How Spain Won the Women’s World Cup

On Sunday, August 20th, Spain won the Women’s World Cup. The victory was their crowning achievement and had been a long time coming for the team. It was also a product of their youth development, as victories in the U17 and U20 World Cups are a testament to the youth development of the Spanish players.

The World Cup victory also means that Spain is the first nation to hold all three titles at once. Spain also managed to win this tournament despite enduring turmoil, with most of it fostered and fomented by head coach Jorge Vilda and RFEF president Luis Rubiales, Here’s a look at how the various formations La Roja fielded during this tournament and how they were ultimately crowned World Champions.

The Early Proceedings

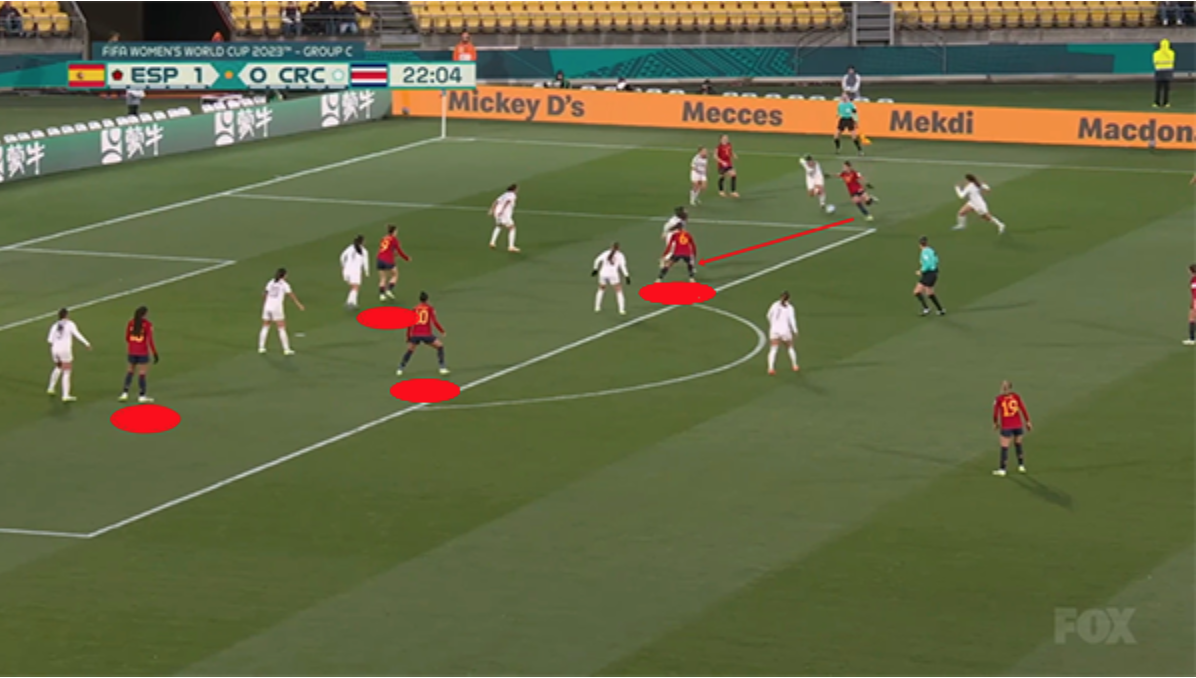

Spain started off the tournament rather brightly. They did so by dispatching Costa Rica by a score of 3-0 and then dismantling Zambia by a score of 5-0. Against these two teams, the Spanish would deploy a 4-3-3, which allowed them to not only maintain possession but also use their wide players to create scoring opportunities through overloads, overlapping runs, and making horizontal runs into the box. An example of this was during their group stage game against Costa Rica.

Once Spain progressed into the final third, Spain would compound matters by getting numbers into the box. They did this through a combination of Esther Gonzalez’s positioning and her runs at goal, and having Jenni Hermoso and Aitana Bonmatí positioned at the edge of the box for a cut-back or to pick up the loose ends.

While this strategy initially worked well against these two teams, as they didn’t provide much of a challenge for them, Japan would be a different story. The Japanese were able to halt Spain’s trajectory through a variety of ways. Japan deployed a 5-4-1 that morphed into a 4-1-4-1 at times. They also cut Spain’s passing lanes with intelligent pressing, compressing the midfield, and closing down space. As a result, Spain weren’t given the space they needed to play their passing game and forced Spain out wide.

The Japanese also made it incredibly difficult for Spain to cut through the lines and create overloads in those wide areas. The Nadeshiko became a literal wall that Spain could not play through. And whenever they tried to do so, they looked lost and out of ideas. Japan were quite disciplined in their approach to the Spanish, as their players instinctively knew when to step forward and press while the rest stayed back to maintain their shape.

La Roja’s insistence on playing short passes instead of long balls that might have switched the point of play also played into Japan’s hands, as it allowed them to intercept the ball and launch a quick counterattack. The tactics employed by Japan were similar to the way the Dutch Men played in the 2014 World Cup, where they also used a back five against Spain and hit them on the counter to devastating effect. Both teams would dismantle the Spaniards using this system.

Spain’s insecurity also hurt them in this game. For example, from this sequence from Olga Carmona, who initially wanted to drive forward but changed her mind and stepped back. This killed what could have been an attacking sequence from Spain, thus allowing Japan get back into their defensive shape. The original goal was to pull Japan out of shape to create attacking sequences, and the Spaniards failed at it.

Oftentimes, Spain looked like they were lost for ideas when they couldn’t play centrally. As a result, they lost the game 4-0. Although they would lose this game, and Carmona would experience moments of indecision throughout this game, she and the rest of the Spain team would eventually redeem themselves.

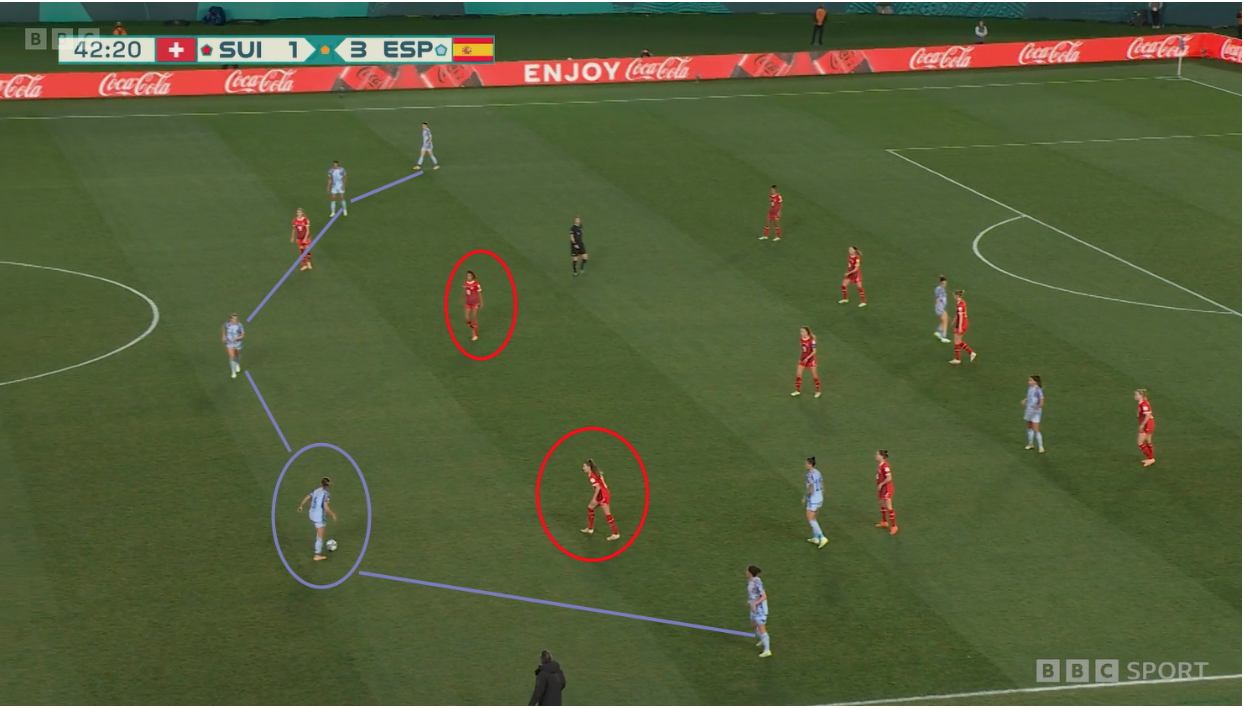

After losing to Japan, Spain advanced to the Round of 16 where they played against Switzerland. Unlike the Nadeshiko, the Swiss would not display the same defensive discipline. Instead, their 4-2-3-1 shape gave the Spanish the much-needed space they needed to play their game. In particular, Switzerland’s midfielders were isolated in the setup, and could not connect with their forwards or aid their defense much.

This then allowed Spain to play between the lines and to progress through the middle. There was a distinct lack of organization in the Swiss side, evident by how the defenders barked at the players in front of them for not getting into the game. The fault, however, lay more with coach Inga Gring’s tactics than them. Spain would probe and find space much as there were many holes in the Swiss defense.

The only flaw during the match for La Roja was a shaky back pass from Laia Codina that gifted the Nati their only goal. However, Codina would make up for this by scoring one of Spain’s five goals. Codina was also in the lineup in place of Ivana Andrés, who didn’t fare well against Japan.

Laia was one of the many lineup changes that coach Vilda made before the game. Most of those changes would stick with the team for the rest of the tournament. Aside from Codina, one of the players who was crucial to their victory was Aitana Bonmatí. Bonmatí’s close control touch of class has been crucial to Spain’s success, as the midfielder put on an absolute clinic with two goals and two assists against Switzerland.

After that game, La Roja went on to play The Netherlands. And it is against The Dutch that we finally see a Spain that’s learned its lessons. Like Japan, the Netherlands played a back five in a defense but where they differed from the Nadeshiko was by employing a 3-4-1-2/3-5-2 when building up play. The Dutch Women did not employ a rigid back five against Spain. It was a lost opportunity as they could have deployed the same tactics their male counterparts did when they dismantled Spain. The Dutch back three would give Spain room to operate and their players would make several runs behind their defense.

The Oranje also left a few players high up the pitch for a counterattack, most notably Lieke Martens and Lineth Beerensteyn. The fact that they didn’t track back to defend gave Spain space to play between the lines. And whenever the Oranje tried to press them, the Spaniards employed a variety of different ways to evade it. This includes playing in a more direct manner with long balls over the top.

As an example, while under pressure from an aggressive Dutch high press, Spain plays over their forward and midfield lines to Mariona Caldentey, who receives the ball under pressure. She then makes a long, forward pass to Alba Redondo who then shoots on sight. The Dutch respond by engaging a mid-press, but Spain still retains the ball.

Spain’s compact, offensive shape, where the players stayed close to one another, also allowed them to win the ball back quickly. This type of creativity allowed them to break out of the Dutch press and they would eventually win the game by a score of 2-1.

Spain’s Press Resistance

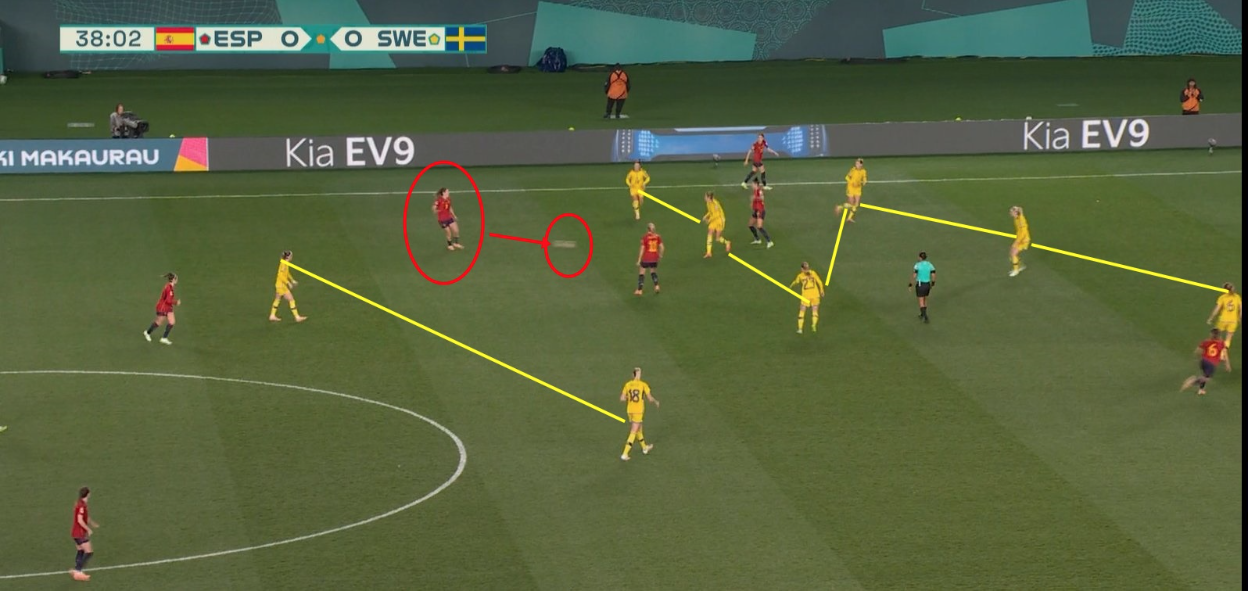

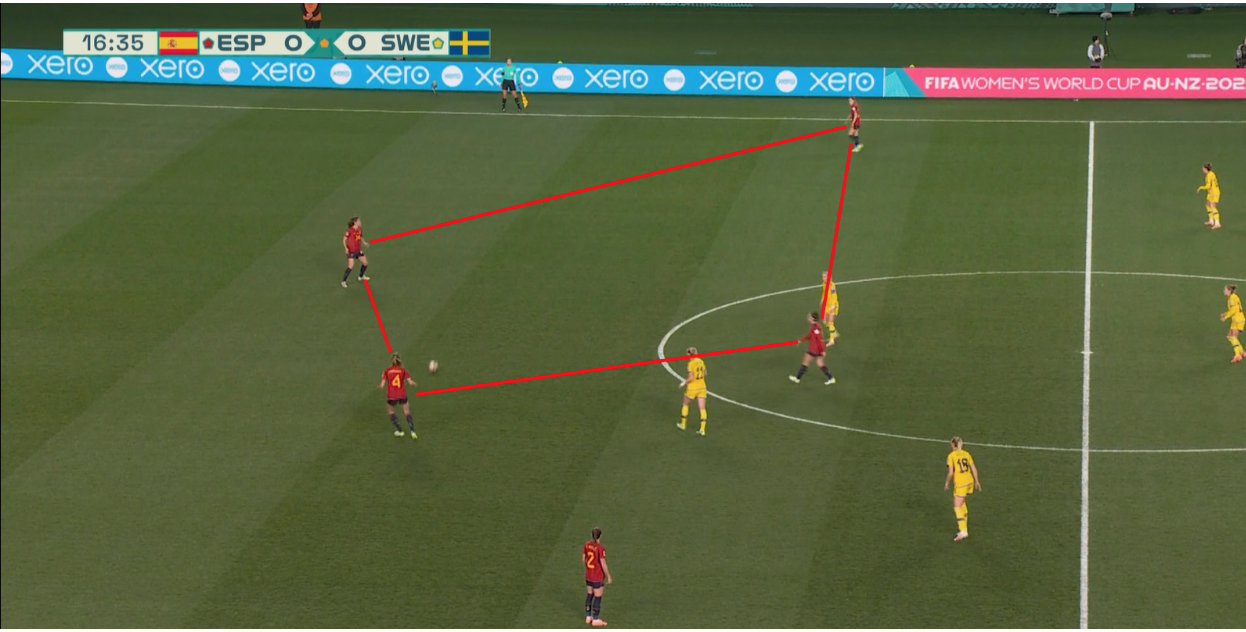

Spain’s press resistance would get them out of sticky situations against The Dutch. It would also help them out against Sweden. Sweden were more defensively disciplined than La Roja’s last two opponents. As an example of this, here’s how Sweden would move as one to deny Spain the chance to build up play through the middle.

(Sweden committing to one side of the pitch, Alexia breaks the lines with one pass)

Sweden committing players to one side of the pitch was an effective tactic, though it left them with one glaring weakness. Whenever they would shift to one side, they left the other side of the pitch open. Spain would exploit this by creating an overload switch of attack and having their players run into the free space to receive the ball.

The objective was to get Sweden to overload defenders to one side of the field through their passing and then play the long switching ball to that “weak” side and create a “numbers up” situation as they ran towards goal. Shifting the defense and forcing Sweden to overcommit players opened up channels for the Spanish players to run into.

The way the Swedes played was very reminiscent of how Antonio Conte set up the Italian Men against Spain in Euro 2016. Both teams’ coaches had their players move like a flock of birds to cut off the Spanish passing channels and disrupt their rhythm. However, Italy would emerge victorious from their game. Sweden would not.

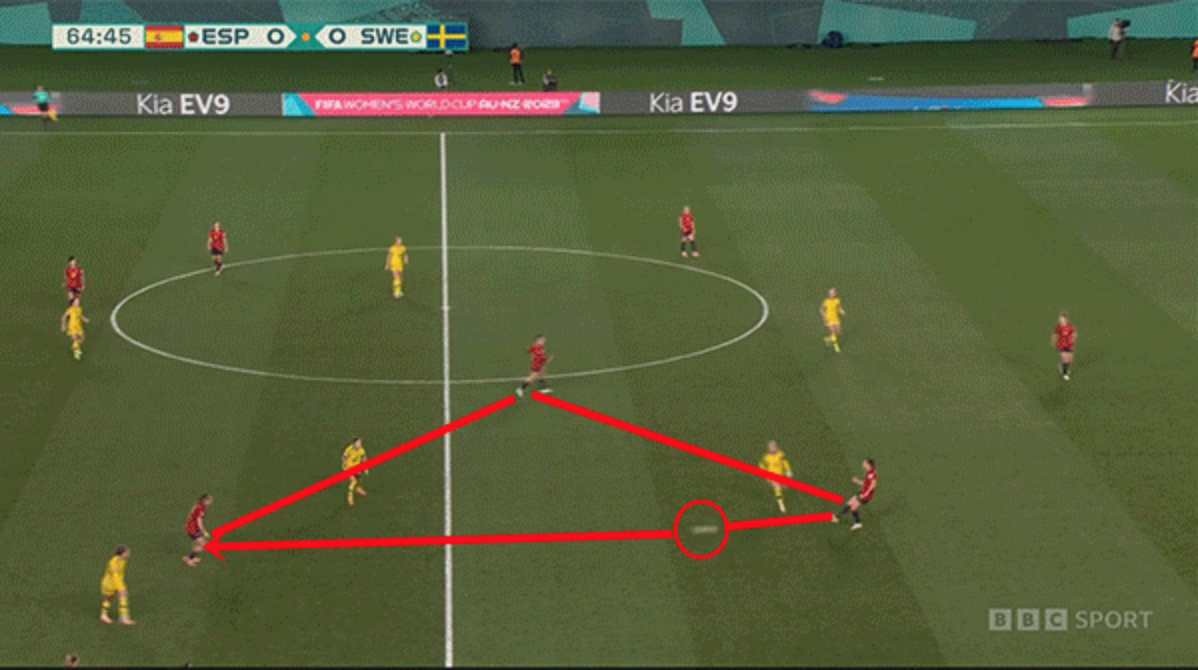

The glaring difference between the Italians and the Swedes was Italy’s ability to neutralize Spain’s threats. Sweden, in contrast, would not do the same. Though the Swedes remained quite disciplined in their compact shape, La Roja would find chinks in their armor. One of the ways that they did so was to pass in triangular patterns. This would not only allow them to build up play but also play out of pressure.

(Spain’s triangle passing)

Spain also employed asymmetrical patterns at times, particularly when building out the back, to avoid the Swedish press.

(Spain in an asymmetrical back four)

The most integral part of Spain’s back four was the play of their fullbacks. One cannot overlook the way Ona Batlle and Olga Carmona contributed to this system as their brilliant interplay and interchange created much confusion among the opposition defenders.

Batlle, in particular, stood out for La Roja in her position as a fullback as she played in both the right and left of their defense and her ability to read plays, smart movement, and technical ability were absolutely key to her team’s title run. Batlle and Carmona would work in tandem to not only snuff out attacks, but pull defenders out of position and then isolate them into 1v1 battles.

The game-winning goal, however, came from a set-piece. Teresa Abelleira’s short corner kick found a well-placed Carmona, who then fired on sight. The ball rippled the back of the net and with that, Spain found themselves in the final. It is a testament to this team’s versatility that they can find several different ways to beat their opponents.

The Final Game

Like the Dutch, Wiegman’s England employed a 3-4-1-2 formation that became a 3-5-2 at times. This was initially done to cope with Keira Walsh’s injury, as Katie Zelem stepped up to fill their role. The formation change would also complement England’s wide players, particularly Lauren James and Lucy Bronze. This new shape was first deployed against China and the Lionesses dismantled the team 6-1.

However, Walsh made a quick recovery and England decided to stick with the formation rather than switch back to a 4-3-3. While this would allow them to win games against Colombia and Australia, they would not get the same result in the final. Wiegman would not adjust her tactics until it was too late and it would prove to be fatal for the Lionesses.

Spain would also stick to the same system and deploy their 4-3-3. However, their system ended up dominating England. As was noted before, Spain used passing triangles to get their opponents to chase shadows. This would be an effective way to not only wear the opposition out but to evade their press as well.

They also timed their movements well in their quest to break down teams. Their defenders displayed exceptional awareness to snuff out England’s potential attacks. Spain’s defensive structure also let them anticipate the Lionesses’ actions as they knew where their pressure was going to come from when they won the ball. La Roja’s back four already read the next pass and knew where the next open space would be before the ball arrived.

While the system might seem complicated on principle, it really wasn’t. What made it seem that way was how the Spanish players executed these tactics, as they did so with a combination of deft off-the-ball movement, artistry, and grit. The defensive positioning of their players was one part of it, as was the use of attacking fullbacks and inverted wingers. The whole circulatory system would not, however, function without a beating heart pumping blood through the veins. And that beating heart was Spain’s midfield that dictated the movements around them, was their midfield, with the most powerful vessel being Aitana Bonmatí.

French artist Maurice Merleau-Ponty once said that the artist looks to the world in such a way as to allow it to move her body rather than to describe it (Parry, 2010). This quote most definitely applies to Bonmatí, who painted beautiful portraits across the canvas of the playing field. It seems like the midfielder was all over the place during this game, whether it was dropping deep to collect the ball, tracking back to defend, or camping in the half-spaces before making runs into the box for scoring opportunities.

Her passing range and ball carries were the result of an artist who used intelligence and determination to give herself the freedom needed to create a masterpiece. Bonmati’s ability to hold her position while she created chaos in England’s half is proof of this. The goal was to exploit the spaces in behind England’s wingbacks, and whenever they moved forward, Bonmatí would run into the vacant space left by a player to intercept the ball and launch an attack.

Oftentimes, her balls were sent to the players in the wide areas. Spain’s main attacking threat came through their fullbacks as both Carmona and Batlle would make runs towards the opposition’s defenders. Teams would try to respond to this by doubling down on them, but as they committed numbers to the defense, the midfield and wingers would then exploit the free space they left behind.

Spain would use passing triangles to not only move the ball around the pitch but to free up and then exploit the spaces around the opposition’s midfield and in the channels. This would then allow them to create 1v1 battles and at times, create overloads in these areas. This would allow either Carmona or Batlle to push the opposing fullback out wide or drive inside to affect play.

The two fullbacks used their interplay to deadly effect against England’s system, as the Lionesses couldn’t really get pressure on the fullbacks which was causing them problems. England finally made the necessary adjustments at halftime to mirror Spain’s 4-3-3. While they got the shape right, the personnel change was questionable.

Nigeria’s Women’s World Cup Dreams Once Again Come to an End in the Round of 16

One has to question why Wiegman did not bring on Chloe Kelly, who can deliver balls into the box, or why she took off Alessio Russo who is capable of making runs at the Spanish defense. Russo also possesses an aerial threat and could have exploited Spain’s weakness on setpieces. Then there was also the positioning of Lauren Hemp, where she could have played a wider role that would have allowed her to isolate fullbacks in 1V1 situations and get balls into the box.

England’s tactical setup let Spain’s wide players attack down the left and open up the game. This was also where Spain’s wide players truly shone, with the brightest jewel of them all being Salma Paralluelo. The player was omnipresent on the pitch and through both her darting runs and smart movement, she was able to find space behind England’s defense.

She also rattled England psychologically as rather than commit players forward to attack, they would leave a few behind, for fear that Paralluelo would blow past the stragglers left to deal with her. The fact that England’s Euros-Winning defense was under siege is a testament to what an incredibly brilliant player she is.

The one area where the player truly shined was through her off-the-ball movement. The best example of this was when Paralluelo chased Lucy Bronze into the midfield. Through her aggressive player-to-player marking, the winger pushed Bronze into a wall that consisted of four Spanish players. The Spaniards then took the ball off the fullback, then quickly moved it upfield, where it ultimately led to Olga Carmona’s game-winning goal.

It was a combination of these methods that allowed Spain to win the final. And in the end, they would be the most worthy winners of them all. This victory has been the culmination of several years of hard work and winning the trophy would be a revolutionary act in more ways than one.

The Legacy Afterward

Though Spain played and won the World Cup in a beautiful manner, their celebrations were unfortunately marred by ugliness afterward. During the post-game awards ceremony, the RFEF’s president, Luis Rubiales, forced a kiss upon midfielder Jenni Hermoso. Instead of being allowed to freely celebrate what was one of the happiest moments of her life, Hermoso was, instead, assaulted on international television for all the world to see.

The incident was the match that set off a tinderbox that set off an epochal explosion. And in the aftermath, previously dormant creatures rose from the ashes, and it came in the form of the abuse that the Spanish Women have endured for years, under both Jorge Vilda and his predecessor, Ignacio Quereda. The Spanish players have had to endure every form of abuse imaginable just to play the game and now it’s finally been laid bare for the world to see.

The one, silver lining in this tumultuous cloud is that something will finally be done to remove Rubiales and Vilda from power. However, it shouldn’t have taken this long for this to happen though, as the abuse has been occurring for several years. Nor should it have taken Spain winning a World Cup for this to finally happen. No one should have to play in an environment of fear and exploitation and sadly, the Spanish Women have had to operate in these circumstances just to play the beautiful game.

What’s equally as depressing is knowing that the Spanish Players aren’t the only ones to have suffered abuse while playing for their country. Other countries, such as Zambia, Haiti, France and many others, have also had players that were abused by staff while their federations did nothing about it. With this in mind, one can only hope that the Spanish players’ protest against their federation will lead to similar movements to root out the rotten elements around the globe.

From Show Games to Ballon d’Or: The Progress of Women’s Football in Norway

It is also worth noting that as good as this World Cup-winning squad was, they could have been even better. Players like Mapi León, Patri Guijarro, Nerea Eizagirre, Amaiur Sarriegi, Claudia Pina, Ainhoa Moraza, and Lola Gallardo, are all talented individuals who would have made important contributions to their national team. One could even argue that Mapi is the best centre-back in the world.

They were a part of the original ‘Las 15’ who protested against Vilda and his abuse, and absolutely refused to play for him. Had they not protested their coach, then this current Spain side would have been an even better team. They could have been borderline invincible (4-0 losses to counterattacking teams aside).

There are unfortunately a lot of what-ifs surrounding this Spanish team. Add to this the fact that the RFEF has constantly gaslit the players, fabricated statements for them, and threatened retaliation, and the situation seems quite harrowing. At times, it feels downright hopeless. However, these battles aren’t anything new to the Spanish Women. After all, they waged a battle to remove Quereda in 2015. They won that fight, and even a few players had to pay a heavy price for it, as they were never called to the national team again.

They’ll have to take up arms and wage yet another battle. Only this time, the spotlight is on them and they have both global support and many powerful people aiding them in their cause. The hope is that the Spanish players will win this war and have an inclusive environment where all of their best players can play for them. And that would make a really great team truly one of the greatest of all time.

By: Stephanie Insixiengmay / @statsandedits

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / Getty Images