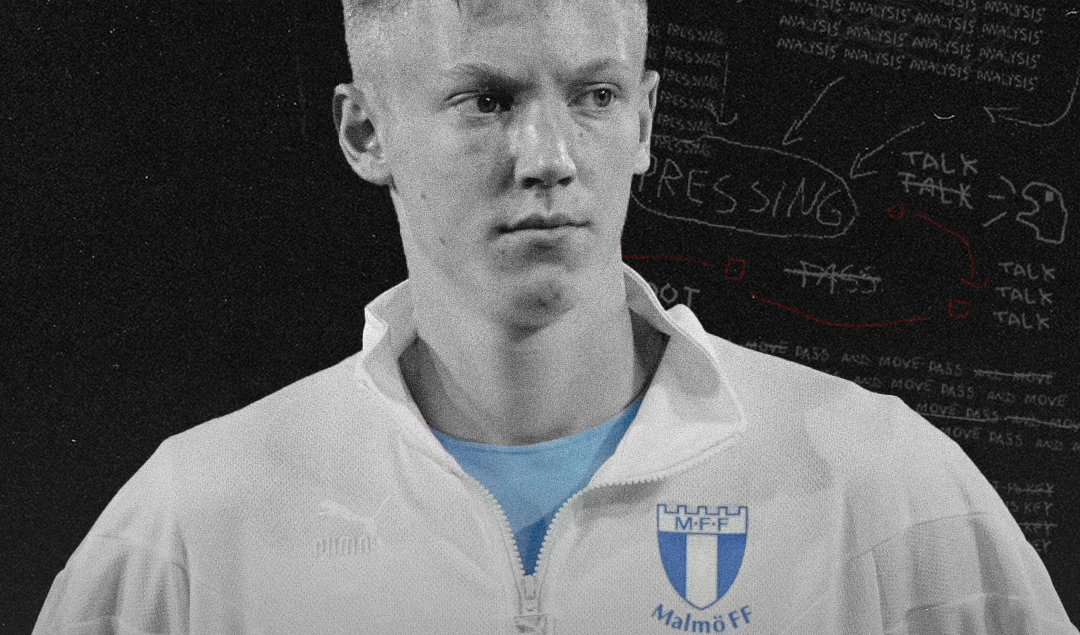

Henrik Rydström and Malmö FF: The Art of Relationism in Scandinavian Football

Football, like the tangled roots of a rainforest, is often misunderstood by those who only skim its surface. Within the game’s deeper layers, however, lies a complex network of influences, philosophies, and identities that defy easy categorization. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the rise of Relationism within European football — a philosophy birthed in the streets and pitches of Brazil but one that has found new life in the most unexpected corners of Europe.

The evolution of football is often narrated as a linear journey—progressing from the tactical rigidity of early formations to the fluid, complex systems of the modern game. But viewing this evolution as a straightforward path misses the intricate, almost chaotic weave of ideas that have shaped it.

Bound by Tactics: The Enigma of James Rodríguez’s Unseen Brilliance

Like the entangled vines of the Amazon, football’s development is a story of convergence, where distinct philosophies and identities intertwine to create something richer. Relationism, a philosophy that sees the game as a dynamic interplay of relationships rather than rigid structures, is one of those tangled vines.

Born in the heart of Brazil, Relationism is more than just a tactical approach; it’s a reflection of the country’s broader culture—an expression of its improvisational creativity, its rhythm, and its deep sense of connection. It’s football played like samba, where the beat dictates the movement, and the movement dictates the strategy. In Brazil, football is more than a sport—it’s a language, a form of expression that speaks to the heart as much as to the mind.

Yet, as with any idea that travels beyond its place of origin, Relationism has morphed as it crossed the Atlantic. The Europe that greeted Relationism was not the same as the Brazil it left behind. Here, it encountered a football culture steeped in discipline, in structured systems of play that prized order and efficiency.

But rather than being diluted, Relationism has found new life in Europe, fusing with local traditions and philosophies to create something distinct—something that both honors its Brazilian roots and adapts to the demands of a new environment. In Brazil, Relationism was born out of necessity. The country’s vast economic inequalities meant that many players honed their skills not in formal academies, but in the streets, where improvisation and creativity were not just valued, but essential.

This is a philosophy that celebrates the unpredictability of football, that sees the game not as a series of set plays, but as a fluid, ever-changing dance. It’s a philosophy that understands that the best-laid plans often fall apart in the heat of the moment, and that true mastery lies in the ability to adapt, to find new solutions on the fly.

Fernando Diniz, one of the most prominent advocates of Relationism brought this philosophy to the fore with his work in Brazilian football. His team, Fluminense, played with a fluidity and creativity that seemed almost anarchic but was, in reality, deeply rooted in a shared understanding of the game.

In Diniz’s system, every player is a potential playmaker, every pass a potential dagger through the heart of the opposition. It’s a style that thrives on unpredictability, on the idea that the best way to create space is not through rigid structure but through the constant movement and interaction of players.

When Relationism began to creep into European football, it did so quietly, almost unnoticed. But in Malmö FF, a club known for its tactical discipline and defensive solidity, the introduction of these Brazilian concepts created a fascinating hybrid—a team that combined the best of Scandinavian pragmatism with the free-flowing creativity of South American football.

A Talent Strangled by Triangles: The Tanguy Ndombele Conundrum

Malmö FF has always been a club that prides itself on its ability to adapt. From its early days dominating Swedish football to its ventures into European competitions, Malmö has constantly evolved, integrating new ideas and philosophies into its core identity. But the introduction of Relationism was something entirely different—a shift not just in tactics but in the very way the game was understood.

The catalyst for this change was the appointment of Henrik Rydström, whose name is whispered with some reverence in football circles. Rydström, who had cut his coaching teeth in the cauldrons of South American football, brought with him a philosophy that was both radical and revolutionary.

He spoke of the “escadinhas”—a concept of staircase passing that prioritized short, sharp exchanges between players, designed to disorient the opposition and create spaces in the most congested areas of the pitch. Under his guidance, Malmö began to play with a new rhythm.

The rigid lines of Scandinavian football were softened, replaced by a more fluid, interconnected style. The team pressed high, but not in the traditional, man-marking sense. Instead, they pressed as a unit, moving together like a wave, with each player understanding their role in the system.

The ball moved quickly and often horizontally, as players looked to create overloads on one side of the pitch, only to switch play suddenly and exploit the space on the opposite flank. This was Relationism in its purest form — a style of football that thrived on chaos, on the idea that the best way to control the game was to let it flow naturally, allowing the players to express themselves and make decisions based on their own instincts and understanding of the game.

One of the most intriguing aspects of Malmö’s transformation was the way in which Brazilian concepts were integrated into the team’s playing style. The “escadinhas” and “Toco y Me Voy” (one-two) became a key feature of Malmö’s attacking play, with players constantly looking to create short passing triangles and diamonds, moving the ball quickly and with purpose. But it wasn’t just the passing that changed—Malmö’s movement off the ball became more dynamic, more unpredictable.

The concept of jogo bonito or the beautiful game became a guiding principle for the team. It wasn’t just about the aesthetics of the game; it was about playing with joy, with freedom, and with an understanding that the game is as much about creativity as it is about tactics.

This was evident in the way Malmö’s players expressed themselves on the pitch—whether it was a no-look pass, a cheeky backheel, or a perfectly timed dribble, there was a sense that the players were enjoying themselves, that they were playing with a smile on their faces. But perhaps the most significant Brazilian concept that influenced Malmö’s play was the idea of “ginga”—a term that is difficult to translate but is often associated with the unique swagger and rhythm that Brazilian players bring to the game.

Ginga is about more than just skill; it’s about attitude, about playing with a certain flair and confidence that can intimidate opponents and inspire teammates. In Malmö, this translated into a team that played with a newfound swagger, a belief that they could take on any opponent and come out on top.

From a tactical perspective, Malmö’s new identity is a fascinating blend of old and new, of European pragmatism and Brazilian creativity. Defensively, the team remains solid, with a well-organized backline and a disciplined midfield that works tirelessly to close down space and win back possession. But it is in attack where Malmö truly comes alive.

The team’s use of Relationism allows them to dominate possession and create overloads in key areas of the pitch. By moving the ball quickly and with purpose, Malmö is able to break down even the most stubborn defenses, creating chances through intricate passing combinations and intelligent movement off the ball. The players’ understanding of their roles within the system is crucial to this success—each player knows when to press, when to drop off, when to make a run, and when to hold their position.

But it isn’t just about the play; it was about the mentality. Malmö’s players embraced the Brazilian concepts with open arms, and this was reflected in their performances. There was a sense of freedom and joy in the way they played, a belief that they could express themselves on the pitch without fear of making mistakes. This was a team that played with confidence, with swagger, and with a deep understanding of the game.

As Malmö’s journey continues, the question remains: can this hybrid identity of Relationism and Scandinavian pragmatism succeed in the long term? The early signs are promising—Malmö has enjoyed success both domestically and in European competitions, and the players have fully embraced the new philosophy. But the true test will come in the years ahead, as other teams look to adapt and counter Malmö’s unique style of play.

One thing is certain: Relationism has left its mark on European football, and Malmö FF is at the forefront of this revolution. The team’s blend of Brazilian creativity and Scandinavian discipline has created a new identity, one that challenges the established norms of European football and offers a glimpse into the future of the game.

By Tobi Peter / @keepIT_tactical

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / DeFodi Images