Tactical Analysis: Mikel Arteta’s 3-4-3

When Mikel Arteta joined Arsenal as manager, he knew his work was cut out for him. Stepping into a team with a paltry win percentage of 34.6% while conceding 1.5 goals per game, the former Manchester City assistant coach initially sought to make the Gunners harder to beat with a 4-2-3-1.

While this raised an already meagre win percentage to 50% and reduced the amount of goals conceded per game to 1.05, Arteta opted for a 3-4-3 in ten of his final 11 games in all competitions – winning 70% while conceding 0.7 goals per game and scoring 1.8.

In this system, Arteta put his former boss Pep Guardiola and Premier League champions Liverpool to the sword using the same group of players which were beaten comprehensively by the league’s top two sides earlier on in the season – a hallmark of a good coach.

Photo: Getty

By compartmentalising each role within Arteta’s 3-4-3, we can see if this system is sustainable for the Gunners in the long-term and what the club must do to add depth to what looks like an already promising system.

David Luiz in a Back Three

The main passage of play we saw from Arteta’s three-man system often revolved around having more numbers in the first phase with five defenders instead of four. The ball was mostly played wide to the wing backs who took advantage of width, stretched teams open and cut back inside to exploit the gaps.

Simply put, more numbers at the back meant more solidity for Arsenal’s defenders, particularly as David Luiz is noticeably better in a three with two other centre backs essentially anchoring him. While this paints over the cracks of his defensive deficiencies, it also accentuates his ball-playing abilities from a deep position.

The Brazilian’s defensive and passing stats before and after Arteta’s system change makes for interesting reading. In a four-man defence under Arteta, Luiz’s average progressive distance in passes was 332.86 yards per game last season but in the 3-4-3, he recorded an average progressive pass distance of 365 yards per game.

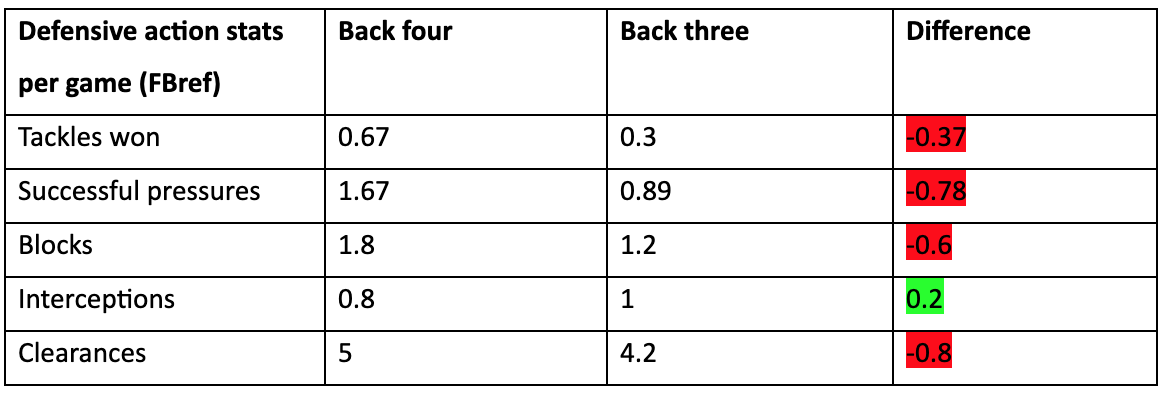

Defensively, Luiz is less involved in defensive actions in a back three compared to a back four, winning less tackles, making fewer blocks and clearances as well as instigating less successful pressures per game.

This makes sense given Luiz’s reputation as an aggressive error-prone defender. He cannot be left to do the majority of the defensive work and thus his defensive partners, Rob Holding and Shkodran Mustafi, weigh in with more blocks and clearances per 90 respectively.

Building Out from the Back

Arteta’s choice of centre backs in a back three is also very key in his approach to building up play. Other Premier League teams like Wolves which use three at the back do not always select traditional centre backs. Roman Saïss, Conor Coady and Leander Dendoncker are all recognised defensive midfielders but provide the technical assurance of a midfielder in Nuno Espírito Santo’s system.

These players add an extra level of technical quality a traditional centre back does not usually offer while also presenting an extra man in build-up who is more comfortable receiving the ball and moving it up the pitch.

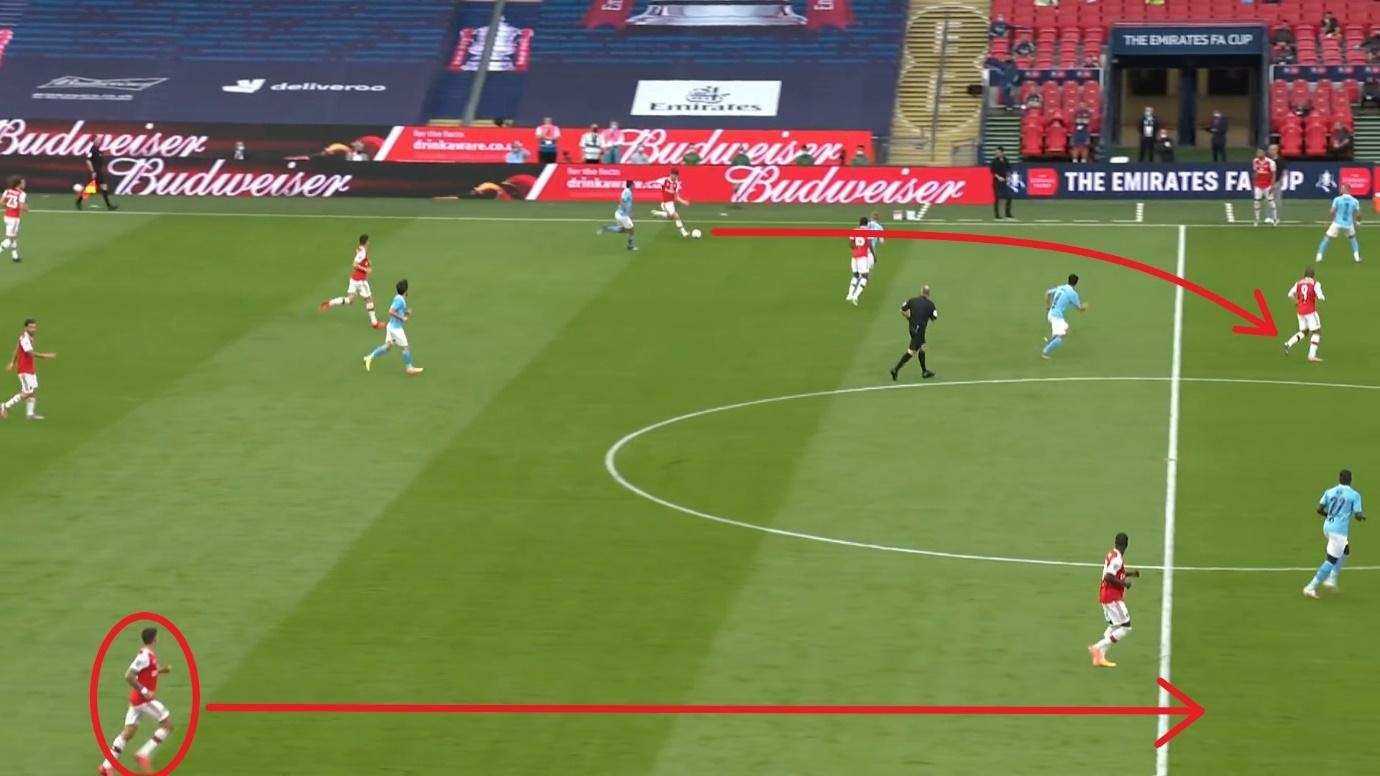

With Arsenal, Kieran Tierney is a left back by nature but slots very well on the left of Arsenal’s back three, sometimes pulling out wide as an auxiliary left back to overload the left channel alongside the left wing back and left forward.

The above picture is the ideal attacking scenario for Arteta’s Arsenal in a back three system. Even with all five of Chelsea’s defenders behind the ball, the Gunners are a man up as Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang can either play a reverse pass to Tierney or Ainsley Maitland-Niles to cut the ball back or pass inside to either Alexandre Lacazette or Nicolas Pépé.

With Tierney (circled) pushed up on the left with Maitland-Niles, Reece James and César Azpilicueta get caught in two minds over who to mark, allowing Aubameyang to pick the ball up in the left half space with a number of penetrative passing options to choose from.

Thus, Tierney’s involvement in this sequence tipped the superiority on the left in Arsenal’s favour. James and Azpilicueta always left a man open once the Scotsman joined the attack. Either Mason Mount or Jorginho (circled) should be covering the ex Celtic man to even up the numbers in this area.

Tierney’s width as a centre back also provides a way out when playing against sides with a back four. The opposition’s front three will normally seek to press Arsenal’s back three in the first phase but a central midfielder, normally Granit Xhaka, drops deep to cover. This leaves the 23-year-old free as a passing option with the wing back and left forward free to exploit space further up the pitch.

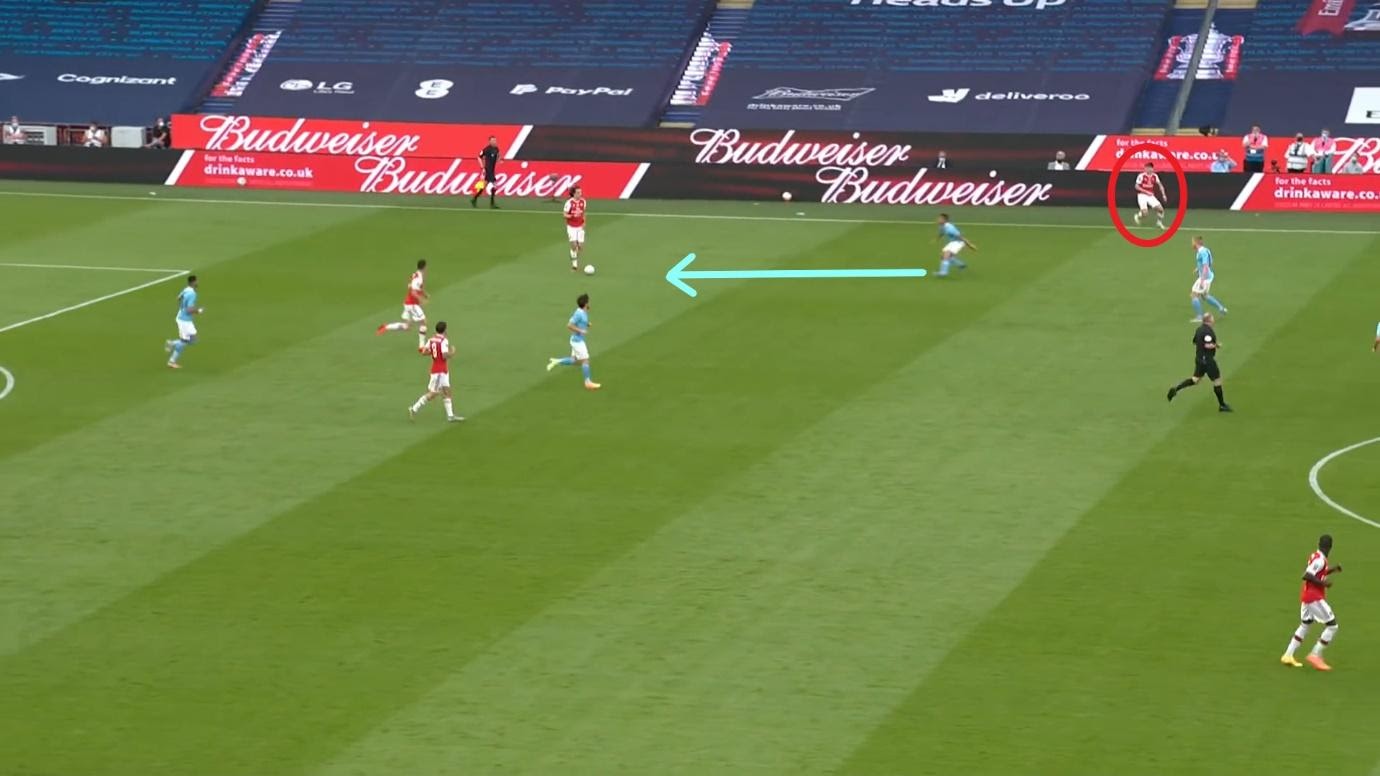

This was the situation in Arteta’s semi-final upset against Manchester City, where Gabriel Jesus, Riyad Mahrez and Raheem Sterling harried the back three in possession. As Jesus went to press Luiz, he opened up a passing lane to Tierney (circled) through City’s first line.

This matches Bukayo Saka’s initial assessment of Arteta’s philosophy – to pass only when you are pressured, thereby attracting your teammate’s marker towards you and making it easier to receive the ball.

After receiving, Tierney drives forward and delivers another line-breaking pass to Lacazette dropping deeper who turns and spreads the play to Héctor Bellerín (circled) on the opposite flank. This quick, penetrative passage of play resulted in Arsenal’s first goal of the game but it is a move they have used on more than one occasion.

Lack of Midfield Cover

However, the issue with Arteta’s 3-4-3 is that adding an extra defender means you take a player away from midfield and risk losing the battle in this area. This approach seemed to work best against teams with aggressive pressing strategies like Liverpool and Manchester City where Arsenal essentially ceded possession, defended as a back five and picked their moments to attack.

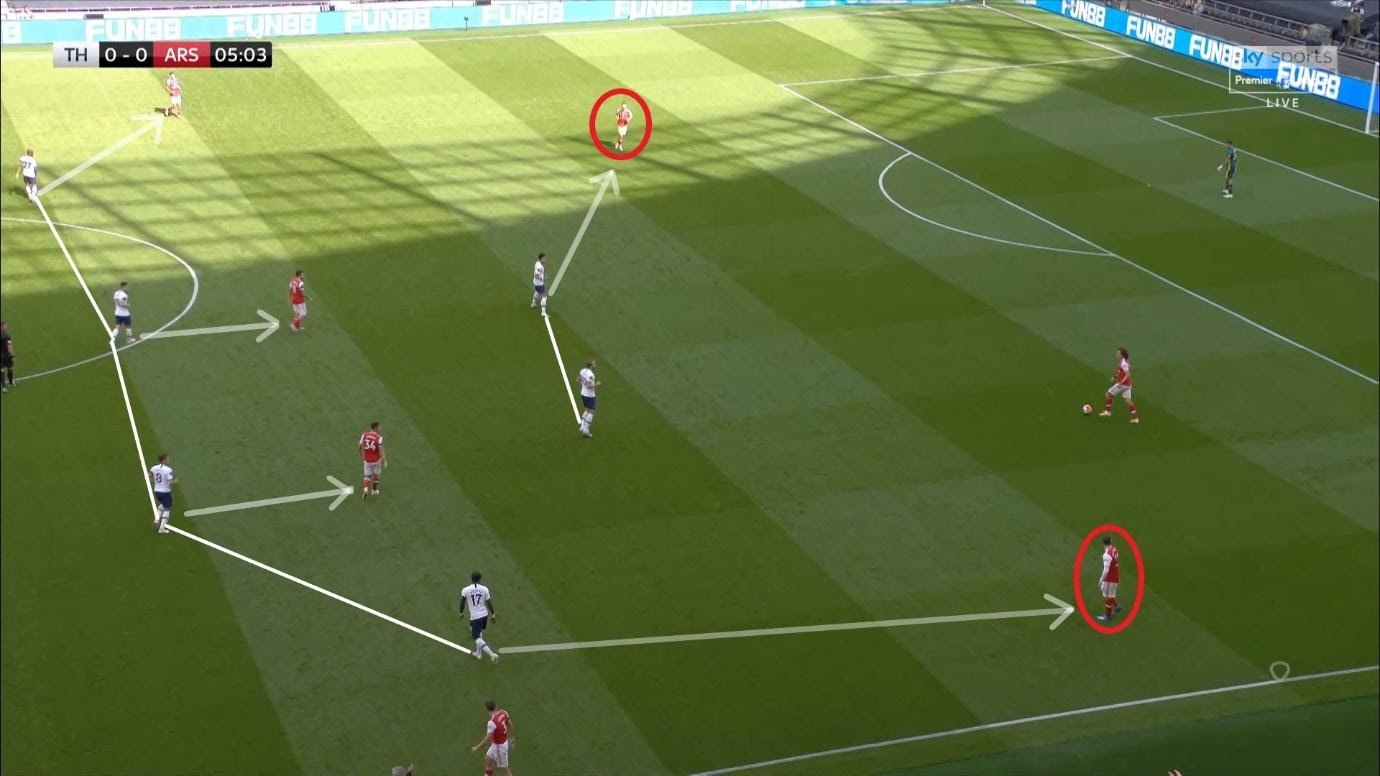

But when facing sides that gave them the ball and sat back, Arteta’s midfield in this three-man system failed to progress the ball nearly as well. In the most recent North London derby, José Mourinho lined up his Tottenham side in a compact 4-4-2 with Harry Kane and Heung-Min Son up front. Even with their numerical superiority in build-up, Arteta’s men found it difficult to impose themselves for large parts of the game.

As the above shows, Kane and Son blocked the passing lanes into Xhaka and Dani Ceballos, while a pass to either Sead Kolašinac or Mustafi (circled) ran the risk of triggering a Tottenham press which would have squeezed Arsenal’s defenders against the touchline in a dangerous area.

This volume of opposition players in the middle third stifled the team in a number of ways but the double pivot was most disrupted. As impressive as Ceballos and Xhaka can be on the ball, their creativity was thwarted as Mourinho instructed his players to form a box around the central midfielders.

If the ball found its way past Tottenham’s attackers to Xhaka or Ceballos, Harry Winks or Giovani Lo Celso pressed up against them before they could turn, forcing the ball back to Arsenal’s defenders. The Gunners often went long as a result but to little avail.

It is no coincidence that Arsenal performed worse in the games where they had their highest share of possession – their only two losses in this system coming against Tottenham (62%) and Aston Villa (68%). Without a creator in midfield, Arsenal lack the guile to open up compact mid and low blocks and Arteta’s 3-4-3 does not facilitate this kind of player given the extra defender.

While the argument could be made that Arsenal still have the channels to exploit, without the ability to progress play centrally this could render them slightly one-dimensional against teams who opt to drop back. To prevent Arsenal from overloading the wide areas, opponents could also line up with a back three and match them man for man to nullify their dominance.

Arteta’s Attacking Set-Up

The front three all acted as forwards which suited the likes of Aubameyang and Pépé as they are not traditional wingers, their danger comes from cutting inside onto their stronger foot to cross or shoot as opposed to beating their man to cross.

Photo: PA

Aubameyang was more dangerous when deployed on the left of either a four-man or three-man system. The Gabonese international scored 17 goals in 20 games from the left in all competitions last season – a rate of 0.85 goals per game. Meanwhile as the central striker, he only scored nine in 18 games – a rate of 0.5 goals per game.

In Arteta’s 3-4-3, this mark-up from the left is largely down to the combinations Aubameyang has at his disposal – with the left wing back, left centre back and left central midfielder. This range of passing options can be very difficult for most sides to deal with as it leaves defenders second guessing who to challenge a la Azpilicueta and James in the FA Cup final.

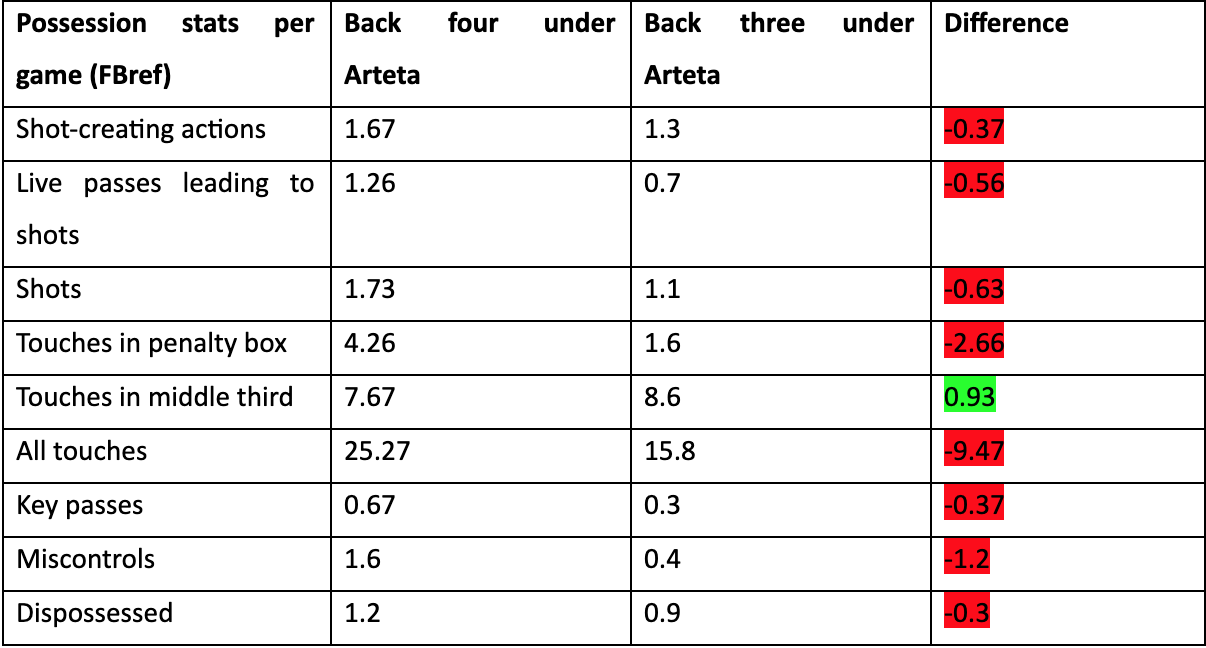

Lacazette dropped deep and used his hold-up play to bring others into the game, usually on the counter-attack. As Arsenal saw less of the ball in the 3-4-3, this meant Lacazette was less involved in Arsenal’s attacking play. According to FBref, Lacazette went from taking 25.27 touches per game in Arteta’s 4-2-3-1 to 15.8 in the Spaniard’s 3-4-3 in all competitions.

Such a dip in the Frenchman’s involvement negatively affected his possession stats in almost every department bar touches in the middle third when comparing his games in both of Arteta’s four-man and three-man systems. This was due to his false 9 tendencies in his more withdrawn role.

Arteta has proven so far his 3-4-3 can get the better of the top sides, winning three of his four matches against the top six with this system. By giving Luiz the necessary defensive cover in a three-man defence and the freedom to make penetrative passes, while overloading the wide areas and making the most of Aubameyang’s finishing, Arteta’s 3-4-3 does a brilliant job of making the team more clinical despite boasting less quality than his rivals.

However, whether this system works against more conservative teams who will give Arsenal the lion share of possession remains to be seen. If Arteta plans on using a three-man defence against such sides, perhaps the Spaniard could opt for a 3-5-2/3-4-1-2 with a natural playmaker (cough, cough Mesut Özil) operating between the lines. This would relieve Lacazette of having to drop deeper and allow the Frenchman to attack the space with Aubameyang, Pepe and co.

Regardless, Arteta’s impact in the short-term bodes well for his time with the Gunners. He will doubtless look to strengthen this summer but his squad appear to have reacted well to his tactics and coaching. After years of stagnation, the future looks at least mildly exciting for Arsenal fans.

By: Ahmed Shooble

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / Stuart McFarlane