Dissecting the Ins and Outs of Build-up Play

I was watching the FA Cup Final between Arsenal and Chelsea a few months ago and a special moment in the game caught my eye. It was the moment where Arsenal’s Nicolas Pépé was near his own penalty box trying to bring the ball out from the back. It seemed risky when Pépé played a pass to David Luiz, but the rewards were worth it when Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang found the Ivorian winger a few seconds later with a lot of space ahead of him through a third man pass.

Upon receiving the ball, Pépé played through the Chelsea defence, breaking multiple lines of press and playing the ball into the path of Ainsley Maitland-Niles, but the move didn’t account too much in the end with the ball going out for a goal kick.

Nevertheless, I was enthralled by that move and was pleasantly surprised to see the improvements Arsenal had made in a few months in the execution of their build up. It was then that I decided to dig deep into build-up play and excavate the small details that would help in performing a successful build up from the goalkeeper.

Arsenal progress up the pitch through build-up which helps them create a free man in the final third. This is something that has been worked on in the training ground by Arteta and his staff in the last few months; until mid-February, Arsenal had the lowest progressive distance in the Premier League from both short and long goal kicks.

In the last few months, Arsenal’s build-up play and subsequent progression up the pitch has been eye-catching with positive end results (often progressions into the opponent’s half and sometimes into the opponent’s penalty box). In this article, we’ll be analyzing the metamorphosis of the build-up play.

Origins of the Build-Up

It’s difficult to find the exact origin of when teams started focusing on improving their build-up play, but it can be assumed that early proponents of the possession game like Arthur Rowe, Stan Cullis and Vic Buckingham encouraged their team to play out from the back. There are other major influences such as legendary Arsenal manager Herbert Chapman and the famous Hungary team of the 1950s who rewrote the history books with their possession-based attacking style of play.

The latter didn’t show signs of repetitive build-up play from the goalkeeper, but there was a recognisable intention to possess the ball and break lines to progress through the pitch. I found an interesting bit from Martí Perarnau’s 2016 book “Pep Guardiola: The Evolution,” which spoke in detail about Guardiola’s time at Bayern Munich and included this passage about the build up from the early 1900s.

“In 1901, [former Sheffield United captain Ernest] Needham wrote these words for an Association Football publication: ‘Sometimes, and I’d like to emphasise this point, linking up play between defenders and midfielders is a good decision. If a defender can feed the ball to his midfielder so he can then push the play up the pitch he should do that without hesitating for a second instead of simply launching the ball long and far with a big hefty boot’.”

“This approach is much more successful than the way teams habitually play. Too many defenders, whenever they have the chance, just lump the ball as hard as they can and reckon they’re pretty heroic.

They’re totally forgetting that nine times out of ten the ball flies over the head of their striker, landing at the feet of the rival back four who then counter-attack because you’ve gifted them possession.”

Guardiola would have likely agreed with Needham and Jimmy Hogan, another like-minded English coach of whom Norman Fox wrote in his 2003 book “Prophet Or Traitor? The Jimmy Hogan Story”:

“Hogan maintained that the best and safest way of playing was to bring the ball out carefully from the penalty area and move forward using short passes.

Although he had nothing against long passes per se, he said that precision was essential. In fact he insisted on precision. Thumping the ball long only to end up giving it to the opponent was never part of his tactical plan.”

There have been other advocates of build-up play in Ricardo La Volpe and Juanma Lillo, both of whom have inspired Guardiola. The Catalan manager wrote in El País in 2006, “La Volpe obligates his teams to play out from the back, which means players and the ball advance together at the same time. If only one [player] does it, there is no reward, no value. They have to do it together, like couples do when they go out together.”

Whilst Guardiola has been a massive proponent of build-up play, he also recognizes the risk attached.“A lost possession from where they play the ball out from could be terrible. But not only do they know it, everyone knows it. That’s why everyone evades doing the same as the Mexicans. Some start play, others play out.”

Born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, La Volpe spent the bulk of his 36-year managerial career in Mexico, where he would introduce the famous build-up play method ‘La Salida Lavolpiana,’ or the ‘Lavolpian Exit.’

‘Because playing out from the back isn’t the goalkeeper giving it to the center-back and the center-back passing it just for the sake of it,” said La Volpe in an ESPN interview in 2018.” The job is to get the ball into midfield with numeric superiority, with a man spare. And if you don’t have a man spare in the middle of the field after playing out, it’s because the opponent left you man-on-man further forward.”

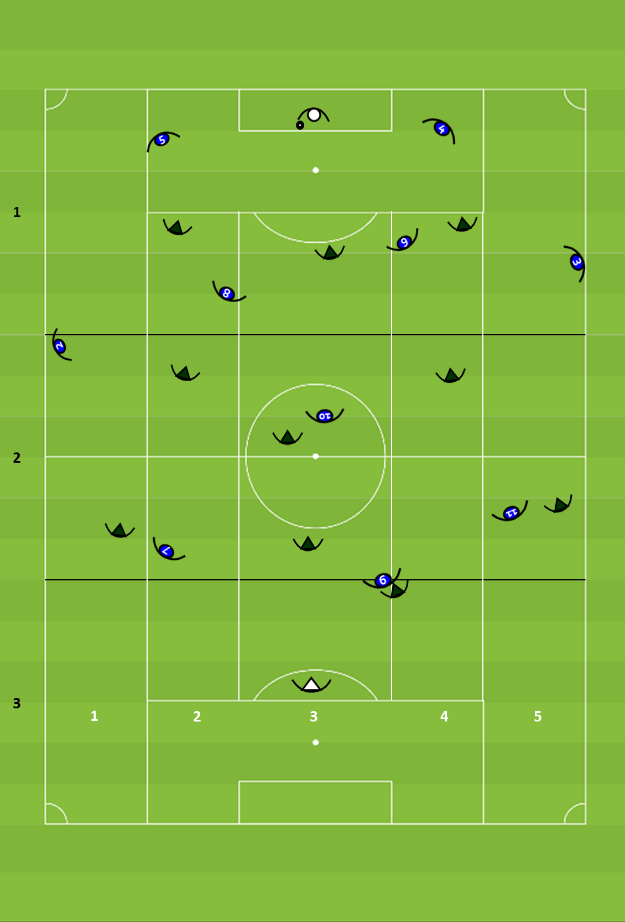

In order to execute the Salida Lavolpiana, the two centre backs spread out to the edge of the box where the two strikers follow them, leaving space for the defensive midfielder (6) to step in relatively unopposed and progress the ball up the field. The concept revolves around numerical superiority and creating space for your team mate by dragging your rival in a direction away from the ball recipient.

Before retiring in 2006, Guardiola spent the final season of his playing career under Lillo at Dorados de Sinaloa, where he absorbed plenty of tactical ideas and fundamentals, later calling Lillo his “biggest influence.” Today, Lillo works as Guardiola’s assistant coach at Manchester City.

‘If players don’t take the time to construct play, it will be difficult to get the ball to the right places up the pitch and then dominate the opposition,” stated Lillo in “Pep Guardiola: The Evolution.” “If you play the ball up field at top speed all the time, hitting first–time long balls, the ball will be back on top of you in seconds.”

“Up and down, up and down… You have to pass when the moment’s right, to the right player. Get that wrong and you’ll be playing long balls for your opponents to gobble up and then come at you in numbers.”

There is a common trend of risk vs reward in the statements of these famous coaches. What we can already gather is that while it is risky, the reward can be fruitful because reaching a certain area on the pitch with more numbers than the opponent is more likely to generate scoring opportunities.

To reach the midfield zone with numerical superiority requires a great relationship and a deep, synchronised level of understanding of the game (functionality) between the players. Perhaps this is why coaches such as Guardiola and Gian Piero Gasperini of Atalanta spend hours on the training ground trying to perfect the execution to improve the functionality and automatism of the players.

If I have to sum up what the coaches above say about build-up, two key points come to mind: to move together in a collective but at the right moment. We can see a prime example of this in Arsenal’s build-up against Manchester City. 10 seconds after maneuvering out of the press, Arsenal enter City’s half with a numerical advantage.

Arsenal can effectively advance into City’s half with a numerical superiority after maneuvering their press in the build-up phase.

Build-up Play: What is it?

Build-up play can be defined as reaching the opponent’s half, preferably in an advantageous situation (a superiority so to say). To build up, you can use short passes, long passes or a dribble and these are all valid as long as you reach the opponents half in a superior position. The UEFA Champions League semi–final between Paris Saint-Germain and Red Bull Leipzig featured an illuminating moment when PSG scored their second goal from a build–up error by Leipzig goalkeeper Péter Gulácsi.

The commentator stated, ‘There is a difference between playing out from the back and playing from the back. The former means you play out and reach the forwards. The latter means you play from the back and risk losing possession.”

This is an interesting categorisation between the two terms: the first implies that you are building up from the back with an idea to reach the forwards, while the second implies you are playing for the sake of playing without an idea or awareness of your execution.

For the purpose of our research in this article, we have only accounted for build–up actions when the goalkeeper is involved (mostly by passing) in the build up. This doesn’t necessarily mean that a build up is not possible without the goalkeeper’s involvement, since there are plenty of actions when the ball has been recovered by or passed to an outfield player in the defensive third, who is then able to build up and reach the opponents half without using the goalkeeper.

This is typical when the opponents prefer to setup in a mid or low block. Having said that, there are a lot of advantages to the goalkeeper’s involvement in build–up play. The biggest being using the extra attacker and stretching the field of play and, as a result, increasing the distance between the first and last defender. With the goalkeeper’s involvement, you can start setting your structure which will help you progress up the pitch.

There is a notable tweet I stumbled upon regarding the difference between a long ball and a long pass up the pitch. There is a big misconception in football that a long pass is against the fundamental idea of build up. We disagree.

If you look at the definition above, a long pass is a great way of reaching the opponent’s half in an advantageous situation. Manchester City goalkeeper Ederson is a master of using the long pass to exploit spaces in the opponent’s defensive structure. But that comes through a combination of training, the players’ understanding of your idea and their ability to execute that idea on the pitch.

Photo: Getty Images

Having said that, if a team uses the long ball for major periods of the game without a clear idea of achieving superiority and relying on the second ball/a flick on, that would not be considered a ‘build-up’ since the chances of reaching the opponent’s half in an advantageous situation is something you can’t control.

“It’s easy to play long ball. For example, you play long ball, you recover the second ball, it’s okay. But when the ball is in the air, you don’t know what will happen with the ball,” stated Domènec Torrent, who served as Guardiola’s assistant from 2007 to 2019, in an interview with Spanish football expert Graham Hunter.

“Sometimes people say it’s dangerous to make a build up. I don’t agree. Because if you make a build up you know exactly [what] you want to do. You are in control. If you can count the cards, you might still lose but you give yourself a big opportunity. It’s the same thing: you give yourself a higher chance by having more percentage, more control of the ball.”

Since superiorities are important to the idea of build–up play, we will briefly talk about the five superiorities that exist with teams that practice positional play.

- Numerical superiority – This refers to having more numbers than the opposition in a certain space on the pitch.

- Positional Superiority – When player(s) are positioned in a superior (vacant) space on the pitch

- Qualitative Superiority – An individual or group having superior quality (technical/physical/mental) than the opponent(s). This can be as simple as a player having more technical quality than the opponent (Lionel Messi vs a group of opponents) or a superior physical quality (Bayern Munich players in the Champions League quarter-final vs Barcelona).

- Dynamic Superiority – Having a spatial and awareness superiority over the opponent where you can exploit space better than the opponent. A simple way to explain this superiority would be to label it ‘dynamic space occupation’ or ‘momentum superiority’ since it is better to arrive on to the ball than receive it static from your position. This superiority makes it easier to attack and harder to defend.

- Socio-Affective Superiority – Connections and relationships between players and teams. The stronger this superiority, the easier to play with each other. This is an important superiority because one addition to the game can often change the flow and dynamics between the group. A good example is Kingsley Coman, who started the Champions League Final against PSG because his coach Hansi Flick felt Coman would have a point to prove against his boyhood club.

Why Do Teams Build Up?

There is no short way to answer this question but there lies a lot of sense behind what Guardiola, Lillo, La Volpe and Torrent say about their affinity towards the build up. Most coaches now prefer the build up to dominate the game using the ball.

Lillo had this to say about his belief, “If you develop your play slowly, you’ll be under pressure from the start, for sure. But if your football’s very fast and direct, you’re going to have the ball thrown back at you almost immediately. In football, to get up high, you need passing movements in the main part of the pitch.”

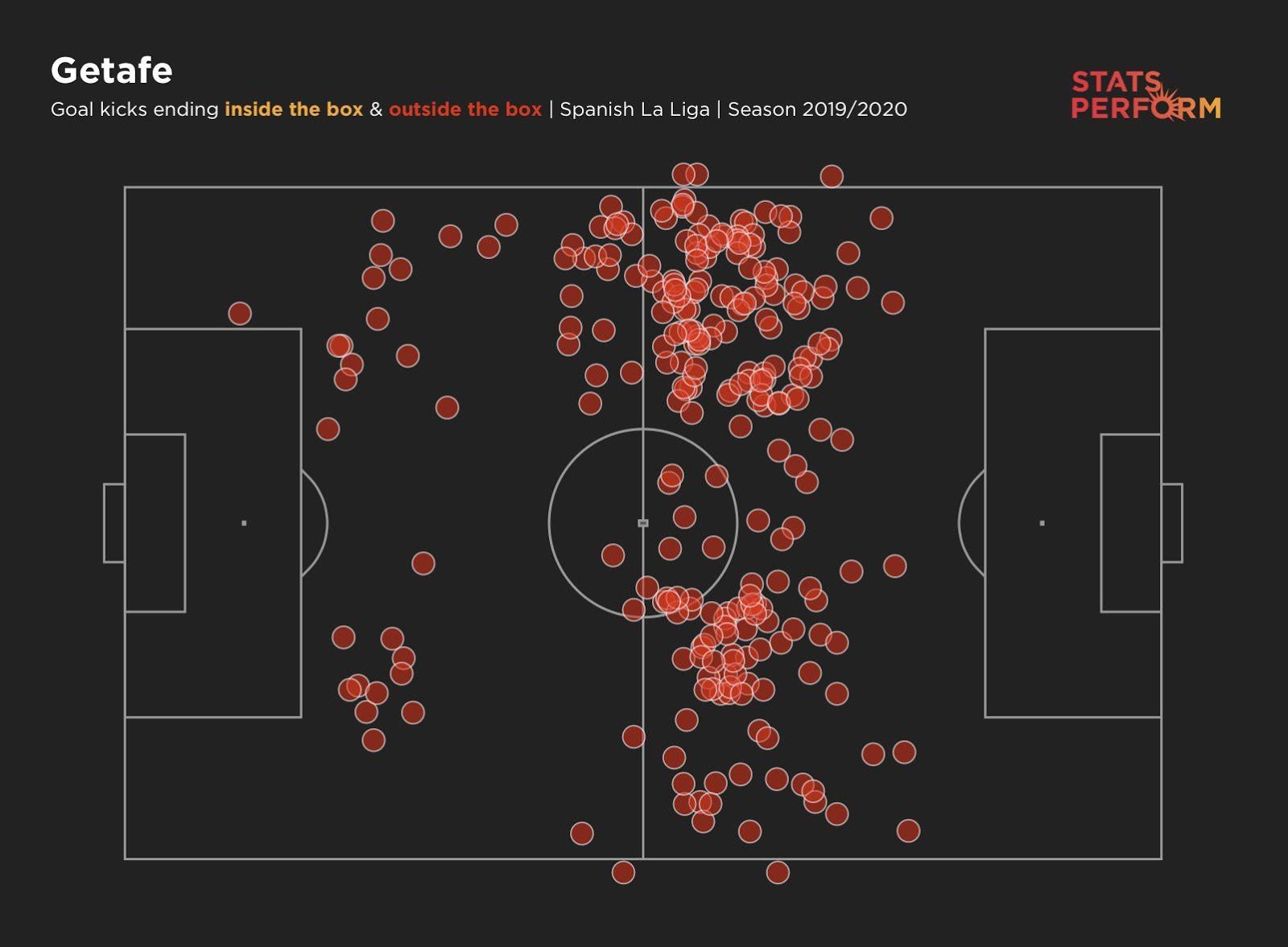

Photo: StatsPerform

The above image shows Getafe as the only team in the top 5 leagues in Europe to not play a single goal kick inside their own penalty box. As more and more teams look to progress out of their own half with short, calculated passing, José Bordalás’s Getafe are certainly the last of a dying breed.

It’s fascinating how football has evolved over the years. In the past, we saw a lot of teams trying to dominate the opponents without the ball but we are now seeing a change where teams recognise the value of the ball. More teams than ever now want to be the protagonists of the game, trying to dominate the opponent using the ball.

In Serie A, there has been a 20% rise in short goal kicks and there has been an increase in other leagues too since the new goal kick rule has come into effect. Under Chris Hughton, 7% of Brighton & Hove Albion’s goal kicks were short. This year, with Graham Potter at the helm, the number of short goal kicks has gone up to 77%, per The Athletic’s Tom Worville.

The current Europa League holders Sevilla are a good example of suffocating the opponent using the ball to reach the opponent’s half and dominate even further. The Italian teams (Roma and Inter Milan) learnt that the hard way. But if we had to look deeper into why teams prefer to build up, we will find many layers to that answer.

- Control – The biggest reason is so teams can control the game with the ball. In an article in the Telegraph, JJ Bull wrote, “At the elite level, managers should seek to control as many aspects of a match as they possibly can and although throwing a dice will occasionally make it come up six, there are too many uncertainties and possession cannot be guaranteed. By building up from the back a team can be coached to construct attacking play under conditions the manager has chosen.”

Another excerpt from Guardiola’s time at Bayern should give us a better explanation behind his philosophy of playing out from the back. “I said to them, ‘Okay, you like long balls? No problem. But you should understand one thing: the faster the ball goes, the faster it comes back.’ It’s just one of those bloody things you have to accept in football. In eight out of 10 situations when you kick the ball long, the opposition central defender is going to get to it and win it back.”

“You’re running after it and it’s already on its way back. They’d say: “Who cares! Get it up the pitch right away, hit the ball long. It was a fucking pain in the neck to get it over to them and I had to explain it over and over again, as no doubt I’ll have to in England as well.”

By controlling the game through possession of the ball, you can also manage the tempo of the game along with the rivals’ intentions. This is why Guardiola prefers the 15–pass rule before attacking the opponent’s goal and without the build up this is impossible.

Photo: Paul White / Associated Press

2. Staying Connected – The next reason for the build up is so you are connected as Guardiola said earlier ‘like couples’. If you bring the ball out cleanly by staying connected through the pitch with the right distances, you can keep possession effectively and make your transition to attack easier.

Guardiola explained how he won the ball back so quickly during his time at Barcelona. ‘This happened because we’d move forward together as a team. There wasn’t much space in between the players or the lines and when they lost the ball it was usually easy to get it back.’

3. Progress – The connectedness in the build up also allows you to progress up the pitch together moving from one zone of the pitch (your penalty box) to the opponent’s half without breaking your structure. Worville, who measured some data over the past two seasons found on average teams that take a short goal kick progress up the pitch 49 metres as opposed to teams that take a long goal kick and progress up the pitch 39 metres.

This comes as no surprise really because if you read what some positional play experts have said above, you will realise that the best way to progress with control and superiority further up the pitch is by playing out from the back.

4. Superiority – Another reason why the build up is of value is to create superiority behind the line of pressure. If you build up, it is likely that at some point the opponents are going to press you. By attracting rivals, you can create superiority behind them allowing you to progress up the pitch with a numerical superiority.

In the build-up play, the team always moves up the pitch as a unit. As a result, you stand to have greater numbers in front of the opponent’s goal compared to the long ball where you give the opponents the possibility to recover the lost numbers.

5. Unpredictability – The build up also allows your team to mix things up and, as a result, makes your team unpredictable and difficult to press. Football tactics writer Michael Cox said in The Athletic’s Zonal Marking podcast that the major impact of the new goal kick rule has been a change in the way teams press.

“It’s actually quite difficult now to press on goal kicks and the greatest example of this is Manchester City. On one hand Guardiola’s teams want to play out from the back but on the other hand because you can’t be offside from a goal kick, City have exploited that a lot with Ederson just hoofing the ball over the entire side, often to [Raheem] Sterling or [Sergio] Agüero or [Leroy] Sané running through.”

“So, because teams are so focused on being compact, it’s very difficult to be compact if you can’t play an offside trap like you usually would and you’ve now got to cover 18 more yards up the pitch. So, we’ve seen teams just spread across the pitch in a way that we really [wouldn’t have] seen before.”

Photo: Alejandro Rios / DeFodi Images – Getty Images

Having a goalkeeper with the kicking range and accuracy of Ederson helps to give you the option of going direct towards the strikers or exploiting spaces between the lines for the strikers, midfielders and full–backs to receive the ball.

If you are defending against Manchester City’s goal kicks, you can’t afford to give them an inch of space because they will exploit it. If you press them high, they will use the space behind you and if you drop in a low block, they will play the short pass to the centre-back and build play from there.

Former Arsenal player and current pundit Stewart Robson explained it perfectly in his piece for ESPN: “Starting moves from deep also allows teams to make the pitch bigger.”

“Coaches have long used that term in relation to width, but with players dropping so far to receive the ball from their goalkeeper, as well as strikers threatening space behind opposing defenders, making the pitch ‘big’ is equally applicable to length.

“This makes it more difficult for defending sides to remain compact. The build up is the start of your attack and the more weapons you can have in your arsenal, the easier it is to achieve your objectives.”

6. Enjoyment – Lastly, the players enjoy it when they are in possession of the ball. Azzurri legend and current Juventus manager Andrea Pirlo wrote this in his dissertation, “There are big benefits to bold, attacking football. There’s more of a feel-good factor. Players and staff buy-in more. You need all that to forge the empathy behind all successful teams.’”

When questioned about it, Guardiola, a pioneer of this attacking football philosophy, stated in an interview with SFR Sport, “Football players became football players because they enjoy [playing] with the ball and I try to let them enjoy remembering when they were young players.”

Principles

As a fan trying to understand build-up play or a coach wanting to implement this into their team’s style of play, it is important to understand the basic principles that are fundamentally required for any team to progress with the ball through the thirds.

It is under the ambit of these principles that coaches can implement their own ideas and innovations to achieve their goal of successfully progressing play from the defensive to the attacking third.

Width and Depth (Occupation of Space)

To start, we breakdown the pitch into five zones vertically (two wide, two half spaces, and the central) and three thirds horizontally (defensive, midfield and attacking). When a team is looking to build-up play, it is important that they occupy all the spaces either positionally or by arrival (dynamic).

Advantage: By positioning players in all five zones (to provide width) and three thirds (depth), the team ensures that they have multiple passing options available at different angles (triangulations).

In turn, this commits more defenders from the opposition to the press, as they have more passing options to block. In a situation where a team does not follow this principle, it becomes easy for the defending team to make the play predictable and press the attackers to win the ball.

Sub-principles

- Connecting attackers: Teammates position themselves in a way that the on-ball player can find them with his pass. Distance between the players varies according to the game idea. Lesser distance leads to quick passes and combinations, while more distance can allow the player more time on the ball.

- Triangulation: The off-ball attackers need to create open passing lines (minimum two options) for the on-ball player to reduce the predictability of the attack. The more passing options available for the player the more difficult it is for the defenders to press.

- Spatial Awareness: Players need to be aware of where the space is available on the pitch. Depending on the game idea, this space can be occupied positionally or by arrival.

-

Positioning

As a continuation of the previous point, the players need to position themselves in a way that they can gather information on the pitch (space, opponents, teammates, etc) to progress the ball forward. According to the game idea, the positioning of the players changes in order to achieve the desired objective.

Advantage: With the aim of the build up being to progress the ball to the opposition half with an advantage, the attacking team positions its players in a way that they can create the necessary superiority to break the opponent’s defensive lines. This includes dynamic occupation of favourable spaces on the pitch and making proactive and reactive movements according to the opponent’s press.

Sub-principles

-

-

- Positioning on Different Lines: The supporting players should position themselves diagonally to the on-ball player, on different lines (both vertically and horizontally) and provide an option for the team (either with the first pass or the second).

- Gather Maximum Information: The receiving player should have an open body shape and be aware of his teammates and opponents around him before receiving. Based on this information, he may receive the ball with the back foot (space to move into) or front foot (defender close to the player).

- Diagonal Support: By positioning yourself in relation to the defender (on the same line as his shoulder) the player creates an opportunity to break that line of press with his first touch. The body shape of the receiver and first touch are essential for this to be completed successfully.

- Interval positioning: The attacker can also position himself between two lines of defence (midfield and forward or defensive and midfield) or in the space between two opponents. This ensures that the player occupies multiple opponents at the same time, which may lead to the defenders compressing in that area of the pitch (leaving more space for the attacking team elsewhere) or a through ball being played to this player between the lines.

- Cover Shadow: This is the space that is left behind the pressing defender. Supporting players need to ensure that they move out of the cover shadow of the pressing player to provide an option to the on-ball player.

- Counter Pressing: While progressing play forward, the team needs to accept that at times the build up will not be successfully completed. For this reason, they need to position players behind the ball to counter press in a situation of ball loss.

-

Rotation

To destabilise the opposition shape and create space for yourself or your teammates, the attackers can rotate positions with teammates on the same line (midfielders switching with each other) or on different lines (midfielder switching position with a centre–back or full–back). The objective of this principle is to disorganise the opponent and create space to progress the attack.

Advantage: Players rotating their positions forces the defenders to make a decision between following the attacker, which could create space for another player, or to cover the space, in which case the attacking team has a free man during the build-up. Vacating your position (moving out of your area) can drag the defender out from that position as well, freeing up space for the on-ball player to play grounded second line passes.

Sub-principles

-

-

- Dynamic Movements: Players occupy space dynamically and change position according to ball, teammates, space and opponents.

- Opposite Movements: Players use triggers from their teammates to make a run opposite to their teammate. The objective is to drag your defender with you while creating space for your teammate to exploit.

- Check-in, check-out: Supporting players make movements with an objective to destabilize the defender and drag him away from favourable spaces which they or their teammates can use to progress play.

- Third–man run: One of the most effective ways to use a spatial advantage, a third–man run focuses on attracting defenders towards the ball before playing a pass into space for a teammate.

-

Superiorities

As discussed earlier in the article, teams can create superiorities in the form of numerical, positional, qualitative, dynamic and socio affective. Creating a form or a combination of different superiorities is the basis on which teams progresses their attack. Teams can also use inferiorities to create superiorities, for example, creating an underloaded situation (numerical) to progress with a dynamic superiority.

The team building up has to recognise on the pitch, or pre-determine, what kind of superiorities they wish to create and make particular actions to execute the same.

Advantage: Creating superiorities ensures that the team builds play with an advantage and the chances of losing the ball is reduced. Creating superiorities can also force the opposition to commit more defenders into that part of the pitch, thereby leaving space in other parts.

Sub-principles

-

-

- Combination Play: This can be done in the form of a ‘one-two’ pass, a ‘wall pass’ or a ‘lay off’. Players pass the ball and move dynamically to occupy new spaces on the pitch.

- Third–man pass: Players connecting to pass the ball to a teammate in an advantageous position. Usually used to shift the opponents and pass the ball to a player with more time, space or a better position.

- Driven Pass: While playing a long pass, there is an advantage if it is played with pace (driven) when possible over a lobbed pass. Otherwise, the defending team may be able to shift and close down the space. In a situation where the player would need time to reach the target space, the team can prioritise a lobbed pass.

- Switch Play: The objective of this sub principle is to shift the opposition on to one side of the pitch to create space on the other side. Teams can create spatial, numerical and/or qualitative superiorities by switching the attack.

- Recognising bonds between teammates: As players spend a lot of time on and off the pitch together, some develop a higher understanding of each other’s movements. This can be utilised by the team while building up their attack (for example, Messi and Alves/Alba).

- Continuation of run: After passing, the players should continue their run to be further involved in the attacking play. This can help the team in creating overloads and imbalance the opposition shape. This sub-principle, although important, is dependent on the position of the player (on the pitch), role in the team and position of teammates and opponents around. At times the player may need to hold his position to protect space behind.

- Quality of Pass: This includes the weight of the pass, played to the correct foot of the teammate (according to the press).

-

Creating Space

An attacker in space has the time to pick multiple options (switch play, dribble, through ball, etc) with the ball at his feet. It makes the next move of the team unpredictable for the opponents. That is why the principle of creating space is pivotal to a team’s build–up play. The attacking team can organise their build–up play to either create space between the opposition lines or behind their defensive line.

Advantage: Creating space between the opposition lines gives the on-ball player more time to pick out his next option. The team can use this opportunity to change the direction of the attack (isolate the far–side opponent by switching play), play a through ball/long ball to a player making a run behind the opponent’s defensive line, etc.

Sub-principles

-

-

-

- Dismarking: The supporting player needs to time his movements in a way that he can move away from the defender to create space (for himself or his teammates) when there is an opportunity to receive a pass. This is usually achieved with a check-in, check-out movement by the supporting player.

- Dynamic Occupation of Space: Players position themselves on the pitch in a way that results in certain spaces being left free to be occupied ‘dynamically’ when the pass is played into that space. Players receive the pass by arriving into that space instead of starting from there.

- Combination play, third–man pass and third–man run are some of the other sub-principles used by teams to create space between or behind the defensive line of the opponents.

-

-

Fixing

Fixing, as the term suggests, means to ensure that the opponent(s) is stuck in that position and do not shift to cover any other space or attacker.

To facilitate the build-up, the attacking team can either fix the opponent to one side of the pitch to switch the ball and take advantage of the spatial and/or numerical superiority of the other side, or use it at a more micro level where an attacker fixes an individual opponent by dribbling towards him and creating a superiority (numerical, qualitative, etc) around him to progress.

Advantage: The objective behind fixing opponents is to create and/or maintain superiorities for the team. The action ensures that the opponents are stuck to their position or their side of the pitch and the attackers can progress forward with an advantage.

Sub-principles

- Control the Pace: Player to fix an opponent by slowing down or pausing the attack. This can lead to a defender pressing the player, leaving space behind for the attacking team to exploit. This action also buys time for the teammates to occupy favourable spaces on the pitch.

- Bounce Pass: A team uses bounce passes to attract opponents towards them (bait) by playing multiple passes between teammates on the same line. When the defenders try to press, it creates space behind them for the attackers to exploit.

- Flatten the Press: The objective of this sub-principle is to create space between the lines for the attacking team. The team can use bounce passes or a dribble to attract multiple defenders towards them, which creates the space between the lines for their teammates to exploit.

- Fixing ‘Off the Ball’: Supporting attackers can fix defenders by making runs which are visible to them. The objective of this action can be to drag them away from a particular space or teammate, or to destabilise their defensive shape.

Progress with an Advantage

This last principle is a culmination of those before it and talks about the decision the team and individual players have to make about progressing the ball forward. The players need to identify individual situations on the pitch, recognise if they can create a superiority over the opposition players and then progress the play forward. In a situation where no superiority is visible, the team can recycle the ball in an attempt to destabilise the opponent and create an advantage.

Advantage: A good build up is one in which the team enters the opponent’s half with a superiority. This increases the chances of the attack leading to a goal-scoring opportunity.

Sub-principles

-

-

- Ball Circulation: Players circulate the ball in an attempt to destabilize the opposition shape and open spaces to attack.

- Creating Multiple Options: Supporting players need to be positioned in all directions around the on-ball player. Each option provides a different advantage, for example, passing back can help push the opposition further up the field, thereby creating space between the lines.

- Emergency exit: In a situation where the team is unable to progress the ball forward (due to high pressure or defensive shape), an extra attacker should drop to provide an extra passing exit option for the team.

- Visual Fakes: Players use visual fakes by positioning their body in a way that the defender expects and predicts the ball to be played in a certain space and starts moving accordingly. The player then takes advantage of that movement of the defender by moving the ball into the space vacated. Thiago Alcântara uses this sub-principle often while receiving the ball from the back. He wants the defenders to believe that he is passing the ball backwards, before turning quickly with the ball to face the opposition goal and progressing the play forward.

-

Along with these principles, the goalkeeper catching the ball opens new solutions for the team to build up their attack. This is a transition moment of the game as it is the end of opposition’s attack. They are usually disorganised and the goalkeeper has a range of options in front of him.

He can roll the ball to a player near him, throw it to a player in space or kick it long to initiate a counter attack for the team. It is difficult for the opposition to predict the attacking team’s next move and can be a weapon if used in a planned manner.

With all these principles being considered, it is important to remember that the players on the field have to deal with a dynamic opponent whose movement cannot be recreated with a hundred percent accuracy. So, it is more important that the players learn how to recognise and interpret live situation well and apply the correct solution to progress, as compared to working on rigid set patterns.

Patterns

While every build–up moment that a team creates is different from the other and improvised based on the idea of the coach, strengths and weaknesses (quality) of players available on the pitch and the league in which the team is participating, there are some common patterns that emerge under which those actions take place. The innovation usually occurs in how they work to recreate these patterns to achieve success.

Building Play in One Area of the Pitch to Create Space

When utilising this pattern, the aim of the attacking team is to attract opponents to one part of the pitch to create space in another. This can be done horizontally (zones) or vertically (thirds). Horizontally, the team can switch attack across the wide zones of the pitch (switch from zone 1 to zone 5), the alternate zone (zone 1 to zone 3 or zone 2 to 4) or adjacent zones (zone 1 to zone 2 or zone 3 to zone 4).

Vertically, the attacking team can entice the opponents to press them in their defensive third, thereby pushing the defending team forward and creating space either behind their defensive line or vacating space in the midfield third (while occupying the defensive and attacking third) creating space between the lines.

Using the Third Man: Pass or Run

A third–man pass or run is a fundamental pattern used by teams to achieve multiple objectives. Both these sub principles help the team create superiorities and progress up the pitch. It can be used to switch play, create overloads, break the press of the opponents, etc.

Creating Overloads To Progress: Wide or Central

The idea of this pattern is to move the ball forward by creating numerical superiorities in that part of the pitch. The team may use this pattern to safeguard progression of the ball and have players to counter-press in case of ball loss. Overloads can also be used to create space in other parts of the pitch.

Dummy Runs To Open Passing Lines

A dummy run adds an element of unpredictability to the team’s build–up play. It is defined as a movement made by an attacker off the ball with the intention to destabilise the opposition defensive shape and press. This pattern is highly effective against opponents that press with a ‘man–to–man’ system.

Conclusion

To conclude this piece, we hope you are able to take something from this into your training and game model. Our aim is to provide you with ideas that can make your team build up using the goalkeeper with greater effectiveness (reach the opposition half with an advantage). The sport is constantly evolving and we are sure there will be new methods/patterns that will see build up play change in the next few years.

It’s only a matter of time before Guardiola or a different coach comes up with something totally revolutionary that we haven’t seen before. Something we find extraordinary is the way some teams (Ajax / Manchester City) allow their goalkeeper to advance higher up the pitch to attract opponents in order to generate numerical superiority. This could be something to keep an eye out for in the future as it could be the next evolution in this sphere.

By: Saksham Kakkar and Dipankur Sharma

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / Jean Catuffe – Getty Images