How Losing Leroy Sané Changed Manchester City’s Attacking Dynamics

Pep Guardiola’s Manchester City set English football alight in the 2017/18 campaign, becoming the first Premier League team to record 100 points, whilst also breaking a host of records: most wins (32), most goals (106), most points ahead of second (19), and best goal difference (+79). The following season, City completed an unprecedented domestic quadruple, narrowly edging Jürgen Klopp’s Liverpool to the Premier League title with 98 points.

However, after a historic two-year spell, the past 18 months at the Etihad have been far more reminiscent of Guardiola’s challenging first season in England than either of the aforementioned campaigns. Whilst City did manage to win the EFL Cup in March, they were eliminated in the FA Cup semifinals by Arsenal and finished 18 points behind Liverpool in the 2019/20 season. Today, they sit 5th in the Premier League, albeit only five points behind Klopp’s first-place Reds.

There’s no single reason to explain this decline: Vincent Kompany’s departure, the aging of key players such as Fernandinho and Sergio Agüero, and a natural decrease in fitness levels after record-breaking dominance have all played a role. But one of the biggest factors has been the departure of Leroy Sané to Bayern Munich.

The German winger came close to leaving Manchester in the summer of 2019, but after tearing his ACL in the Community Shield against Liverpool, his move to Bayern Munich collapsed. Sané would make just one brief appearance against Burnley before rejecting a contract extension and forcing a move to the Bavarian giants for an initial fee of €45 million rising to €60 million with add-ons, arriving on a five-year contract.

City, in turn, purchased Ferran Torres from Valencia for €23 million, and while the 20-year-old has provided 7 goals and 2 assists in 18 appearances, he has been unable to replicate the extraordinary heights that Sané showed during his first three seasons in Manchester. Sané’s unique profile played a vital role in City’s attacking dynamism and width, and his absence has had a sizable impact on Guardiola’s strategy going forward.

From 2016 to 2019, City’s most common chance-creation mechanism was a drilled cross or cut-back from the half-spaces into and around the 6-yard box, consistently creating high quality opportunities. Paramount to its execution were three factors; deep vertical infiltration, use of the half-spaces and using wingers on their stronger side.

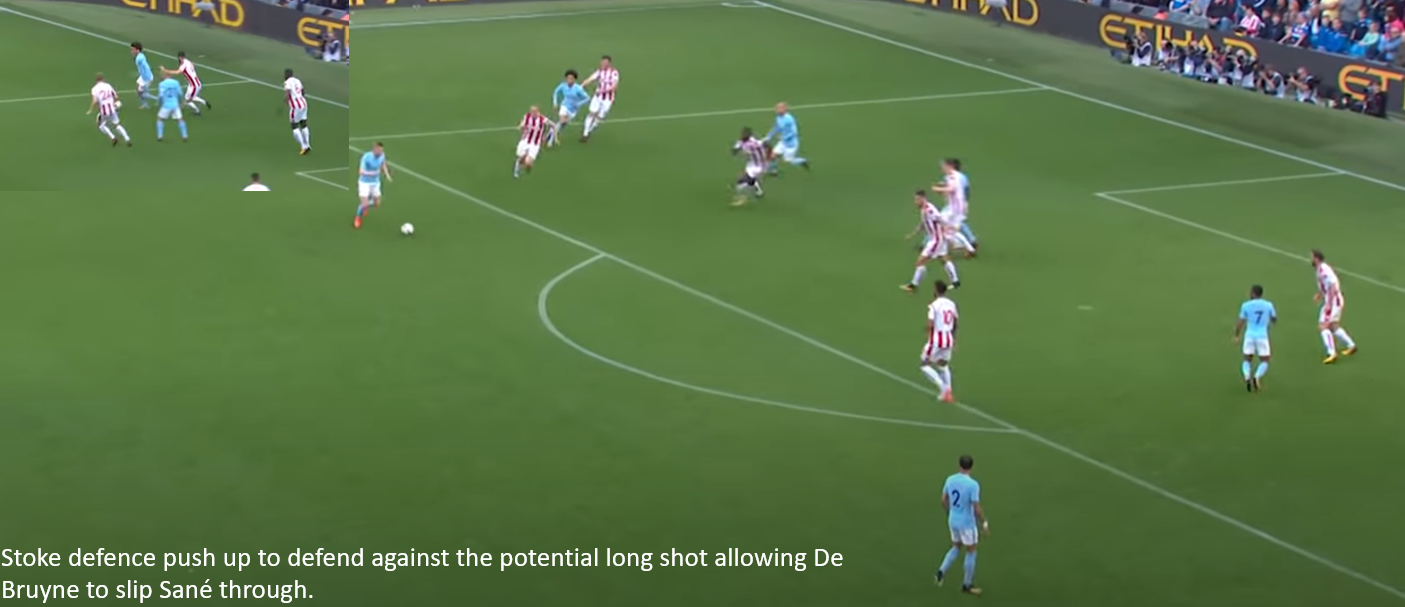

In order to successfully implement this maneuver, City would need to provoke quick, vertical transitions by exploiting the opponent’s defensive game-state of retreat. These transitions were typically prompted by an incisive pass in between defenders which was effective because how quickly the ball can move to gain territory, however a dribble by one of the wingers can also force a retreat.

This disorganises the opponent’s defensive structure through introducing new space. The introduction of new space forces compensations defensively as they become focused on preventing the player on the ball being effective and protecting the deepest available space, which is constantly changing due to the runner on the ball progressing potentially until the touchline.

The defending team is not defending collectively because of the provoked disorganisation, with each individual seeking to limit the highest quality chances which leads to many players committing deep. This generates space for cutbacks as the opposing defence lack staggering to cut passing angles and mark at multiple depths in addition to causing a highly congested box which can be exploited through drilling a cross. That is moreover working under the presupposition that they did recover, which was not always the case.

This is as limiting the highest quality chances could be impossible after the pass into the runner in the half-space. This was because of due the automatised nature of the play, resulting in the action of the through ball to or dribble by the near side winger implying a subsequent action to the player at the far post to be prepared to accelerate and perhaps linger in an offside position which will quickly be made onside which gave them the positional superiority to score from close range.

The half-space is of paramount importance in this scheme because of its positioning. It is not too wide as to leave time during the transport of the ball for space to be better interpreted by defenders. Increased time could potentially allow the opponent to restore a semblance of order postionally through better staggering which would place them in better positions to prevent multiple players receiving.

Additionally, central areas can typically become too congested to be used effectively for chance creation as cutbacks are more easily cut out due to the compact positioning of the opponent reacting despite being in the reactive and compensatory state of retreat. While the player receiving has less time to interpret his surroundings or respond to a drilled cross.

It is important to note not all the drilled crosses originated in the half-space, with players such as Benjamin Mendy and Kevin De Bruyne providing a threat out wide. The primary concern was to ensure City maintained the initiative offensively by limiting the inertia period which allows the opponent to reconfigure. The key component was forcing the defensive state of retreat to create space to exploit the opponent’s lack of organisation.

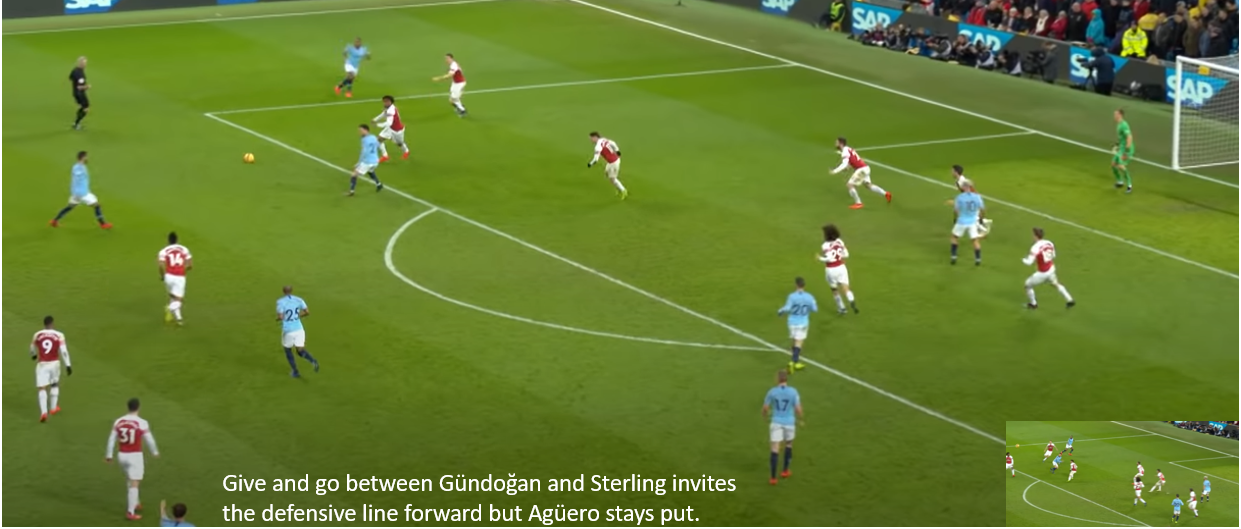

Another common facet of play to create the space for these types of chances was the give and go. The winger, in a more advanced position would play the ball backwards into the half-space and make the run for the vertical pass either in between or over the defenders. This would have the effect of moving the opposing team’s defensive line as they pushed forward to remain compact while applying pressure to the player in possession.

This had the potential to catch the Manchester City player making the run offside, however, because of their proficiency in completing the actions quickly and accurately they often succeeded at exposing the space in between the lines. The City player would often have time because of the differing movements created by the initial backwards pass as the runner’s momentum was always forward compared to the pivoting defenders.

The juxtaposition of backwards/forwards movement would manipulate the positioning of the defenders granting space. Additionally, because of the automatization, the centre forward would often not respond to the defences initial push forward as they would later be played onside by the advanced positioning of the winger which grants them space to receive the cross due to having an extra yard on the defender. This is facilitated through the additional space granted by using wingers to vertically stretch the opponent.

In essence, the wingers going deep with the ball often drew multiple players as exposing players of Sané and Raheem Sterling’s quality to 1v1 duels was dangerous. This meant the attacking midfielder in the half-space had time to receive from a pass back, drawing players forward creating space for the winger to subsequently invade. David Silva and De Bruyne could be trusted to exploit the openings.

Despite being the defining characteristic of the incredibly successful 2017/18 and 2018/19 seasons, the use of deep half-space runs to play the ball centrally has become less common because of the loss of Sané. The German allowed City to play two wingers on the side of their stronger foot, which is more suited to quick crossing actions, particularly when generating power is a crucial factor as defenders seek to close off space inside which generates time.

The direct path deep and wide is not as attractive when playing on the ‘weaker’ side because it becomes increasingly difficult to cut inside when going deep as the opponent looks to show you onto your weaker foot. If the opponent attempted this on Sané it would grant him direct access to deep central areas of the box allowing for a cut back.

The alternatives were equally unattractive as engaging posed the threat of further worsening defensive structure because of the necessity to compensate should they be beaten, or it could have produced a penalty, both of which were probable against a player with the close control and speed of Sané. However, allowing progression made it increasingly difficult to cover space and made the drilled cross more dangerous.

Thus, this half space dynamic created many unattractive options not available to an inverted player. An inverted player can successfully horizontally stretch then seek to move inwards with the counter movement of an overlapping fullback, however because of the congested nature of deep central regions this is more difficult to pull off as the player progresses.

Inverted players find it more difficult to vertically stretch opponents in deep areas due to the congested nature of play during that game-state, which is one frequently faced by Manchester City, which has resulted in decreased penetration.

Photo: Twenty3/Wyscout

The above diagram demonstrates the average positions from Manchester City’s team from 2017/18 to 2018/19. Despite being a midfielder by trade, Fabian Delph operated as an ‘inverted left back’ whilst John Stones partnered Aymeric Laporte in defense. Fernandinho, De Bruyne and Silva composed one of the most fearsome midfield trios in Premier League history, whilst Ederson’s ability on the ball provided a constant outlet in possession.

Riyad Mahrez has also become increasingly present in City’s starting XI, which influences dynamics significantly, as Sterling situates himself on the left to cut in and Mahrez places himself on the right to cut in. This means in-swinging crosses have become more common as a mechanism to infiltrate deep areas as Kyle Walker surges forward to provide a counter movement to drag defenders to create space for Mahrez.

These crosses are predicted to a greater degree on accuracy than the previous method where producing power was the critical element. The reduced power subsequently makes the job of the receiving player more difficult as rather than having the ball played laterally (perhaps slightly advanced but rarely to a significant degree) or behind it.

This means the forward must change body orientation to receive rather than being able to run forward consistently or drop slightly while maintaining roughly similar base positions. This typically means more time is required to move the ball into the 6-yard box to create chances quality comparable to the drilled crosses/cutbacks which grants the defending team more time to interpret space.

Photo: Twenty3/Wyscout

With Sané out for most of the season with a torn ACL, Guardiola turned to Mahrez in the right wing position with Sterling playing on the left flank during the 2019/20 season. Because of an increased proclivity to cut inside, City have struggled relative to previous seasons to penetrate deep through direct runners as the wingers preferred to move inwards directly rather than gradually through vertical movement.

This means they are less likely to force the state of defensive retreat as they are not stretching the opponent to the same extent. Walker and Mendy provide a threat overlapping down the flanks which still grants them the potential to cause similar situations.

However, they are typically wider in positioning making crosses less effective, and because it is no longer the primary method of chance creation it has become less effective as movements no longer carry the same implications as they did previously for City to have more of the initiative offensively. Moreover, qualitatively the threat they pose compared to Sané makes them much easier to handle defensively.

Another externality has been reduced freedom for the attacking midfielders as using Mendy makes City less inclined to invert the full back during build-up which occasionally requires a supplementary midfielder to support. This means they are less likely to be in the position to catalyse the deep half-space run and thus the trigger to the event is not present.

Additionally, the act of inverting can crowd the half-spaces meaning the midfielders have less space to operate in more generally as well as having fewer alternatives. The defensive problems have arguably been provoked by the change to attacking dynamics moreover because of the increased requirement for the full backs to attack meaning they no longer provide extra protection through their central compactness.

This explains the transition to the 4-2-3-1 as there is constantly a deeper figure to support build-up and De Bruyne as an attacking midfielder is less restricted to a specific flan, while having two holding midfielders grants additional protection when the full back(s) push forward.

This is not to suggest City are no longer an extraordinarily successful attacking unit as the diversification of chance creation makes them more difficult to prepare against. Positives such as De Bruyne being able to overlap Mahrez more frequently than he would Sterling have occurred. However, none of those methods in isolation are as effective as the half-space infiltration to cause a retreating defence which became synonymous with the two-time Premier League champions.

Since arriving in Bavaria in July, Sané has failed to show the same levels of performance that made him into a force of nature prior to suffering the ACL injury, with the German winger often being benched for Serge Gnabry and Kingsley Coman in 4-2-3-1. On the other hand, City have still not managed to find the magic and dynamism that Sané’s individual brilliance could produce on a consistent basis.

By: @mezzala8

Featured Image: @GabFoligno – Oli Scarff – AFP