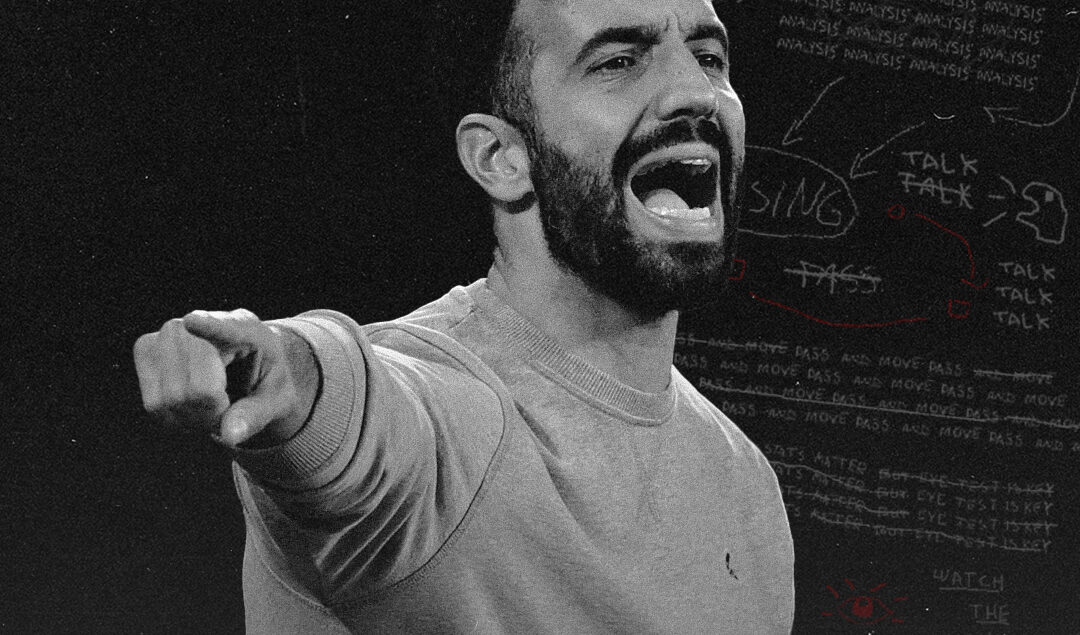

Analyzing Rúben Amorim’s Start to Life at Manchester United

Manchester United’s first month under Rúben Amorim has been an eventful one. The team won a very emotional derby game and secured a place in the top-8 of the Europa League, but were frustratingly eliminated by Tottenham in the EFL Cup and had a disastrous match in terms of defence on corners against Arsenal.

Regardless of the outcome, Amorim emphasises the importance of the level of play during his press conferences, as well as the players’ acceptance of his ideas and principles. This text is a snapshot of Amorim’s first impressions of his start at United: what of his ideas is already working, and what needs a long refinement.

Build-up

Since the arrival of the new coach, United will now launch attacks very patiently. The central defenders hold on to the ball and do not hurry with progressive passes if their partners are not in the right positions – wingbacks on the touchline, the CMs and two interiors above them in the form of a trapezoid in the centre of the pitch. Bruno Fernandes is the conductor of Amorim’s ideas on the pitch: very often the captain gestures to his partners to calm down and not to hurry.

The team is still in the early stages of its development, so possession was sterile in some matches, especially in games against low blocks. Players rolled the ball around in a U-shaped trajectory, rarely escalated play with passes between the lines, and there was no space to pass behind the back due to the opponents’ deep defence. United have twice gone over 70 percent possession this season, both times under Amorim.

In addition to the global principles – maximum width from the wingbacks, trapezoid in the centre of the pitch – the Portuguese coach has already implemented some specific combinations in build-up phase, that he used at Sporting, such as the movement of the centre-back from the back three. Against actively pressing opponents, in possession and goal kicks, Matthijs de Ligt rises and takes up a position on the same level as the central midfielder. At the same time, the outside centre-backs spread out wider, approximately to the side of the penalty area.

Five players in deep positions lure the opposing players into pressing. The strategy is certainly risky, but the team has the tools to get past the aggressive pressure.

André Onana remains a very quality goalkeeper in terms of passing, capable of breaking up the opponent’s press with any pass – a diagonal to the flank, a vertical behind the back, a pass between the lines. Despite a series of mistakes in mid-December, there is no need to worry about Onana’s form and mental state. Last season he already proved that he is capable of deflecting criticism in the media and concentrating on the game.

In addition to shifting the CCB into the midfield, United regularly utilise another movement pattern based on the use of inverted wingbacks. If the team is locked on the flank, the outside centre-back will pass to the wing and the wingback will make a one-touch pass behind the back to the forward or inside. An alternative scenario for passing on the wing is to pull as many opposing players into the area as possible and break up the pressure by switching to the opposite flank.

Amorim also has ideas for specific opponents. Against Nottingham Forest’s deep, tight defence, with minimal space between the lines, De Ligt would go with the ball almost to the centre of the pitch and stand with it for 5-10 seconds, waiting for pressure from Chris Wood.

If the New Zealander didn’t press, De Ligt would give a pass back to Lisandro Martínez or Leny Yoro, which was the trigger for the opposing wingers to start pressing. As soon as they advanced on the outside centre-back with the ball, several United players would make an opening deep in the centre of the pitch, including Rasmus Højlund. This kind of movement wreaked havoc on Forest’s defence, central defenders were not always able to keep up with United’s attacking trio, which led to a goal in the 17th minute.

Positional attack

It’s impossible to set up a positional attack in a month, so Amorim still has a lot of work to do in this aspect, but the first traces of his system are already visible. The first thing I would point out is the coordination within the flank triangles when passing behind the back.

Before making a back pass, the team is arranged in a 3-2-5 formation. If the players are in the right positions and the outside centre-back receives the ball without pressure, the nearside inside bounces under a short pass and lures the opposing defender out of the area.

A partner – either wingback or Højlund – is sure to run into the vacated space. The Dane made vertical accelerations through the half wing in the style of Viktor Gyökeres back in Atalanta, so Højlund feels the moment for acceleration well and rarely gets caught offside. In some cases, the players switch roles and the inside accelerates behind the back, but even more rarely the CM makes a run from deep.

Such combinations are more likely to take place on the left flank for two reasons. Firstly, Martínez’s passes and vision of the pitch is better than any of United’s centre-backs, even despite Noussair Mazraoui’s progress. Secondly, it’s more comfortable for Højlund to make bursts through the left flank. On the right, he spends extra moments receiving the ball with the weak foot and slows down the attack.

In recent games United have started to utilise another tool built on vertical passes, the most telling example being Amad Diallo’s winning goal in the derby. As soon as Martínez received the ball without pressure, Diallo started a diagonal acceleration behind the back. It is very difficult for defensive players to control such spurts.

Following the opposition would open up the option of switching to the far flank. United used this in the cup game against Tottenham – Bruno Fernandes dribbled Pedro Porro into the middle, clearing space for Diogo Dalot. It’s also dangerous to pass the opponent to the centre-back at the moment of the pass, as you risk choosing the wrong timing and leaving the runner unmarked. City don’t practice the offside trap option, but even with it, diagonal sprints pose a greater threat to the defence than vertical ones.

Matheus Nunes played on the left side of the defence for the first time in his life and it’s hard to criticise him, but in the episode with the second goal he made the worst decision possible – he didn’t make up his mind. First, he ran after Diallo, but immediately missed him and dropped the line by a few metres, then he stood up relying on Joško Gvardiol, who was no longer able to keep up with the Ivorian.

Because of the tight calendar, Amorim rotates the squad a lot. Højlund is replaced by Joshua Zirkzee, who gives the Portuguese coach the opposite option in the centre of attack. Instead of running in behind the back, the former Bologna player bounces deeper, for example, to offer and address between the lines for outside centre-backs.

Zirkzee feels comfortable in tight spaces and is rather technically gifted for his size – he works quickly with the ball, plays short one-touch passes with his partners, and uses backheels. Added to his technique is his good vision of the pitch: when receiving the ball with his back to the goal, Zirkzee not only plays back, he can turn the game with a switch or find a partner with a through ball.

It’s no coincidence that Amorim has used Zirkzee on several occasions as an inside. But sometimes the Dutchman is let down by his decision-making – he either puts too much faith in his dribbling, or he delays the pass and loses the ball.

If a team is attacking wide on the flank, filling the penalty area is very important for Amorim. At Sporting, along with Gyökeres, there were always 2 extra players running in there – a wingback and one of the centre midfielders. Dalot and Amad Diallo have learnt this principle well from the new coach and regularly go to the far post when there is an attack on the opposite flank. The central midfielders are still not so good at reading the moment to run into the box, but Kobbie Mainoo and Fernandes have already struck a few shots after such passes.

In addition to crosses, United often create 1v1 isolations for Diallo in flank attacks. The tenacious Ivorian is in great form, with the ball in his feet he always aims to beat the opposition with a cut into the middle for a shot or a key pass.

At the same time, he cannot be called limited, Diallo could dribble both inside and outside the pitch. Amad starts very sharply from the spot, small steps quickly gaining speed, keeps the ball close to his foot, and shakes opponents with false pauses and body feints.

Rotations – players, roles, positions

Players are not only rotated amongst themselves, Amorim often changes the positions of specific players from match to match, in particular, Fernandes. Bruno has spent most of his playing time under the new head coach in the attacking three, but in a few games, he has been paired with a more defensive midfielder in the centre of the pitch.

When the Portuguese plays as an inside, he looks for space between the lines, yanking the opposing defence with runs in-behind and occasionally bouncing deep. Amorim moves Fernandes to the centre of the pitch in two diametric cases – against top clubs and against weak teams playing in a low block.

The idea of dropping the Portuguese deep against top clubs makes sense in two scenarios. Against highly pressing teams, Fernandes will be a useful option to pass through the opponent’s pressure. He constantly offers himself for the pass, gives his partners the best options to move forward, doesn’t lose concentration, which is typical of young Mainoo, and doesn’t slump physically like Christian Eriksen.

The second scenario was playing against teams with a lot of possession. In the matches against Arsenal and Manchester City, Amorim concentrated more on destroying the opponent’s ideas, so he released the efficient Mason Mount in the attacking trio. That said, Amorim still has an intention to fight back, it was important for him to keep Fernandes on the pitch.

Bruno constantly scans the space around him, so in transitional episodes, important against such opponents, he only needs a second to assess the situation and make a decision. Adjustments to the game plan had to be made after Mount’s injury, but the opening segment of the game against City was reminiscent of the game against Arsenal.

Several of Amorim’s ideas, tied into the rotations that worked well at Sporting, have yet to be fine-tuned. Firstly, the movement within the trapezoid in the centre of the pitch – so far, United’s players are simply getting into the right positions, but they lack a coherent, practiced, intuitive, collaborative movement. The ball travels slowly, the team’s control often becomes sterile.

Secondly, insider rotations have room for improvement. At Sporting, the left insider often swapped positions with Gyökeres as the attack progressed, and on the opposite flank, Francisco Trincão could sometimes go wide.

In such situations, the right wingback took up a place in the half-space. The seeds of such movement were seen from Marcus Rashford and Tyrell Malacia in the game against Viktoria Plzeň, but so far these patterns are only in the early stages of development.

Positional defence and high pressing

With the arrival of Amorim, United have changed to a zone defence. There are still some elements of personal guarding in the team’s play, such as the outside centre-backs moving after their opponents into high areas, but now every move out of the line serves as a signal for the defensive players to narrow the space behind their partner.

When passing to the flank, United are quick to reorganise and squeeze space. A group of five players – a wingback, an outside centre-back, two CMs and an inside-forward, who actively presses the player with the ball, tight up on the ball carrier. The far inside controls the switch, the striker controls the back pass, but sometimes Højlund doesn’t go deep to be in a better position in case of a counterattack.

When the opponent attacks down the flank, the centre-backs in the penalty area are half-turned to the ball. It is important for them to control not only the players in the penalty area, but also the height of the defensive line – when opponents pass back, they must take 1-2 steps forward in a coordinated manner. A similar mechanism works when passing behind the back, De Ligt commands the line, regularly prompting his partners with gestures.

Against crosses, the players in the penalty area are switching to a man-marking. For example, in the derby with City, Martínez played very tightly around Erling Haaland, and in the match against Nottingham Forest, Yoro and Wood regularly met in the penalty area.

The young Frenchman lost several key 1v1 battles, particularly in the third goal episode. Wood either nudged his opponent slightly or dived sharply behind Yoro’s back as the serve went on. The United defender had no time to coordinate and missed his opponent.

Under Amorim, Sporting defended in a 5-2-3 formation in the mid-block. In the match against Arsenal, the team played in a similar fashion, defending at a level just above the centre line, sometimes moving up to David Raya’s penalty area.

The centre was tightly covered by the top five players – the attacking trio turned on the pressure after lateral passes between CBs, the central midfielders finishing off their opponents from the back. If United do roll back into their own half, the formation is rearranged to the classic 5-4-1, less often to 4-4-2.

The wingback and an inside midfielder on the opposite flank become the wingers, with a second inside midfielder moving into the forward line. Similar rearrangements were seen in the games against Ipswich and Everton.

Against City, Amorim had an atypical game plan. In a midfield defence, Diallo regularly moved behind Gvardiol into the centre of the pitch, leaving his flank empty. Matheus Nunes took advantage of the free space and carried the ball into the other side’s half on several occasions.

The pressing under Amorim has become a little more aggressive and the team has started to tackle more often in the other half, but the Portuguese coach is definitely not a high-pressure dogmatist. In the context of pressing, the preparation of the coaching staff for the game against Tottenham stands out.

Due to numerous injuries, Ange Postecoglou was forced to release Radu Drăgușin in the centre of defence, who is mediocre at advancing the ball. United adapted to this weakness – when passing to the Romanian, Højlund started pressure and blocked the back line of the pass, while his partners sorted out the closest recipients. Drăgușin was forced to look for difficult progressive options and gave away possession several times.

Transitional episodes

Transition episodes are very important for Amorim. The players need time to assimilate the principles of the new head coach, but even at the stretch of a month, progress can be seen in defensive transitions. In the game against Ipswich, the team regularly collapsed after losses, with players reacting erratically to inaccurate passes.

Ipswich took advantage of this and created several chances in such episodes, accentuated through Jonny Evans’ area – the experienced defender was forced to regularly play 1v1 in space against the fluid Omari Hutchinson and expectedly lost a few episodes.

One push for progress in defensive transitions was the integration of Manuel Ugarte into the line-up. The Uruguayan has played 85 games for Sporting under Amorim and already knows what the coach wants when the team loses the ball, so he rarely makes wrong decisions in such episodes. Ugarte is very good without the ball, not only technically but also mentally.

The Uruguayan switches quickly and is tenacious and aggressive when attempting to tackle. The downside of Ugarte is his ball-playing, he doesn’t always find the option to advance after a successful tackle, slowing down the attack with passes back or shutting it with inaccurate attempts to progress the ball.

In addition to Ugarte, it is the competent positioning of the centre-backs that allows them to stifle counter-attacks at the initial stage – against opponents playing in a low block, the entire back three regularly move up into the other side’s third. When United lose possession, they are very compact, with players able to tackle immediately, quickly regain possession, and continue to shut down their opponents in the box.

In offensive transitions in Amorim’s first few matches, Alejandro Garnacho has been United’s key player. The Argentine, who is in poor form, got a lot of opportunities in fast breaks, but made terrible decisions in the final stages and failed to score. Without Garnacho, the team has become less fixated on one player: United uses vertical passes to Højlund, through balls to insides, and overlaps from wingbacks.

Conclusion

Ruben Amorim has certainly given Manchester United a breath of fresh air. He has turned a difficult calendar with plenty of midweek matches into an advantage, making the players feel important through constant rotation. The team has started to look much more cohesive on the pitch, but Amorim still has a lot of work to do, as he regularly states in press conferences. In particular, the Portuguese coach has to solve the problem with corners, which we will talk about in the next article.

By: @normalnik131

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / Justin Setterfield / Getty Images