Using the Touchline: A Deep Dive Into Rangers’s Pressing Scheme

After a decade of mediocrity that saw them languish in the shadows whilst their eternal rivals established an unprecedented hegemony in Scottish football, things are looking up for Rangers. Steven Gerrard’s side currently sit 13 points above Celtic (who have two games in hand), and after finishing atop a group of Benfica, Standard Liège and Lech Poznan, they will face off against Royal Antwerp in the Europa League Round of 32.

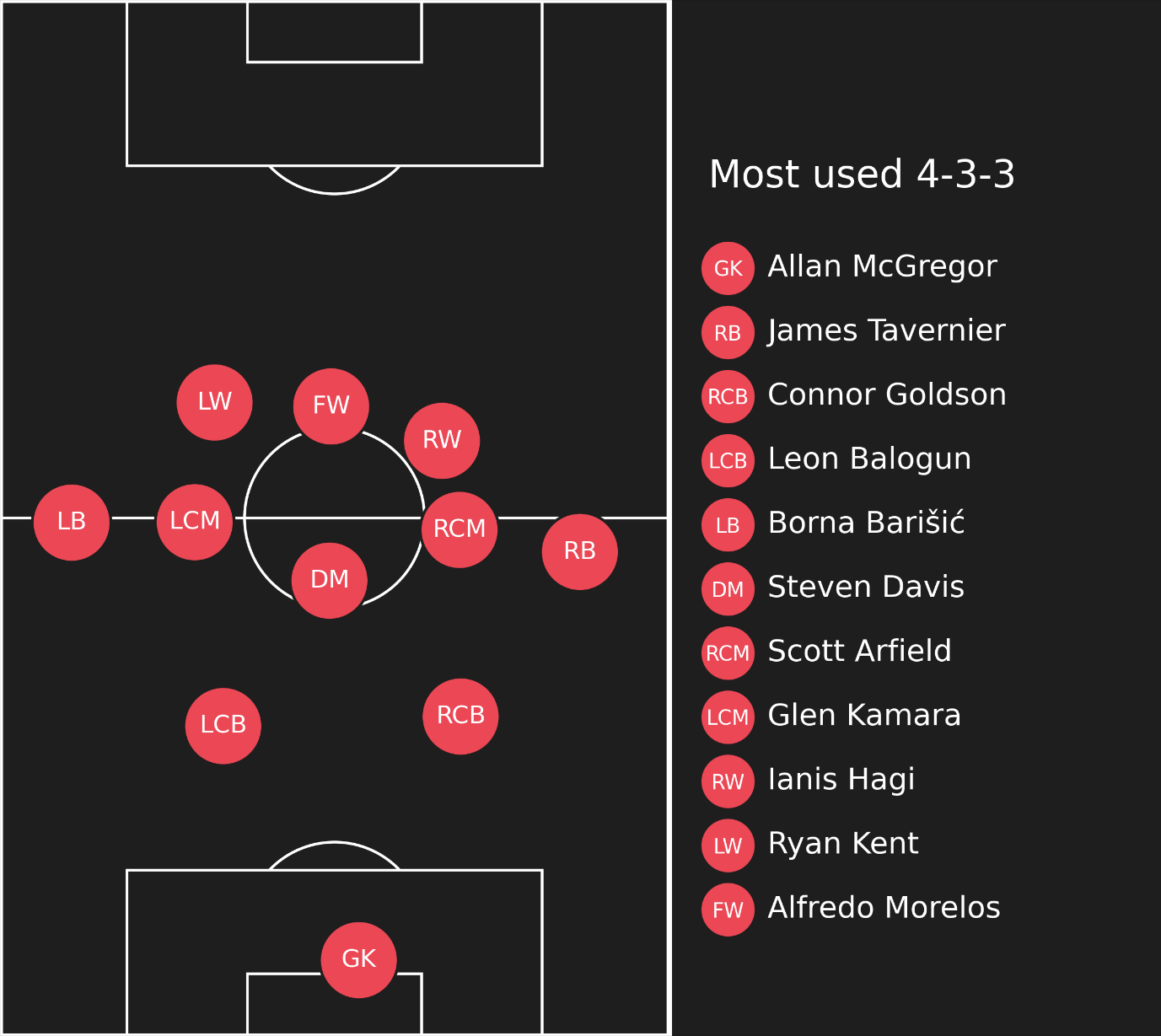

Rangers typically set up in a 4-3-3 both in possession and off the ball, with Ianis Hagi and Ryan Kent partnering Alfredo Morelos in attack. This narrow 4-3-3 shape helped contain attacks and provoke advantageous attacking situations, as Rangers took four victories and two draws in their Europa group, scoring 13 goals and conceding just 7.

Photo: Twenty3 / Wyscout

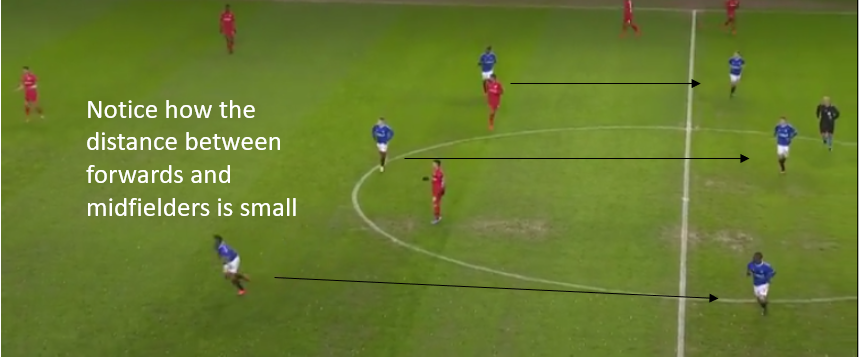

As seen by the average positions in the Europa League group stage, Rangers’s front three typically shift inwards in order to minimise space in between the lines and make it difficult for the opponent to establish destabilising connections. The two lines of three remain horizontally compact so as to prevent the opponent from building centrally, thus directing play out wide.

This allows for exploitation of the constraining effect of the touchline in order to reduce the size of the effective space, with their full-backs pushing high to support the other players on the flank where they maintain compactness horizontally through the process of shuttling and achieve greater coverage of the effective space. The centrality of positioning off-the-ball limits the opponent’s alternatives forcing them to go wide if they seek to play short, therefore playing into their strategy.

This structure allows for the creation of pressing traps, where Rangers can quickly establish numerical superiorities. A pressing trap refers to the deliberate opening of spaces to entice the opponent only to subsequently apply pressure in that zone in a premeditated manner. This occurs centrally because of the potential convergence of the two lines where pressure can be applied quickly and aggressively due to the emphasis placed on vertical compactness.

This makes reception difficult, producing a potential turnover. Should the opponent consolidate, options are limited due to the backward movements of the forwards applying pressure while subsequently covering the deeper central pass. While turning is made difficult by the tight marking resulting in a pass out wide for the best-case scenario, where Rangers can then engage in a touchline press.

This is mostly hypothetical as the forwards typically mark the passing lanes to central players through their close positioning, forcing the opponent deeper or wider to collect. However, even if a direct central pass was possible, it is unlikely to be effective. Teams do not often build centrally around Rangers as they place significant emphasis on preventing it, meaning Rangers are often in control of the direction of play, which places considerable importance on the efficacy of their wide pressing traps.

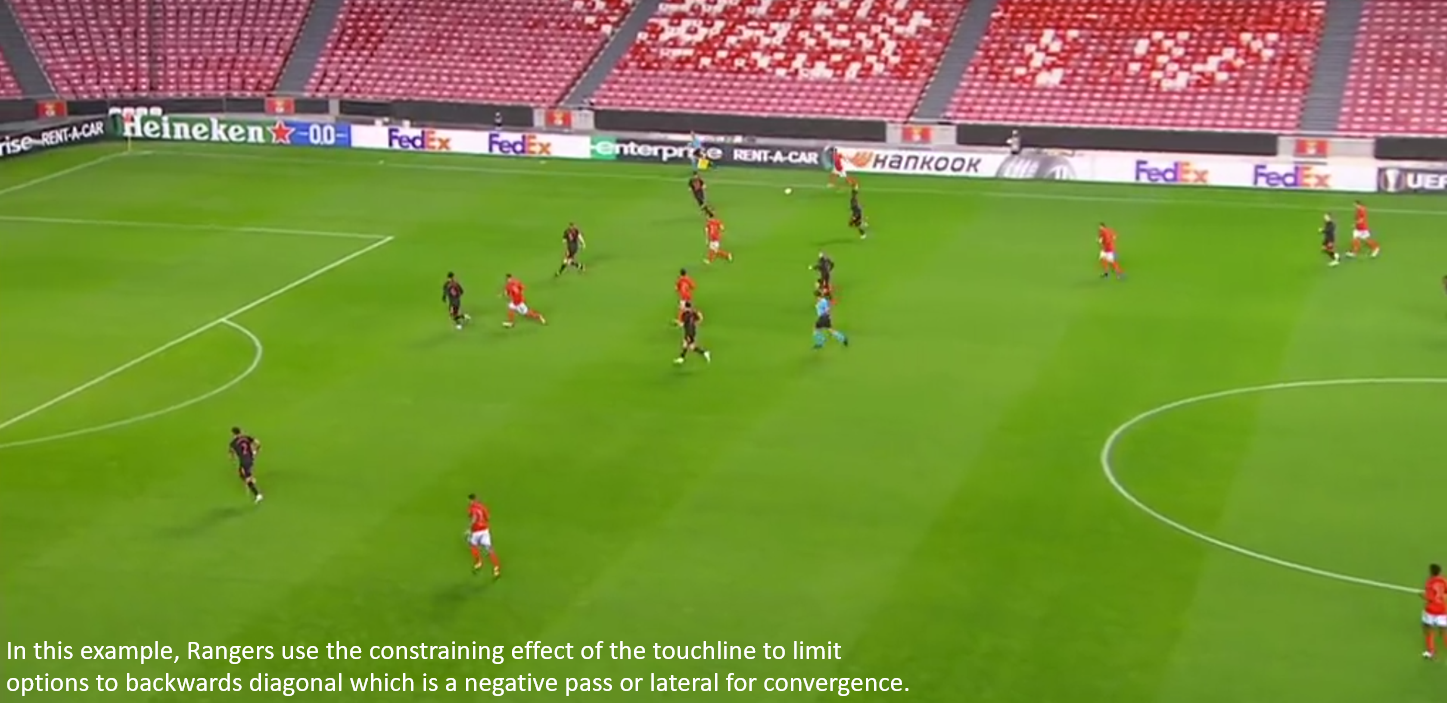

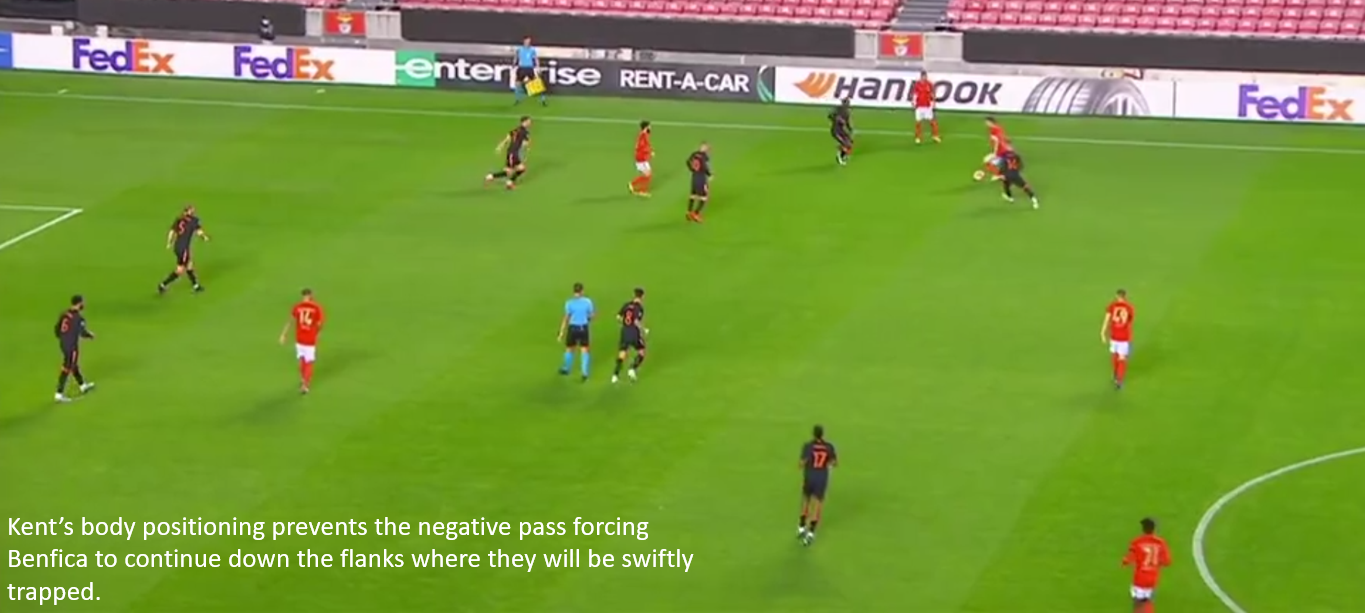

In this passage of play, Rangers allow progression down the flank, choosing to remain compact in midfield. They create a square around the two potential receivers, meaning a lateral pass for a 1-2 isn’t a viable option for maintaining possession, meaning the only option left is a negative diagonal pass which can be perceived as positive for the team out of possession. Benfica fall into the trap and Rangers regain possession.

The compactness facilitated by the touchline makes tight interplay difficult as the player in possession has limited time and options available. Rangers are not concerned with the player out wide, but his movements inwards and cover them to limit his frontier to wide/negative options, allowing them to maintain a compact block and a small effective playing area. They are happy to funnel progression down the flanks because they can effectively prevent any central consolidation through their compact midfield/defensive lines, creating pressing traps.

The ball is constrained out wide as the opposing team has no viable alternative as Rangers have garnered greater spatial control through a network of defensive connections which facilitates quick convergence when the ball is moved in between their two lines centrally.

By using the touchline to reduce the size of the effect, they can ensure it remains reduced through maintaining extreme vertical and horizontal compactness. Rangers sacrifice a significant amount of space, under the notion of limiting what is directly available to the opponent which allows for the creation of numerical superiorities within the areas of effective space they have manipulated.

The teammate can be considered the most important reference point for their pressing efforts as they look to ensure potential convergence on central players is always possible. It is predicated on the maintenance of a compact block rather than the positioning of the opponent and seeks to control the game by directing them to wide areas.

Progression down the touchline is not considered worrisome as Rangers do not view it as a means towards significant chance creation. The further the opponent progresses, the fewer options they have available due to the increased distance between them and players behind and the time it grants Rangers to prepare to press.

Kent, Joe Aribo, or whoever is defending the flanks can cut negative options further constraining as they move from the forward line (4-3-3) to a more staggered 4-3-2-1 to apply pressure whilst keeping the negative option in their cover shadow as Kent displays below.

The flat 4-3-3 thus directs play down the flanks while the staggering maintains it there. Because of their compactness, producing a negative pass is not as advantageous as it would be to other teams as it can increase the size of the effective pitch. The quicker a team can switch play the worse it is for Rangers due to their poor pitch coverage, ergo preventing the opponent from achieving situations to do so is crucial.

A potential counter to Rangers’s compact 4-3-3 press is the use of deep full-backs. This is as it stretches the backline further in comparison to a typical centre midfielder dropping and the centre backs splitting as build-up would be asymmetrical. This would force Rangers to reduce their levels of compactness to access the deep full-back in possession by pushing higher and wider but the backwards option to the keeper remains open.

This option being open grants access to the opposite flank within 2 passes which reduces the extent to which Rangers can commit to the ball side to remain compact. The obligation to press the deep full-back comes from the desire to remain compact which necessitates pressure on the ball to limit the time the player on the ball has to pick a pass to expose the unprotected space.

By seeking to stretch to the pitch vertically through having a deep wide presence, Rangers can enlarge effective space through the connection point of the keeper which cannot be cut when the ball is higher areas. Rangers would have to drop deeper to protect space in behind, which they have been willing to do against bigger sides, such as Benfica, to seek to contain them.

This provides a balance between space protection and potential turnovers by seeking to generate them in areas where numerical superiorities are more naturally occurring due to the opponent having to protect against counter-attacks. Using deep full-backs does not negate Rangers pressing efforts generally but will allow the team in possession to gain territory or expose the compactness depending on Rangers’ response.

When their compactness is exposed it forces their full-back into 1v1 duels and the centre back to be aggressive in closing opponents exposing space in behind and leaving gaps in the half-spaces deep, as demonstrated in Rangers’s 3-2 victory against Standard Liège’s at Ibrox.

For the Belgian side’s first goal, both James Tavernier and Connor Goldson were forced to step out into wide regions and were promptly beaten in their duels. Creating numerical parity in the box where Maxime Lestienne could exploit the open space through making a darting near post run which is difficult to track in a man-oriented manner, which was the organisational state that Rangers’ defence was forced into to compensate for poor pitch coverage.

For the second goal, Collins Fai was granted too much time on the ball which exposed Rangers high, retreating line through playing it into space. In both these instances, the pressure was not applied to the ball and compactness was exposed as the Rangers full-backs could not cover the space in time.

Rangers are excellent at anticipating where potential danger is and negating it. They are exceptionally coached by Steven Gerrard, as is evident by the compact spacing both vertically and horizontally.

While their adventures in Europe display a willingness to be pragmatic by placing even greater emphasis on remaining compact through not engaging as high to attempt to produce a turnover but rather attempting to control space and the opponents’ options to direct them to the advantageous wide area where they can constrain the effective pitch and contain the opponent to eventually produce a turnover.

Potential issues do exist, however, because of the lack of staggering of their front line leaving full-backs exposed should the pressure on the backline not be sufficient. Their forward line cannot remain passive, light pressure needs to be consistently applied to direct play and prevent the opponent from being too comfortable in finding the pass.

By: @mezzala8

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / Ian MacNicol – Getty Images