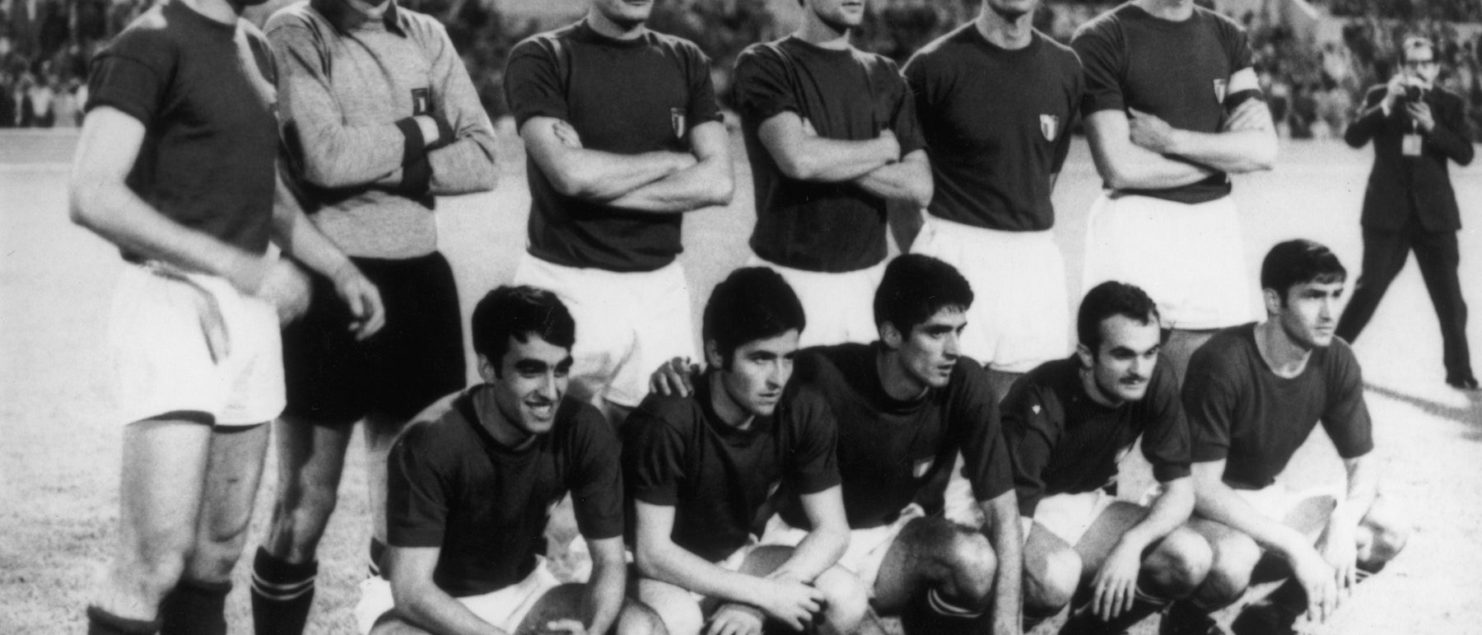

UEFA Euro 1968: Italy’s first and only European triumph

As we get set for another couple of rounds of qualifying for the Euro 2020 finals, and Italy prepare to face Armenia and Finland, time to look back at the first, and so far, only time the Azzurri were European champions.

The pre-cursor to what is now known as the European Championships, was the Central European Championship that occurred during the late 20’s and throughout the 30’s. Italy won the tournament twice and were runners up twice as well. It came during a period when the team from the peninsula dominated world football, as they also achieved back to back World Cup wins during the same period.

The modern day version of the tournament was taking place for the third time in 1968 and Italy were the designated hosts. Unlike recent finals, that one took the format whereby the teams on the continent would play a qualifying phase before a final phase of four teams played on a strictly knock out format, of two semi-finals and a final.

Besides the hosts Italy, the other nations to qualify for the Finals were the then World champions England and hugely talented Yugoslavia and Soviet Union teams. What a line-up!

Back then things were much different then there are now, as there were no coloured televisions, no penalty shoot-outs and both semi-finals took place on the same day.

The last four took place on the 5th of June with The Azzurri facing the Soviet Union at the Stadio San Paolo in Naples, while just over three hours later, saw Yugoslavia taking on England at the Stadio Communale in Florence.

In one of the very few matches that they were in the same starting 11, Gianni Rivera and Sandro Mazzola started controlling the tempo of the match from the onset in rainy conditions in Campania. However, after a clash with Soviet player Valentin Afonin, Milan man Rivera was forced off the field following the incident.

Despite the conditions, both teams created chances; Piero Prati shot just wide from inside the box for Italy, while the Soviet team forced Azzurri goalkeeper Dino Zoff into some solid saves.

After 90 minutes however, the teams were deadlocked and they headed to extra-time.

In the added 30 minutes, the best chance fell to the home team, as Inter player Angelo Domenghini hit the woodwork and the closer the game got to the end, the less both teams pushed forward. They were wary of being left exposed to a fatal concession of a goal that would have left them out of the final.

The extra-time period also ended scoreless, so a winner was needed to be determined in an unusual way. Unlike what we seem to have at all major footballing extravaganzas in the last few decades, back then, a penalty shoot-out was not part of the game, so a place in the final was to be decided by, get this, a toss of a coin!

People talk a lot about luck in sport, and this was one such occasion that it would definitely play a bigger part than normal.

The scenario saw Azzurri skipper Giacinto Facchetti and his opposite number Albert Shesternev, accompanied by the referee and two administrators from the two countries go into a separate room for the coin toss. The Inter attacking left-back called tails and fortunately for him, it was the right call as it landed on said tails. After winning the coin toss, Facchetti said “It was the right call and Italy were through to the final. I went racing upstairs as the stadium was still full and about 70000 fans were still waiting to hear the result. My celebrations told them they could celebrate an Italian victory.”

The other semi-final was dramatic as well, with Yugoslavia grabbing an 86th minute winner through Dragan Dzajic to get past England in Tuscany. So the grand final was set and it would be hosts Italy versus the Balkan nation played at the Stadio Olympico in Rome.

If the semi with the Soviets was rife with drama and intrigued, the final was as well, although this was decided entirely on the field of play rather than in a private room.

The final kicked off at a rather late time of 10:15 pm with both teams much changed from their previous semi-final encounters.

Yugoslavia were the much fresher, quicker and overall better side in the final and they duly took the lead through Dzagic late on in the first half, as he scrambled the ball past Zoff after neat build up play. The tension from the home crowd was palpable as the teams headed to the interval.

However, Italy came out in the second half and pushed for the equaliser as if their lives depended on it and were rewarded in the 80th minute. The hosts won a free-kick just outside the box and Domenghini drove the ball past everyone and it rattled the net and the final was tied. The sense of relief from the tifosi in the Eternal City was obvious.

During the additional 30 minutes of play, the Balkan nation had two guilt edge opportunities to take home the title, but some last gasp defending and goalkeeping from the now legendary Italian rearguard kept them out. After full time of extra-time, the teams could not be separated at that point.

It meant a reply was required which took place just two days later…

The Azzurri were able to recall the likes of Mazzola and star striker Luigi Riva to their starting line-up and it paid dividends. Unlike the first final that was mostly dominated by the Slavs, it was Italy that would control this match from start to finish.

Cagliari’s Riva who was returning from a broken leg, an ailment that would affect his entire carear made a huge impact, as his physical presence and ability to link well with his teammates caused the opposition all kinds of headaches.

He could have so easily had a beaver-trick at the final, as his rustiness showed…He missed three glorious chances from a header, a close range shot that was a saved and a volley that he hit over the bar from a goalkeeping error. Eventually he did put one of those opportunities away, as a miscued shot from Domenghini found it’s way to him and he swiveled and hit a left footed effort into the far corner.

Italy finally had the lead their play deserved and they would not let up.

An often overlooked past great of Italy is Pietro Anastasi, but the Sicilian was arguably the team’s best player in the final.Probably his best moment in his carear came at the 30th minute mark at this final, with a quite spectacular strike. The Catania born player was at Varese at the time, but his performances that year, including a hat-trick versus Juventus in his team’s 5-0 win, earned him a world record move to La Vecchia Signora.

He collected a pass from Giancarlo De Sisti, he flicked up the ball and blasted the volley into the goal that gave Illija Pantelic no chance in the Yugoslav’s goal.

Italy’s opponents were clearly not up for the fight and the home team created several chances in the remaining hour of the final, and while they failed to convert, the trophy was their’s.

Facchetti gladly accepted the Henri Delaunay trophy and lifted it high into the Roman night as his nation claimed the UEFA European Championship for the first time. By the time next year’s Euro 2020 roles around, it would have been 52 years since that maiden and single triumph for Italy at the Euros.

So far under Roberto Mancini, this generation of Italian players are dreaming of ending that long drought and given a solid start to their qualifiers so far, they may just be the squad to end the “curse.”

By: Vijay Rahaman