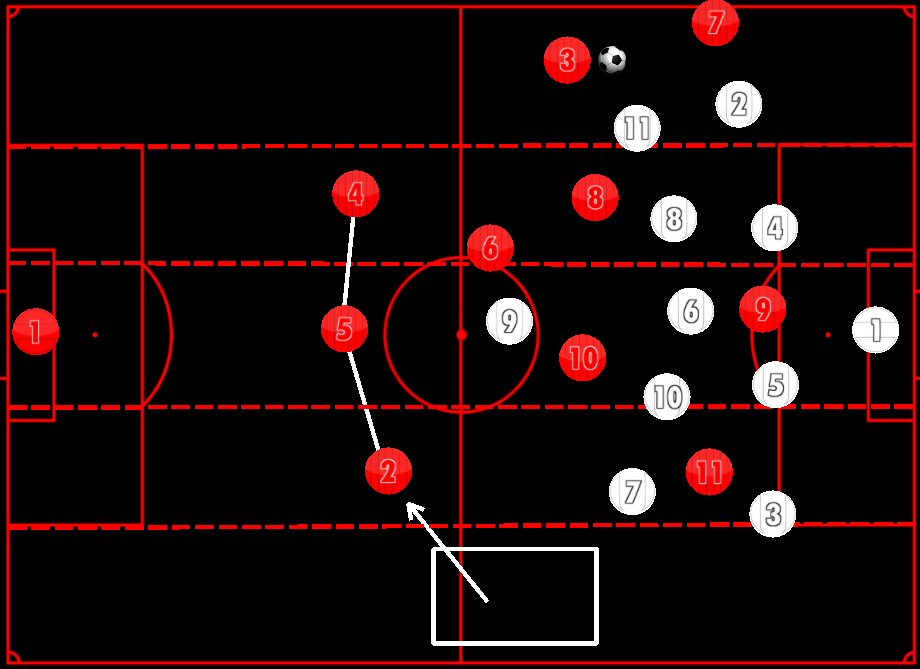

Zinedine Zidane’s Real Madrid has been an advocate of using underlaps as a method of penetration. Marcelo and Ferland Mendy have been the most notable in Real’s side for using underlaps. The already central positioning of the fullbacks in these instances make an underlap a more natural run, instead of an overlap, especially given how wide the winger is.

With the winger being so wide, it looks to draw the opposition fullback out of position, which aims to create a channel in-between the fullback and centre-back that can be exploited via an underlapping run. As a result, a cut-back to the penalty spot can be made from the byline for onrushing players, making it very difficult to defend.

Luke Shaw, of Manchester United has also been excellent at making underlapping runs this season, which has coincided with an upturn in form since making the left-back spot his own, back from new signing Alex Telles.

The position Shaw operates in now is in the area where he attempts his passes/crosses to try and penetrate. In this instance, against a 5-3-2 formation that Sheffield United operated in, he would look to operate in the spaces between the centre-back and wing-back, below is a clearer demonstration of the positionings Shaw operated in when he came on.

Defensive Solidity in Possession

Whilst not necessarily a role that is construed as making a fullback inverted, it can be appreciated that a narrow, central fullback can create balance and control to a team that is in possession and attacking in the final third of the pitch.

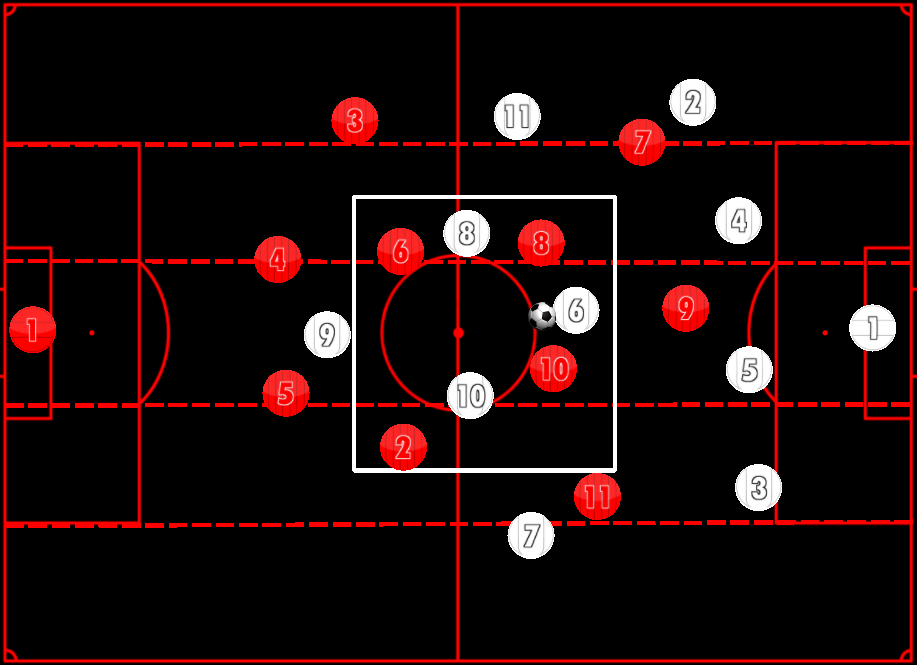

Some teams in recent years, most notably teams that are considered ‘underdogs’ have identified the ‘fullback’ as somewhat of a defensive insurance when attacking. For example, if a team is attacking down one side of the pitch, the fullback on the other side of the pitch will tuck in to create a three-man defence to protect against a potential counter-attack.

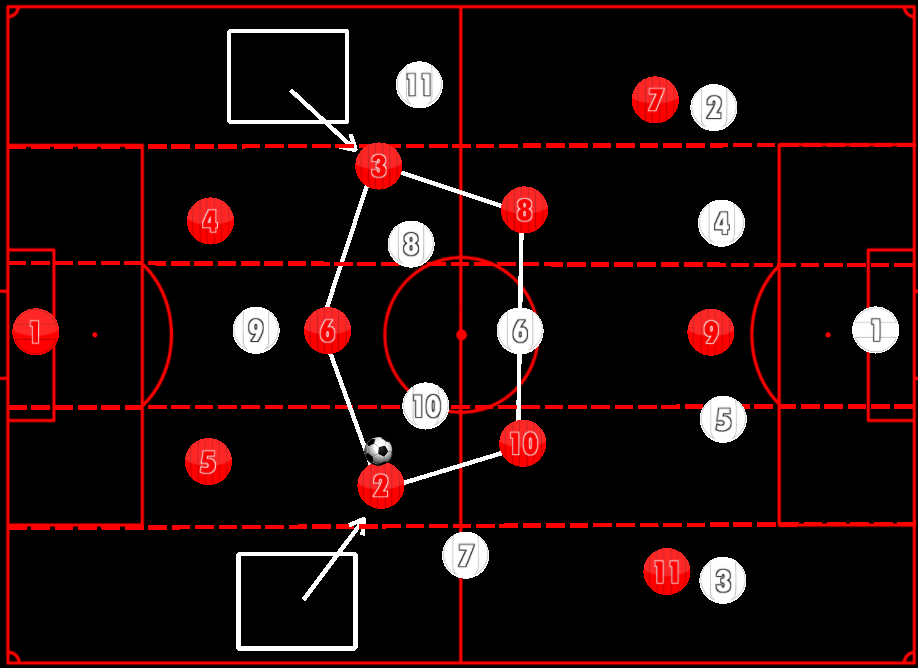

Reacting to the Transition

Naturally, when fullbacks invert into more central areas during the build-up and when in possession, it can create more defensive solidity should the team lose possession and enter a defensive transition. Like the diagram earlier in the piece, inverting the fullbacks creates a midfield overload, not just in possession but also when entering a defensive transition, which makes it easier to initiate a man-oriented press, as there is a numerical superiority, or, at worst deflect the play and deny the space, to be able to allow the team to react and regain their defensive organisation.

Popular Misconceptions

With the rise in popularity and awareness of such a role, there have been some misconceptions about the role and the personnel that fill the position. The main misconception associated with this role is a right-footed player playing a left-back and vice-versa. This misconception is more identifiable in a technical point of view, more so than a tactical one.

A right-footed player at left back (think of Brandon Williams at Manchester United) will look to shift the ball onto their right-foot, as a result, it can seem like they are playing more narrow and inverting. However, this results in the penetration being central through a pass or sometimes a dribble, more so than their positioning being central.

By: Russell Pope

Graphics: Tactical Pad

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / Matthew Peters – Man United / Alexander Hassenstein – Bongarts