Analyzing the Different Variants of Build-up Play

Football is an ever-changing sport. Patterns and styles of play are always morphing, either into completely different forms or upgraded versions of previous systems and approaches. Such changes are necessary not only for the overall development of the game but also for managers and clubs as they continually find ways to stay ahead of their competitors. However, one component of football seems to change at a faster rate than all the others: build-up play.

From direct long balls to intricate passing combinations, ball progression has always been an essential and key component of the game. Everyone — from clubs to supporters — believes in or has a preference for one specific style or pattern, and while everyone has an opinion, one thing remains clear: there is, and there never will be, one set way of playing the beautiful game.

Goal Kick Scenarios

When teams try to progress the ball from back to front, they have two options: either play the goal kick directly into the opposition’s field right from the off or draw the opposition near them and play around or behind the resulting first phase of pressure. Both options, of course, have their advantages and drawbacks.

The Direct Approach

From the early days of the Premier League, and across most other leagues, teams were far more direct in their approach to ball progression. This was especially true in the Premier League. With teams usually lining up in a 4–4–2 formation and two strikers up top, they were confident that this approach was the way to go.

Although this method can appear clumsy at times, there is a method to the madness, and this was particularly evident during the mid-2010s. From well-executed long balls from keepers to huge overloads in specific areas when balls were pumped forward, there were several tweaks and variations that teams used to gain the upper hand when progressing the ball longer.

In this picture, Shay Given of Manchester City has the ball at his feet. Three City players are near him and could all receive a pass. This consequently draws four Manchester United players into City’s half, leaving United with five outfield players further up the pitch and creating spaces that City could exploit with a direct long ball from the Irish keeper. However, this would require a well-executed long ball to make the most of the likely numerical advantage City has upfield.

Seconds later, City plays a perfectly lofted ball to Carlos Tevez’s head, which he knocks down to the onrushing Shaun Wright-Phillips. In the picture, it is clear to see the spaces that City exploited by simply drawing United players into a press and positioning their players — in this case, Tevez — in the perfect position between the defence and the midfield.

From this simple passage of play, City now has three viable options to progress the ball through acres of space, allowing for easier ball progression in the final third of the field. It also buys them time to assess their options, as four United players are still up the field when the ball is played, leaving United’s last line of defence isolated. A simple, direct, yet brilliant way to beat a press and progress the ball from back to front in seconds. With the right goalkeeping profile, this pattern of play can be a great weapon for fast, efficient progression.

Second-phase and third-phase pressure is a tactic many managers use to gain a territorial advantage in the opposition’s half straight from long goal kicks. The idea is to overload one side of the pitch with as many players as possible to create a substantial numerical advantage. Once this advantage is achieved, teams have a higher probability of reaching loose balls or knockdowns quicker than the opposition, allowing them to progress the ball rapidly while also gaining a territorial edge in the final third.

In this picture, following a long kick from Edwin van der Sar, a City and United player contest the ball in the air on one side of the pitch. Although the City player reaches the ball first, United has a higher number of players in the blue region due to the overload created by pushing Rafael, the full-back, and their entire midfield across to that side. As a result of this overload, they are able to regain possession, and Rafael, like his keeper, plays the ball down that same channel again.

Once again, a City player gets his head to the ball first and plays it forward. However, United has continued their press from the second phase of the sequence to the third phase. This has resulted in them having good numbers in a particular pocket of space, ready to intercept any loose ball and progress the play from there.

The ball ends up with Nani, who then lays it off to Wayne Rooney in a good pocket of space high up the pitch. Rooney has time and space to pick his head up and play his next pass — exactly what every manager wants: space and time for players to see and execute the right pass. The move concludes with a shot on target from Ryan Giggs at the edge of the City box.

Although this tactical tweak may not be as fast as direct balls hit from the keeper to outfield players, it is a great way to gain an advantage in the final third by continuously positioning players in areas where they can exploit spaces where the ball is likely to drop.

It provides players the opportunity to get into favourable positions up the field while also increasing their options on the ball. Its speed may not always be the quickest, but like a scrum in rugby, it gradually gains territory up the field until an opening is eventually created.

Long direct balls are an efficient and quick way to turn the opposition over and put them under immediate pressure. While it may not be as aesthetically pleasing as passing out from the back or intricate one-touch play, it can certainly be effective with the right player profiles and talent in the team.

The great thing about this approach is that the profile of the players needed to implement it is not rare at all. Keepers who are comfortable on their feet, intelligent and hungry pressers of the ball, and front men with good hold-up play can all be found with proper scouting and recruitment.

Although it may not always work, it is a potent option for teams that favour fast, quick progression up the field. From long punts up the field to carefully lofted balls to strikers, this approach has evolved over the years and will continue to do so as tactical ideas and methods develop and improve.

Passing From the Back

In the 2009 UEFA Champions League Final, the world was introduced to a new style of progressing the ball up the field. Two centre-backs split wide, with high and wide full-backs and multiple interchanges in the middle and up front. Pep Guardiola masterminded one of the greatest UCL final performances in history, leaving the press wondering exactly what they had witnessed. From the setup to the bravery in passing out from the back, Manchester United just could not find an answer against this intricate style of play.

Building up from the back can be an excellent way to evade pressure and create a large area of space for a team to exploit up front. It involves drawing or enticing the opposition closer to your own goal and playing through them using patterns and positional movements to progress the ball from one end of the pitch to the other. With the right profile of players, it can be very difficult for any team to press effectively against this approach.

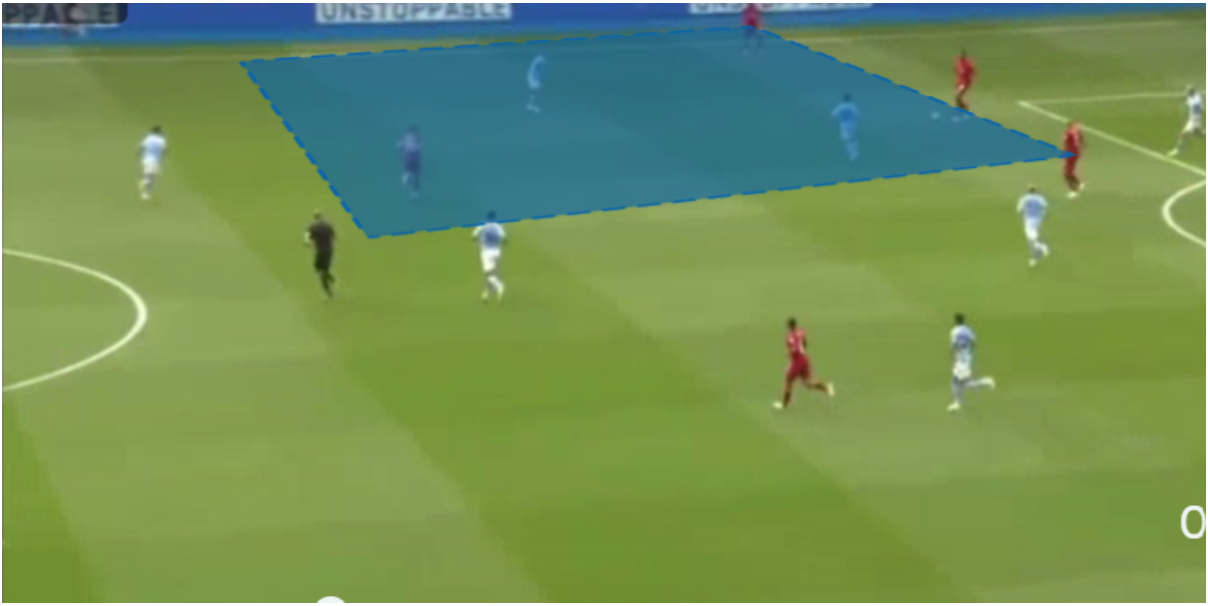

In this picture, Virgil Van Dijk has three options for a pass. He can either play the ball back to Alisson, out wide to Andy Robertson, or pass sideways to Joel Matip. The numerous options available give him more time on the ball because the presser, in this case Erling Haaland, must not only press Van Dijk but also attempt to block any possible passing lanes. This situation provides Van Dijk with more time and space to make the short pass or even go longer, thanks to his exceptional long-passing and diagonal range. He proceeds to pass the ball to Matip.

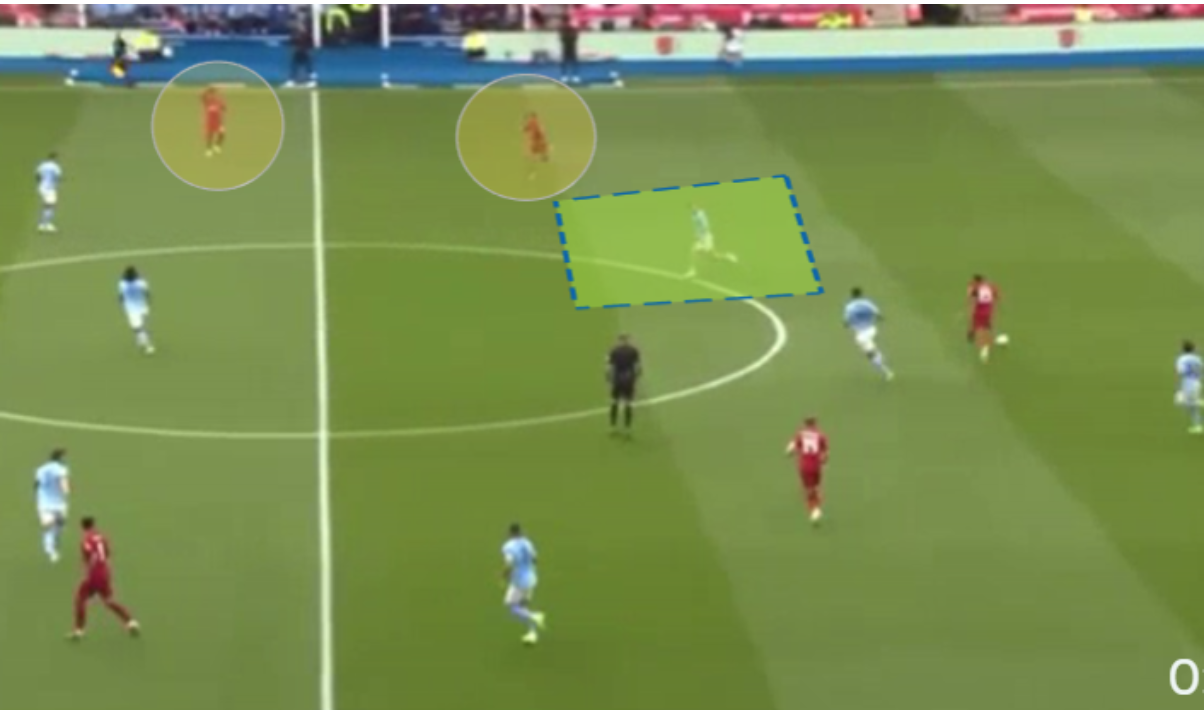

Matip then uses the extra time created by the greater passing options to stride out with the ball. The position of the four Liverpool players in the indicated region of space again creates a conundrum for the two City players in that region. They cannot jump out to press as effectively as they want to because of the position of Jordan Henderson in behind them, thus again creating more time for Matip to assess and deliver his next pass. He decides to pass it out wide to Trent Alexander-Arnold.

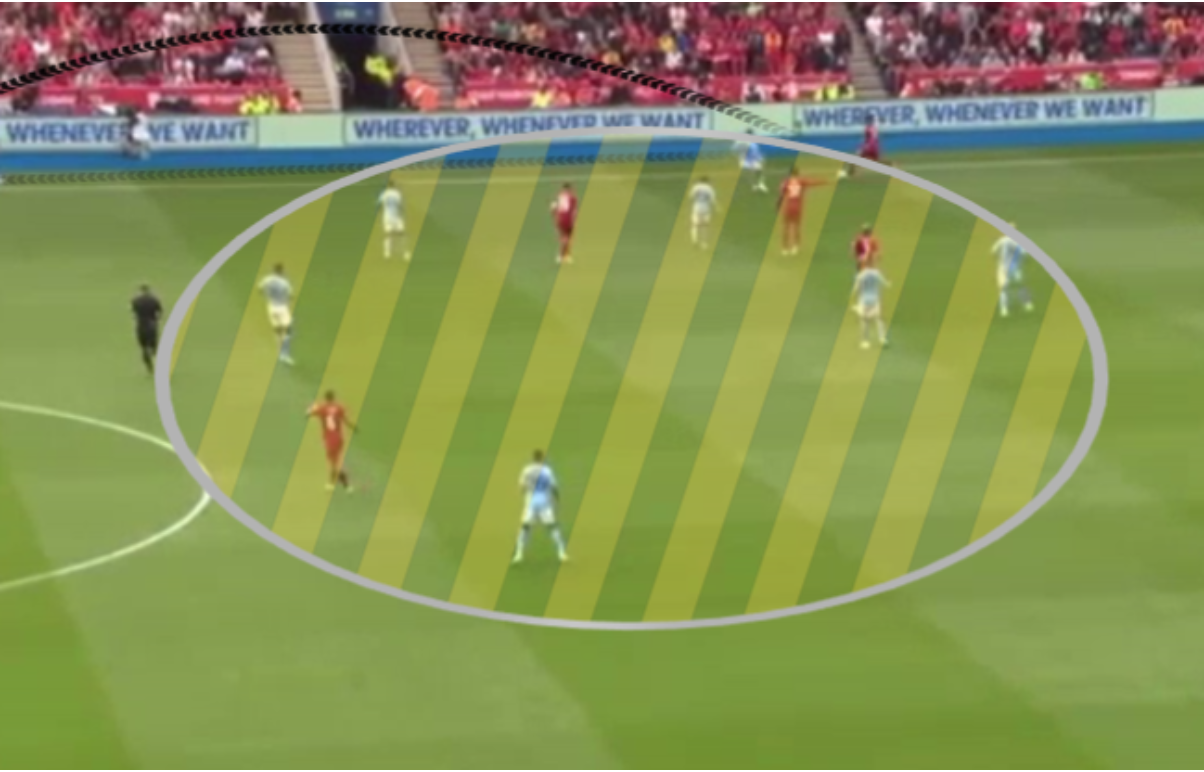

He then uses the extra time created by Jordan Henderson’s presence behind the City midfield to play a long ball forward to that side of the pitch (indicated by the black line), aiming to turn City over. With seven City players compared to five for Liverpool, the Reds have a numerical advantage up the field. They can exploit this advantage to isolate City’s last line of defence.

A City player gets to the ball first, but it then falls to Thiago in space in midfield, who plays a forward pass to Fabinho, also in space. In this picture, it is clear that Liverpool’s front line has managed to isolate themselves one-on-one against City’s last line of defence.

Fabinho also has plenty of time to choose his option with his head up. By drawing the opposition close and positioning players strategically to make the pitch as large as possible, more time can be created for players to pick their heads up and deliver passes forward, as well as isolating defenders with front men positioned higher up the pitch.

In this picture, Van Dijk again has plenty of time to pick his head up and decide which option to pass to. The position of Matip, wide at the edge of the box, provides Van Dijk with this time, as it makes it difficult for the pressing striker, in this case Erling Haaland, to close him down quickly and effectively.

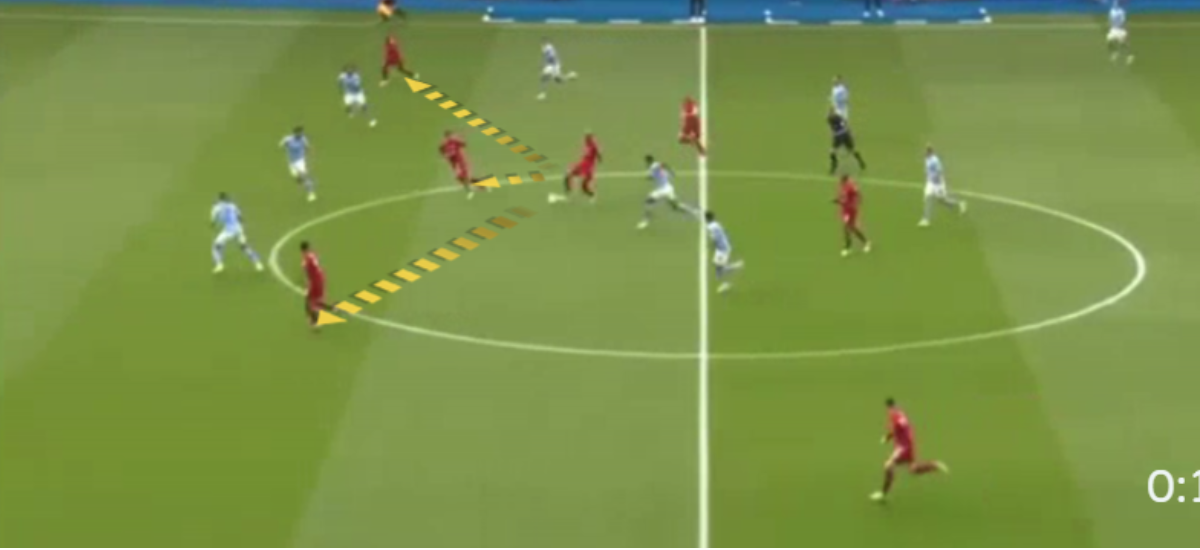

This situation forces Kevin De Bruyne to vacate his midfield position to apply some pressure on the Dutchman, thereby opening up space in the middle of the park. Van Dijk proceeds to pass the ball to Andrew Robertson, who then knocks it down the line to Luis Díaz.

From the picture, we can see that Kyle Walker has tightly followed the Colombian into his own half. However, due to the large space in midfield created by Rodri moving to close down Thiago and De Bruyne moving to close down Van Dijk, Díaz can now progress the ball easily with a single pass into the space vacated by Manchester City’s midfield and occupied by Jordan Henderson.

Díaz decides to pass the ball to Thiago, who quickly returns it to him, giving him the time and space to pick his head up and survey his options, and he then chooses to pass to Salah. It is evident that both Salah and Alexander-Arnold are unmarked on that side of the pitch. This is because Grealish (in the box) has moved from his left-wing spot towards midfield to thicken up the midfield and close the gaps and spaces left by De Bruyne and Rodri.

This movement isolates Salah and Alexander-Arnold against Nathan Aké, providing the Reds with an opportunity to once again isolate the last line of defense. Within seconds, the ball has progressed from Liverpool’s own box to Salah, Liverpool’s most dangerous player who now has time and space available to him.

When executed effectively with the right talent profile, this intricate style of play produces more isolations and overloads across the pitch due to the knock-on effect created once the first phase of pressure is bypassed. Teams can be pulled apart by the tendency of players to press and vacate areas on the pitch in order to apply pressure when building out from the back. Once one player makes a mistake and is drawn to press, a knock-on effect is created that opens up and creates spaces all over the pitch, which can be exploited.

Conclusion

There are many approaches and patterns that can be utilised when building play from the back. Over the years, these approaches have been improved, stripped back, and tweaked to enhance how teams progress the ball from back to front. Each approach has its flaws and strengths and can only work with the right personnel and talent profile to execute specific actions at the right times.

Although these patterns or approaches can be termed strategies, they are merely structures that teams use to solve particular problems at specific moments in the match, as different questions will be asked as the contest progresses. The best teams, like Liverpool and Manchester City, understand this and adapt or use the style that suits the situation best, working within that framework or structure.

Coupled with the creativity that comes when teams are allowed to problem-solve on the pitch within this structure, teams can achieve great success when they are fluid and adaptable to whatever challenges arise. The best teams don’t rely on just one go-to approach; they have several and can employ them at any time.

By: Mark Bruce / @MarkV_Bruce8

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / Getty Images