Tactical Profiles – Inter’s Onslaught Under Conte

Inter Milan are – as everyone knows them – the team regularly touted to usurp the inevitable Italian champions Juventus, and ultimately suffer at the behest of their own incompetence.

Everything post-Mourinho has led to the same question asked over and over and over; why can’t Inter do it? Why do they keep failing? Well, an obvious suggestion is that there was always a key flaw to whatever side they built, and that when that flaw was exposed they would rely on a talisman to lead them out of trouble.

This season, though, all of that seems rather alien.

The man at the helm

There are suddenly adults in charge of the Nerazzuri, chief amongst them a former Serie A winner with the enemy: Antonio Conte.

Curiously, Conte was a pragmatist at Juventus. He only implemented the back three when he realised he had one of the greatest central defensive contingents of the decade – Bonucci, Chiellini and Barzagli – and realised he couldn’t possibly leave one of them out. From there, his philosophy of direct, aggressive football cultivated a record breaking one-hundred-point season, titles in multiple countries and a run to the semi-finals of the Euros.

Then, at Chelsea, he was strangely labelled a “defensive coach” due to the manner in which he won the title.

If there was ever a way to dispute that claim, it’s this season’s Inter.

The formation

Conte has, as expected, deployed a 3-5-2 system with similar facets to the innovative 3-4-2-1 he deployed at Chelsea. Now, however, instead of superstar wingers, he has a front pairing full of ingenuity in Romelu Lukaku and Lautaro Martinez alongside goalscoring midfielders in Stefano Sensi and Nicolo Barella.

However, just seeing Inter’s formation as a 3-5-2 would do it an incredible disservice, as it is so much more than that.

Attacare, Attacare!

It was Pippo Inzaghi – famed for his goalscoring exploits as a player – who suffered the indignity of having to shout the word “Attack!” in front of his players at a meeting called by his enigmatic club owner Silvio Berlusconi while at AC Milan. The scene became so bizarre that Berlusconi himself begun belting out the phrase “Attacare! Attacare!” as some kind of demand to both players and manager.

Should Berlusconi have watched his former cross-town rivals at all this season, he would presumably be salivating wildly.

The 3-5-2 formation is nominally very flexible – a good manager can manoeuvre his fullbacks to get beyond the midfield or have one midfielder be more attacking in a sort of triangle, or perhaps even have the fullbacks in a line with a deeper playmaker, then launch the two midfielders beyond.

Conte has taken that notion and exacerbated it to the extreme.

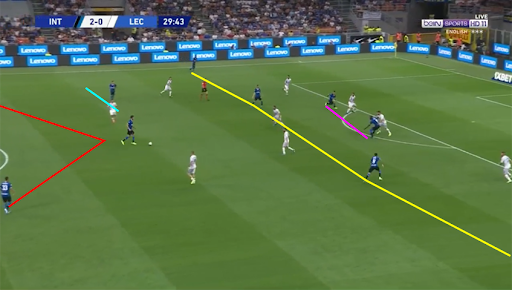

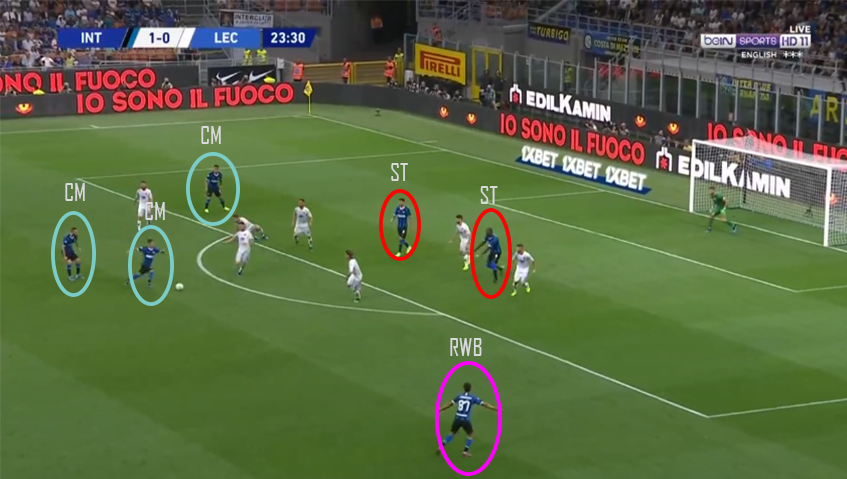

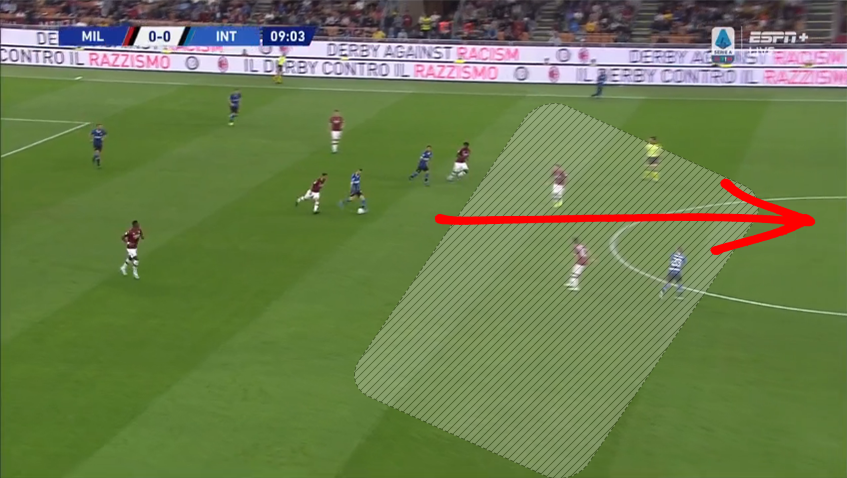

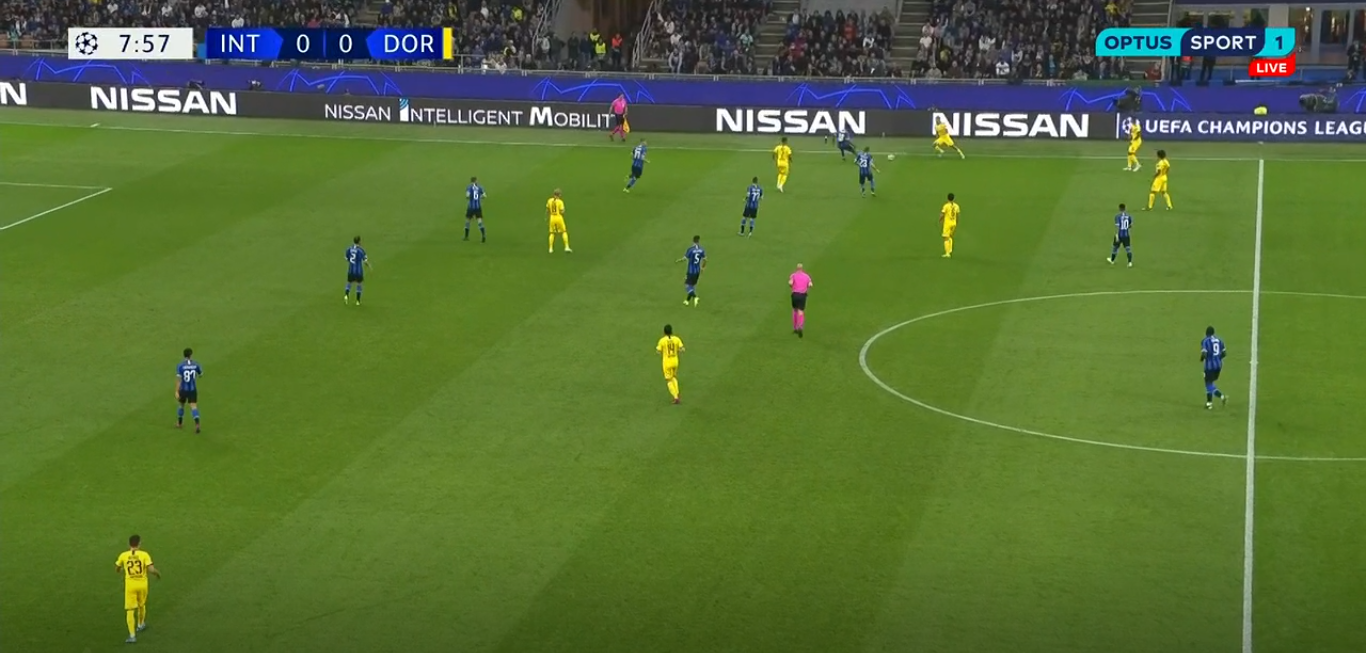

In both above images, there are at least four players available to receive a pass or cross. Both strikers and both offensive midfielders are always in dangerous attacking situations, along with the wingbacks providing width, essentially creating a 3-1-4-2. Note in the first image how close the central midfielders are to the strikers

In his first game against Lecce, while using Marcelo Brozovic – previously a standard box to box midfielder – as a deeper-lying #6, he essentially created a 3-1-6 formation when Inter penned the newly promoted side into their own box.

The system showcased an inordinately offensive plan, in which the strikers would occupy central defenders and the midfielders would move into the space between them and the attacking wingbacks, essentially meaning the opposition midfielders would have to track back into their own box or risk being completely outnumbered. This effectively meant the clever, shoot-happy midfielder Stefano Sensi – signed from Sassuolo in the summer – could work his way into threatening places around the box.

In the derby against Milan, for instance, Sensi completed the most passes in the final third of anybody on the pitch.

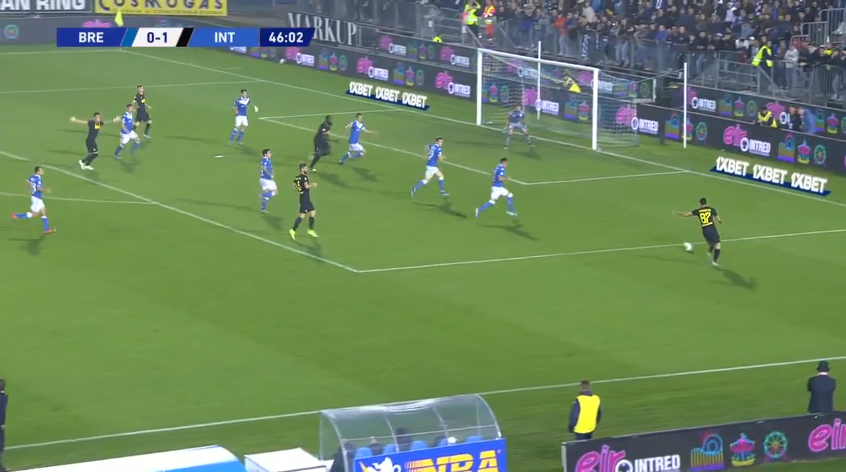

The players in the image above, directly preceding Inter’s second goal against Lecce, include Romelu Lukaku and Lautaro Martinez, the aforementioned Stefano Sensi, Matias Vecino – his midfield partner – and Antonio Candreva – the opposite wingback.

Not only are the midfielders told to make runs into the box to support the strikers, but the opposite fullback to whatever side the ball is coming from is told the same. When one considers Conte built this team around Lukaku and Lautaro’s first touch layoffs, it’s apparent how even the deepest defence would be unsettled by the sheer numerical ferocity.

However, this is not a naïve, cavalier side obsessed with attacking.

The counterweight

For the kind of marauding onslaught that Conte has innovated, he required somebody behind it all; a commandant who could dictate play and keep the team from being overrun. Marcelo Brozovic’s most impressive traits aren’t those that stand out on a spreadsheet: he doesn’t play the most magical passes, nor does he make the most tackles. Make no mistake, he does enough of both, but his true value comes in his ability to hold down an entire midfield by his lonesome.

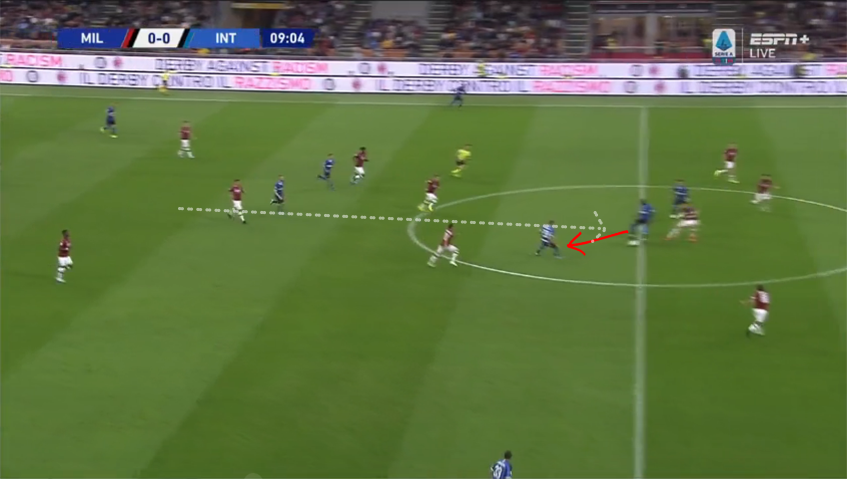

In both above images, Marcelo Brozovic is acting as the dictator, the man in the centre of midfield entrusted with spraying passes to the more advanced midfielders and forwards.

Conte’s systems all share certain traits; and one of those is the resistance to being overwhelmed. Alongside intensity, Conte prides his teams on being unwavering: it’s likely the reason that Inter have picked up the maximum number of away points in Serie A this season despite not necessarily playing their best football. The Croatian midfielder typifies this: he’s almost impervious to being pressed. However, even as the ball-playing pivot, Brozovic has assistance from behind him when it comes to building the play.

Inter love vertical passes to their front men, and none do that more often than the middle centre back, namely Stefan de Vrij.

Verticality

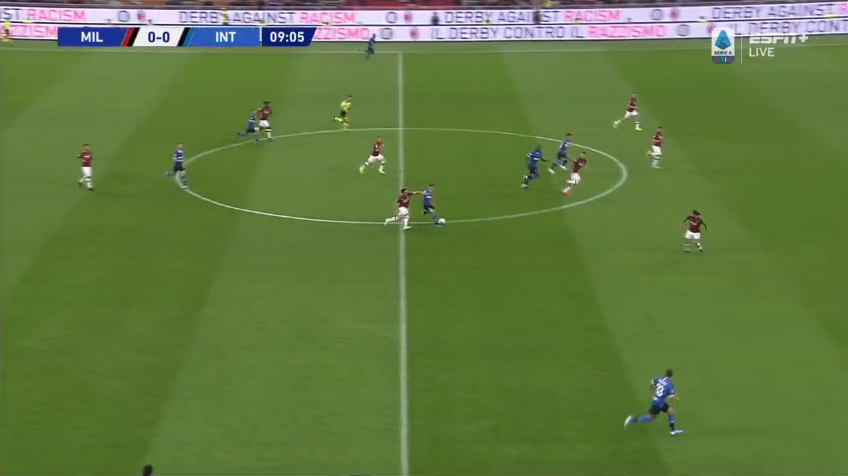

Vertical Passing is how Inter build chances quickly. Rather than building through midfield, they have the midfielders stick close to Lukaku; who is sensational at playing first touch passes off of long balls.

Inter wanted Romelu Lukaku for a very good reason. It was likely one of the conditions on Antonio Conte’s appointment, given how imperative the Belgian is to the system.

When Marcelo Brozovic receives the ball ready to spring a counterattack, or Stefan de Vrij receives the ball with space in front of him, the first port of call is to try to find Lukaku with a long pass, flat and fast and into his feet.

Why? It seems archaic, doesn’t it?

Because Romelu Lukaku is a phenomenal footballer capable of bringing the ball down and playing it quickly, dragging defenders with him as he does so. As seen in the images above, he acts as the fulcrum for the team’s attack, meaning players can run past him to collect the ball once he brings it down, and the ball can move from back to front, bypassing an opposition’s midfield, without sacrificing any tempo.

It also helps that he has an equally phenomenal partner in crime: Lautaro Martinez, whose remit is to stick tight to Lukaku and be the first to receive the ball once the Belgian brings it down. From there, Lautaro is able to beat a player, continue to interplay with an onrushing midfielder (Sensi, Barella or Gagliardini) or play it back to Lukaku.

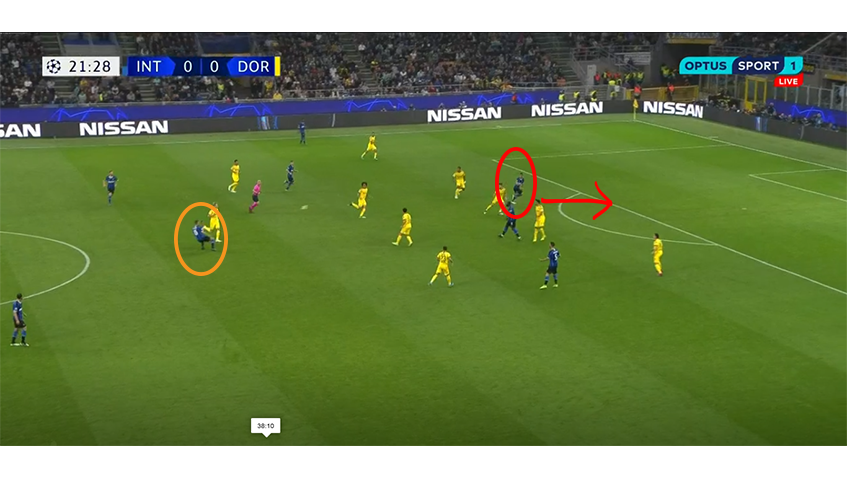

Inter’s first goal against Dortmund came with Stefan de Vrij stepping into midfield and launching a vertical ball over the top to find Lautaro, who brought it down and beat Burki. He was allowed to step through midfield because Inter had four players occupying all four Dortmund defenders.

In recent weeks, Lukaku and Lautaro have carried Inter’s goal-bearing responsibility, largely due to the fact they can fashion chances of their own making.

When it doesn’t go directly vertical, it comes from their wingbacks, who are essentially auxiliary wingers, defensive only in how far they track back. In Antonio Candreva and Valentino Lazaro (on the right) and Kwadwo Asamoah (on the left), he has truly vertical players, capable of surging down the flanks and pressing high whilst simultaneous being adept at filling their roles in a defensive setup designed to stall the opposition.

Which is where the beauty of Conte’s system really blossoms.

Regiments and Battalions

A reader would be forgiven for thinking Inter’s system is that of gung-ho, balls to the wall attack. After all, the operative word used is “onslaught.”

That’s not just an attacking onslaught, though. That’s equally a defensive onslaught, designed to wear down opposition and stifle any creativity that doesn’t come from wanton crosses. When Dortmund came to the San Siro, they barely created a chance, entirely shut down by Inter’s tight regiments.

When defending a lead, Inter are very happy to sit back in tight regiments of five and three, ensuring there’s no space between for passes to be played. Effectively, they force opposition out wide and then press them.

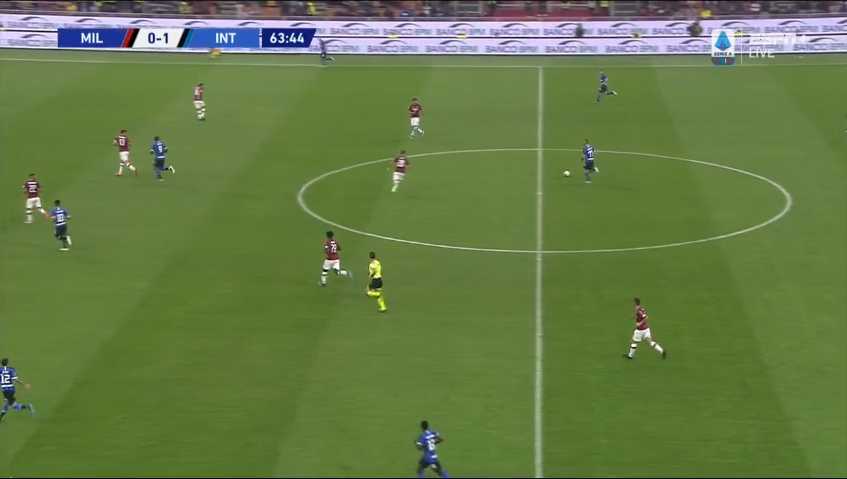

Against Milan, when Inter didn’t want to be so cavalier, only Stefano Sensi joined the attack from the midfield, essentially creating a 3-4-1-2. When Inter needed to lock things down, Conte shifted to 5 at the back, penning the fullbacks back and forcing the Rossoneri out wide, meaning it became a 5-3-2. Then they sprung a counterattack and the midfield suddenly sprung to life again, Nicolo Barella joined the attack, got in behind the fullback, and it was 2-0. When Matteo Politano – one of Inter’s brightest sparks on the wing last season – came on as a substitute, it became a 5-2-3.

When defending deeper, as they did against Barcelona, Juventus and Dortmund, they regiment the back five with the three midfielders just in front of them. And when they need to defend with their backs against the wall, they can call on the prowess of Diego Godin and Milan Skriniar – two of the world’s best.

When they don’t have the ball, Conte’s team is tactically drilled, meaning the opposite fullback (Candreva, in this image) drops to cover any switch of play while his opposite number (Asamoah) presses up to the midfield to win the ball.

This ability to switch between obliterating attack to a defensive battalion is the result of tactical flexibility on behalf of the manager and tactical versatility on behalf of the players. It is not something that comes easily, either.

And, while Antonio Conte continues to complain about not having enough players, it can’t be overshadowed how much Inter have changed in the space of a few months.

They were previously shambolic, subject to the whims of an angry bald man, an Argentinian diva, and that diva’s wife. Now, they’ve got adults in charge, they’re challenging Juventus – despite losing the Derby D’Italia – and they have one of the most tactically astute systems in Europe.

Not that it’ll stop Conte from complaining.

By: Alex Barilaro

Photo: Gabriel Fraga