The Utility of the 3-2 Build-Up Structure

The 3-2 build-up structure entails having a consistent back three with two players ahead. This typically manifests itself either in a 3-4-3, where the three centre-backs and two midfielders ahead form the shape, or in a 4-2-3-1 where one full-back adapts his positioning to create the back three, while the double-pivot forms the midfield two.

The fundamental difference between these two formations is in the symmetry; the 3-4-3 is more balanced because the wing-backs sit at the same position on both flanks. In contrast, the 4-2-3-1 is more asymmetrical because it forces one full back to tuck in, thus causing an imbalance as one full-back is deeper than the other.

This article will discuss the benefits behind playing with a 3-2 build-up structure as well as its weaknesses, while also analyzing how different variations of the 3-2 can alter other aspects of play.

Consolidating Possession and Creating a Launching Pad for Attacks

The 3-2 shape allows teams to achieve something vital during the build-up phase – deep central possession. Deep central possession is essential because it makes it more difficult for the opponent to remain compact while simultaneously covering the length of the pitch, which is required to prevent progressive passing options, or passing options which subsequently lead to the opening of progressive passing options.

By maintaining this deep central possession, teams have far more passing options in the middle and thus do not have to resort to playing through the flanks. If the team was to play through the flanks, the opposition would have a far easier time of pressing them and constricting space, as the touchline acts as a natural barrier.

In other words, a left back can either pass sideways, pass diagonally, or pass backwards, or attempt to dribble their opponent. On the other hand, a player in the middle will have a panorama of passing options, and will force the opposition to commit more numbers in order to effectively press and disrupt the build-up.

The back three allows for numerical superiority against the first wave of defensive pressure, thus allowing for greater control in the first phase of build-up. This advantage can be enhanced by one of the double pivot players dropping back when necessary, resulting in a free man being available for a shorter pass, thus facilitating greater ball retention.

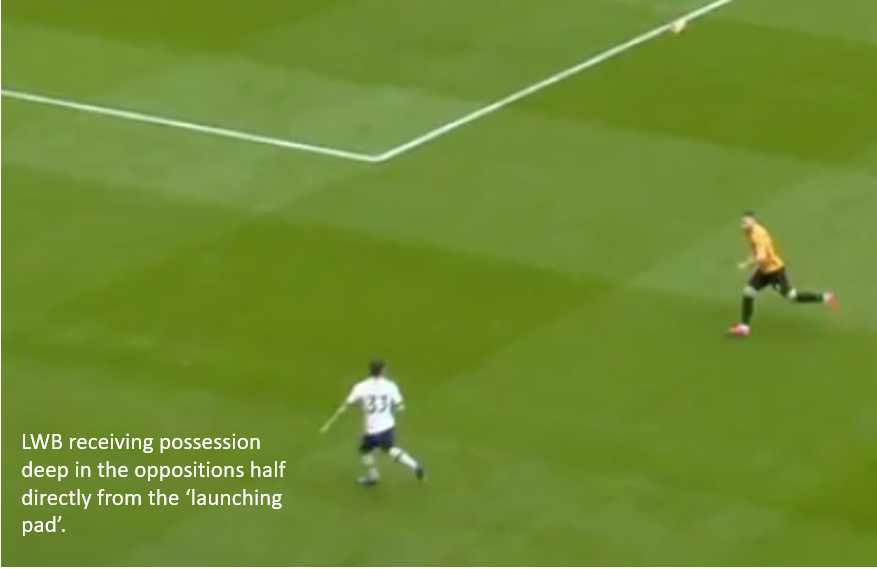

The deep central possession that is enabled by the 3-2 results in the wing-backs having time and space, as the opponent must prepare for the possibility of the ball being shuffled to either flank. Therefore, a major advantage of the 3-2 build-up shape is that it creates a viable route for consistent ball progression – by capitalising on imbalance in wide areas.

The 3-2’s deep central possession complicates the opponent’s press — if the opponent commits too many men forward to press, they risk being exposed on defense if the team plays out of the press. If the opposition presses the back three, they in turn create space for the wing-backs to receive and go forward. Consequently, pressure is less effective because there is constantly a player in space acting as a passing outlet.

When it comes to nullifying a 3-4-3, a plausible solution is for full-backs to mark wing-backs tightly or to position them high up so that they can trigger the press when the wing-back receives the ball. However, that man-oriented approach can lead to space being exposed when an individual duel is lost, thus increasing the chances of numerical disadvantageous situations, should the press be bypassed.

The team in possession using the 3-2 are at an advantage because even numerical parity in advanced positions can leave a defence dangerously exposed for direct attacks. Once the press is bypassed, the attacking team immediately has the advantage over the defending team.

The 3-2 creates situations where restricting the size of the pitch is difficult for the opposition, and wing-backs are afforded time and space whether or not the opposition decides to press. The consolidation of possession, providing that players are skilled on the ball (Neves, Moutinho and Coady are a notable example in a side which uses a 3-2) creates a launching pad for direct attacks. If you sit back, they can still advance possession through their passing; if you press them, they can still play out of the press via their passing.

Protection Against Turnovers

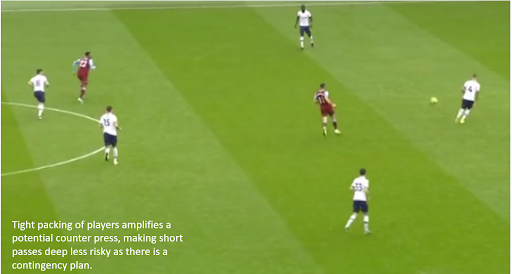

The 3-2 shape inherently prepares against the possibility of a quick turnover, making it more suitable for press-baiting and attempting high-risk passes to capitalise on extra space. This is due to the central compactness of the centre-backs and central midfielders during the build-up, which allows for vital areas of the pitch to be protected, particularly if possession is lost via a direct pass. If a player misplaces a pass and turns it over to the opposition, the team will be able to react quickly to the turnover.

Furthermore, a back three in possession, as opposed to a standard two centre-back setup, allows centre-backs more freedom to be aggressive. Rather than a back four, where a center back would only have one partner helping him, the additional two center backs allows the defender to act more aggressively. Whether the defense is aiming to intercept possession or force the opponent to shuffle out wide, this 3-2 protects the defense and prevents the immediate threat of the attack.

This shuttling is particularly effective in a 3-2 shape as there are five players positioned centrally, allowing for quicker adaptability to defend the flank that is being attacked. A potential weakness in this system is the increased danger caused by a switch of play; however, under ideal circumstances, the wing-backs will have recovered or the defending five will have pushed the opponents wide enough to nullify the threat.

With regards to the 4-2-3-1, asymmetrical attacking is often used to create overloads while also keeping players back on defense, as the tight gathering of players provides security for a turnover if short passing fails. If a team attacks mostly through the right flank, they will have more players on the right, causing there to be less space and complicating the opponents’ counterattack.

If the opponents manage to evade this pressure and progress their counterattack, they can easily switch play to the winger on the opposite flank, taking advantage of the 4-2-3-1’s asymmetry. Should a turnover occur on the isolated flank, there are three defenders and at least one midfielder covering and providing security.

This solves the attacking width conundrum — the team can maintain attacking compactness on one flank, while also stretching the pitch with the isolated winger taking up the other flank. If the opposition does succeed in countering and switching play to the isolated flank, the 3-2 defensive structure will allow the defense enough protection to respond to the counter-attack.

Fundamental Differences Between the 4-2-3-1 and 3-4-3

Firstly, dealing with formations in the abstract can be difficult as shapes themselves do not dictate a style of play, but instead influence what can be expected. Thus, the discussion below is predicated on overviews and expectations which can be anticipated to manifest because of a chosen shape.

Regarding the teams, the primary influences behind this discussion were José Mourinho’s Tottenham Hotspur (4-2-3-1) and Nuno Espírito Santo’s Wolves (3-4-3), although the same conclusions could be extrapolated for any team playing a 4-2-3-1 and any team playing a 3-4-3. The differences between these systems, as mentioned in the introduction, relate to balance, with the 4-2-3-1 being more asymmetrical compared to the balanced and symmetrical 3-4-3.

A primary motivator behind using the 4-2-3-1 with the 3-2 build-up shape is to compensate for the weaknesses, and to accentuate the strengths of certain individuals. Examples of this include Roma under Luciano Spalletti where Juan Jesus (centre-back) would tuck in from left-back and Alessandro Florenzi (winger) would position himself in a more advanced position offensively. Another notable example is Spurs under Mourinho, who presumably wants to maximise Serge Aurier’s ability while also minimising his defensive responsibility.

This consequently leads to differences in how the teams attack, and therefore, how they build their possession. Most of the discussion thus far has focused upon creating advantages for verticality; however, because of the deep central commitment of players, that verticality often manifests itself in direct play rather than playing in between the lines. Therefore, a primary weakness of the shape is its dependence on having passing outlets who can consistently receive possession and advance forward.

The wing-backs, as previously mentioned, can often receive possession with regularity, however, they are easier to confine for an opponent and can thus become isolated and forced into a turnover before the opportunity to move forward effectively presents itself. This is more notable in the 4-2-3-1 because there is often a lack of direct progressive wide options, as the attacking shape resembles a 3-2-5, which can greatly reduce the amount of passing options.

The 4-2-3-1 becomes a 3-2-5 because the asymmetry of the full backs leads to asymmetrical wingers. The winger on the side of the defensive full-back stays wide to provide width, while the winger corresponding to the attacking full-back tucks in and acts as more of an inside forward.

Conversely, in the 3-4-3, both full-backs act as outlets, therefore the direction of play is less predictable and less positional compensations have to be made – i.e. a winger has more freedom to roam rather than having to fill the positional requirement of hugging the touchline.

However, the 4-2-3-1 provides more options to play between the lines than the 3-4-3. The attacking midfielder can roam around to support play and link passes between the lines, thus making progression more dynamic and less reliant on direct play.

This option is not available to the 3-4-3 as the striker must stay central during build-up to receive possession from a direct ball if necessary. If the striker in the 3-4-3, Raúl Jiménez in this case, attempts to drop deep to receive, he would find himself isolated and starved of passing options to combine with, thus allowing the opposition to easily press him and force a turnover.

In contrast, a striker in the 4-2-3-1, Harry Kane in this case, would have an attacking midfielder to run in behind and alleviate pressure. The extra man, Dele Alli in our scenario, improves the probability of the team winning second balls resulting from a long ball, as a strong centre forward can occupy the centre backs and/or provide a flick on which can allow the attacking midfielder to capitalise on space in behind.

This can also manifest itself as a header backwards for the attacking midfielder to win the second ball, where the onrushing wide players (possibly the attacking wing-back) have space due to the requirement of the opposition to defend the full length of the pitch because the central possession and constant width provided by the 3-2.

Moreover, the fluidity of the attacking midfielder can often allow for the creation of beneficial circumstances seen in the 3-4-3, as his movement can bring parity out wide when required. Nevertheless, when compared to a 3-4-3 or a 4-3-3, the 4-2-3-1 can often be unbalanced due to the attacking midfielder taking up the wrong position. Players are humans, not robots, and they are not always going to make the right decision that would most benefit the team.

This is why the 3-4-3 tends to be more balanced, as it has a structure which permits consistent wide balance, whereas the base structure of the 4-2-3-1 encourages attacks to be focused down the flank with the structural numerical advantage.

Successful Examples of the 3-2 in Attack

The attacking dynamics as shown above were demonstrated with the Kane/Dele partnership. This is because of the threat Dele provides as a runner while being proficient at distributing to wide areas, making him suitable to receive either a flick on a second ball.

Kane is equally capable of both while having better hold-up play (and also being more likely to win an initial duel), meaning Spurs can maintain similar problems for the opposition with regards to horizontal compactness in more advanced areas, as their two central players are great at exploiting gaps either through passing or movement in behind.

However, when Kane was unavailable due to injury, the responsibility falls on Dele’s shoulders to play as the centre forward. In the above scenario, Spurs were unable to replicate similar levels of attacking performance, as their main outlet had been removed. Thus, much of the direct play in a 4-2-3-1 using a 3-2 shape is contingent on having a striker capable of winning aerial duels to compensate for the lack of two wide outlets, as seen in 3-4-3.

As seen with Raúl Jiménez at Wolves, having a strong physical profile is also beneficial for a centre forward in a 3-4-3. Moreover, the striker in the 3-4-3 is expected to drift wide, completing the same function of an attacking midfielder in the 4-2-3-1 with regards to supporting wide overloads, with the striker in the 4-2-3-1 typically remaining more central, acting as more of a target man.

However, Kane proves that the role can be more complex when it suits the individual, with the England striker often dropping deep to help with chance creation. In both instances, a striker capable of linking up play is crucial to the system clicking, which demonstrates that it is indeed crucial to the 3-2 shape overall.

Conclusion

To conclude, the 3-2 creates a centrally compact unit responsible for build-up, which can frequently lead to detachment of play due to the deep commitment of five players. This means that members of the 3-2 are often a launching pad for direct attacks. In a 3-4-3, the typical avenues for progression are out wide, with the team attempting to take advantage of the wing-backs’s positioning, which practically makes them a constant outlet, with the potential for additional progression through linking up with the centre forward and corresponding winger.

In a 4-2-3-1, due to the lack of balance required to create the 3-2 shape, wide progression is only consistently viable on one flank, making the attacks more predictable. However, it provides more avenues for vertical progression due to the attacking midfielder’s ability to roam and support play when required, and potentially become the beneficiary of a long pass in behind.

A potential issue with the shape is its tendency for possession to stagnate, where the opportune moment for verticality never arises due to an opponent’s reluctance to press high, and effective confinement of the wing-back or wing-backs. The shape’s primary strength is its ability to maintain central possession and challenge the opponent’s defensive compactness.

By: @mezzala8