Gonzalo Villar: AS Roma’s ‘Professor’ Oozing Class

In January 2020, AS Roma signed Gonzalo Villar from Elche CF, then in the Segunda División in Spain. The Murcia native arrived on a contract through June 2024, with the Giallorossi paying an initial fee of €4 million as well as €1 million in potential performance-based bonuses. Understandably, the deal was completed with minimum fuss and not much media coverage, outside of Italy and Spain, where the two parties involved were based.

Villar was only at the club for 2 months before the COVID-19 pandemic struck, and Serie A was put on hold. Even upon resumption, game time was hard to come by, as he made only two starts in all competitions and played a grand total of 312 minutes for his new club.

Fast-forward to today, however, and Villar has become an integral part of Roma’s tactical plans. With 24 starts and 11 substitute appearances across Serie A and the UEFA Europa League, he has shown himself to be a player worth relying on. But what makes him tick?

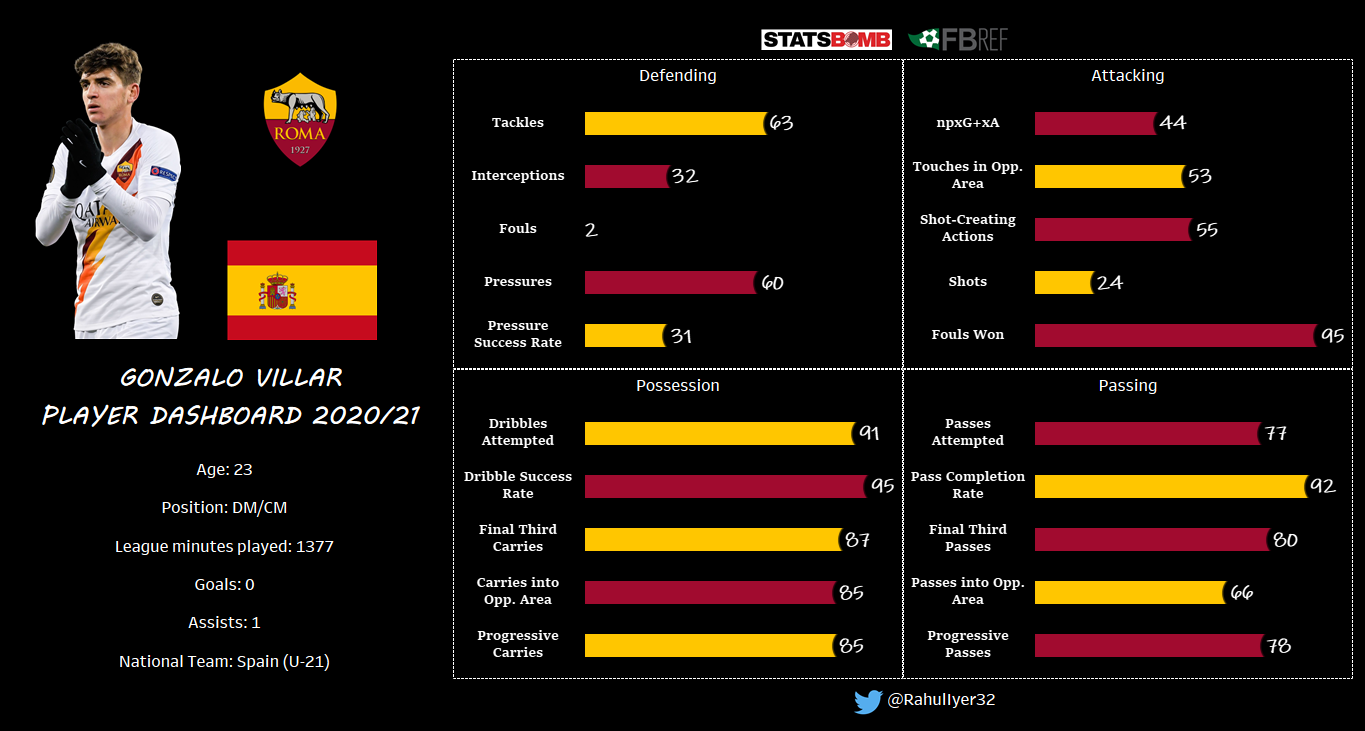

Statistical Overview

A look at some of Villar’s percentile rankings in relation to other midfielders across Europe’s top five leagues gives us an initial picture of the type of player he is. His attacking presence is fairly limited, and while he does a decent amount of defending, the quality isn’t all that great. Where his numbers really pop, though, is in the categories that have to do with movement of the ball through the park.

Villar’s ability to carry the ball forward and retain possession even under duress makes him an attractive option for manager Paulo Fonseca’s possession-oriented style of play. Whether driving forward from deeper positions, or making sure his teammates have time to reposition themselves, his skillset fits in quite nicely to the Giallorossi jigsaw.

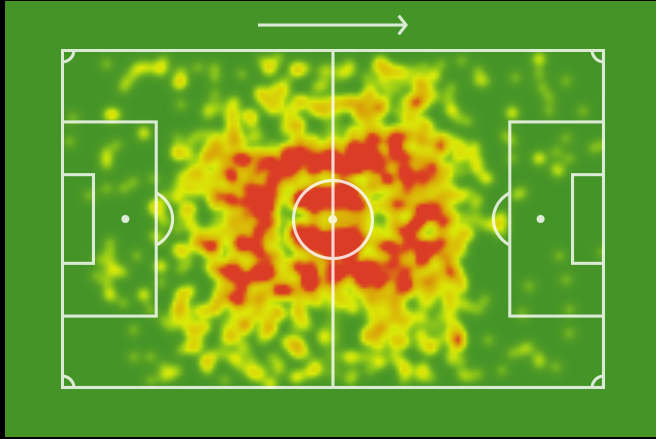

He may not be a superstar around the opposition’s box, or even his own, but you’d be hard pressed to find someone better between the two. His heatmap from the current Serie A campaign, shown below, backs this up quite nicely.

Photo: SofaScore

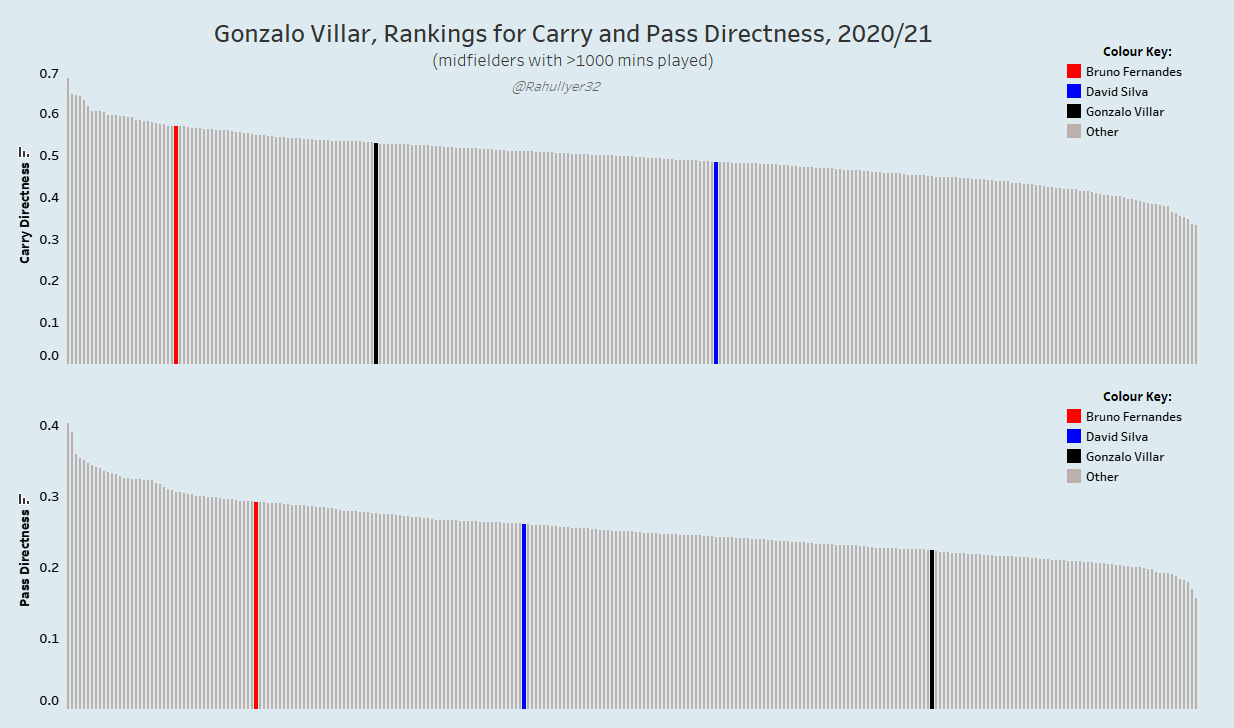

Another interesting observation from the data is shown in the following graphic. The metrics, pass and carry directness, measure how often a player moves forwards with the ball, as opposed to sideways or backwards. For context, observe Bruno Fernandes (red) and David Silva (blue). While there are slight variations in their style of play depending on whether they are passing or dribbling, one can conclude, fairly accurately, how ‘direct’ they are.

Of course, this will tend to be influenced by tactics to an extent, but we see that for Villar, the difference between how direct he is in possession versus when passing is far greater. When carrying the ball, he tends to move forward a lot more (approximately half the distance he covers is when moving forwards). That tendency is nearly halved when he chooses to pass the ball on to a teammate.

Tactical Fit

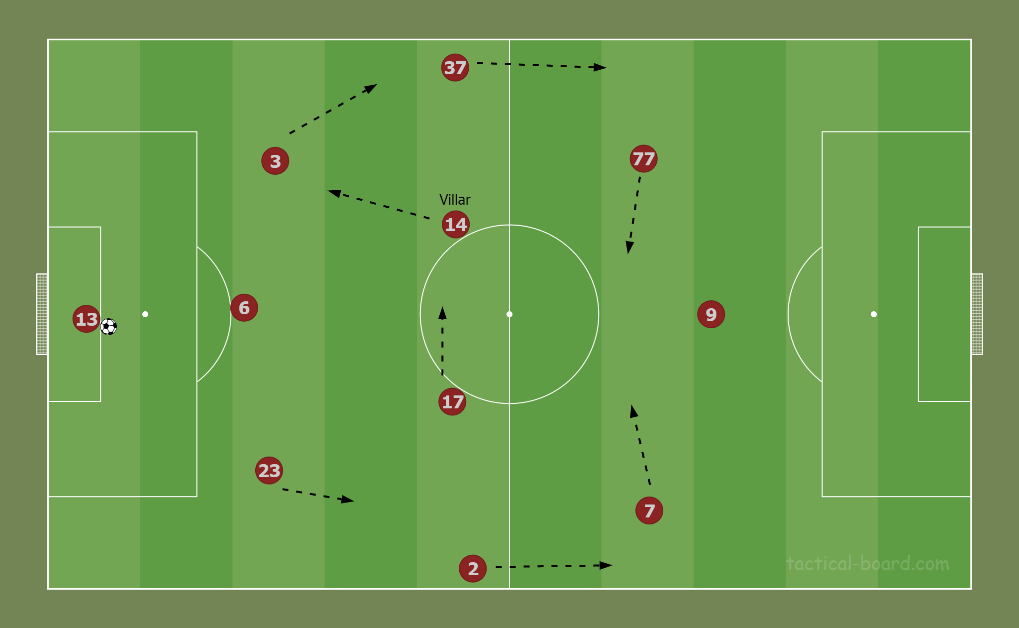

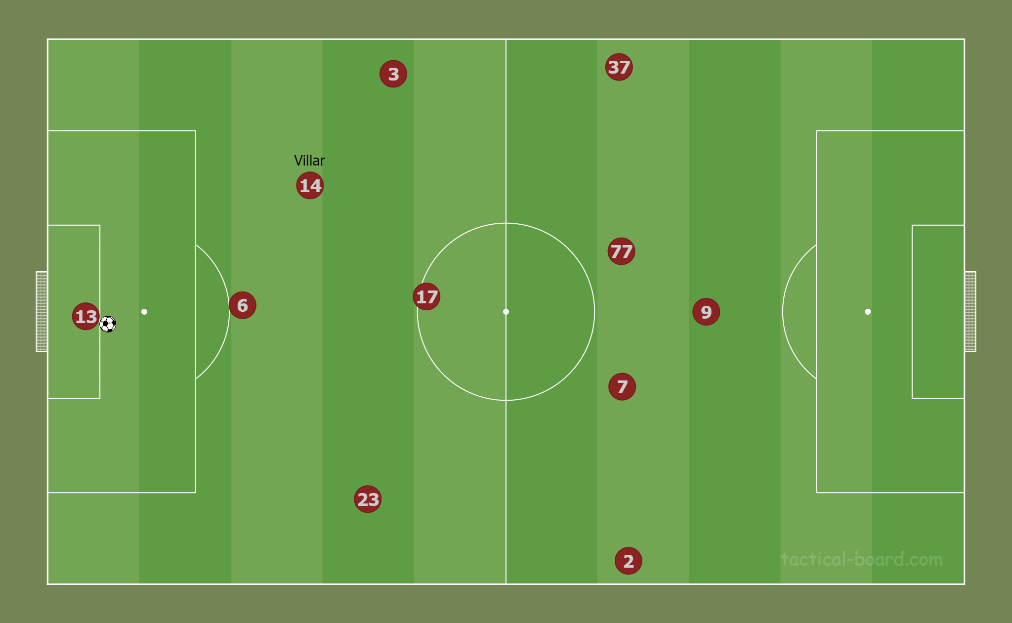

We can investigate this further, but first, we need to establish how he fits into this Roma setup. Fonseca’s preferred shape is a 3-4-3, most often with Pau López in goal, three centre-backs in the form of Roger Ibañez, Chris Smalling and Gianluca Mancini. Wing-backs Rick Karsdorp on the right, and Leonardo Spinazzola on the left, provide the width. The two central midfielders are usually Villar and Jordan Veretout, with Lorenzo Pellegrini and Henrikh Mkhitaryan flanking centre-forward Edin Džeko.

When building up from the back, Roma employ the rotations as shown below. The wingers tuck inside, to create space for the advancing wing-backs, thus facilitating an easy, if oft used, mode of ball progression. The lateral centre-backs also split, with the left-sided one moving wider. To cover the space and provide a passing option, the left central midfielder drops deeper with the right-sided one moving more centrally, to provide a slightly more direct option.

By involving the midfielders in the first phase of build-up, this allows Roma to get high-quality ball players in possession quickly, and gives them a better chance of beating the opposition’s first line of pressing. At times, Fonseca has even deployed Bryan Cristante, a midfielder by trade, as a starting centre-back, for more options against weaker opposition. Additionally, with the centre-backs moving wide, potential counter-attacking threats in the wider areas can be neutralised.

In most cases, Villar plays as the midfielder who fills in the left-sided space vacated by his centre-back. Of course, this is no hard and fast rule, and varies with game state and other personnel. Once on the ball, if the opposition chooses to sit off Roma, then Villar will look to advance with the ball into midfield by himself.

If pressed, however, which is the more frequently occurring scenario, he will look to move it into the wide areas, where progression is possible through the split centre-backs and wing-backs. Villar is one of Europe’s stand-out midfielders when we look at passes completed under pressure, averaging 8.82 per 90 minutes, better than 80% of his positional peers.

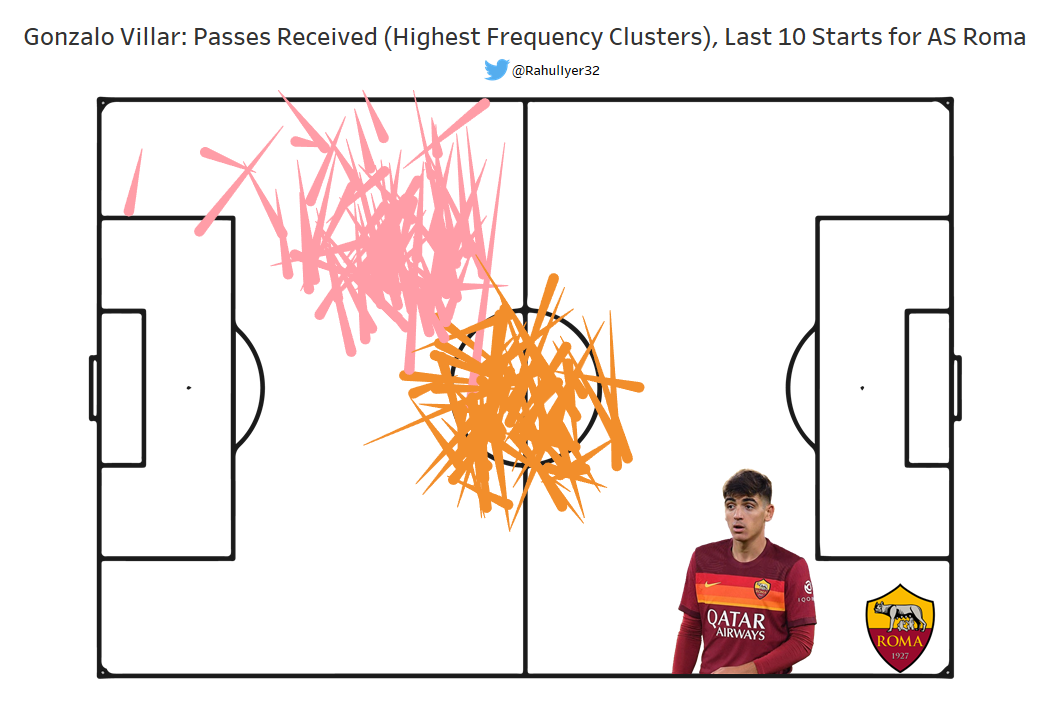

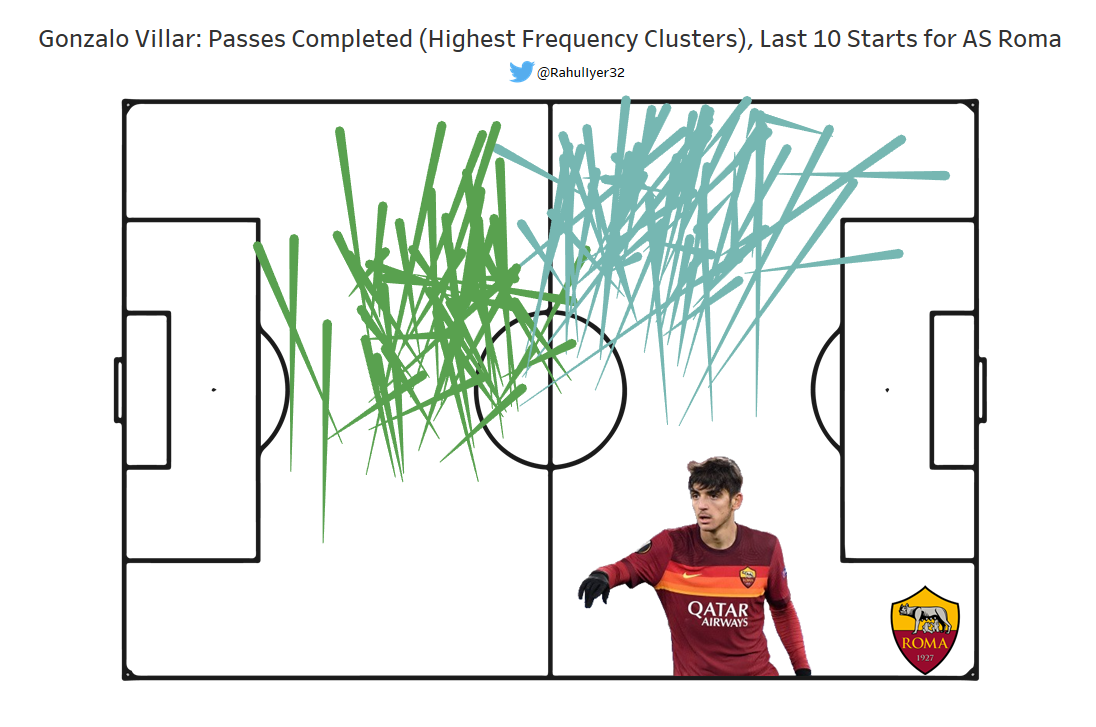

Looking at his most common pass reception locations, we can see this phenomenon bearing out quite neatly. Most of the passes he receives come from wide on the left flank, or from the middle of the pitch, mainly from his midfield partner.

The main types of passes that Villar himself plays are also easy to make out here. The two most common scenarios that we can make out here are when he receives and lays it off to his centre-back (green) and when he receives, turns, advances, and is then able to link up with his wing-back (blue). This also explains both phenomena discussed previously.

He is either driving into midfield from a deeper position, with not much pressure on him, so his carry directness is high. His pass directness is low because he tends to go sideways a lot more than forwards. It is also worth noting that the passes Villar receives are fairly short, while the ones he makes himself are slightly longer.

Explaining this comes straight from the man himself, who disclosed in an interview with Movistar, “I like to hold the ball. When I pass it, my hope is that I get it back quickly so that I can switch the play to the other side of the pitch.” He constantly looks to make himself available for one-twos and combination play, before spreading the ball and trying to stretch the opposition’s defence.

When playing for the Spanish U-21 side, however, Villar is given more license to move forward and get involved in the final third, with his regular midfield partner, Martín Zubimendi tasked with linking the defence and midfield.

Video Analysis

Now, while all this is good to talk about in theory, practical evidence is always an important part of evaluating a player. Not only can the use of video footage help us see the data being put into practice, but it can also help identify many facets of a player’s game that are simply not recorded.

In the above example from Roma’s 2-0 victory over Braga in the first leg of the UEFA Europa League Round of 32, we see how Villar drops deep, receiving from the wing-back, Spinazzola. Note how he scans the area behind him thrice before showing for the ball. Once he has the knowledge of what is behind him, he moves closer and receives the ball, opening up his body and orienting himself towards where he wants to move.

This is important, as other players who receive with a closed body shape will require an extra second to look up and then take action, which could lead to them being dispossessed. Essentially, it is a linear process. Because he has scanned, he knows how to orient himself. As a result of this, he can get into a good receiving position, and due to the fact that he possesses a trustworthy first touch, he can receive even while he is in the process of looking up.

Now, with no pressure on him, Villar quickly makes for the open space in front of him. This proactiveness now creates a problem for the opposition, about whether to press him or allow him to got further. In this case, Villar is set upon by three Braga players, which he evades elegantly before laying the ball off. The upshot of this move is that now, having attracted three opponents to himself, his teammates will have more space, and thus more time, to build the play.

Here is another clip, from the same game. Again, Villar’s scanning, body orientation and drive through midfield are close to perfect, and he finishes this passage of lay-off with a superb pass, fizzed into the feet of Henrikh Mkhitaryan, after drawing two defenders onto him, and influencing the position of one more, who has moved to cut out a potential lateral pass.

Villar is also capable of providing a creative spark from deeper positions, with long balls to Džeko, or for the inside forwards to run onto. It helps that he finds a teammate with over 80% of his attempted long passes, so it is a role he could potentially play, if the team needed him to. Here are a few examples of his delivery from deep:

His close control and calmness under pressure also make Villar a useful asset when defending, as we can see in the following couple of examples. Immediately after winning the ball back, Villar is able to retain it, draw opposition players into a counter-press and then move it into space to get an attack going.

Staying on the topic of defending, the actual act of winning the ball, or defending one-on-one situations isn’t one of Villar’s strongest suits. He can often look leggy or tired as games wear on, which is something to keep an eye on. In addition, perhaps to make up for his slight frame, he does tend to overcommit and give away silly fouls, such as this one:

Conclusion

Whether his long-term future lies in Rome or not, he is certainly one for the future, at both club and international level. Currently representing Spain at the U-21 European Championships, there will most certainly be watchful eyes on him, and they should be impressed with what they see, especially if the team goes deep in the competition. Villar has already caught the eye, with this stunning finish against Slovenia in the tournament opener, and leaving this piece after watching it really isn’t the worst thing to do.

Villar is by no means the finished article. Still just 23 years old, he has time to mature and iron out the flaws in his games, but for a youngster who counts Andrés Iniesta and Sergio Busquets among his idols, his technical ability combined with his cerebral nature, ensures that he is very much on the right path to emulating them. (Fun fact: alongside his footballing career, Villar is currently studying Business Management and Adminstration at the Universidad Católica San Antonio de Murcia, in his hometown, earning him the nickname ‘The Professor’).

The likes of Fabián Ruíz, Dani Ceballos, Thiago Alcântara and Juan Mata have won the Golden Ball in recent U-21 Euros, with all but Ceballos leading his side to the gold medal. Villar could be the next Spanish midfield maestro to dazzle for his country in this summer’s tournament and spearhead La Rojita to glory.

By: Rahul Iyer

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / DeFodi Images