Liverpool’s 4-3-3 vs. Liverpool’s 4-2-3-1

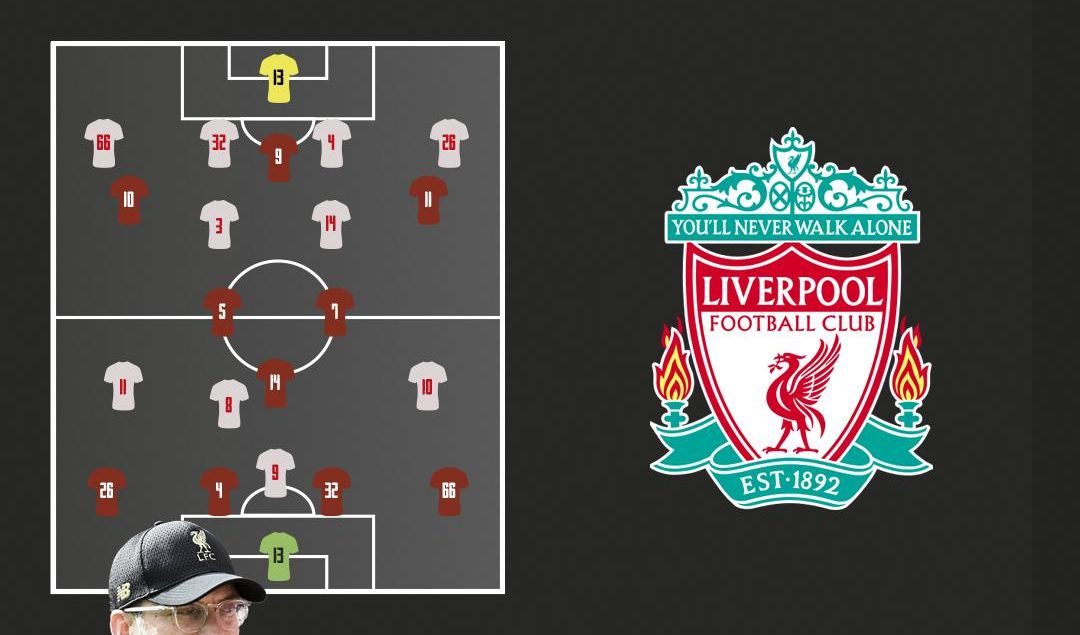

Liverpool’s 4-2-3-1 is a defence-first system that’s typically utilized against teams that Jürgen Klopp feels Liverpool have a clear quality advantage against. It’s designed to increase the compactness of the team from the moment the ball is lost. The essence of the system is the strong central spine. The two key elements within the system revolve around the first and second phase in which the ball is lost.

The first phase in which Liverpool lose possession of the ball is known as the counterpressing phase. This is where Liverpool look to win the ball back as quickly as possible. Because Liverpool utilize this system against inferior opposition, the ball is most often won back via this method because the opposition lack the quality to retain possession under pressure. Liverpool’s forwards are often in close proximity because of the spacing dynamics within the system, and this enables effective pressing as soon as the ball is lost because lots of players can surround the ball carrier quickly in groups.

Liverpool’s primary pressing feature revolves around defensive overloads on the byline. They encourage a pass to the fullback, before the wide midfielder presses him and the rest of the team shuttles across to close down the space on that side of the pitch as seen in the image below. This leaves the fullback with the choice to pass centrally to the tightly marked midfielder, recycle to the centre back or goalkeeper who’s also under severe pressure and has limited passing angles, or hook the ball in a general direction down the line.

Other ways that Liverpool press include situational man-oriented pressing, in which the players press as a unit when one player triggers the press by deciding to close down a man in possession, a loose ball, or if he reads where the player’s next pass is headed.

The second phase of Liverpool’s defensive transitions revolve around the midfielders in the double pivot. They form a central defensive quartet with center backs, and between the four of them, they stifle transitions quickly if the initial counterpressing phase is bypassed.

As shown in the image below, Liverpool’s two deep-lying midfielders are generally positioned in this zone and look to nullify any transitional threat, whether it be winning second balls when the opposition pump the ball forward in a direct manner or if a player is dribbling at them. Fabinho in particular is outstanding at dominating his zone. It’s rare that teams get past Liverpool’s initial counterpress, let alone the triumvirate of Fabinho, Georginio Wijnaldum and Jordan Henderson. They all possess top positional discipline and understand Klopp’s requirements incredibly well.

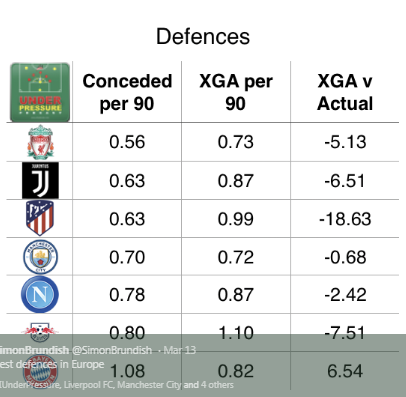

Liverpool are, according to certain statistics, the best defensive team in Europe. This is a result of Klopp knowing which system is the most efficient to use depending on the opposition faced. The 4-2-3-1 is largely utilized because of its counterpressing prowess but also because of the central defensive quartet. However, the settled shape in that system isn’t as solid as it is in the 4-3-3, which is why Klopp reverts to that system against superior opposition.

Liverpool’s settled shape is rarely tested against inferior opposition because they don’t have the quality to play out of Liverpool’s press, but also because teams generally look to play quick, transitional football against Liverpool because it’s unlikely they’ll match the team possession-wise, but even if they do, they’re playing into Liverpool’s press.

One player who hasn’t met the lofty expectations attached to a transfer fee of £52.75 million is Naby Keïta, and that’s largely down to his inability to adapt to Klopp’s defence-first system. The player himself has good defensive statistics, but that doesn’t tell the whole story. Keïta constantly looks to press the ball carrier because of his all-action style. He doesn’t understand the importance of blocking space, particularly as a double pivot player, in Liverpool’s off-the-ball shape. A prime example of this is when he came off the bench vs. Burnley.

The Burnley player received the ball in central midfield and Keïta aimlessly wandered out of his defensive zone towards the ball carrier. Fabinho remained in his zone however, and was left outnumbered centrally because Keïta vacated the left half space, leaving a Burnley player with time and space to receive between the lines. Liverpool conceded a goal as a result of this.

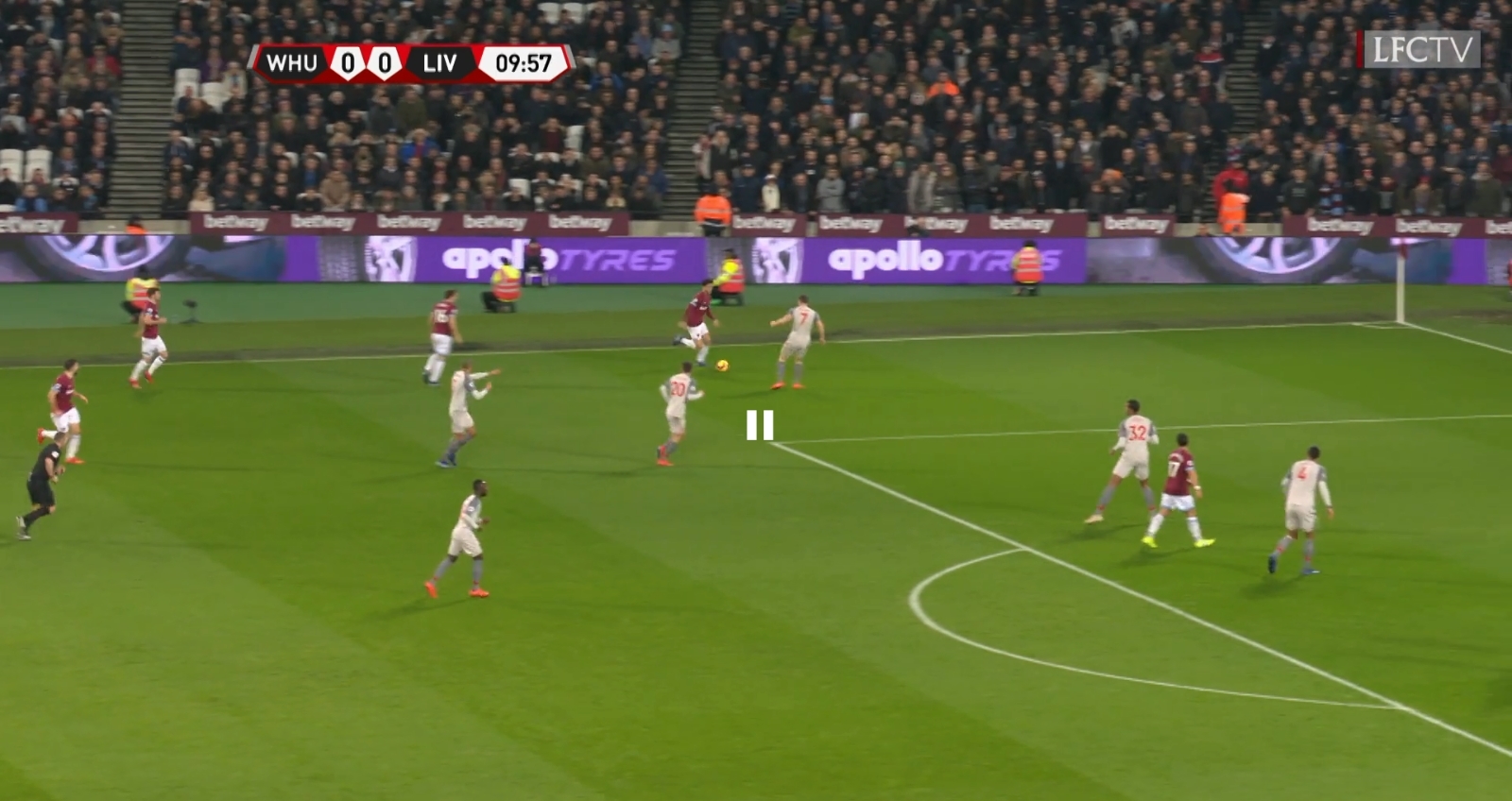

A key player for Liverpool’s defensive transitions and pressing game is Wijnaldum – his influence isn’t always reflected on the stat sheet, but without him, the team struggled against West Ham, Everton and Burnley. The Dutchman makes the whole team more compact by positioning himself alongside the defensive midfielder at all times resulting in a more effective counterpress. As a result, there are fewer passing lanes open and Liverpool boast a stabler defensive transitional phase, with an extra central defensive midfield player in transition.

Liverpool’s other second phase midfielders (Keïta and James Milner) don’t possess this defensive discipline as they roam outside the lines and look to interchange in the final third too much. Wijnaldum is a key tactical weapon for Klopp.

Spacing/possession play

In Liverpool’s build-up in the 4-2-3-1, the players in the double pivot receive outside the lines or centrally. The fullbacks are free to position themselves high on the flank or slightly ahead of their nearest CB partner. It’s far more fluid than a team like City, who are more structured in that regard but are allowed to be because of their elite technicians.

Whereas City will sacrifice a player in the build-up phase to maintain numerical advantage in another phase, Liverpool aren’t as accomplished in the first phase, so they need two midfielders as opposed to one. They also play a double pivot for extra central cover in case the ball is lost because the positional play compared to City isn’t as good. Liverpool is worse in possession, so they need to be more wary of defensive transitional situations.

The primary form of chance creation within the system is counterpressing, but that’s not always the method utilized because of how teams set up against Liverpool. When teams don’t play into Liverpool’s hands by trying to play out from the back, Liverpool are tasked with breaking them down.

In order to break down a deep block, you must have good spacing, where players find themselves in close proximity between the lines, and with someone moving wide to stretch the defense, so as to maintain even distribution of key spaces. You must have composure and patience, circulating possession as opposed to pumping balls into the box. Most of all, you must have ball retention in and around the box, which increases the defenders’ mental and physical fatigue because they constantly have to deal with high pressure situations.

Liverpool are solid in all of these regards. Their chance creation isn’t as relentless as a team like Manchester City but their spacing is still good. The team creates enough chances, situations (as Klopp likes to call them) and goal threats to win games.

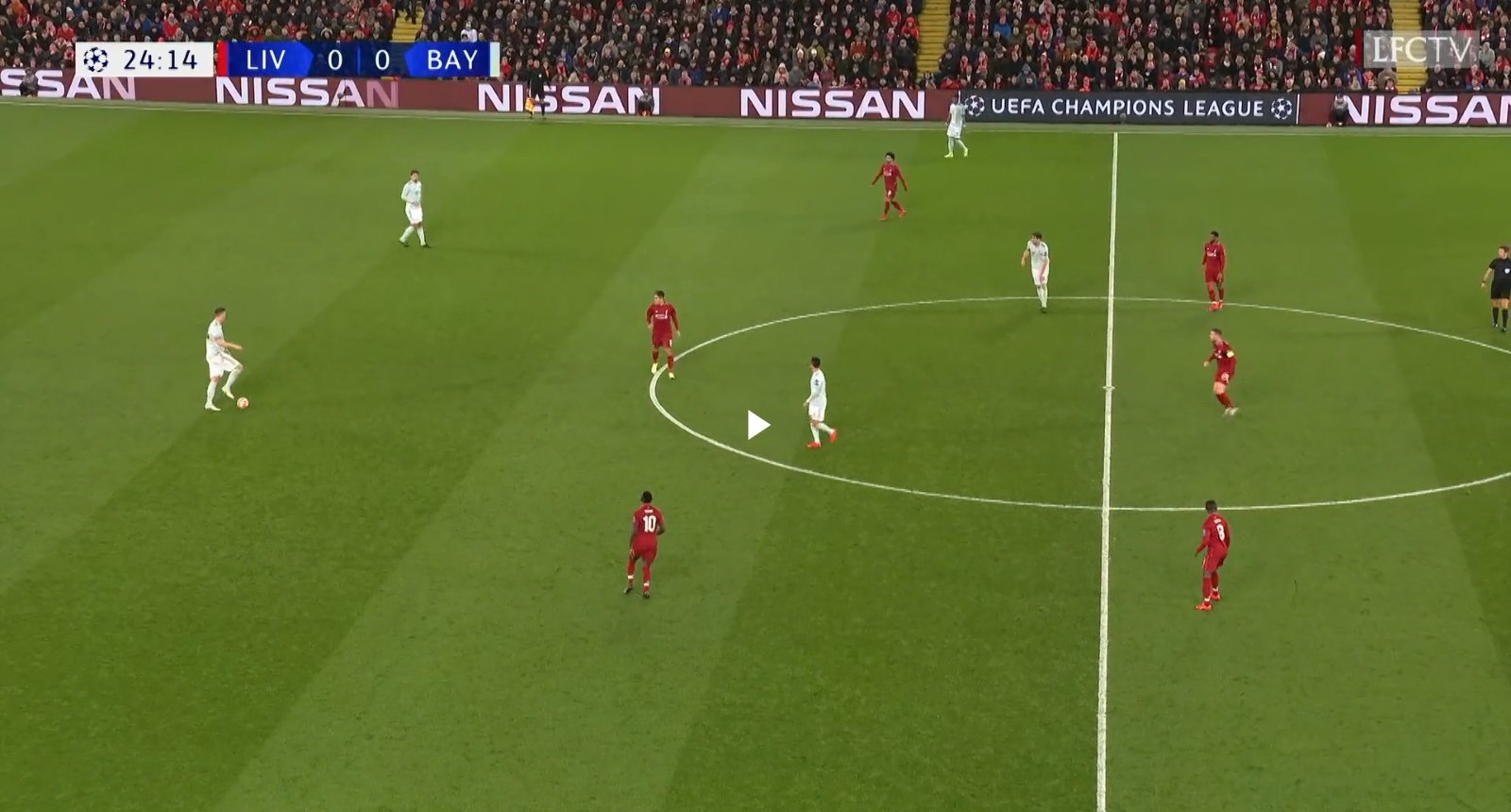

As seen in the image above, Liverpool focus on using the fullbacks as the wide outlets whilst utilizing the wide midfielders as attackers in the half-spaces. Roberto Firmino is the #10 and he will play between the lines while Mohamed Salah will look to run beyond the last line of defence. However, because of the fluidity the attackers are afforded, the reigning Golden Boot winner regularly combines between the lines too.

This is a good attacking structure as it enables vertical progression (players between the lines), combination play (attackers in close proximity), the ability to counterpress efficiently (attackers in close proximity to press collectively) and unpredictability (the fluidity afforded in attack with players constantly interchanging).

Liverpool’s 4-3-3

Liverpool’s 4-3-3 is a counterpressing-orientated system, just like the 4-2-3-1. However, the counterpressing is more calculated better timed because Klopp primarily uses this system against higher quality opposition. Because the 4-3-3 is the ‘big game system,’ Liverpool focus less on having the ball and creating via things like spacing because the press and offensive transitions is the main form of chance creation. However, Klopp has changed to the 4-3-3 for the run-in in his pursuit for domestic and European glory regardless of the opposition. This could be due to the pitch size or the return of Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain and Adam Lallana, who are more suited to playing as 3rd CMs as opposed to wide players in the 4-2-3-1.

To those who laugh when I say Klopp has reverted back to his primary system of the 4-3-3 for the remainder of the season due to pitch size, I say this: do not underestimate the attention to detail of a man who hired a professional throw-in coach. Liverpool have a clear statistical advantage on smaller pitches because it’s easier to condense space in a smaller zone. As such, it’s easier for Liverpool to press on a smaller pitch.

Over the last 2 seasons, Liverpool average 1.33 points per game on pitches bigger than 7000sqm. On smaller pitches, they average 2.6 points per game. Anfield is 6868sqm. Of the remaining 6 away games, 5 are on pitches smaller than Anfield and Southampton is 6936 (@SimonBrundish on Twitter 1/3/2019).

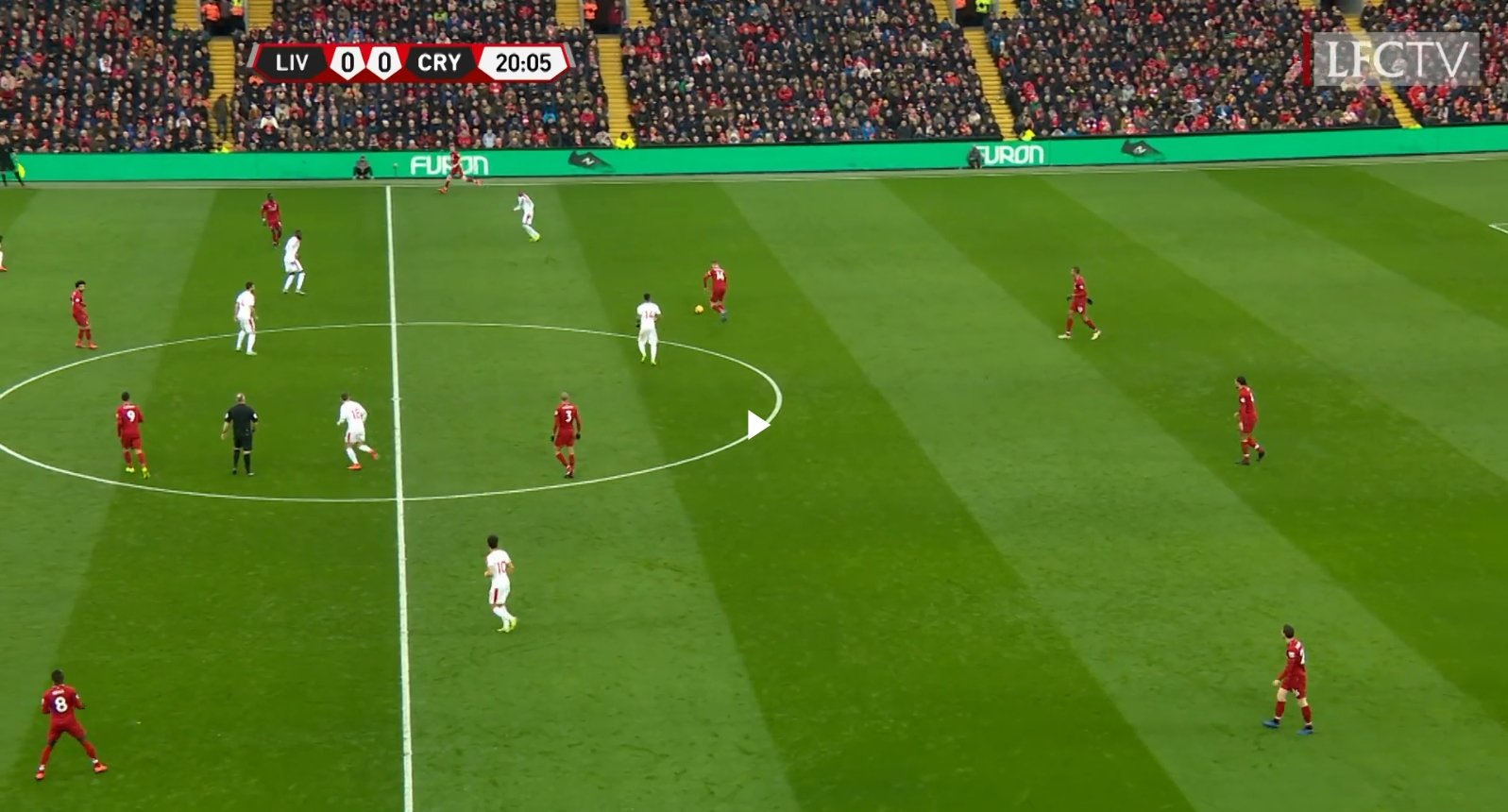

Liverpool’s press is more calculated in the 4-3-3. Salah-Firmino-Mané stay centrally and cover the half space/central zone encouraging a pass out wide to the fullback, which is a pressing trigger, as stated previously. The difference between Liverpool’s press in the 4-3-3 and 4-2-3-1 is that the forth presser starts from a deeper position and is tasked with timing his pressing action. Any of the midfielders can decide to support the front 3’s press, but it’s usually the 3rd/most advanced central midfield player i.e. Milner/Lallana/Oxlade-Chamberlain.

The team’s press is triggered by an individual deciding to press a certain player or by baiting someone into playing a pass, or by reading where a player is going to play a pass. There are other pressing triggers, be it a loose ball or a pre-identified trigger (a player who struggles to play out of a press).

This is the shape that Liverpool employ and it’s more focused on blocking space as opposed to relentless pressing. If the press is bypassed while in the 4-2-3-1, the team are only left with two double pivot players and the defence in transition, whereas the emphasis on tracking back from the wide players in the 4-3-3 and the extra central midfield player allows for extra numbers to get back, as the team to retreat into a 4-5-1 shape. However, against inferior opposition, the 4-2-3-1 allows for superior counterpressing and defensive transitions.

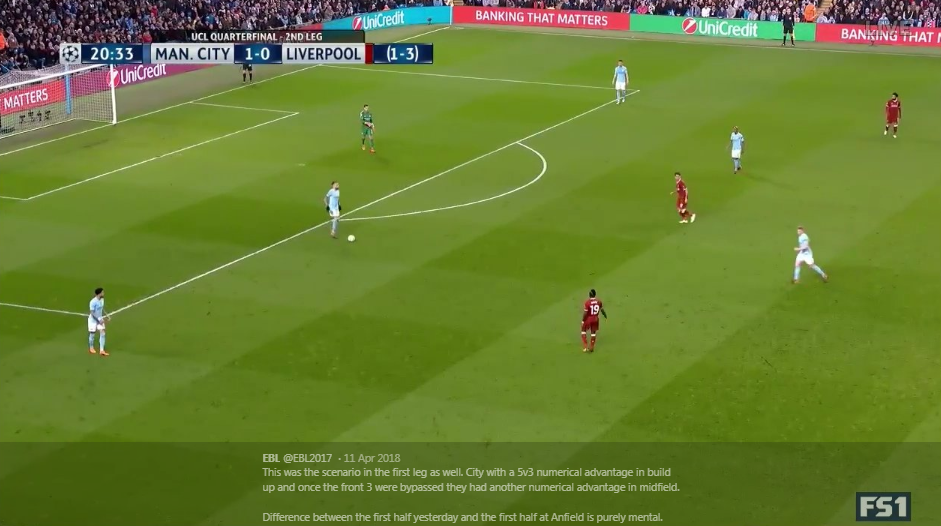

Although Liverpool’s settled shape is superior in the 4-3-3 compared to the 4-2-3-1, Salah’s tendency to stay high in transition results in Liverpool being overloaded on the left flank from time to time. This can be a weak point in Liverpool’s shape and causes a massive onus on the right central midfielder (typically Wijnaldum or Oxlade-Chamberlain), to provide extra defensive cover for Trent Alexander-Arnold at right back. That’s where the system can be overloaded with left backs and left wingers combining in the half spaces. Pep exposed this in the second leg of last year’s Champions League tie and Firmino was moved to the right wing with Salah up front in an attempt to combat it.

This is an example of where Liverpool can be overloaded on the right flank in the 4-3-3. Salah is nowhere to be seen here.

Liverpool’s system home vs. away

Liverpool’s press is always notably better at home because it’s largely based on adrenaline and the crowd unnerving the opposition, combined with the smaller pitch size. Roma/City/Bayern had a numerical advantage in the build-up phase yet they all conceded a high number of chances or goals because of how devastating the combination of the press, the offensive transitions, and the pressure of the crowd is.

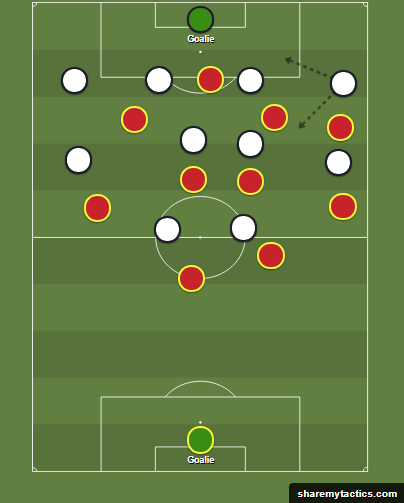

However, Liverpool’s press isn’t as efficient away from home if the opposition clutter the central area by playing a back three or a double pivot. This isn’t to say that Liverpool’s press can’t be nullified at home because it certainly can, but away, Liverpool’s press suffers from quick circulation and composure. Pep nullified the press with Stones-Laporte; Bernardo-Fernandinho in the game at Anfield at the start of the 18/19 season. The game finished 0-0, but City dominated the ball and quashed Liverpool’s press for the majority of the game because he stacked the central area with technical quality.

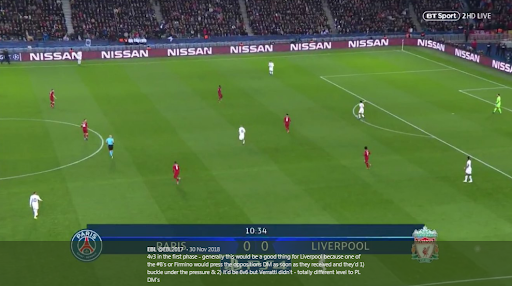

This is an example of an overload in the first phase vs Liverpool. This requires a high level of technical quality and composure from the 3 central defenders, but in particular the lone central midfield player. This game in particular was a masterclass from Marco Verratti, and he’s one of the few players in the world with the press resistance and technical quality to play out of Liverpool’s press virtually on his own.

This is another example of where Liverpool’s press is outnumbered as Pep created a 5v3 in the first phase. He also did this in the first leg of the same Champions League tie last season (17/18) but the lack of composure in deep areas from Fernandinho, Vincent Kompany, Kevin De Bruyne and Nicolás Otamendi resulted in them losing the game 3-0.

In the 0-0 earlier in the season Pep had one less player in the build up phase but had greater technical quality in John Stones, Aymeric Laporte, and Bernardo Silva. Fernandinho played better in that game but still made potentially costly errors early on.

Liverpool’s spacing/possession play in the 4-3-3

The build-up in the 4-3-3 is similar to the 4-2-3-1 in that it’s primarily personnel-related and there’s not many regular patterns of play. Klopp relies on the collective to play out from the back whilst instilling his own philosophies into the team.

The ball side central midfielder will contribute to build up on that side of the pitch if the team is being pressed, or if he wants to get involved deeper to make a creative influence. The defensive midfielder operates more centrally as opposed to in the half spaces and outside the lines as they do in the double pivot. He splits the centre backs and naturally makes more passes because it’s a one man role as opposed to a two man one.

Liverpool utilized the 4-3-3 for the majority of the 2017/18 season but regularly came unstuck against good quality low blocks. This was largely down to the spacing in the system but also because of the defensive transitional quality in that system vs. the 4-2-3-1.

The defensive transitions in the 4-3-3 are poor vs. low blocks because of the positional fluidity afforded to the central midfield players when trying to break down the low block. They were tasked with picking up spaces between the lines to enable vertical progression and create from there. The issue with this was they’d have to venture across the pitch looking for those zones and once play broke down, there was only 1 central defensive anchor in the central zone to break up attacks (Henderson).

In the 4-2-3-1, there’s two players to do that but that also maintains a player between the lines, so you get the best of both worlds in that system. Instead of midfielders venturing from deep to find spaces between the lines, Firmino will already naturally be placed there, and instead of players being caught in two minds between trying to find spaces between the lines and being in place for defensive transitions, there will already be a midfielder place in that zone.

Here, the attacking third is underloaded and it’s difficult for the players to combine in between the lines when they receive in that zone, because they lack players around them to do so.

This isn’t to say Liverpool’s spacing in the 4-3-3 is poor because with better personnel, the system did work. When Oxlade-Chamberlain got a run of games in central midfield in the second half of last season, the system worked very well. However, there were games when the system came unstuck and individual quality wasn’t enough to overcome the deficiencies within the system, i.e. Swansea away.

Why Klopp switched to the 4-2-3-1

This spacing issue combined with the defensive transitional issue is the primary reason why Klopp reverted to the 4-2-3-1 against inferior opposition throughout the season. The 4-2-3-1 allows a player to always be between the lines but also provides two central defensive options to nullify transitions. The 4-3-3 is unreliable in both of these regards.

Wijnaldum epitomizes the change in system. In the 4-3-3, he struggled when it came to making an impact between the lines and regularly sat in the middle of the park watching the game pass him by and was largely there for defensive transitional situations. However, once he was moved deeper into the double pivot, he had a better starting point to nullify those transitions.

By: @EBL2017

Photo: Gabriel Fraga / https://t.co/AdwHSL6jLS