Tactical Profiles: Julian Nagelsmann’s Leipzig

German football has often emulated German culture. There is a priority on the system, on fluidity and smoothness, on the collective mattering above all else. In a country that brought the term “expressionism” to the fore in 1920’s cinema, there is a distinct lack of expression allowed in German football. The team comes first so that the team can come first.

The current beacon of German excellence is Julian Nagelsmann. He’s taken the traditional German philosophy and innovated it, improved upon it.

Calling German football “mechanical” used to be a slight. Under Nagelsmann, it’s a compliment. Nagelsmann has created a machine in which every one of its components knows exactly what to do, and therefore every single player is made to look exceptional.

This machine is beautiful.

The man at the helm

It shouldn’t be surprising that Julian Nagelsmann is the youngest ever Bundesliga head coach to reach 100 games in management. He was 31 when that particular milestone was achieved, having taken over at Hoffenheim in October 2015 as a 28-year-old.

His masterful touch involves much more than tactics: he’s a proponent of the idea that coaching is more than just the instructions you give your players, but the bond you cultivate with them. He’s an astute man manager whose chief success comes from assigning every one of his players a role in which they can thrive.

But to downplay his tactical nous would be incredibly stupid.

The formation

There’s an important first question. Which formation is “the formation”?

Fundamentally, it’s the 4-2-2-2, because that’s what most accentuates the team’s fluidity. But at Hoffenheim, the young German preferred a 3-5-2, which he’s retained at Leipzig.

Against Bayern he went with a slightly more centralised 3-3-2-2, with his two fullbacks tucked in beside Konrad Laimer in midfield.

During the Champions League group stage, Nagelsmann went with his regular 4-2-2-2, yet in the 3-0 victory over Spurs he deployed a 3-4-2-1 that matched Pochettino. In the 5-0 victory over Schalke, meanwhile, his full backs played much higher than normal and in the 2-2 draw with Gladbach, it became more of a 4-4-1-1.

All of this is to make a simple, yet important point. Formation does NOT mean system.

The genius of Nagelsmann is in that fact: his system, of control and counter-pressing, of solidity and swift ball movement, is reliant on every single player knowing exactly what their job is. Every single player looks better than they are, because the system allows them to shine, and yet the system can materialise in so many different ways.

Willi Orban and Ibrahima Konate were injured early on in the season, so Lukas Klostermann and Marcel Halstenberg (both nominally fullbacks) rotated roles in the heart of defence.

Then Nordi Mukiele, nominally a centre half, was deployed at right full back. And when Diego Demme departed for Napoli, Konrad Laimer became the constant in midfield with everything augmented around him.

The formation is flexible, but the system is a constant.

Beware the onslaught

It may seem tenuous to link such a programmed automaton to any form of music, but the best way to describe Leipzig’s style is in terms of a symphony.

There exists a tempo and rhythm, light violin with a deep bass drum, perhaps, which lulls its audience into a false sense of calm, of a settled, looming beat that then erupts with a sharp fervour at any moment. Suddenly there are about a thousand drums, the violins are reaching a violent crescendo and everything seems so intense.

It’s when Leipzig seem settled, seem resolute to be patient and controlling, that you know the onslaught’s about to come.

Often it comes via the shape itself; a 4-2-2-2 is narrow, especially with Marcel Sabitzer, Christopher Nkunku and Emil Forsberg usually trying to get in between the lines. When everything seems central, Timo Werner pulls wide.

He’ll drag a defender out of position, receive the ball, then turn and burn him in a one on one. Or he’ll hold onto the ball long enough for one of those attacking midfielders to come support him, while a fullback sears into the vacated space out wide: after all, Leipzig were all congested just a second ago.

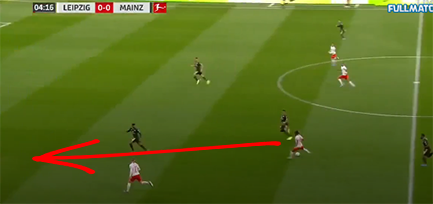

On the counter, Leipzig’s widest player is Timo Werner, who stretches the defence and tries to get outside the fullback. The two attacking midfielders being central occupies the defender’s attention, allowing Timo the space to move into.

When Werner gets one on one with a defender, as he did preceding the above picture, the dilemma is whether to show him outside, where he could burn the fullback and cross, or show him inside to shoot. In this case, the fullback showed him outside; and Werner dribbled past, then slotted a ball across the face where Marcel Sabitzer could score.

Werner has 21 goals and 7 assists in 25 Bundesliga appearances this season. But to call him the only danger would be a grand disservice to the entire system.

If an opposition team (like Monchengladbach, for instance) presses them so busily that they have no time to even play simply lay-offs and one-two’s, then they’ll make everything more compact and play balls over the top of the defence through Dayot Upamecano and (the injured) Ibrahima Konate.

After all, in Werner, they have a hybrid winger/striker, capable of both dragging a defender wide and getting in behind. He likes making runs on the outside of the full back, forcing them away from any midfield support.

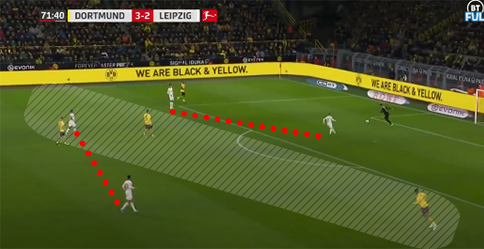

When a team tries to compress Leipzig, as Dortmund are doing, they look for the long pass over the top, where Werner likes to make his runs to get the defender 1v1.

In Youssef Poulsen he has a partner capable of both holding the ball up AND dribbling with it, a unique combination that suits Werner’s desire to move into space where he can take a defender one on one: if Poulsen’s dribbled past one already, and has another coming to stop him, then Werner’s ready to strike on whichever one’s left.

Patrick Schick meanwhile is the perfect foil to Werner receiving the ball out wide; Schick is a penalty-box striker whose scoring ability came to the fore around January, (when he was favoured to Poulsen) allowing Werner to stretch the defence while still having Schick to occupy the dangerous areas.

Locked down Werner? Schick might get free. Compact in defence? The fullback will have space into which they can gallop. Pressing them high? They’ll just go over you.

Just when Leipzig have their opponents lulled into a soft, melodic harmony, the guitar kicks in and everything suddenly turns very heavy metal.

One’s a gun, the other’s a pocketknife

In analysing just how well-drilled Nagelsmann’s system is, two positions stand out most of all: the two attacking midfielders.

They have to be malleable, given how often Nagelsmann switches shapes, and they’re integral to the way everyone else moves. In a 3-5-2 or 4-2-2-2 they act as half-wingers that stay tucked in, and yet they often drift wide to create overloads when the fullbacks push up.

They also receive the ball from the centre halves, with back to goal, and play into the feet of someone like Konrad Laimer, who then sets the attacking quartet on their way. They act as both the pivots and the hammers.

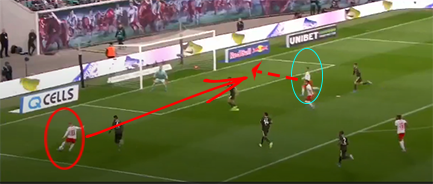

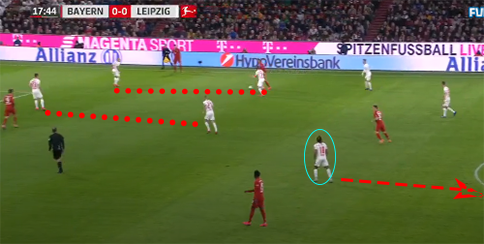

Sabitzer has come deep – in line with the midfield – to receive a low ball at his feet from Klostermann. He’ll play a first-time pass to Konrad Laimer, having already dragged his marker out of position.

First is Marcel Sabitzer, with 12 goals and 7 assists in 31 appearances this season. His goals come from all different kinds of runs, too.

When someone like Poulsen holds the ball up, it’ll be Sabitzer who makes a run in behind, forcing a midfielder to either follow him or hope the defender’s picked him up.

If Werner goes wide to collect, Sabitzer will often ghost into the box, ready for a cross or a cutback.

If Werner is one on one, Sabitzer will occupy one of the centre halves to ensure Timo isn’t outnumbered, and when the build-up needs to be more methodical, he’ll drift wide and act as a kind of winger, stretching the play.

Sabitzer is devastatingly effective where you don’t expect him to be; a pocketknife that can be produced at the most opportune time. His partner in crime, meanwhile, is slightly more overt.

Nobody picked Christopher Nkuku to become a proxy-striker when he first departed Paris St. Germain, but then a lot of what Nagelsmann does is rather unorthodox.

Where Sabitzer will often appear out of nowhere, his French counterpart will steamroll through the midfield, then combine with his strikers and get in behind all on his own.

Against Zenit, he even played up front.

Timo Werner comes deep to receive a pass through Leipzig’s midfield, and Christopher Nkunku is making the run past the centre forward and in behind the defence.

But again, this is all part of the system. When Werner drags a defender out, it’s up to Nkunku to be his support, just as it is to overlap Schick or support Laimer in winning the ball back.

He’s direct, but where Sabitzer is more insidious with his movement, Nkunku will blitz into the edges of the box and play the killer ball: he’s registered 12 Bundesliga assists this season, with 4 goals to accompany them. Meanwhile there’s Emil Forsberg, whose role has shifted, but who remains integral to combining with the strikers.

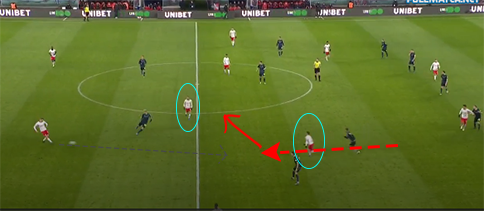

Even when Leipzig don’t have the ball and are pressing, one of them will be always be waiting on the opposite side to the press, ready to spring the counter.

Against Bayern, with the side very much pegged back and pressing, one of the attacking midfielders (in this instance, Nkunku) acts as the out ball, staying just above the press to quickly counter.

Off the ball, they’re still very German

Regarding pressing, Leipzig are still a very German outfit. While it’s not quite the manic relentlessness of Ralf Rangnick, Nagelsmann’s upbringing in the realm of counter-pressing and transitions is telling in the way his side acts.

Similar to the way they’ll lull opposition into believing that everything is rather settled before ramping up the speed in attack, they won’t necessarily look to lose the ball just so they can immediately win it back.

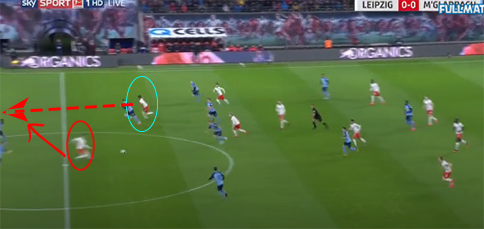

But when the opposition does look to build from defence, for example, both strikers will harass the centre halves, while their reinforcements block off any short, central pass.

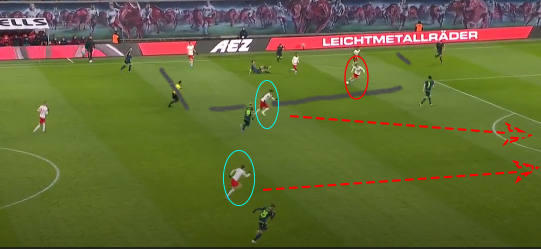

As detailed above, the two strikers press the keeper and cut off passes to the centre halves, while the attacking midfielders prevent any short passes to build play. The result is that Roman Burki is forced into going long.

The aim is to force them wide or force them long. Forcing them wide means one of Angelino or Mukiele can press vertically, while one of the attacking midfielders presses horizontally and a striker comes from behind.

Forcing them long obviously means there’s a good chance Leipzig will win it back and be able to play straight back between the lines, or recycle possession and get back into that unsettlingly controlled rhythm. When they do lose the ball, they’ll often force the opposition out wide and press the ball carrier.

Having won the ball back (in the small box marked out by the grey lines) with a three-man press, Werner dribbles and the midfield move to offer the killer balls. Leipzig can be devastating on the counter when they want to be.

Most of the time, it’s the former: Leipzig are still blistering on the counterattack when they want to be. Werner is the ideal weapon for that, of course, but so is the system itself.

Konrad Laimer is the underrated champion of the lot: against Bayern he acted as the sole link between the five-man defence and the four-man attack, while he and Diego Demme would be the most active pressers when it came to winning the ball back high up the pitch.

With Demme’s departure, Laimer has flourished as the foundations of Nagelsmann’s midfield, the basis from which four or five players can launch counters.

So, Leipzig are still German in essence. But that essence had been upgraded, innovated upon by a visionary young manager.

They may not be ready to be Bundesliga champions just yet. But Nagelsmann certainly will be a champion, one day.

By: Alex Barilaro

Photo: Gabriel Fraga