26 years on: The Vindication of the Back-Pass Rule

1992.

The balance between the 1990 World Cup and the 1992 Euros emits a sense of annoyance and apathy in the general public. The languid 1992 Euros gives the necessary push to the International Board to change the rule of passing back to the goalkeeper, in spite of the skepticism of many. Still, a change is not truly a change if it is not met with rejection at first.

The main spokesmen of this resistance are the goalkeepers, who begin to demonstrate their disgust through several different means.

The Valencian goalkeeper Jose Manuel Sempere would say “We are goalkeepers, not players.”

“It will provoke the save, in general,” as Juanmi, Real Madrid’s goalkeeper, would say. Like his coach Benito Floro said, “don’t complicate life.”

These first few years would not be simple at all for the players closest to the penalty box. Ironically, the ball would represent a problem, and the back pass a condemnation. Many agreed with the analysis, such as the Basque Jose Manuel Ochotorena, then goalkeeper at Tenerife, who said that the new rule forced the long ball, provoking even more anti-football.

The famous English goalkeeping coach Alan Hodkinson said that the new rule made goalkeepers look like idiots and he asked, is this good for football?

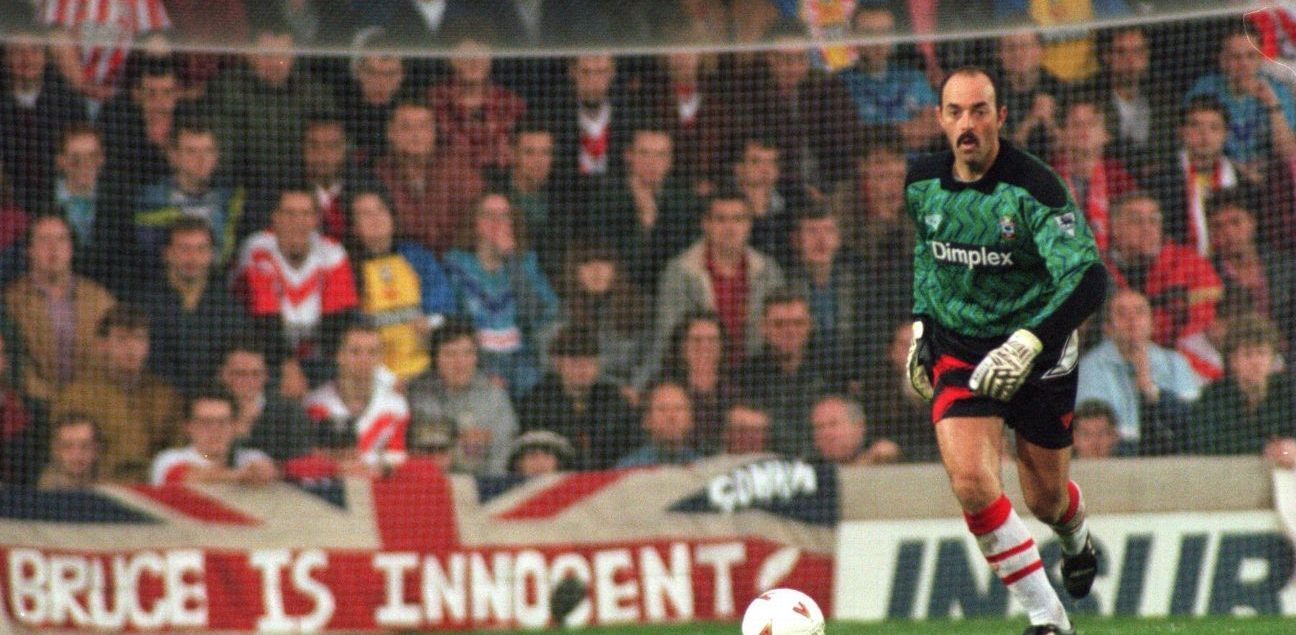

During the first years after this rule change, there were many notable mistakes amongst defenders which would leave the goalkeepers exposed, but there were also iconic situations such as this great save from Coupet after a failed back pass.

Even the referees joined in the protest. Like Neil Midgley, the referee spokesman, complained: “Adding extra tasks makes our job even more difficult.”

The new rule would bring much confusion to referees tasked with judging the intentionality of the back pass, to interpret whether or not the goalkeeper would be allowed to pick up the ball with hands.

In contrast to these pessimistic naysayers, there would be many other people who began to see how this rule change would transform the game of football as we know it. One of them was the English journalist Guy Hodgson who opined that after the rule change, the goalkeeper would ideally become the launching point of an attack, or worst case scenario, a laughingstock.

Obviously, the English writer omitted the fact that the goalkeeper has always been the launching point of the attack. However, the goalkeepers who boasted an impressive ability to play with their feet were a minority, due to the inertia of tradition. In the case of Real Madrid’s Rogelio Dominguez, or Manchester United’s Ray Wood in the ‘50s, these goalkeepers were capable of sending an accurate long pass to the fullback. Or Amadeo Carrizo, or later on, Hugo Gatti or Rene Higuita. These men were pioneers of the goalkeeper position.

Obviously, with the rule change, the goalkeepers became more exposed to errors. After all, they no longer had the emergency option of picking the ball up with their hands in response to any minor inconvenience. Franks Hoek, the famous Dutch goalkeeping coach talked about the goalkeeper’s adaptation to the game’s changes. But this adaptation would take time, as most goalkeepers did not have the necessary technique to be a reliable source of distribution from the base of play. In fact, it was not uncommon to see field players take goal kicks.

While there would be teams that would look to develop play from the back, whenever they were faced with any pressure whatsoever, they gave up their initial ideas and played long balls, hoping to gain a lucky ricochet in an attempt to lay siege to the opponent’s goal.

The vast majority of these long balls would not be the fault of the goalkeepers. Instead, the players closest to the goalkeeper did not offer themselves up as passing options. Simply put, it was not in the game plan.

And even if it was in the game plan, the players did not place themselves in an ideal position to give their goalkeeper the passing option. We saw this in the case of Arsenal, where a player blocks the passing lane between the goalkeeper and the center back, or in the case of Valencia, where the RCB positions himself too centrally so he cannot evade the rival’s pressure.

Or in other cases, the defenders paid too much attention to the rival forwards, as they attempted to escape their close marking. This attempt to play short, both intentional and playful, which gives sequential advantages to each player, functions through a harmonious amalgam between the spatial-temporal location of deception and technique. When one of these three components is not or is in scarce condition, the attack does not flourish, like in Euro ‘96, when Spain and Romania faced off against each other, and the keeper gave the ball away. Or, in the game between Inter and Schalke in 1997, where the build-up is free from pressure, yet the defender still decides to play the long ball, giving the ball away to the opposition.

Nonetheless, there would be coaches like Johan Cruyff who aimed to attack from the base. The first lines of attack needed to be involved in the construction of play, offering continuity to the game and allowing players to receive in positions for them to penetrate opposition lines.

These first few years were marked by the ideas of ex-goalkeeper and Argentine coach Ricardo La Volpe. LaVolpe lined up three central players in the first line of Atlante, who won the Liga MX title in 1993, in order to generate numerical superiority against two strikers. This was the famous “salida LaVolpiana,” which won over a fan in Barcelona’s Pep Guardiola.

Another team that would make a similar build-up proposal was Xabier Azkagorta’s Bolivian national team, which played in the 1994 World Cup. In this three-man back line, Quinteros would find a free man while behind the line of pressure, while Melgar drifted to distribute from inside. It was with this system that Bolivia faced the defending world champions in Germany. Bolivia player a great game with moments of remarkable dominance on the rival’s half of the pitch, recovering quickly to stay compact, and daringly messing with the German resistance.

Although they would be eliminated in the first round, this team would rebel against ancient paradigms that solely correlated beautiful football with world class players. The pressure on the goal kick was unusual: the majority of teams allowed the rival to build from the back, and win back the ball when they found an opening.

Against the slightest pressure, the majority of teams chose to not complicate their lives, as Benito Floro said. Few teams would seek to play out of the back right from the goal kick.

Juan Manuel Lillo’s Salamanca, in an attempt to advance to the Primera, would demonstrate a different kind of build-up, forcing the team and the ball to move together. One of the defenders would pretend to receive from the goal, liberating the zone of opponents, so he could find passing options (other CBs) on each side of the first line. This new type of build-up gained popularity amongst teams, and Barcelona would practice it years later, even against Lillo’s Real Oviedo.

In 1995 and 1996, it was Real Madrid, managed by Jorge Valdano and Ángel Cappa, who would show some samples of build-up while under pressure. This is an example against Atlético de Madrid, where they climbed step by step as the players stagger themselves on different levels, until they finally reached the opposition’s penalty box.

Another great team of this era would be Louis Van Gaal’s Ajax, who won the Champions League while playing brave and attractive football; the ball went to the position, and not the opposite. The Dutch team took its daring plan against both low and high pressure, where they would bashfully play out from the back, in order to slip away from pressure and attack space in the other half of the pitch.

On the other side of the pond, Marcelo Bielsa took charge of the Argentine national team in 1998. The Rosario coach’s teams showed that they could build its way out from the first line of attack, and to then provide the depth needed to then make use of the generated spaces up front.

It was more frequent to see matches where the players relied on both the goalkeeper and the defenders (also formed in 3-man backline) in order to find the spaces to move the ball vertically, by slipping away from defenders and finding an opening towards the wings.

Another team that left its mark in the late ‘90s was Dick Advocaat’s Rangers. It was a team with honorable respect for the ball, a respect derived from the old scrapbook of legendary Scottish football. From the penalty area, the team created overloads on the wings and used the third man as a dissuasive weapon.

In 1999, Rangers scored a legendary goal against Borussia Dortmund, demonstrating that the pass back could be used as a tool to further elaborate an improved attack, forming triangles through the pitch to reject any type of pressure, disorganizing in the final third to unleash attacks.

In any case, this form of play was not normal. More often, teams played a more direct style based on long balls and aerial balls.

And although this style seemed more defensively secure, it had its disadvantages. The long ball can safeguard a team from danger, but other times, it can only endanger them even more. One famous episode of this was in the 2002 World Cup Final, where Oliver Kahn played a long ball, with his team stretched forward, allowing Brazil to take advantage of the spaces and seal their World Cup victory.

One team that epitomized this mix of styles was the 2002 South Korean World Cup semi-finalists, coached by another Dutch manager, Guus Hiddink. This team alternated between direct long balls from the goal to their forwards, to intricate play between three footballers, where the holding midfielder drops between the two center backs to generate a numerical superiority: 3 defenders vs strikers. 2. By doing this, they drag one of the opposing forwards out of position, change the orientation with the center back on the rival’s weak side, and from there, the CB can drive forward, unmarked, and play a pass into the forward once an opposing player closes him down.

In this goal kick, one can see how the center backs retreat to build from the back with the “mediocentro,” despite initially pretending that they would play it long. They begin playing out from the back with the goalkeeper, faced with the improbability of progressing. The attack is interrupted when the players cannot find a free man to pass to, to continue their progression towards the opponents’ goal, and thus, they make the direct, long ball.

Despite this trend of playing it long, Arsène Wenger’s Arsenal appeared as a counter-cultural case in English football. Through their build-up through their fullbacks, and their link-up with the third man, they crushed their rivals and even won the Premier League without losing a single game in 2004.

In 2004, in Perú’s Copa América, there was an atypical game for the era. Marcelo Bielsa’s Argentina faced off against Ricardo La Volpe’s Mexico. It was atypical because both teams would attempt to press high up and interfere with each team’s build-up play. Mexico, with a 3-man back line, used the third CB as an indispensable tool to build from the back. Argentina, on the other hand, went with two center backs, with Mascherano occasionally dropping back to assist the build-up, and with Bielsa’s trademark frantic pace on the wings troubling Mexico.

Mexico won, but football changed forever after this game.

In 2007, Pep Guardiola was hired as Barcelona B’s new coach. The revolution was set in motion: Guardiola rescued old ideas from the dead, mixed them in just the right doses, and adapted them to the 21st century. The ideas of Hogan, Sebes, Cruyff, Menotti, Lillo, La Volpe, Bielsa, and many more, were adapted in Pep’s plans.

During this first year, Pep would implement several minute details in the build-up that would make Barcelona B immune to any sort of pressure.

The center backs lined up almost parallel to the keeper in the goal kick, with Sergio Busquets between the center backs generating superiority, with the interiors ascending or descending into the middle spaces depending on the opposition’s defensive organization. With the ball retention to pull in the opposition out of their own half, with defenders evading their markers to find a free man open, with fullbacks dribbling their way out of pressure, with the patience to retreat and overload the wings, and then switch play to the open wings, Barcelona B played beautiful football en route to their successful promotion under Guardiola.

In summary, a concert of fabulous movements, an orchestral team, full of ideas and harmony, and above all, a team united by a common passion for the ball–this is the main reason why football is still the game we know and love today.

By: Zach Lowy

Photo: Chris Cole/ALLSPORT