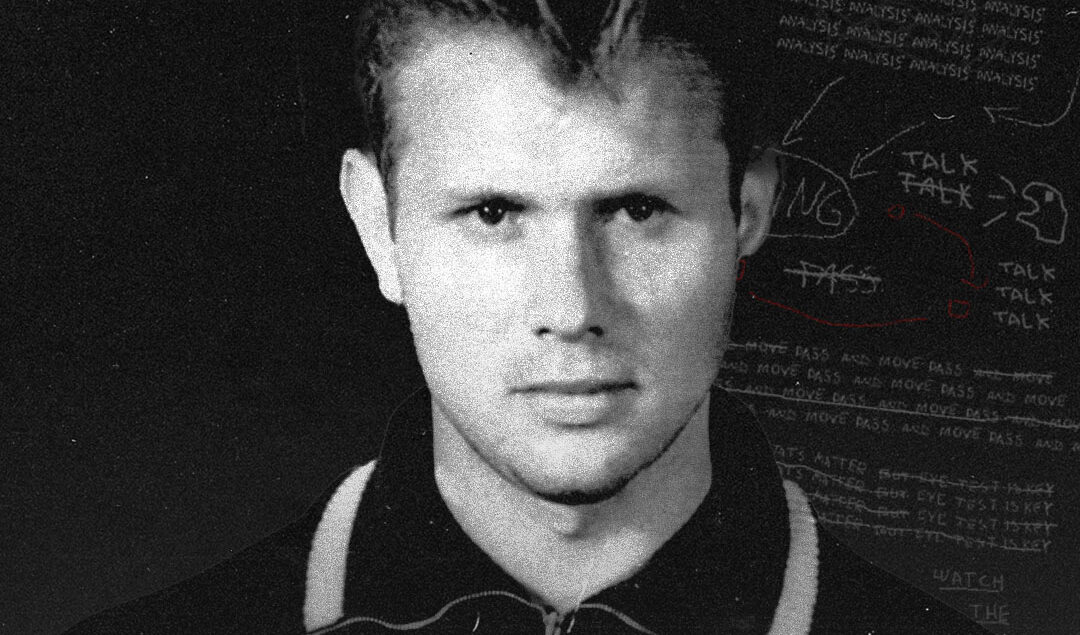

Did the KGB Frame Russia’s Best-ever Footballer?

Any story coming out of the era of Soviet football might seem alien to many audiences and could be filled with tons of “In Soviet Russia” jokes but such levity doesn’t really have the place in a case like this one. Then again, how do you introduce the Soviet league to Western audiences?

Whilst the other Eastern European leagues and countries had players and even managers that went abroad there was nothing as closed off as Soviet football. Established far later than their Western counterparts, it was not until 1936 that the Soviet first division was established at the suggestion of Nikolai Starostin, the founder of Spartak Moscow.

Lacking any remnants of pre-Soviet football, the entire footballing strength of Russia was concentrated in the Moscow teams, CSKA the only team founded before the Soviets took power and the team of the Red Army, Dynamo, the team of the police and KGB and Spartak a trade union team, considered by many to be the team of the people.

Up until the late 1950s, their dominance was near total with one of the three clubs winning every edition of the tournament and often enough occupying every podium position. Back then, there were no other cities that mattered in the Soviet Union and there were no other clubs that mattered apart from the big 3. At least that’s how supporters and officials of the three liked to view the situation.

However, during the 50s, two other teams would start their rise namely Lokomotiv, the team of the Moscow railway and Torpedo, the team of the ZIL automotive plant, which was the manufacturer of the most luxurious automobiles designated for the most equal amongst all the equals. It was at Torpedo that arguably the best Russian player of all time would make his debut at just 16 years of age in 1954.

With Lev Yashin, having made his debut 4 years earlier for Dynamo, Eduard Streltsov started his first season for Torpedo at the opposite end of the pitch and Russia looked to have two of the best players in their position in the world at the same time. Streltsov’s father had fought in the second World War but did not return home despite having survived, choosing instead to settle down in Kiev.

His mother raised him by herself working in a factory, the same factory whose football team gave her son his debut at only 13 years of age. Torpedo later spotted him in a friendly and despite being a Spartak fan, Streltsov signed for them. The term “Starboy” seems to be thrown around football Twitter on a daily basis nowadays but Streltsov really did deserve such a moniker in his first two seasons.

At just 16, he played every game of his team’s side and in his second season he finished as the Soviet top-flight’s top scorer with 15 goals in 22 games. The national team was quick to call him up and he scored a hat trick on his debut against Sweden in a friendly. On his second appearance against India, he scored another hat-trick leading up to his first international tournament at the 1956 Olympics.

Having scored another hat-trick in a preparation game against Australia he netted again to send his side through against Germany in the first game before delivering the performance of his lifetime in the semifinals against Bulgaria. The Soviets went down to 9 men after defender Nikolai Tishchenko and Torpedo forward Valentin Ivanov went off injured, in an era when substitutions weren’t yet a thing, and Bulgaria scored early in the first half of extra time.

Bulgarian Football’s Harrowing Descent into Corruption and Mediocrity

Streltsov then dragged his side by the scruff of its neck to victory scoring the equalizer and setting up the winner. Gavril Kachalin, the national team manager decided that his two forwards had to be teammates at club level and so Streltsov did not play in the final won by the Soviets against Yugoslavia and would not receive a gold medal.

The man who took his place in the Soviet front line, Armenian player Nikita Simonyan, wanted to gift Streltsov his medal after the game but the latter refused stating that he would win a lot of other trophies in his career. If only he knew that his downfall would come less than a year later. 1957 saw Streltsov score the winner against Poland, a goal that meant the Soviet Union would qualify for the 1958 World Cup and helped his club side to second place scoring nearly a goal per game.

Naturally, with such achievements, his superstar attitude and his good looks Streltsov quickly became the heartthrob of the entire Soviet Union. After all sports people or actors were the only public figures young people could idolise, as most girls had no interest in fawning over the politruks or apparatchiks of Moscow.

Streltsov embraced his newfound fame and became somewhat of a party boy, gaining a reputation as a heavy drinker and womanizer. Alongside his Western style haircut, this attitude irked the Communist authorities, as they wanted their superstars to be model Soviet citizens.

Their suspicions that Streltsov was much more than just an 18-year-old enjoying limitless fame were confirmed after a member of his friend group told party officials that he had expressed a feeling of sadness every time he returned to the USSR after a trip abroad.

Those same trips abroad both with the national team and on tour with Torpedo brought him to the attention of clubs in France and Sweden. Possibly knowing that his actions were doing him no favours he continued irking the higher ups, which started using his fame against him. When he was sent off in 1957 in a game against Odessa, Sovetsky Sport, the state sports paper, controlled by the government (like all papers in the USSR) printed an article titled “This is not a hero”.

When he married Alla Demenko in the build-up to a friendly with Romania and during the preparations for the upcoming Soviet season, the state once again took issue with the timing. However, his main enemy in the state apparatus wouldn’t be related to sport or propaganda at all. Yekaterina Furtseva was one of the handful of women to ever join the Politburo, the most inner circle of Soviet leadership, and met Streltsolv at a ball held at the Kremlin early in 1957 to honor the victory of the national team at the Olympics.

Furtseva’s daughter, three years Streltsov’s junior, idolized the footballer and as children of party officials usually got their wish, Yekaterina approached him suggesting a possible marriage between the two. Streltsov told her that he already had a fiancée and would not marry her daughter and reports have stated that later on in the evening, whilst drunk he told Furtseva that he would never marry that monkey and that he’d rather be hanged.

Naturally, she was humiliated at such an affront to her daughter and Streltsov had made yet another enemy, this time one close to the big boss himself, Nikita Khrushchev. Streltsov thought his footballing prowess would protect him and make him immune to intrigue and politicking and anywhere else but the Soviet Union, that might have been true.

There were also unconfirmed rumours that Dynamo, the team of the police and KGB were out to get him, in a footballing transfer sense, as in many communist countries transfers of high-profile footballers were regulated through backroom politics. Whilst preparing for the upcoming 1958 World Cup, where the ‘Soviet Pele’ was due to meet his Brazilian counterpart, Streltsov ignored his imposed curfew to attend a party organized by Eduard Karakhanov, a military officer who had just returned from the far east.

Held at Karakhanov’s summer house or dacha, the party also featured Streltsov’s national teammates Mikhail Ogonkov and Boris Tatushin, who played for Spartak and a 20-year old woman named Marina Lebedeva. All three players would be arrested the next morning for allegedly assaulting Lebedeva. What follows is a recounting of various pieces of information, testimonies and stories relating to this case, ones that I was able to find on the Internet and ultimate judgement will not be passed on this occurrence.

The sensitivity of the subject and the seriousness of the allegations especially regarding a topic such as abuse by footballers, which has been at the forefront of recent scandals in the footballing world should not be taken lightly as well as the penchant of the Soviet administration for heavy handed scheming against the ones it perceived as a threat.

The Biggest Controversies in the History of the Champions League Final

The national team coach, Gavriil Kachalin immediately sprang into action, horrified at the accusations and the prospect of losing his best outfield player and went to the regional Communist party committee where he stated that his efforts to postpone the trial till after the World Cup were met with veiled suggestions that the order was coming from further upstairs.

Former national teammates defended Streltsov well into the future with some claiming involvement by the state and others pointing out that Streltsov and Lebedeva had been together that evening, but that all that happened was consensual. The matter of Lebedeva’s confession has been discussed at length and reports on it claim that it was riddled with inconsistencies, however many such reports that occur after traumatic events are inconsistent and often lead victims to not be taken seriously or cause their cases to fail and their abusers to walk free.

On the other hand, several pictures emerged of her bruised on a hospital bed and Streltsov’s face riddled with scratches in an apparent sign of struggle with someone. Streltsov’s supporters claim that these images were faked or represented injuries sustained later and unrelated to the case. Jonathan Wilson, who wrote an excellent article about this topic for The Guardian makes a very pertinent point that the Soviet justice system rarely required such cold hard evidence whenever it wanted to get a conviction.

Whether it was a true event that fell right into the laps of those who wished to see Streltsov dealt a serious lesson about following the regime’s ideals or a set-up, we will never know as most of the people involved in the case are either deceased or impossible to find. In light of recent cases of such nature involving players like Dani Alves, Mason Greenwood or Benjamin Mendy. I need to stress the importance of this case possibly being a one in a million occurrence where false allegations led to a wrongful conviction and not being presented from an apologetic point of view.

Any of you sitting there thinking that feminism causes men to be wrongfully accused and hordes of women looking to destroy footballer’s careers are just following players around hoping to get a chance to ruin their lives need to seek professional help or throw yourselves off a bridge. What is certain is that all three players arrested were at the centre of a very public trial and Streltsov is reported to have written a letter to his mother stating that he is taking the blame for someone else. Meanwhile, workers at the ZIL factory were planning protests in solidarity with Streltsov who they believed to be innocent.

Those planned protests were cut short when he admitted his guilt, reportedly being told by officials that doing so would ensure him receiving a slap on the wrist and maintaining his chances of taking part in the 1958 World Cup. Instead, he was sent to a forced labour camp, more commonly called a Gulag, and the two other players were served three-year bans and banned from representing the USSR for life.

In the camp, Streltsov received vicious beatings from another inmate resulting in a lengthy hospital stay and was later used by the camp’s commandants in football matches whenever they needed to calm down spirits amongst the inmates. In the meantime, the Soviet Union without Streltsov and his two teammates was severely weakened and lost to Sweden at the semi-final stage with the press writing that the two most weakened teams at that tournament were the USSR and England, who had suffered the Munich air disaster.

At Torpedo, another prodigy Gennadi Gusarov fired the team to a league and cup double in 1959 and several second-place finishes. In 1963, Streltsov’s 12-year sentence was cut short and he was allowed to return back to the ZIL factory and their amateur football team and started studying automotive engineering at the plant’s technical school. In the amateur factory league, he was a huge fish in a tiny pond leading his team to constant victories and when higher ups told the team manager not to include him in the squad at an away game, crowd riots forced the local factory chief to revert the order.

A change in Soviet leadership meant that Streltsov’s career received a fresh chance as Soviet chief Leonid Brezhnev allowed the player to return to professional football. In 1965, back at Torpedo he scored nearly one in two leading his side to another league title and regaining his place in the national team. His performances were somewhat blunted by the hardship of his years in the Gulag and he never won any trophies with the national side, who had become a powerhouse of European football during his time away, having won the 1960 Euros.

He won one last cup for Torpedo in 1968 before retiring two years later. After his retirement, he coached various youth sides of Torpedo before dying of throat cancer in 1990 at the age of 53. His first wife Alla, who had divorced him after his release maintained that the cause for the disease was the irradiated food which was served in the labour camp.

Marina Lebedeva’s later story is unknown and some reports have stated that she was seen laying flowers at Streltsov’s grave in 1997. After his death, and wishing to break with the perceived evils of the previous regime, Russia had to reanalyse the status of many former people sent to labour camps or executed and Streltsov was no different.

Luton Town Before the Premier League: Bonkers Presidents, Formula 1 Tracks and Pop Idol Managers

Streltsov currently has two statues of him in Moscow at the Luzhniki stadium and the Torpedo stadium, which is named in his honor and his face has appeared on a commemorative two ruble coin minted in 2010. Chess champion Anatoly Karpov led a campaign to clear Streltsov’s name, maintaining that a false conviction robbed Russia of its greatest-ever player.

The real truth of what happened at Karakhanov’s party will never be known and Streltsov’s will forever remain either a martyr highlighting the evils of the USSR or a criminal who got what he deserved, depending on which side of the story the viewer finds themselves on.

By: Eduard Holdis / @He_Ftbl

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / Getty Images