“A Cesspit of Lies, Treachery and Whispers”: How Real Madrid’s Dressing Room Transitioned from Ferrari Boys to Galácticos

If it isn’t raw feeling, football fans don’t want to know. Corporatism, footballers who don’t like football outside of their professional lives, empty stadiums, players not celebrating goals – all are treated with undiluted contempt by a hopelessly romantic footballing public.

But the game can be a dispassionate pursuit. Though their supporters might expect them to treat it as a spiritual calling, for many of those out on the grass, it’s a job and nothing more. And – as I’m sure many of you can attest – you don’t always get on with your workmates.

Mind you – while your office might have witnessed its fair share of squabbles, it has almost certainly never been described as a “cesspit of lies, treachery and whispers.” That was a 22-year-old Raúl’s withering assessment of the Real Madrid dressing room in 1999.

Twelve months earlier, the walls of that same dressing room were dripping with champagne after victory in the Champions League Final, in which Los Blancos triumphed over Juventus in Amsterdam. A year after the young Raúl’s damning indictment, they won it all over again, this time against Valencia. Now, two European titles in three years would hardly seem to fit the theory that social disharmony within a squad leads to poor results on the pitch.

Raúl made his comment to the press after Steve McManaman signed for Real Madrid in July 1999 – “if McManaman thinks he is coming to one of the world’s top clubs, then he has made a big mistake,” he said. As welcomes go, it wasn’t the warmest – even for a club with a famously frosty culture.

Along with his Liverpool teammates Jamie Redknapp, Robbie Fowler, James McAteer and David James, McManaman played a starring role in the clique that would become known to the English tabloid press as the “Spice Boys.”

Liverpool were an exciting but underachieving side in the mid-90s, and it’s therefore up for debate whether the white-suited merrymakers were a pernicious influence in terms of results. But while their legacy on the pitch is perhaps not what it could have been, they were at least good mates off of it. The same could not be said for McManaman’s new colleagues in Madrid.

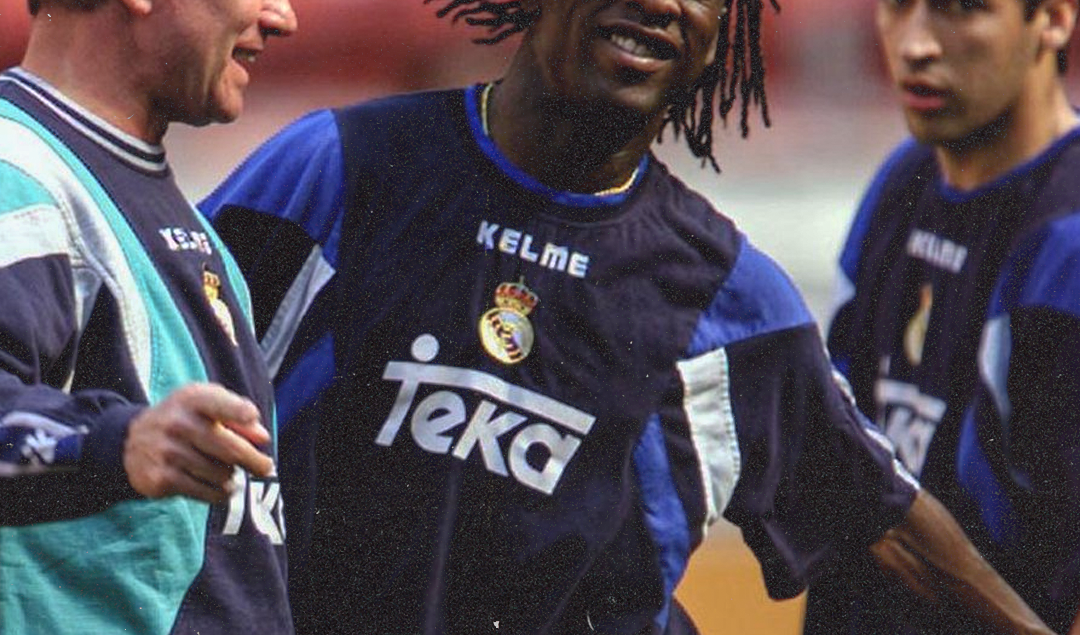

Photo: Mirrorpix

On the day of the Englishman’s unveiling, Fernando Hierro and Clarence Seedorf were involved in what journalistic cliché insists we characterise as a “training ground bust-up.” The scrap – reported in atomic detail by the Spanish press – was highly emblematic of the divisions within the squad.

Hierro formed the upstanding contingent along with Fernando Redondo, Manolo Sanchís and their fiercely loyal understudy, Raúl. Seedorf, on the other hand – along with Christian Panucci, Davor Šuker, Christian Karembeu and Predrag Mijatović – was the nucleus of the “Ferrari Boys,” the faction within Los Blancos’ squad that, while undeniably brilliant, was the subject of intense media scrutiny for their unrestrained off-pitch behaviour.

“They weren’t very pleasant,” said ex manager John Toshack to Diario AS. “They had just won the Champions League against Juventus and they thought they were the bee’s knees.”

Upon being appointed Real Madrid manager for the second time in 1999, Toshack perhaps underestimated the egos in the dressing room and the cultural shift towards player power that had taken place in the 10 years between his two stints in the Spanish capital.

“Having been here before and having been successful, that gives me an advantage over these players – the Seedorfs, the Raúls, the Mijatovićs, the Šukers, the Hierros, whoever they are,” Toshack said. They know someone’s come back, who was here 10 years ago when they were just 10 or 15 years of age. That does command a certain amount of respect.”

The language that the Welshman used – “that gives me an advantage over these players” – hardly paints a picture of the manager and the squad being two horses in a harness pulling in the same direction. Instead, it seemed that any success Real Madrid would enjoy in this period would come in spite of the atmosphere off the pitch, not because of it.

Obvious parallels can be drawn with the Madrid side of the 2010s who – no matter how prolific – always seemed to be flirting with disaster. The club often seems stuck on a rolling boil, searingly brilliant but constantly in constant danger of bubbling over.

Unfortunately, it is almost always the managers who pay the price, and Toshack was no different. He was appointed in February 1999 and was gone by November of the same year.

Photo: Jesus Rubio / Diario AS

Nine months might seem like a fleeting spell, but it was longer than the average tenure for a Real Madrid manager in the 90s. Even Jupp Heynckes, the man who brought Real Madrid their first European success in three decades, was dismissed after less than a year in charge after falling foul of then club president Lorenzo Sanz.

Fabio Capello too was the victim of the political setup at the club – he was shown the door even after winning La Liga in his one and only season at the helm. His dismissal was perhaps Sanz’s biggest misstep; Hierro, Sanchis and company thirsted for the Italian’s disciplinary style, whilst the Ferrari Boys revelled in its absence. Club legend José Antonio Camacho barely lasted a month in charge, while the perma-polite Guus Hiddink was never likely to be the bullfighter who could tame the dressing room – he was in the job for just over half a year.

In theory if not in praxis then, Real Madrid before the new millennium was the platonic idea of a dysfunctional club: playing staff divided, political interference from on high, and an enfeebled manager stuck in the middle. Yet still, the trophy-winning machine trundled on as Real Madrid won their second Champions League in three years in 1999-2000, and then La Liga the following season.

The arrival of new manager Vicente del Bosque as well as the election of a new club president, Florentino Pérez, proved to be the catalyst for this sustained success. Together, they began to usher in a new, galactic era.

Photo: Felipe Sevillano / Diario AS

If trophies are the metric by which Real Madrid measure success, then the years between the start of the Ferrari Boys era and the beginning of the Galácticos era were hardly a nadir. They won La Liga twice between 1997 and 2001 at a time when the Spanish top-flight was not the duopoly we see today – Deportivo La Coruña, Atlético Madrid and Valencia won titles around this time while Real Sociedad and Athletic Bilbao all went close. There were also the two Champions League triumphs, of course.

Where there is no doubt that they faltered, however, was in the Copa del Rey. Spain’s top cup competition is not held in particularly high regard in the country, but in 2001-02, Real Madrid were desperate to lift the trophy, given that the final was to be played at the Bernabéu on the day of the club’s 100th anniversary.

The match took place on March 6, around two months earlier than the average Copa del Rey final is usually played. Madrid had lobbied the Spanish Football Federation to move the date of the final to fit with their centenary and asked that no other football matches be played on that day. Apart from being characteristically self-indulgent, the gesture heaped cranium-crushing pressure onto Real Madrid’s players.

By this time, the squad had a fresh coat of paint. Seedorf and Karembeu – the last of the Ferrari Boys – had left at the end of the previous season, and Luís Figo and Zinedine Zidane had become the first Galácticos. The likes of Raúl, Iker Casillas and Guti had bedded themselves in the first team, while new signings Míchel Salgado and Iván Helguera meant that the squad had largely moved away from the party lifestyle while maintaining – and perhaps even enhancing – its glossy opulence.

But Deportivo de La Coruña proved to be the wet blanket to Real Madrid’s fire on 6 March 2002. To the delight of nearly every football fan in Spain, first-half goals from Sergio and Tristán earned them the victory at the Bernabéu. This new, oh-so-mature Galáctico squad had collapsed under the weight of expectation.

Photo: Deportivo de la Coruña

Thanks to the wizardry in Zidane’s left foot, they won the Champions League at Hampden Park at the close of the season, but after finishing behind Deportivo and Valencia in the league, there was a sense that Real Madrid were flattering to deceive.

The club’s response was as predictable as night following day: more money, more star power. Ronaldo arrived in 2002 and David Beckham came the following year. Now the club faced a new problem. No dressing room, no matter how grand, is capable of comfortably housing that many egos. And while there was little animosity within the squad, the overall atmosphere at the club was unhealthy in myriad ways.

President Pérez’s modus operandi was born of relentless lust for the big name and the marketing opportunities that came with it. It brought Robinho and Michael Owen in later years, but little in the way of silverware until some years later.

His strategy was made plainest when Del Bosque – who won the league with Real again in 02-03 – was dismissed. The Spaniard’s easy-breezy managerial style lent itself perfectly to accommodating the big wigs in the dressing room, and after he left, Real Madrid went three seasons without winning a trophy of any kind.

Photo: EFE

In the end, the pre-Galácticos were the more successful of the two incarnations. Even if the dressing room was the cesspit that Raúl described, it saw more glory than its squeaky-clean counterpart.

Football is an enchanting game. We sell ourselves a naïve vision that the best teams are always made up of the best friends when this is manifestly not the case. It’s only natural; if you see beauty on the pitch, the organic response is to think that it’s backed up by beauty and harmony off it. But the transition from Ferrari Boys to Galácticos lays bare the fallacy in this theory.

By: Adam Williams

Featured Image: @GabFoligno