From the Board to the Pitch: What Football Can Learn from Chess

You play football with your mind, and your legs are there to help you. – Johan Cruyff.

The above quote was uttered from football’s seminal leader, the unofficial king of the modern game, Johan Cruyff, and it may just be the most important of his innumerable, incessantly quoted adages.

If we take the great Dutch master at his word, and indeed look at football as a game of the mind, it only follows logically that it should draw inspiration from mind games across history, and what better place for the sport to start than by studying the most well-known and most popular mind game of all: chess.

After all, for a manager, the football pitch is nothing more than a large chessboard, upon which they place their pieces, manipulating them and manoeuvring them in battle. In this piece, we will have a look at three basic chess tactics and principles and how they have been used in football.

1. Domination of the central area

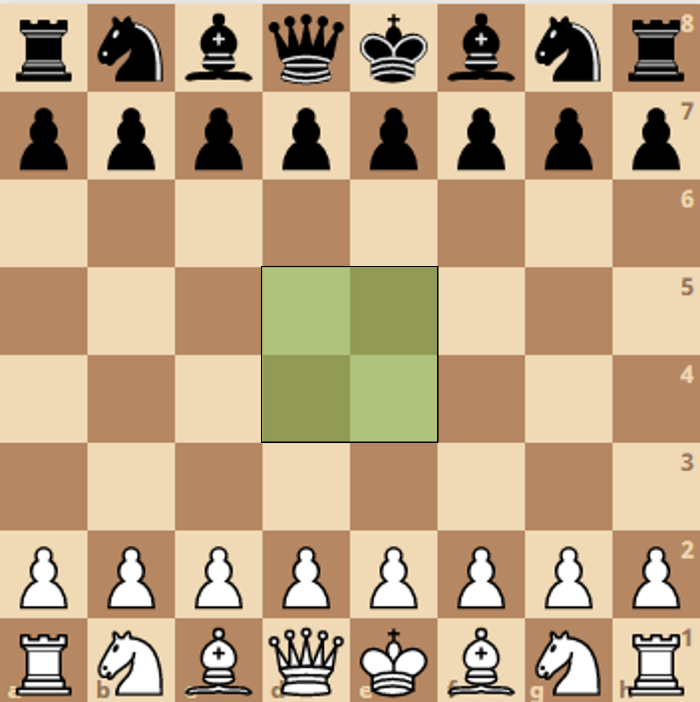

In chess, domination of the central squares, e4, d4, e5 and d5 (highlighted in green) is considered paramount to establishing control of the board. The more pieces one has attacking those squares helps ensure superiority and gain a foothold in that area.

Football is not dissimilar in this sense. Controlling the centre of the pitch is often one of the most important parts of any tactical plan. This can be done is a variety of ways, but here’s a look at just two examples, from a couple of the best tactical minds today; Jürgen Klopp and Pep Guardiola.

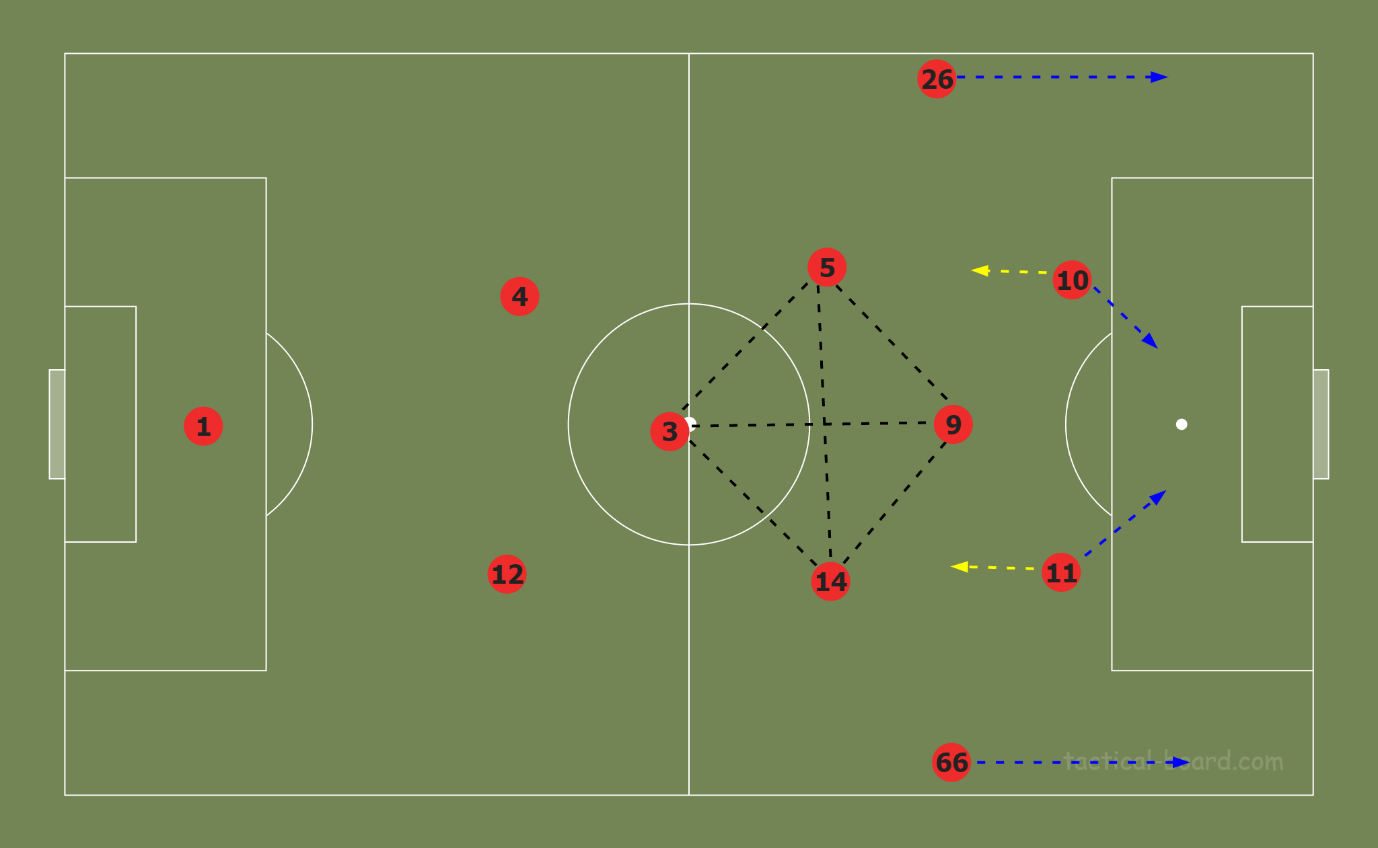

Jürgen Klopp’s Liverpool

It’s well known that most of Liverpool’s chance creation comes from the wide areas in the form of their full-backs, Trent Alexander-Arnold and Andrew Robertson pushing high and wide. However, the reason they are able to achieve this is through their domination of the central areas, which creates space out wide for the full-backs.

Liverpool’s 4-3-3 shape becomes a 2-3-5 in possession, with full-backs pushing up and the wingers coming inside. This front 5 then becomes staggered, rather than flat, with Roberto Firmino (9) dropping deep to join the midfield, creating a 4-man midfield.

This ensures that Liverpool will almost always have at least a man advantage in the middle. It is also difficult for opposition defenders to track his run, given that Mohamed Salah and Sadio Mané (10 & 11) are looking to make diagonal runs into central areas. A potential counter to this strategy is to go man-for-man with a midfield diamond, but teams are wary to employ such a strategy for fear of leaving the wide players open.

This effective block of 6 players in an advanced central area thus helps create space for the full-backs, who are reliable creators of high-quality chances.

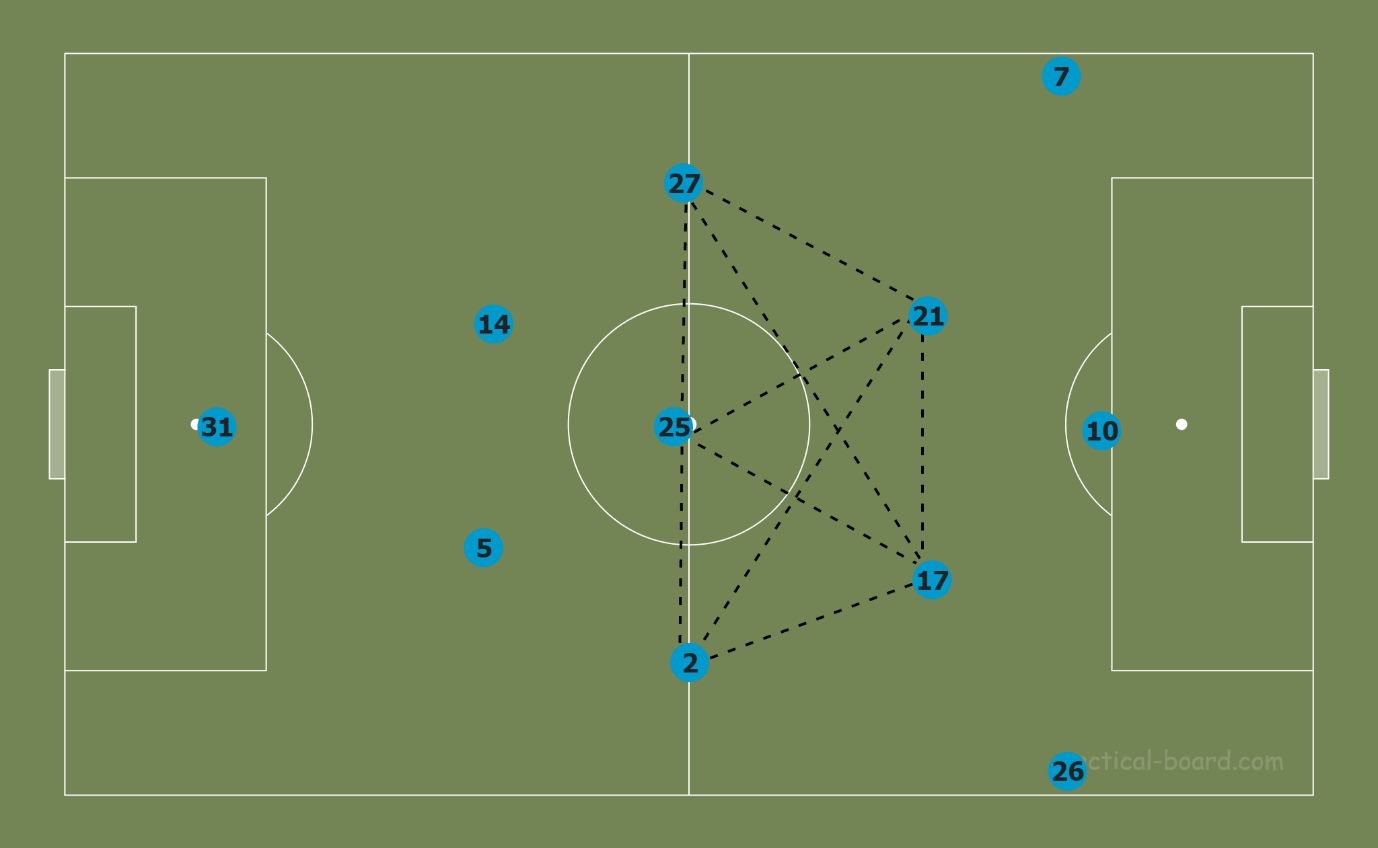

Pep Guardiola’s Manchester City

While Liverpool push their full-backs high and wide, with the wingers almost playing as strikers, Manchester City and Guardiola do the opposite. Very often, we see that City’s full-backs, Kyle Walker and João Cancelo (2 & 27) tuck into the midfield area, while the wingers hug the touchline, looking to stretch the opposition defence, essentially transforming from a 4-3-3 to a 2-3-2-3 in the build-up phase of play.

Another key difference between the two teams here is that while Liverpool look to create the central superiority high up the pitch, City do it a bit deeper, to draw the opposition onto them before cutting through. That 5-man midfield that has been created can constantly circulate the ball before finding an opening to progress it forward.

Of course, there are other ways to control the centre, even for less possession-dependent sides. A side like Burnley, who sit deep and narrow, forcing their opposition out wide, are controlling the centre even without the ball because they know that their defenders are well-equipped to deal with deliveries from the wide areas.

2. Pinning

The above picture highlights the basic concept of a pin. The white bishop is threatening the black knight, which cannot move as that would lead to the king being in check. So, the bishop has essentially ‘pinned’ the knight to that square.

While there is no direct footballing analogue for the pin, the concept is extremely useful in its application, especially when a team is pushing forward on the break.

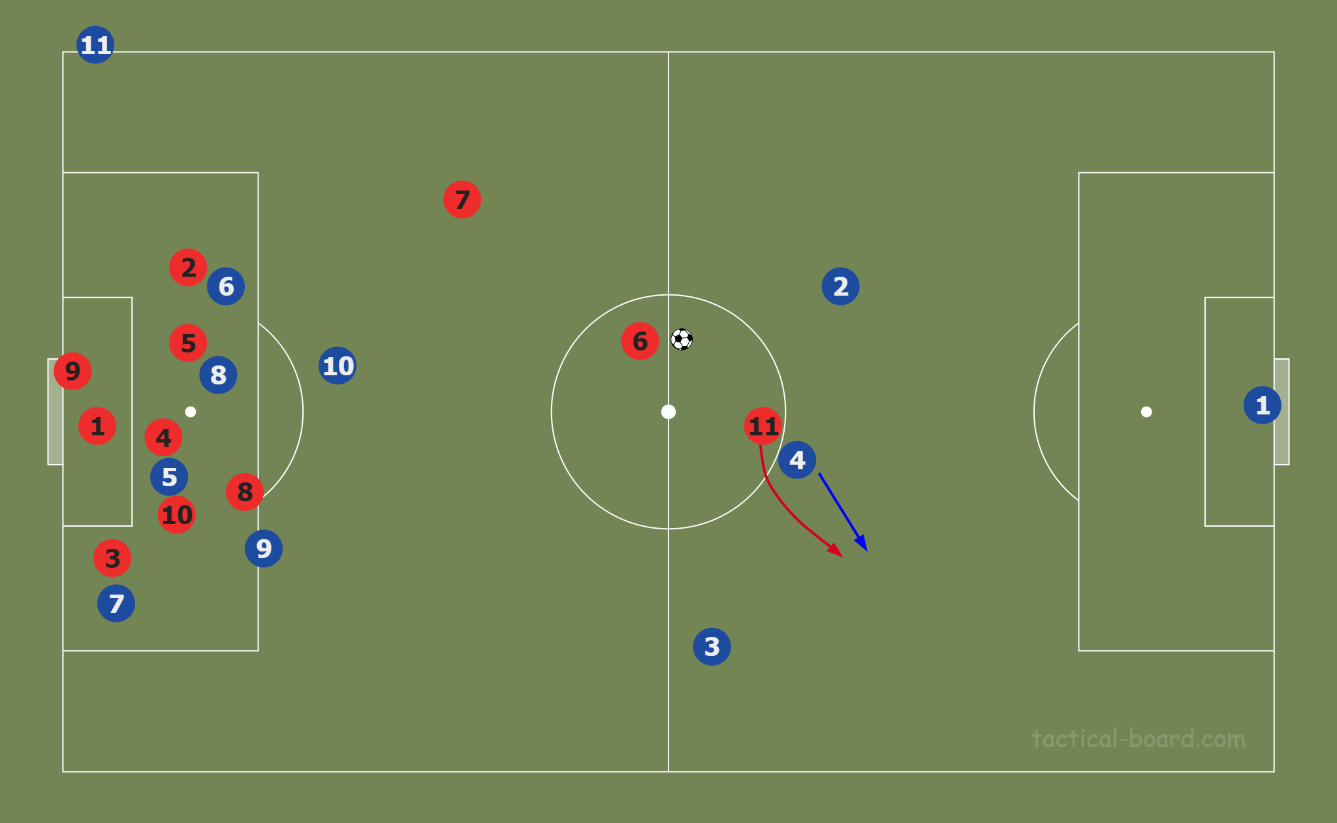

In the above situation, the red team has just cleared the blue team’s corner, and are now looking to launch a counter-attack, with number 6 carrying the ball forward. In this scenario, the red number 11 has an extremely vital role to play. He needs to choose which direction to make a run in, and the best decision would be to make the one indicated by the red arrow.

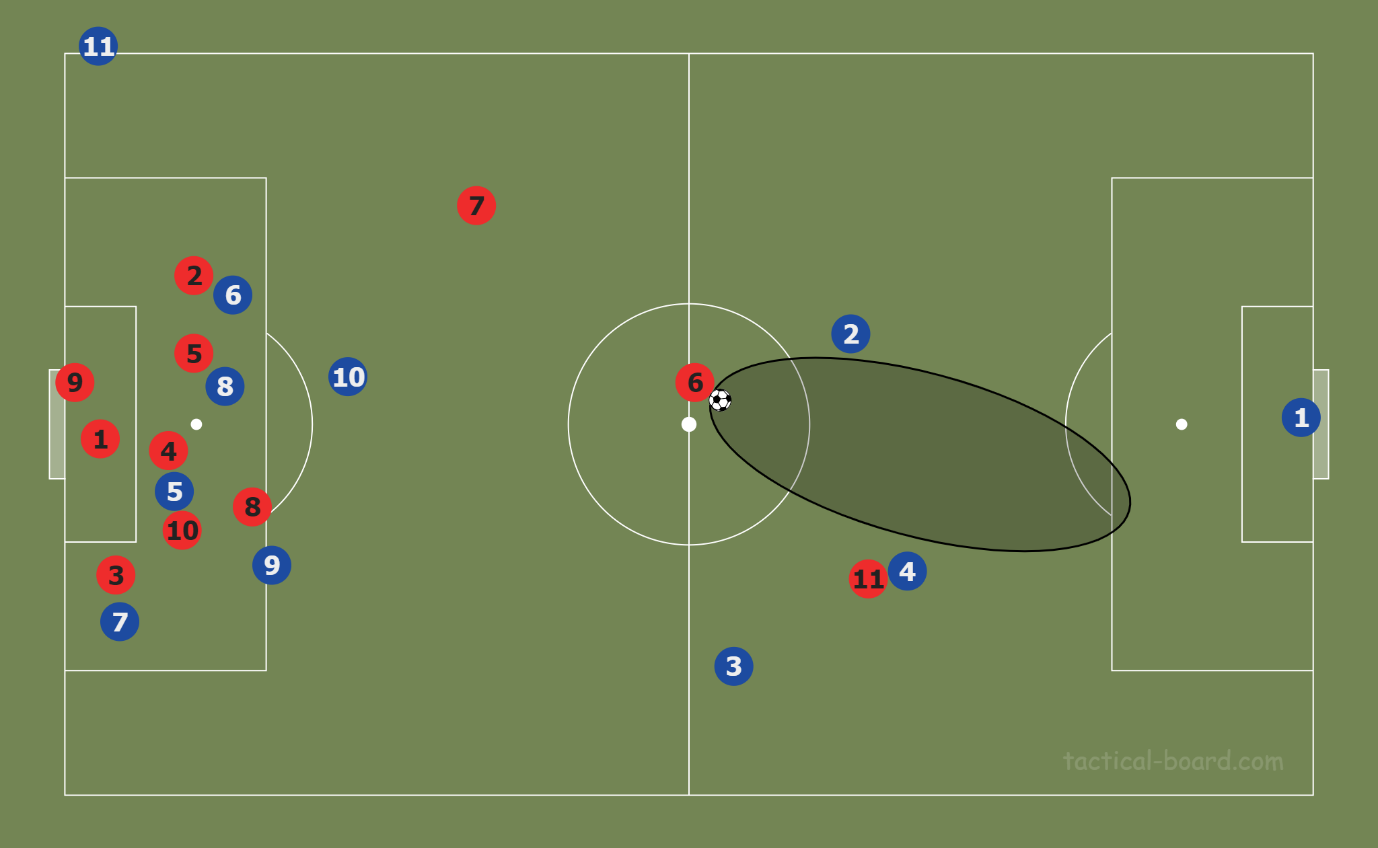

This will enable him to take the blue number 4 with him, as he cannot be left free. Even if the pass does not come, it opens up a dribbling lane for number 6, shown below:

In this instance, as the blue 4 cannot move away from the red 11, thus leaving him free, he has basically been pinned to cutting off a specific avenue of attack, which is the fundamental concept of the chess manoeuvre.

3. Forking

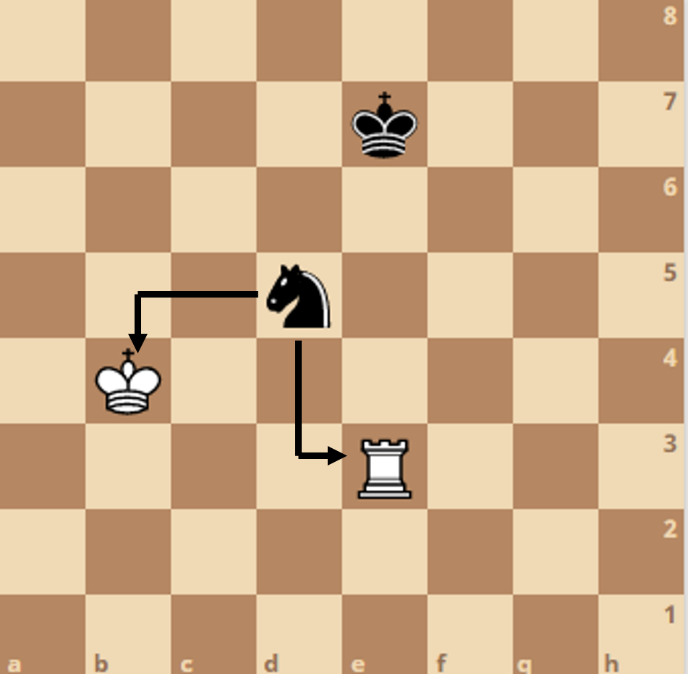

The concept of forking is a weapon that is often used in chess to force one’s opponent into making a difficult choice, or to ensure the capture of an opposition piece, as illustrated above. The black knight is attacking both the king (placing it in check) and threatening the rook at the same time.

In this case, white has no choice but to move the king out of check, leading to the loss of the rook. In another position, this knight could be attacking, say, a rook and a bishop simultaneously, in which case white would have to choose which piece to save and which one to sacrifice.

This is something we’ve seen before; in Guardiola’s all-conquering Barcelona. It isn’t immediately evident, but the consistent creation of passing triangles and midfield overloads is an example of the concept of the fork being applied practically.

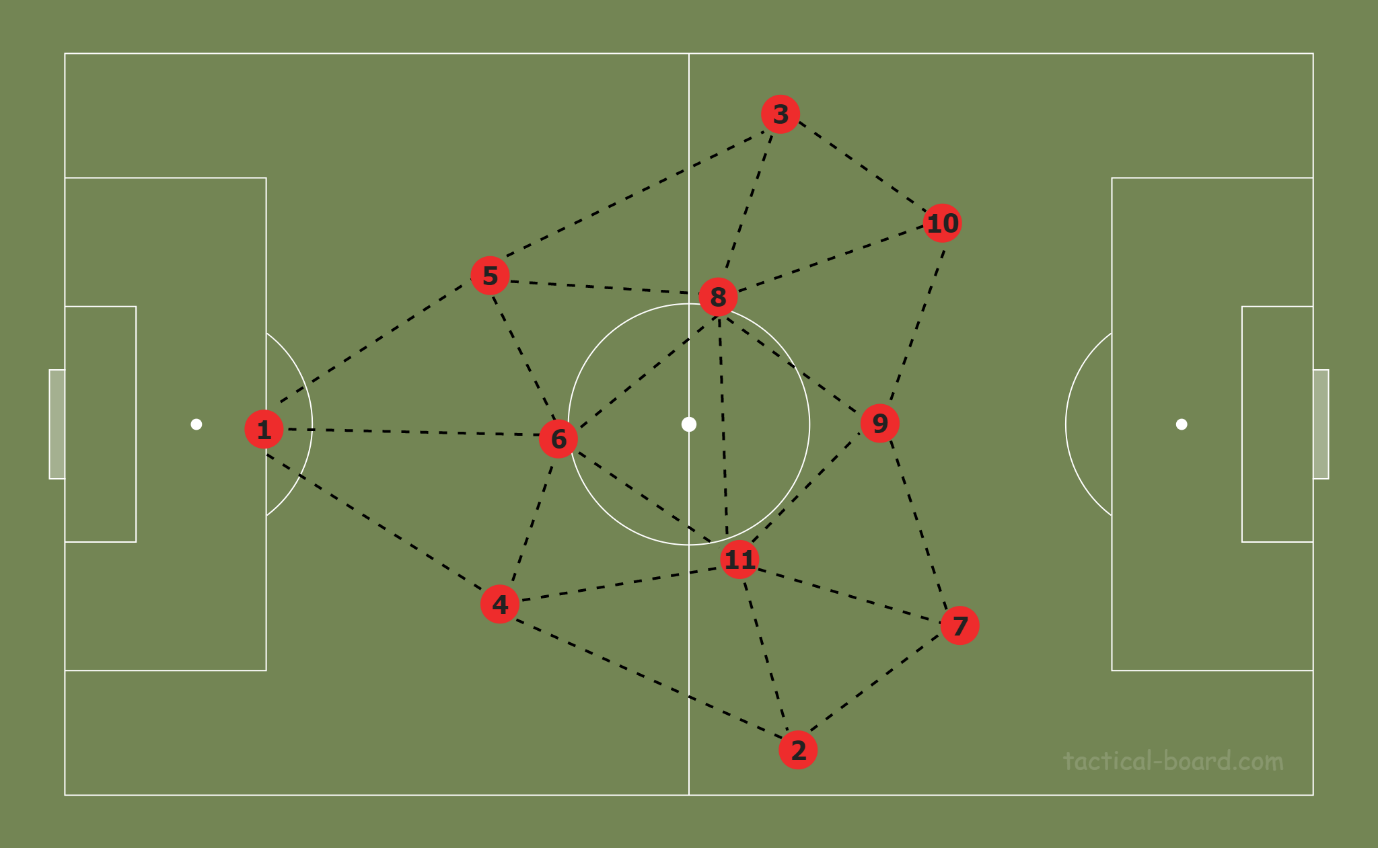

This was Barcelona’s general build-up shape under Guardiola. The integration of the goalkeeper as an outfielder and the positioning of the players across the pitch (in particular the number 6 dropping between the centre-backs, the number 9 coming short and the full-backs advancing high) enabled this team to create triangles all over the pitch, with the most potent ones being those out wide and the central one formed by numbers 8, 9 and 11, who were usually Xavi, Andrés Iniesta and Lionel Messi.

This system ensured that the player in possession of the ball always had at least two short passing options, which is not dissimilar to how the fork works. With the two avenues of attack available, opposition defenders would have to choose which player to close down, leading to the other one being free to receive the ball.

Again, this particular system is not the only way in which a fork can be used. Coaches can of course choose to try and create specific scenarios in specific areas of the pitch, such as in the defensive or attacking third, depending on whether they want to play out from the back or want their team to be more clinical when it comes to the final ball.

Going Forward

The three theories outlined here are merely a drop in the ocean that is the game of chess. There are countless other plans and strategies that can be adapted into football. This article should probably be treated as a primer of sorts, a piece to pique the interest of enthusiasts and those far more well-versed in both these disciplines than this writer.

To conclude, here is a quote, taken from Sun Tzu’s The Art of War, which speaks, in particular, to the dynamism of both chess and football:

Therefore, just as water retains no constant shape, so in warfare there are no constant conditions.

By: Rahul Iyer

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / Tornado Studios