Individual and Systematic in-Possession Considerations When Recruiting a Goalkeeper

In recent years, as football moves to more possession-orientated philosophies and approaches to the game, goalkeepers’ roles go far beyond just shot-stopping. In the ‘modern’ game, goalkeepers have to be adequate with their feet in possession, often used in the build-up and they have to ‘sweep’ more often, coming further off their lines as teams playing higher up the pitch.

I will be focusing solely on the first evolution, detailing some of the individual and systematic considerations required when assessing a goalkeepers’ in-possession abilities, which should be key recruitment considerations when assessing the transferability of a goalkeeper’s skillset to the team.

The player I will be using to demonstrate these considerations, and why they are important, is Burnley and England goalkeeper Nick Pope, who has been a discussion point for pundits regarding his distribution capabilities previously and has been fleetingly linked to Tottenham and Manchester United in 2021.

Nick Pope’s Passing Profile

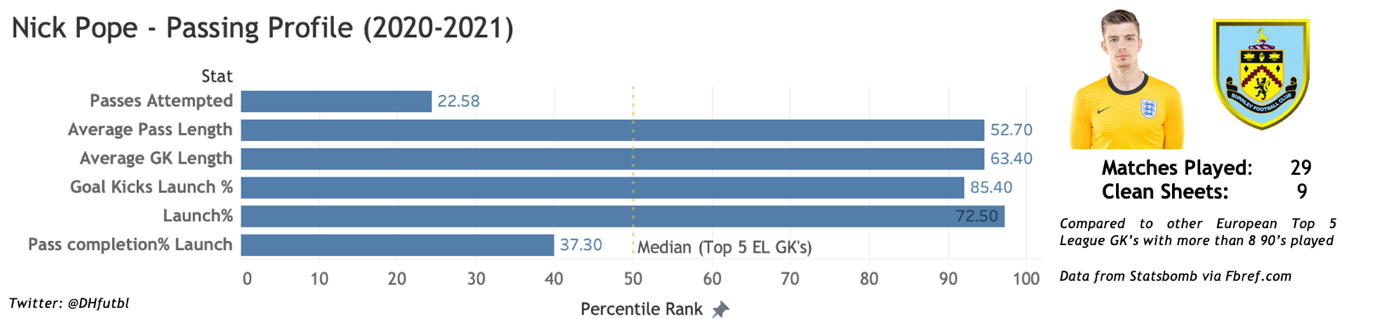

With respect to his kicking game, Pope can be seen as more of a traditionalist. The former Charlton keeper prefers to kick longer and play a limited role in the build-up. As evidenced by the below passing profile graphic, the Burnley GK situates above the 90th percentile for pass length, goal kick length and percentage launches, all indicating he kicks further, and more frequently than most European top five league goalkeepers.

NB: The data in the above chart was collated before the last three PL games Nick Pope played in.

Therefore, it is fair to say as guided by the data, Pope’s kicking game is low risk in nature and revolves around kicking long. His skillset to be able to complete this is sound, although by its very nature, is very limited in terms of variation. A majority of kicks are kicked with height as opposed to being drilled into their target, as this creates a situation for an aerial duel, which favours the physical profile of Burnley’s forwards.

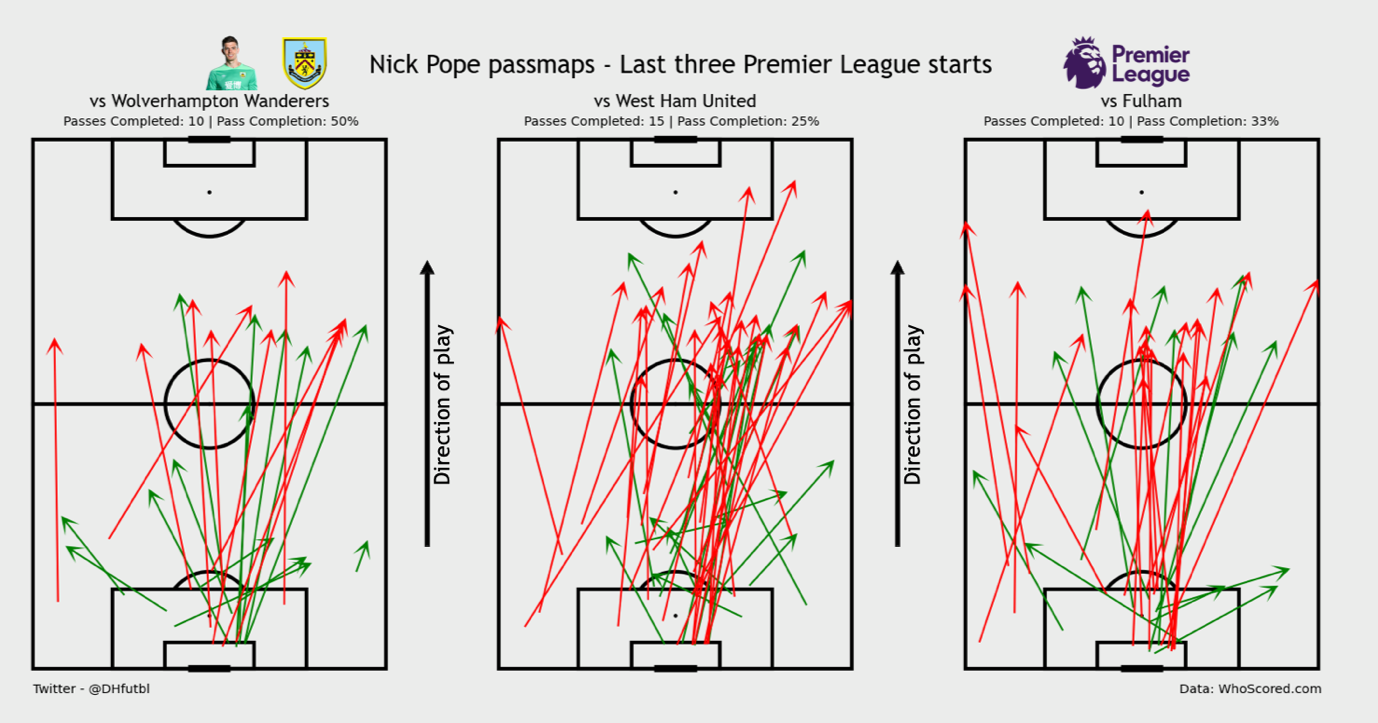

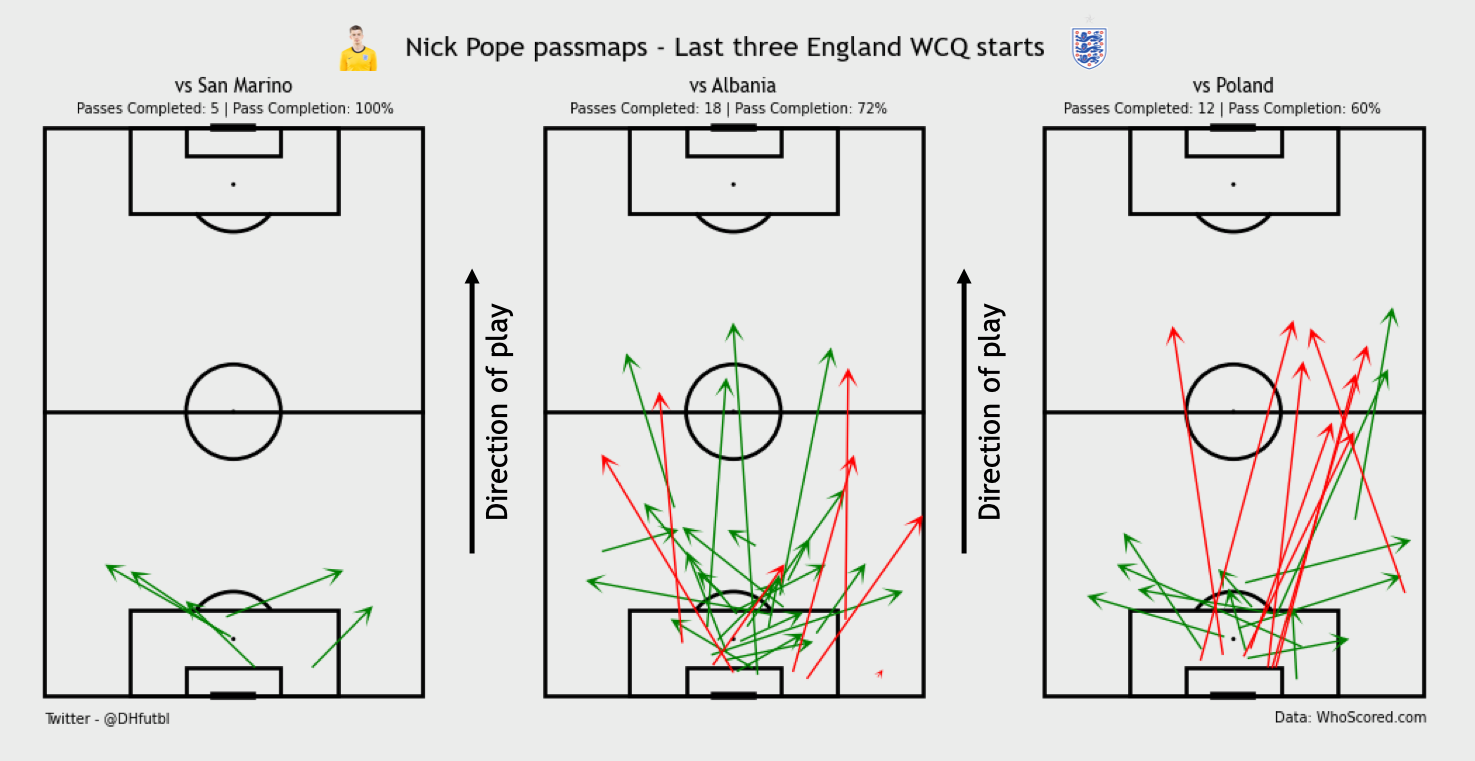

Visualising this matter further, below are pass maps from Pope’s last three league starts, highlighting in-game examples as to how this passing profile manifests in Pope’s aggregated actions on the pitch. The aggregated event data clearly reinforces the low-risk, direct approach that Pope’s data points towards.

Whilst his current role is fairly limited, as a scout looking to identify whether Pope is capable of transitioning into a more possession-based system, there is a wide range of skills you can look into in more detail to understand the potential for scalability.

From a technical point of view, one of these important skills is his first touch, as this forms the basis of any further actions. Often, when passed to in open play, Pope’s first touch is inconsistent. The subsequent knock-on impacts include the invitation of pressure from the opposition as more touches are required and the slowing down of any build-up play in the first phase.

Furthermore, body orientation upon receipt is another key skill for a goalkeeper who is looking to excel in a possession-based team. To be able to contribute effectively, his positioning when receiving the ball will require him to be open and manipulate the space in front of him to open up passing angles and options. Pope does struggle to do this, closing himself off from passing options through his body positioning.

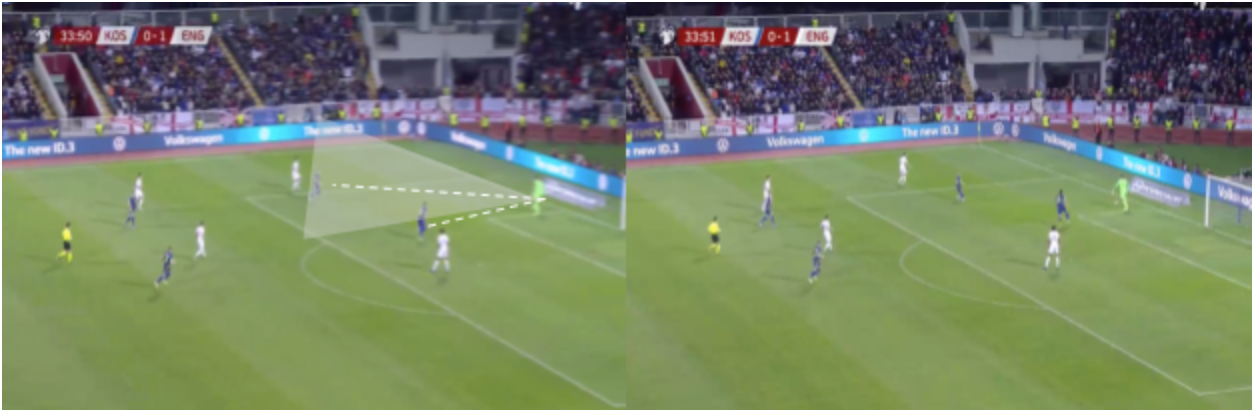

Both of these skills, and assessments of these skills, can be demonstrated by the two images from a pass back against Kosovo for England in 2019. The first touch is trapped underneath him, not allowing him to then pass with his second touch, thus requiring a further touch to clear his feet. By this point, Kosovo’s attackers are better positioned to press, forcing Pope to kick longer.

Relating to his positioning, upon receipt, Pope’s orientation is facing the touchline as demonstrated by the highlighted area, closing his back to a majority of the pitch and only presenting the small area directly in front of him as his effective line of sight when passing, limiting his ability to play out.

Aesthetically, he isn’t the most pleasing in possession, generally looking uncomfortable and in terms of preferences, Pope prefers to throw or roll the ball if he is playing shorter from open play. This tendency and the general aesthetics principle demonstrates the level of comfort of Pope in possession, as he opts to use these methods to distribute play short.

This likely reflects a lower level of composure, a key psychological trait for a goalkeeper when considering whether they are able to carry out a possession-based role for a team. Composure is important as they need to be able to receive under pressure, and subsequently be able to make clear decisions and for their technical skills to not be impacted.

From a technical and psychological point of view, his short-game is fairly limited by his overall ability and general discomfort on the ball. Other considerations include his tactical acumen to carry out a role in a more possession-based team, which includes understand movement triggers and making correct movements to be made to create overloads at times.

The level of Pope’s tactical understanding to undertake this role is likely open to question given a large portion of his professional career has been spent at a Burnley team who do not operate with these structures as discussed later, meaning this skillset will not have been refined.

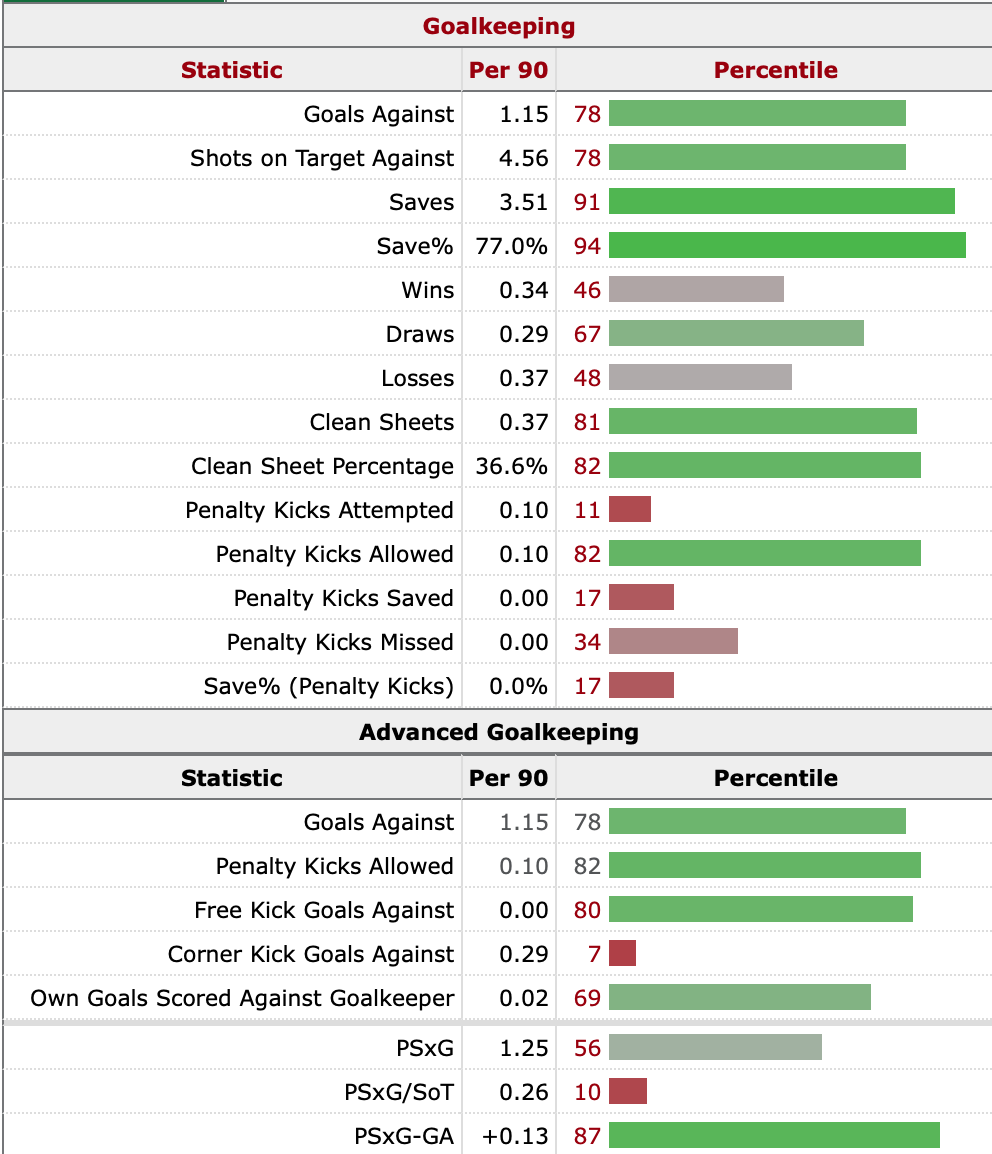

Taking into account wider considerations of Pope’s game, e.g. his shot-stopping performance, the data points to a very good goalkeeper when compared to his European top five league peers, which is generally backed up by a largely sound technical goalkeeping base, as can be seen by the below FBref percentile data.

For instance, in the now widely used PsxG-GA p90 figure, Pope ranks in the 87th percentile, demonstrating a well above average shot-stopping capability. PsxG – GA measures expected goals based on how likely a goalkeeper is to save a shot based minus goals allowed, with positive numbers suggesting an above-average ability to save shots per FBref.

However, with regards to the Soham-born keepers passing data points, the available data begins to paint a picture of Pope’s possession role in this Burnley team and his passing profile, which is then reinforced by an assessment of certain key technical skills.

More broadly, the high-level data with an individual focus does not consider certain systematic factors which impact the data, which present key considerations for recruitment teams when assessing individual players, and their suitability for certain roles. Therefore, further supporting analysis needs to be undertaken of Burnley’s overall build-up preferences and Pope’s role within that system.

How Does Burnley’s System Help Nick Pope in Possession?

Burnley’s preferences in build-up are a big determinant of Pope’s aforementioned passing profile, and also considers the potential limitations Pope has on the ball. Dyche’s team effectively skip phases of play in deeper areas of the pitch, bypassing the midfield and looking to hit the forwards early.

This approach is reflected in the teams progressive passing received metrics, which are dominated by the four forwards (Wood, Vydra, Barnes and Rodriguez), who range between five and nine progressive passes received per game, compared to their midfielders, who range from just under one to three progressive passes received per match.

From a tactical point of view, the direct approach employed allows Burnley to gain territory in the opposition half through winning the first ball or recovering the second ball and brings the physical attributes of their strikers into play as focal points. This plays to their strengths and can be viewed as a lower risk approach to football altogether.

For the goalkeeper in this system, the in-possession role is simple and predicated on going long to the two strikers. In open play, when Pope receives the ball, there is no structure to indicate any attempts to play through the phases. A primary indicator of an intention to play through the phases is the positioning of the centre backs when the keeper is in possession.

In the below scenario against Southampton, as Pope receives the ball neither Mee or Tarkowski are viable passing options in the cover shadows of the opposing forwards, and make no attempt to position themselves to receive, which in this scenario, would likely be to split and move towards each corner of the penalty box. The minimal effort to do so, and the above lack of any semblance of a possession structure in the first phase, confirms Burnley’s intention to take a more direct approach.

The evident lack of possession structures in the first phase is not an isolated incident. Repeatedly, Pope will have the ball, and by design, the entirety of Burnley’s defence will be very passive under the knowledge that Pope will be playing long, and rarely offer passing options.

Another example, this time against Wolves, with Pope recieving the ball in open play in the first image. Taylor at LB is not facing the play and is closely guarded by Traore, with Mee happy to occupy a similar space, and Tarkowski and Lowton also relatively closely marked. This once again leaves Pope no shorter passing options.

The second image demonstrates the point of release by Pope, with none of the players making any meaningful movements to offer for the ball, with Tarkowski actively moving into the opposing forwards cover shadow. The further lack of movement or intent to play short that precedes Pope going long only demonstrates further the favoured approach for Burnley and ignorance to any shorter build-up.

For teams that favour a more possession-oriented approach, they will often have very clear patterns and structures in this phase to progress the ball. However, Burnley do not require to have these structures in play as they are not looking to achieve progression in this way, falling back to their direct approach where Pope’s low-risk role in possession is to hit the forwards or wingers quickly to gain territory.

This structureless approach in the first phase does reflect directly on Pope’s data, as his lack of options in the build-up phase leading to him playing over the defensive and middle thirds of the pitch is demonstrated by the metrics which show passing length and launch%’s to be significantly higher than his peers. However, on the other hand, this approach also allows Burnley to play to his strengths and do not expose his in-possession deficiencies, meaning it becomes a self-reinforcing aspect to Pope’s individual profile as a player.

Considering the above, given Pope’s recent international involvement, we can see with England in the recent international qualifiers where Pope started, an idea as to the scalability of Pope’s on-the-ball abilities into a more possession-based system than the one used by his club side.

Unfortunately, a majority of the information that can be gleaned from these games is directly impacted by the lower quality nature of the opposition, which directly impacts their approach to the game e.g. tendencies to drop off and not pressure the goalkeeper and the game being played in the opposition half.

At a high level, in these games, Pope showed a degree of proficiency in playing out from the back, with a number of passes completed shorter when compared to the Burnley pass maps earlier in the article. However, against Poland, a more difficult opponent, where he had more of the ball and was required to be a more active participant in possession, he opted to go longer at times both in open play and goal kicks, likely due to the increased pressure and the better drilled nature of their opponent.

This basic visualisation, when coupled with the previous breakdown in his passing profile, displays that translating his skillset to a possession-based outfit will require a significant amount of work for a player whose low-risk passing profile is likely engrained at 29, with the previously mentioned technical and psychological limitations in his game likely to prevent him from excelling in a possession-based system.

Conclusion

Presently, Pope plays within a team that places little emphasis on playing out from the back and through the lines, which is where goalkeepers are expected to play a significant role in the first phase. This system helps Pope as it can play to his own kicking strengths, focusing on playing more direct into Burnley’s physical strikers.

When considering whether he can carry out a heavier load in the early build-up phases, as a possession-based team would expect, it is clear that certain technical and psychological limitations are built into his game, which would be difficult to overcome if a more possession-based team, such as Manchester United and Tottenham who he has been linked with, were to purchase him.

As such, it is now increasingly more important given how the game has evolved to consider these stylistic and technical factors, which are not exhaustively listed in this article, when recruiting a goalkeeper. This case study does demonstrate a number of the technical and other important aspects of a goalkeeper’s in-possession skillset, such as first touch, composure and broader tactical understanding, which are all key considerations when you are a possession-based team looking to recruit a goalkeeper.

It is important to note these limitations do not make a bad goalkeeper, only one that is suited to playing a different style of football, as Nick Pope has consistently proven himself to be one of the soundest, most reliable goalkeepers in the Premier League, just one that prefers to be more direct with his kicking.

By: @DHFutbl

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / Visionhaus – Getty Images