Tactical Analysis: Leandro Paredes vs. RB Leipzig

Going into Paris Saint-Germain’s first Champions League semi-final in 25 years, Thomas Tuchel made four alterations to the side that beat Atalanta 2-1 in the quarterfinals. However, only one of those changes can be considered tactical, with Kylian Mbappé and Ángel Di María taking their regular place in the front three beside Neymar, after returning from injury and suspension respectively, while Sergio Rico deputized for the injured Keylor Navas.

Interestingly, Leandro Paredes replaced Idrissa Gana Gueye in midfield for Paris Saint-Germain and will be a subject of this analysis as he played a crucial role in achieving the dominance that helped produce the comprehensive 3-0 win. The Senegalese started in midfield against Atalanta, but he was subbed off in the 72nd minute for Paredes; PSG would go on to score two late goals and advance to the final four.

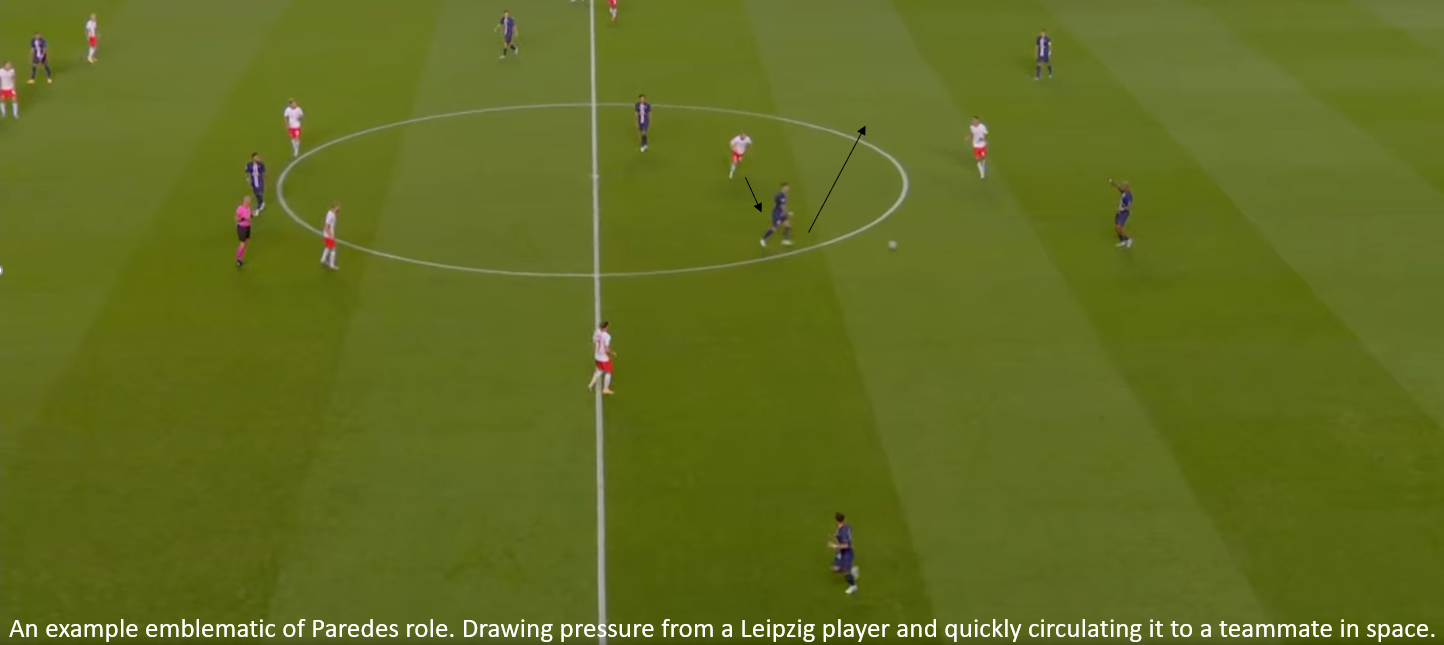

It was noticeable how frequently PSG sought to move the ball to Paredes, with Ander Herrera comparatively seeing very little of the ball, particularly during the build-up phase. With Verratti nursing an injury, Paredes was the nucleus of the midfield, the player who could reliably receive high volumes of possession and make the correct decision. His primary responsibility was to draw pressure and relieve a teammate of pressure elsewhere through quickly circulating possession.

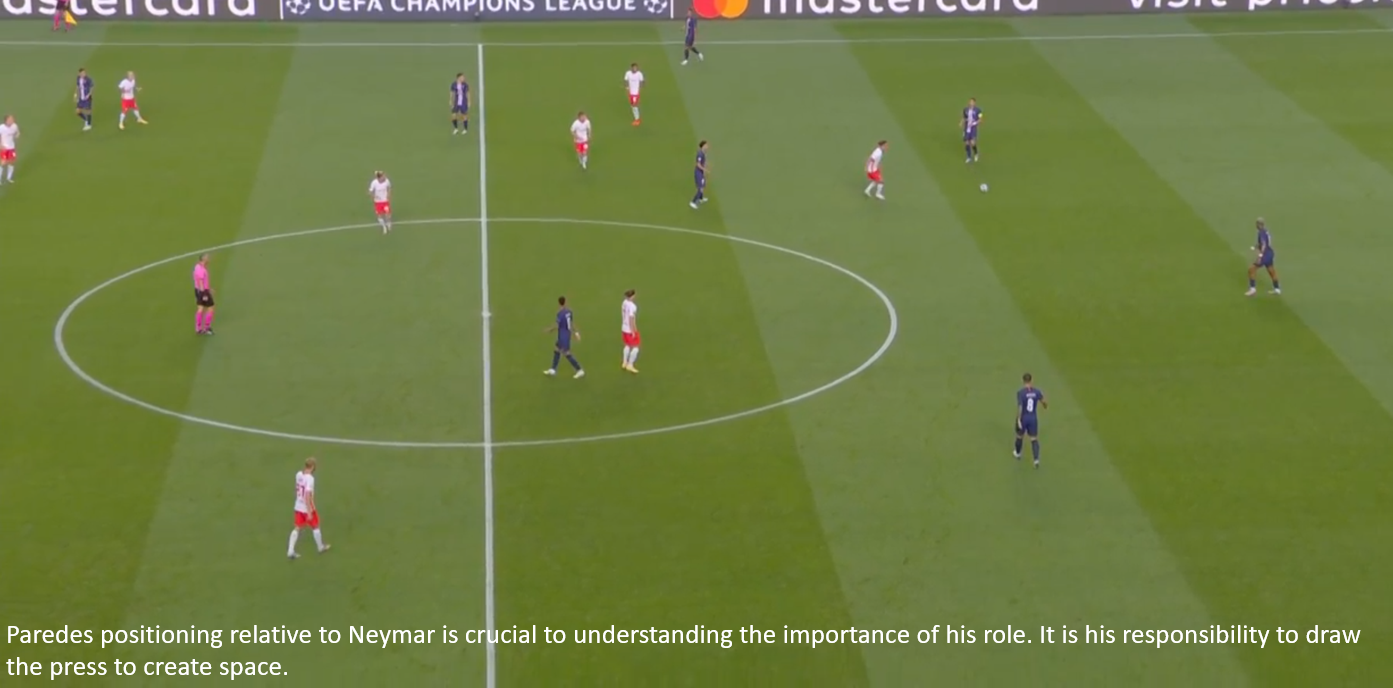

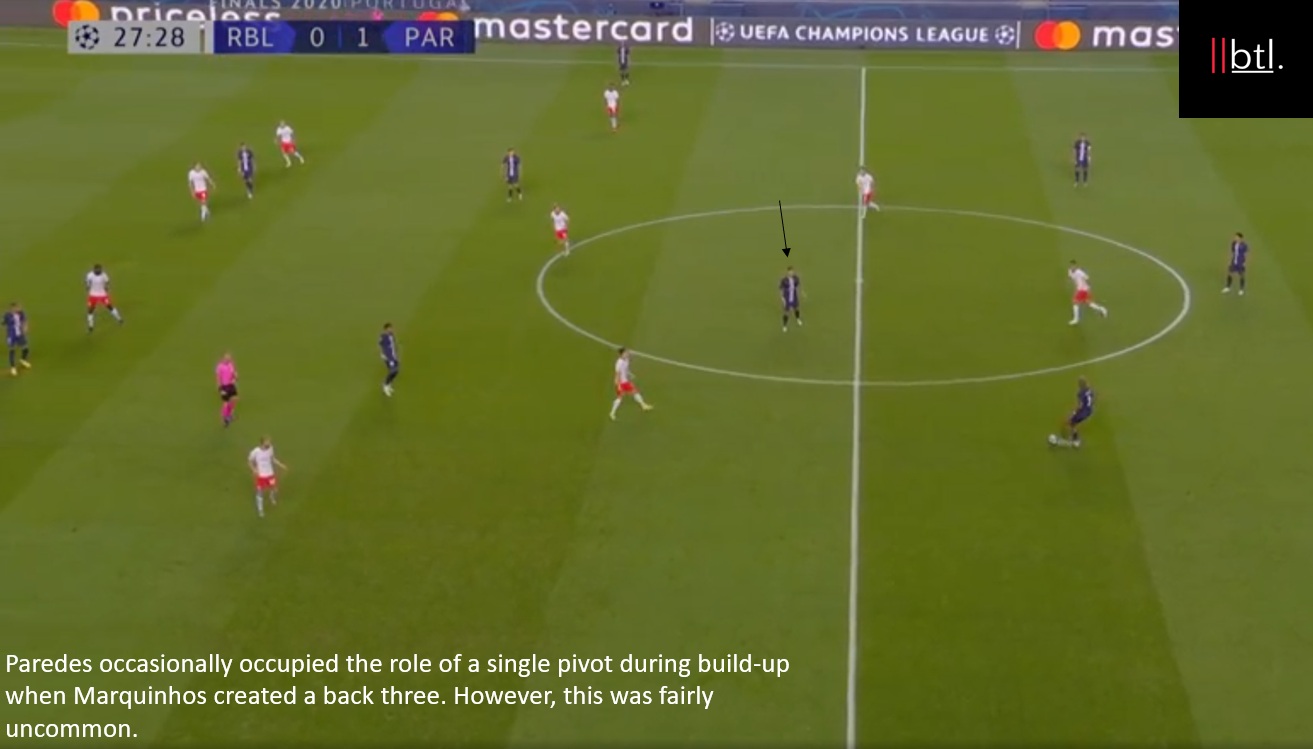

During periods of sustained possession, Paredes would drop deeper to form a double pivot with Marquinhos. He would predominantly occupy the left half-space, creating asymmetry, as Marquinhos would retain his central positioning, drawing lone centre forward Yussuf Poulsen onto him.

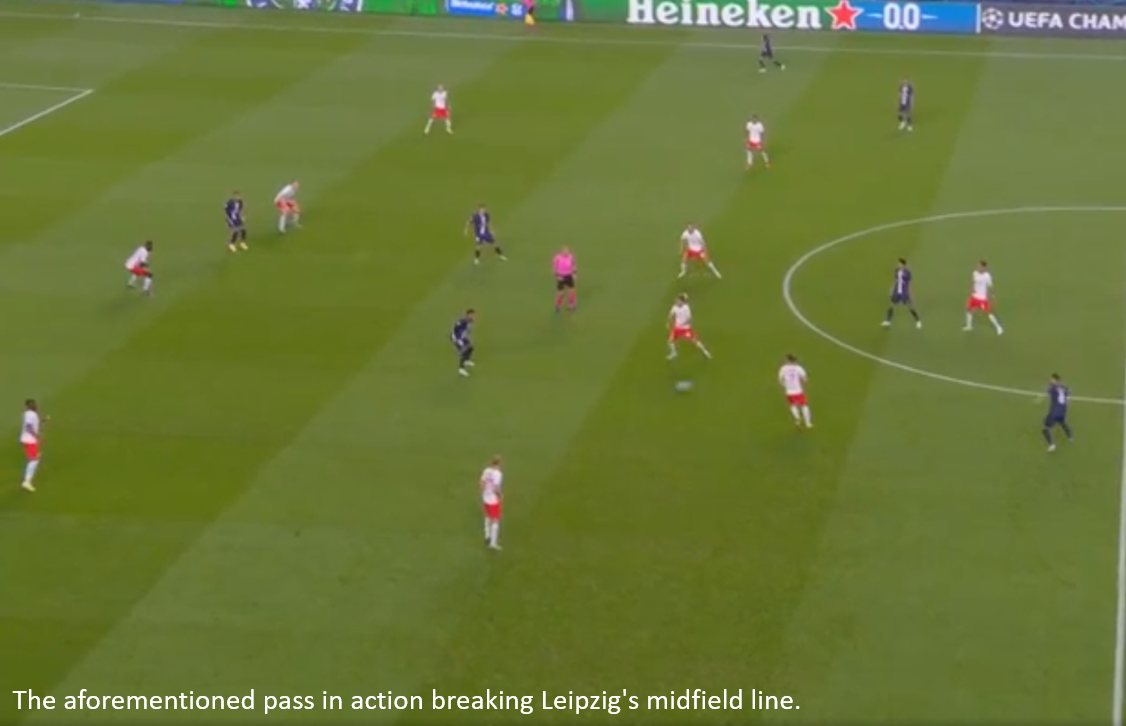

The shape created resembled a parallelogram and facilitated safe circulation of possession, as pressing Paredes in his deeper position forced Leipzig to break their 4-5-1 defensive shape, potentially exposing space in between the lines. Moreover, even if Leipzig decided to press the Argentine, it would often be fruitless as Parades always had a passing option open due to PSG’s numerical superiority in midfield.

Paredes receiving possession served as a pressing trigger for Leipzig as they sought to make it difficult for him to turn and play a progressive pass in between the lines. This consequently led to Paredes recording a high pass volume (72/77 passes completed) as PSG’s sought to maintain high levels of possession and eliminate risks stemming from high turnovers.

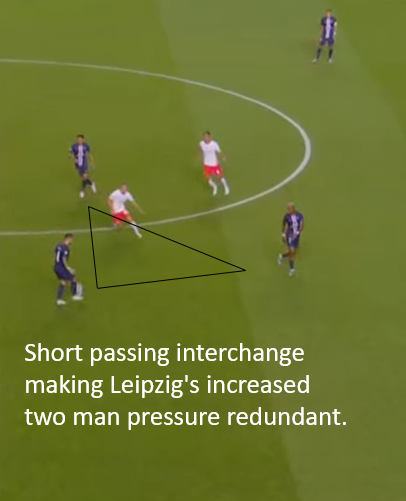

This resulted in possession being circulated between Paredes and the surrounding players in the box. The player often responsible for the pressing action was Marcel Sabitzer, as his positioning most closely corresponded with Paredes.

This created issues for Leipzig as Paredes is proficient at playing quick simple passes, meaning he could return the ball before Leipzig could engage, resulting in whomever received possession from Paredes having a better opportunity to find Neymar in between the lines, as Sabitzer was responsible for marking the zone Neymar would most frequently occupy.

As such, Paredes played a crucial role in disrupting Leipzig’s defensive shape through being a trustworthy figure to safely bait the press, inviting the opponent forward as to create space for teammates elsewhere.

Paredes was paramount to PSG’s patient approach in possession which sought to slowly progress and create space for crucial actors while maintaining protection from turnovers through playing safely and ensuring numerical advantage against the first wave of pressure.

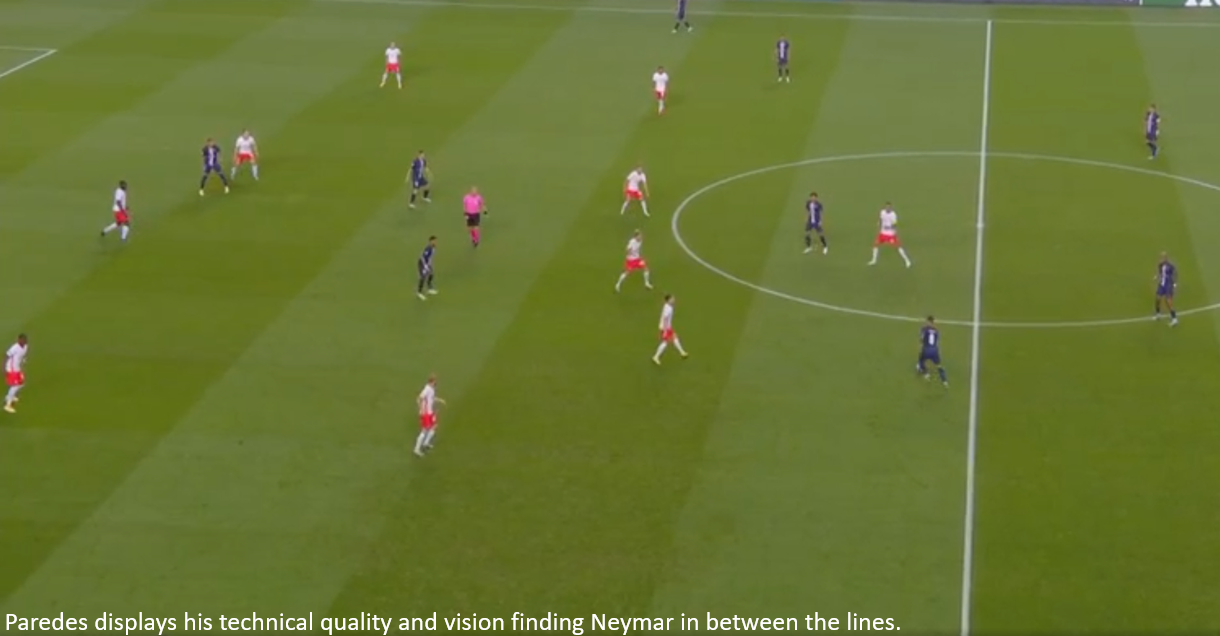

His prerogative was to recycle possession, allowing PSG to gradually gain territory. However, he did attempt riskier passes when the opportunity presented itself, as shown below, where he received less pressure than usual.

Not only was Paredes able to break down Leipzig’s compact midfield with laser-guided passing, but he also had the ability to combine with his teammates and progress play into dangerous positions, allowing PSG to open up and exploit space. RB Leipzig viewed him as too dangerous to be allowed time and space in possession and consequently had to apply pressure.

Irrespective of the approach taken by Leipzig within the microcosm of handling Paredes, space could be exploited in between the lines (vertical) or through a difficult pass between the lines (horizontal) if they did not press him, or through quick circular passing and disrupting the defensive shape if they decided to press. Paredes acted as PSG’s primary progressive player either through inviting the pressure or playing the decisive pass to break the second line when free.

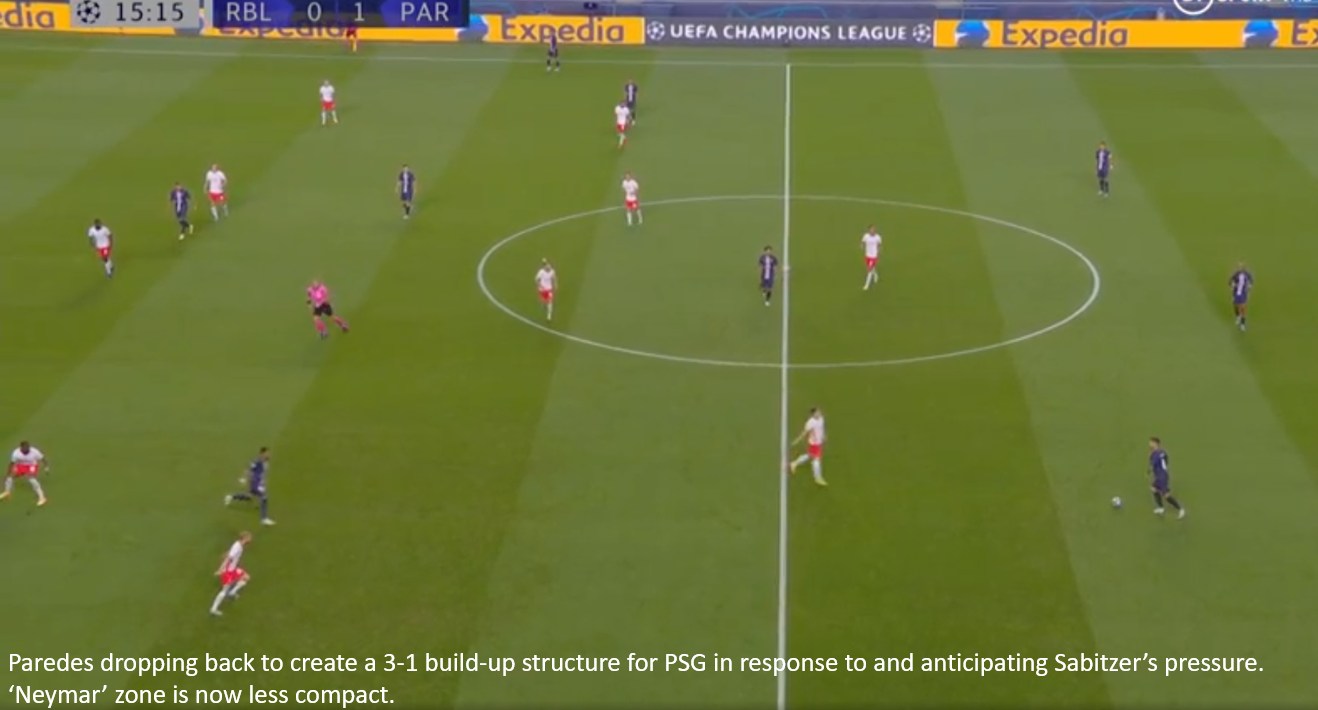

When facing greater pressure from Leipzig, one of Marquinhos or Paredes (dependent on the positioning of the ball) would drop in to create a back three, luring Leipzig further forward as to expose space.

This proclivity was more noticeable with Paredes in periods of uncontrolled possession, as he was often the player drawing the pressure, reducing Leipzig’s horizontal compactness, and creating a void in the half-space for Neymar to move into.

This meant his role was adaptable based upon how Leipzig responded to PSG’s desire to hold deep central possession. Should Leipzig decide to press, Paredes could drop deeper to ensure numerical superiority against the front two. Should they sit off in the 4-5-1 structure, he could advance parallel to Marquinhos.

Occasionally, and most frequently when PSG were building from the back facing sustained pressure from Leipzig, Paredes would move centrally to create a 3-1 build-up shape as Marquinhos provided the numerical superiority PSG desired. He had to remain constantly aware of his surroundings and would adapt accordingly to ensure that PSG retained possession and could look to move forward.

In the example below, after receiving a pass from Presnel Kimpembe, he is able to safely progress possession into Neymar, as there is acres of space between Sabitzer and Kevin Kampl, with the Brazilian positioned perfectly for a quick pass.

As the game progressed, Leipzig increased the intensity of their pressing, with Poulsen gaining greater support, as a 4-4-2 shape was often formed with a midfielder stepping forward. With PSG leading, the Parisians were able to pass around in their own half, luring Leipzig in with stagnant defensive possession.

This deep possession acted as rest possession, a time-wasting mechanism and space creation tool if Leipzig were impetuous. Leipzig’s press failed to challenge PSG, as Paredes and the supporting cast reliably outnumbered Leipzig and had the technical proficiency work the ball in artificially created tight spaces to relieve pressure elsewhere.

Out of possession, Paredes also played a significant role by engaging in PSG’s narrow pressing efforts which sought to make it difficult for Leipzig to consolidate possession. By attempting to force play out wide, PSG could then close down Leipzig’s players in possession with a touchline press.

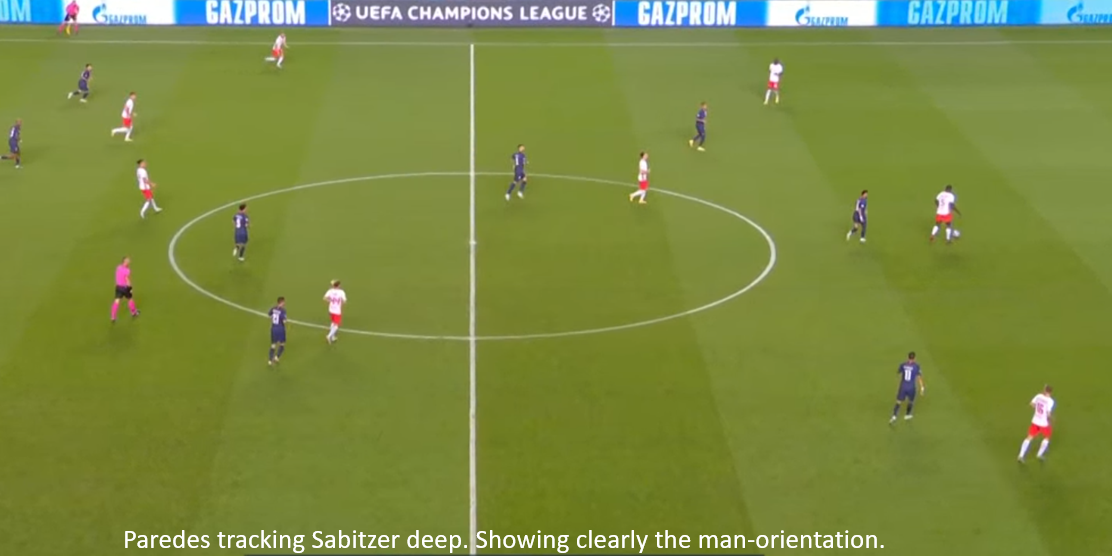

Paredes constantly tracked Sabitzer’s movements, preventing the Austrian from getting involved in the game and cutting off a central passing option for Leipzig.

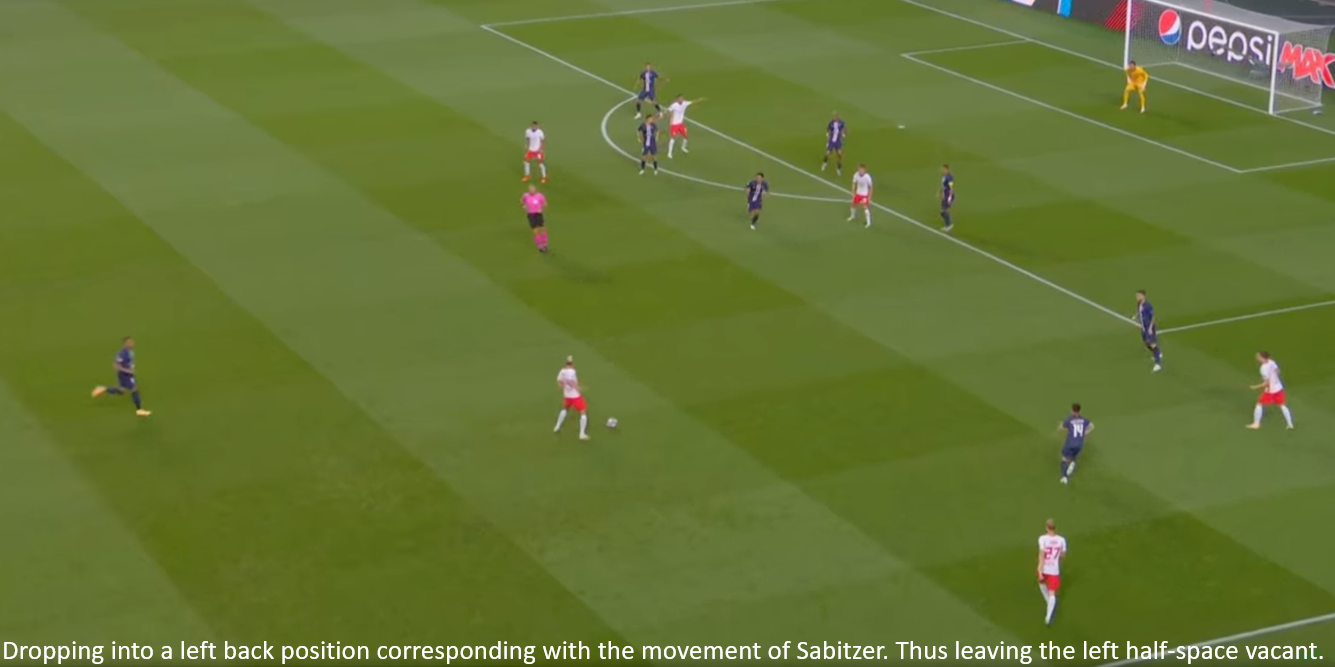

He therefore did not have a settled defensive position, but rather a position that was dictated by the movement of Sabitzer, meaning PSG’s defensive shape was not settled as it was dependent on where Sabitzer sought to collect possession.

His most noticeable involvement off the ball was for Di María’s goal, where he intercepted possession after following Sabitzer deep. His clever and accurate pass to Neymar allowed PSG to capitalise upon Leipzig’s lack of defensive structure following the turnover. A more traditional ‘ball winner’ such as Gueye or Herrera would have struggled to pull off a pass of requisite quality.

To summarise, Paredes moved where he could best receive possession and help PSG progress the ball, constantly attempting to open and exploit passing opportunities. He acted as a black hole in the positive sense by drawing PSG’s play and Leipzig’s players towards him.

The Argentine controlled the game through short passes while also being able to play between the lines or going direct. He was the epitome of the term “regista,” although he didn’t shirk his defensive duties either; he worked diligently out of possession to mark Sabitzer out of the game.

His outstanding performance justified Tuchel’s decision to include him in the line-up over Gueye as PSG’s possession game became much less reliant on Neymar during transitional phases in comparison to the Atalanta game where they lacked a controlling figure like Paredes.

By: @mezzala8

Featured: @GabFoligno