Football in the Eye of the Storm: The Beirut Derby

On February 26, 2017, thousands of passionate football fans in the Lebanese capital of Beirut strode towards the Tyre Stadium. In a country marred by political and religious tensions, football is a huge reprieve to the stressful lives of these football fanatics. However, this game they’re attending is no less of a clash of differing ideologies and dissimilar views.

On this February day, there were a few extra thousands that walked into the ground with fans taking up seats atop the floodlights and the stadium walls. There was a disaster in the works, a massacre waiting to happen, but for the fans of Al Ansar and Nejmeh, this was nothing new.

The scenes in the Tyre Stadium have been frequent – especially when these two teams are squaring off against each other. Ansar and Nejmeh are Lebanese football’s two most successful and prominent football clubs with a vast history going well before the years that were blemished by the civil war in the Middle Eastern country.

For many, the formation and subsequent rivalry between these two historical giants signified the birth of Lebanese football, and although there have been difficult times that have halted this famous clash, the two despise each other today just as much as they did just over 60 years ago when Nejmeh were born.

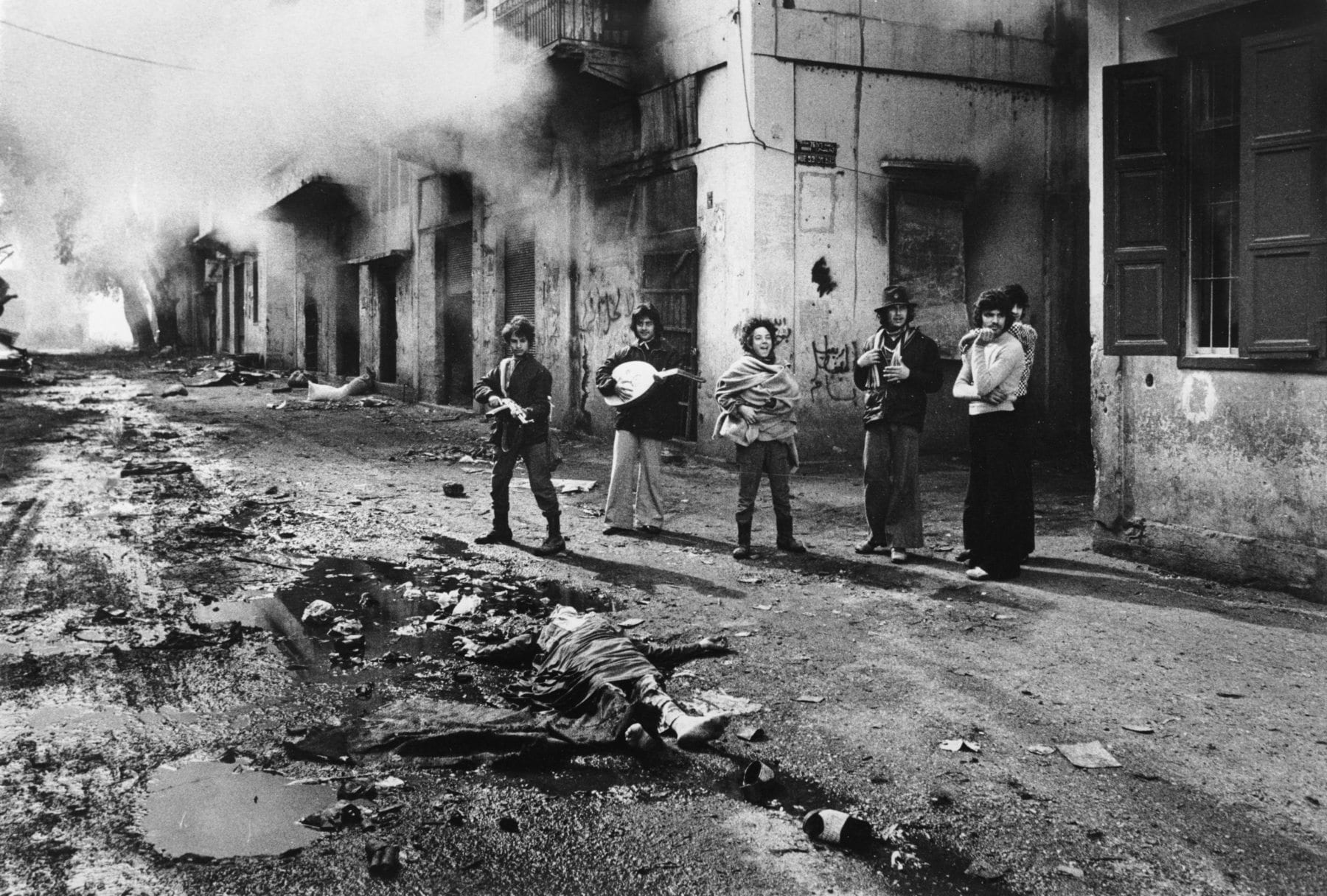

The country itself was a hotspot for tourists before the war broke out in the 1970s as its decent climate and exquisite architecture made for a worthwhile combination. But while that was what the Lebanese natives had eternally, there has always been divides in terms of politics and religion has always influenced almost daily aspects of tradition and culture.

Photo: Sunday Times

That has extended to football as well and it is why the hatred between Nejmeh and Ansar is so high. The two have alternating opinions and their history represents that which forms one of the most passionate, underrated derbies in world football.

Football started to pick up steam in Lebanon from early days. With many Armenian immigrants entering the country as well as the French picking up interests there, the sport started to grow in the late 1800s and the early 1900s.

The French gaining control of large parts of the country during the World War further aided the sport’s popularity in the Middle Eastern country and to this day, it is arguably still the country’s most loved game. And while the sport continued to grow, the people of power started to get involved in the hope of benefiting their political parties by appeasing the fans and giving clubs a religious identity that they themselves affiliate with.

Nejmeh, however, stayed away from that and made that clear in their formation years. Founded in 1943, they were mostly affiliated to the Shi’a branch of Muslims but on matchdays, they never made that clear. Although a majority of their following goes by the Shi’a followings, they are open to all faiths and are a welcoming club in the capital.

Most clubs in Lebanon mostly stick to the values of old, but Nejmeh has proven to be relatively progressive even in the modern day and when the time comes, all values are put to one side and all the focus is driven towards backing the strong burgundy that they sport.

Their rivals, Ansar, are mostly tied up with the Sunni Muslim fanbase and were born eight years after Nejmeh. Initially formed outside Beirut as the capital was already crowded with too many sports clubs, they set up shop in the south of the country, towards Mount Lebanon.

It wasn’t until 1965 when the capital’s population started to drastically rise that they decided to switch bases. Donning a vivid green colour on their shirt and crest, Ansar spent their early years in the second-tier of Lebanese football and it wasn’t until 1968 that they came to the top division, thus igniting the rivalry with Nejmeh.

Although the two clubs hold different religious and political ideologies, one common ground that they do hold is that the two fanbases are of the working class and there is no form of elitism that separates one group from the other.

The first clash in 1968 ended in a 2-1 win for Nejmeh, also known as ‘The Lighthouse Men’, and it was from there that the two sides saw their popularity grow, albeit not just in Beirut. They both would tour around the country, playing in Tyre, one of the southernmost regions in Lebanon, as well as Tripoli, one of the northern-most. At this point, many felt that Lebanon, aided by these two clubs, could rise to one of Asia’s finest footballing nations.

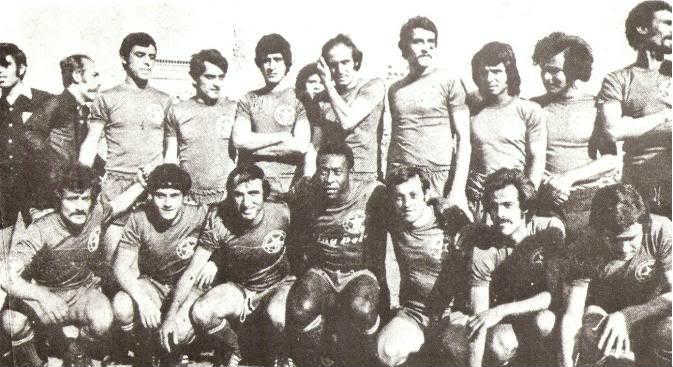

Around the 1970s, Lebanese football was dominated by Nejmeh. This was a magnificent era for the club as they rose to become the country’s most popular team, drawing in fans from all corners and feeding them with success and silverware.

Photo: AbdoGedeon

Having won the league in 1975, the legendary Pelé even arranged a friendly to play for them and over 50,000 fans attended. This game, however, only postponed one of the most heinous phases in Lebanese history. It was just a week later that the fun would stop as a bus shooting in the capital would take place that would signal the start of the long, drawn-out and bloody civil war.

Between 1975 to 1990, football was strongly limited in the country due to the violence and by the time it could return, the interest also suffered. Towards the end of the fighting, Ansar also won their first league title in 1988 and they wouldn’t stop there.

They would go on to win the league 10 more times in succession, setting a world record in the process and quickly becoming the country’s most successful outfit. This angered those tied with Nejmeh as they believed that their rivals’ success was largely due to bias from the FA and support from prominent financial backer, Rafic Hariri – a billionaire who was running to become the Prime Minister.

The post-war success for the green of Ansar was vast and in a country that had already been embroiled in great corruption over the years, Nejmeh’s crying calls against their bitter enemies would only echo away and eventually die. It was around this time that the rivalry would reach boiling point.

On one side of the city, there was a team reveling in their success with seemingly no one capable of stopping them and on the other, there was a team that knew they had the potential to stop the superpower but felt powerless themselves due to the strength of the opposition – a strength which wasn’t limited just to the football pitch.

But while Nejmeh cried foul over their rivals, it could be said that they had this coming. The club was undergoing vast changes at the time of Ansar’s success – changes which were often negatively affecting them. Poor recruitment, an aging team and frequent quarrels between top tiers of the club’s management wasn’t doing them any good and the results on the pitch were evident of that.

The club were a far cry from the machines they once were, but they still refused to accept that it was the internal management that was dragging the club through dirt. Their fans would take to the streets in the hope of getting government intervention to support them, but this was to no avail.

Despite the contrasting fortunes of the two clubs, matches between them during Ansar’s golden period in the 1990s were still great. In the 1992-93 season, Nejmeh managed to get the better of Ansar with a 2-1 win on away turf.

This win was particularly significant as Ansar were on a 91-match, 18-year unbeaten streak – a run which was largely aided due to competition stopping because of the civil war taking place. The result, however, had no implications on the final standings in the league. The Green Boss, as they were known, ended up winning the title with a nine-point advantage and got revenge on Nejmeh’s turf, winning the reverse fixture 3-0.

A Trinidadian who went by the name of Errol McFarlane is also an important figure in the history of these two sides. The forward had four separate stints in Lebanon – three of them for Nejmeh – but his time in the country between 1999 and 2001 was the most significant.

Photo: SocaWarriors / Shaun Fuentes – TTFF

With Ansar dominating, McFarlane would be the spark Nejmeh needed to boost themselves and in the 1999-00 season, he would score a stunning diving header against their rivals. That results spurred the Lighthouse Men as they went on to break Ansar’s 11-season monopoly over the league title and be crowned the champions of the Lebanese Premier League.

This was generally a good phase for Lebanese football. Not only was the competition between its two most successful and popular teams becoming stronger, they were also awarded the rights to host the Asian Cup in 2000 – a major achievement considering that the war had ended a mere decade prior.

The arrival of international fans and potential investors meant that interest in Lebanese football grew and after a relatively enjoyable tournament, the higher-ups in the country ensured that the top-flight would be given greater attention. However, while this was certainly positive, it took an adverse effect on Nejmeh.

As clubs around them grew, Nejmeh were unable to keep up with the frantic changes and went through a period of instability themselves. They managed to break the Ansar stranglehold on the top-flight and stayed on top until around 2005, adding three more league titles to the one won in 2000 as well as five Lebanese Elite Cups in what was a fine time for them.

However, that all changed when Omar Ghandour, President of the club for over 30 years, recognized that his team was going in the wrong direction and decided to leave. It was soon after his departure that they club would once again suffer losses and see disputes divide the boardroom.

Contrastingly, Ansar were on the way up. After going through a period of uncertainty themselves, they appointed Rafic Hariri, one of the wealthiest men in the country as well as its Prime Minister as the club’s new owner.

This had two effects on Lebanese football, and they come as no surprises. First, Nejmeh would see their records dwindle and second, Ansar would be back on the rise. The Green Leader would also improve their playing facilities by renovating and increasing the size of their Al Manara Stadium and at this point, it seemed as though they would create another dynasty in the Lebanese top flight.

Alas, there was another twist in the tale. In February 2005, Hariri was assassinated when around 1,400 kilograms of TNT that was concealed in a van exploded as his motorcade drove through Beirut. 22 men including Hariri himself were killed in the plot, but the long-term harm would be much more.

Photo: AFP

As a tribute, Al Ansar changed the name of their venue from the Manara Stadium to the Rafic Hariri Stadium – a fitting acknowledgement to a man that had done so much for the club he deeply loved and could well have done so much more. This would signal the start of another period of turmoil as the aftermath of the assassination would wreak havoc all over the country.

Terrorism started to become rife, the football was often postponed, and the division caused by differing religious and political views would cause problems in the stands. Just when there was hope that football would see a positive light in the country again, all the momentum was lost, and this just became another sorry, violent period in the region.

The war went international and football was just consumed in the fracas. In the middle of it all, an attempt was made at reducing the violence in the country and fans were banned from entering stadiums. This was now getting ugly.

By the time the sport resumed, the scene had changed. Old rivals Nejmeh and Ansar, the two most dominant forces in the country were often taking the backseat to the politically and financially-driven Al Safa, powered by Druze community, and Al Ahed, supported by Hezbollah. Interest has dried out as well and the statistics are there to prove it.

At its peak, the derby used to average about 50,000 fans per game, but that has gone down to around 20,000 in the current day. Still the most popular fixture on the Lebanese football calendar, one can only wonder how much potential the clash would carry domestically and internationally had it not been hit so hard by the sad situation.

The men involved behind the football have killed the sport as well. The match fixing issues of 2014 which harmed the national team, where two players received lifetime bans from the sport and 22 others were banned temporarily only added further fuel to the fire, and that has killed a historic rivalry.

Despite the fascinating attractions of watching great European teams play, there are still some groups in Lebanon that love watching their local teams, and for that reason, a six-point plan was drawn up in 2017 to support the domestic division. One must have to wait to see if these plans can have a positive impact because as of now, things look difficult.

The transitions in the history of this fixture have been tragic. What started as a difference in ideology got interrupted by rogue politicians, officials and referees and that has only tarnished the legacy of an iconic clash. When these two teams meet, it’s still passionate, it’s still intense and it brings out the best in the fans and players, however, the current day should be offering so much more.

This fixture is a shining light, not only for Lebanon, but also for the Middle East as it shows how important football is to the local culture and society. When it was good, it was very good, and one can only hope that it gets to that level once again sooner rather than later.

By: Karan Tejwani

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / The AFC

This article was originally published on Football Chronicle.