What is Sarriball?

Out of all the managers in European football, few have had a more improbable, unexpected rise to the top than Maurizio Sarri. He never played at the professional level, he split his time between working as a banker and playing and managing an amateur side, but in 1999, he quit his day job and dedicated himself fully to coaching. Sarri worked his way up the Italian pyramid before getting his first big break at 56 years of age, replacing Rafa Benítez as Napoli manager.

It was there at Napoli — the city of his birth — where Sarri became a ubiquitous name amongst football fans. From 2015 to 2018, Sarri’s Napoli became widely recognized for its unique style of play predicated upon verticality in possession, high-tempo passing, and circuit-based football. His team typically utilised third-man runs to either draw defenders out of position, provide a clear option for progression, or break through the opposition’s defensive block.

Whilst his subsequent spells at Chelsea and Juventus have proved to be far less fruitful, it’s only a matter of time before he gets his next opportunity at the top level. Let’s take a look at the core principles that have underpinned Sarri’s style of play and the common characteristics that comprise ‘Sarriball.’

Verticality in moving through the thirds

One of the core ideas that dictate how Sarri likes his teams to play is verticality: moving the ball “up and down” the pitch. In order to play with the necessary levels of verticality, Sarri employed a 4-3-3, which created diamonds and triangles across the pitch that could easily be manufactured and worked on in training. By having as many of these shapes as possible, one can increase the chance of having a spare man on a different line to progress the ball towards.

This does not, however, limit Sarriball to just short or even medium length passes. When the opportunity comes about by moving the opposition into wider spaces through press baiting (drawing the opposition out using short passes deeper in the pitch), the goalkeeper would play a long ball through the middle of the pitch into one of the attacking players sitting between the lines that had been moved around, allowing for swift vertical progression from which they could advance towards the goal.

This is also why Sarri prefers to have goalkeepers who are very confident with the ball at their feet. Kepa Arrizabalaga, who Sarri bought for a club record fee of £72 million at Chelsea, ranked in the 100th percentile for launched pass competition rate under Sarri. On the other hand, Pepe Reina, who started in goal for Sarri between 2015 to 2018, ranks in the 90th percentile in the same metric since the 2018/19 season. Whilst neither are particularly proficient at shot-stopping, both had the technical ability to execute the first phase of build-up.

Let’s look at this in practise. Against Real Madrid in the Champions League Round of 16, Sarri’s Napoli scored their first goal using a similar idea. The four defenders circulate the ball against Real Madrid in order to draw the Real players towards them. Once the Real players start to press, Kalidou Koulibaly at left-centre back plays a vertical pass to Dries Mertens (who operated as a false nine) who drops deep and between Real’s defensive and midfield lines.

The ball is then laid back to Napoli midfielder Marek Hamšík. Simultaneously, Lorenzo Insigne from the left wing makes a curved run straight through the middle of the Real defence. With Raphaël Varane having stepped up to follow Mertens, and Sergio Ramos being slightly further to the right than would have been ideal, Insigne was able to run straight through the middle of the defence unmarked.

Here we see another tactical aspect heavily utilised by Sarri: third man runs. In an interview, Barcelona legend Xavi said “the third man is impossible to defend against.”

The third man is a player who is moving beyond the two players who have exchanged possession between themselves. In this case, the two players who are exchanging possession are Mertens and Hamšík, with Insigne acting as the third man. As Real’s defensive players focus on this exchange, Insigne’s run occurs on the blind-side of Varane rushing into the passes.

As Carvajal is too far away from Insigne who had drifted into the half space, Insigne is free to make his run, from which he latches onto another vertical pass from Amadou Diawara, and scores with an excellent long range effort, exemplifying Sarri’s vertical style of play, orientated around quick movement of both the ball, and his players.

Another example of Sarri’s team playing vertically to players between the lines, and furthermore, using third man runs to exploit gaps created by moving the opposition around by the aforementioned passes, is when Sarri’s Chelsea went up against Arsenal in the Premier League.

In this scenario, Marcos Alonso plays the ball to Willian, who then carries the ball horizontally for a short, before laying the ball off to Jorginho, who was the “Regista” for Sarri both at Napoli and Chelsea. Here, he had slotted into the left centre back position.

Whilst this pass is being made, we can see Alonso has continued his run after having passed to Willian, and makes his run of the blind-side of Henrikh Mkhitaryan, who is not a very quick player, and so Alonso has the advantage in this scenario.

Additionally, Arsenal right back Héctor Bellerín had come inside to stay tight with Willian. After releasing the ball, Willian takes a couple more steps inside, which draws Bellerín away from the passing lane to Alonso, thus allowing Jorginho to hit a vertical pass to him.

The result of these three vertical passes and one short carry is Alonso being in a great position to hit the ball to Pedro Rodríguez, who converts from inside the penalty area. This epitomises Sarri’s style in regards to the pace of the game; quick changes in tempo to catch the opposition out, and pouncing on the chances that come their way.

Verticality is not always easy to maintain though if the correct angles are not created, and so it can come at the cost of a high number of turnovers, thus meaning that in order to sustain this style of play, Sarri’s team would need to assert themselves with both more possession and territory throughout the game.

Circuit-based methodology

Sarri is also very well known as a coach for wanting to coach using circuits. Circuit-based methods of coaching look to teach players exactly how to solve problems during training and ask them to essentially replicate it in game to reduce thinking time, and so players always have solutions, and can execute them quickly.

In the words of Arsenal manager Mikel Arteta: “Football is about habit & angles. It’s much more simple for a player if you can process the image of where your team-mate will be before receiving the ball. If I am in the kitchen and I know the glasses are always in this cupboard, I get my glass of water more quickly.”

This shows that the more you can get your players into the habit of making specific passes, and creating the right angles, the more you can reduce their thinking time, thus increasing the speed of the play and increasing the chance of breaking through the opposition.

On the whole, Sarri’s circuit based approach was most visible at Napoli, through the build up phases, where all the players seemed to know where the others would be, and they would almost always have a spare man to play through and progress through in the build up phase.

For example, in Napoli’s game against Fiorentina in 2016/17, we see the Napoli players staggering themselves across different lines, and generally inviting the press, especially with the pass back to the goalkeeper. As the ball is chipped into Faouzi Ghoulam, Diawara moves from behind the “shadow” of the Fiorentina man, in order to offer himself as an option for the man in possession.

From here, we see the ball be played vertically to Hamšík, and that Ghoulam who had the ball has now moved forward on the Fiorentina attackers blindside and can then receive the first time pass from the Slovakian captain. Hamšík then continues the run and receives it again, after Napoli winger Insigne had dropped deeper to draw his full back out to create space and move the Fiorentina defence around.

The speed of this attack, as well as the almost instinctive movements and passes of the players shows the model they work from in training and the execution is perfect, which allows them to move forward with what is essentially a 3v3 situation.

Next we can see a part of a training session in which a drill is being rehearsed by defenders. What is most noticeable here is the movement of the two “strikers,” with Paulo Dybala dropping deep, which would presumably draw the defender man marking him out of position, and Gonzalo Higuaín making the diagonal run onto the ball, after the players in the middle third had created a diamond and used vertical passes, again, to shift the ball up and down, awaiting the call of the coaches to signify an opening.

This can then be replicated in games, as Sarri and his coaches likely went through this drill multiple times in order to ensure the players could replicate it, again showing his style of coaching using circuits and repetition, as opposed to other coaches like Pep Guardiola, who it is said in his book “Pep Confidential”, never wanted to use the same drill twice, showing the stark difference between the two coaches who are said to have similar styles of play.

Flexible attack to suit needs of a game

Sarri’s teams have notably been flexible and fluid in that whilst they have a broad shape, their emphasis is not on simply maintaining positions, but rather moving beyond the constraints of a formation, and into areas which are most beneficial to the team when attacking spaces.

This allows them to better exploit the weaknesses of defensive structures they come up against, whilst still maintaining their set principles around playing vertically, quickly, and based on set patterns of play. This is displayed by, despite Sarri using the same rough formation at both Chelsea and Napoli the majority of the time (4-3-3), his teams would be able to play in a 3-2-5, a 3-1-6, or a 2-3-5, to suit what the game needed. Despite looking at specialised roles earlier, such as the Regista, this aspect requires versatility, so that players can fluidly move between “positions” in order to create superiorities across the pitch.

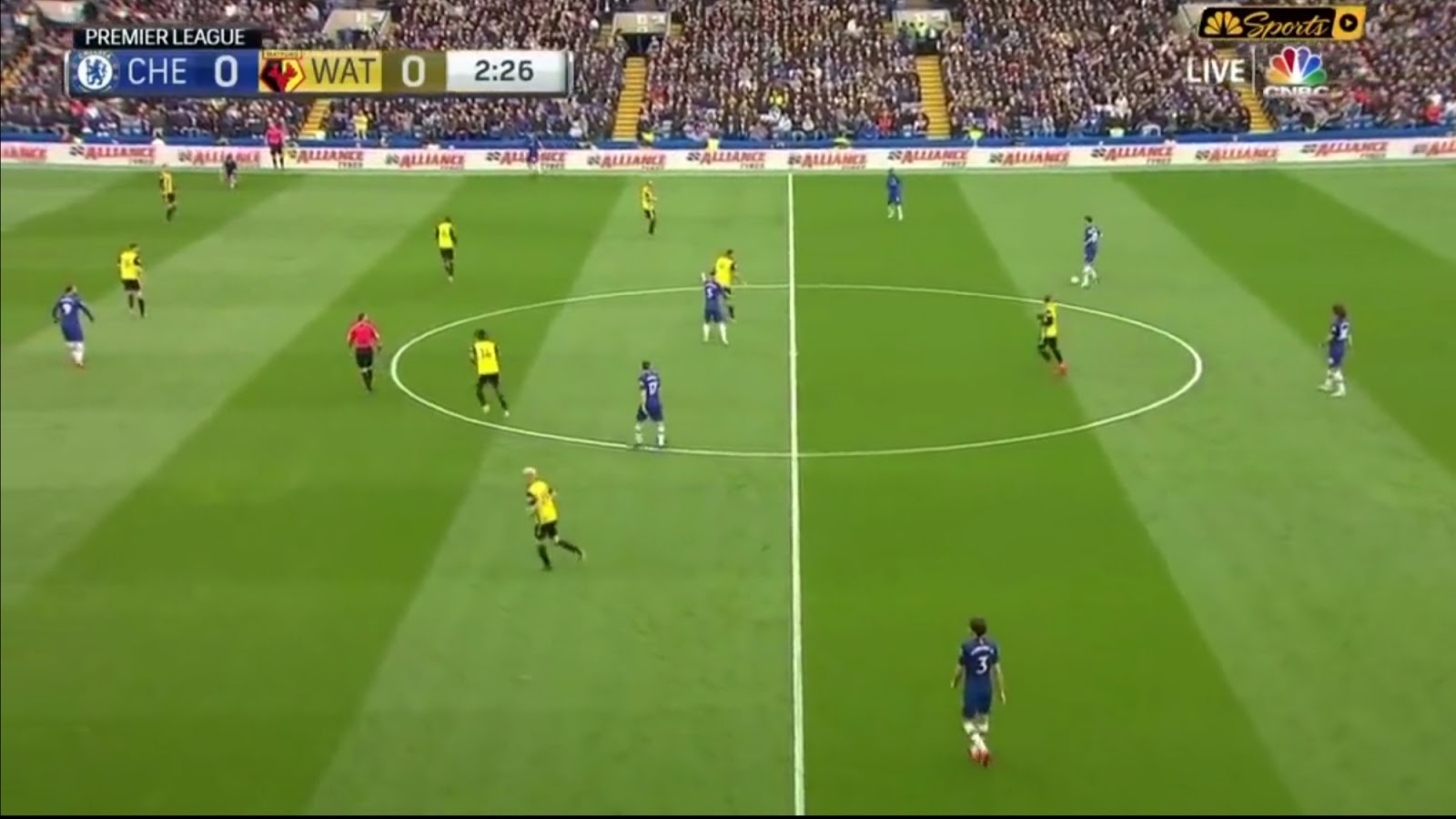

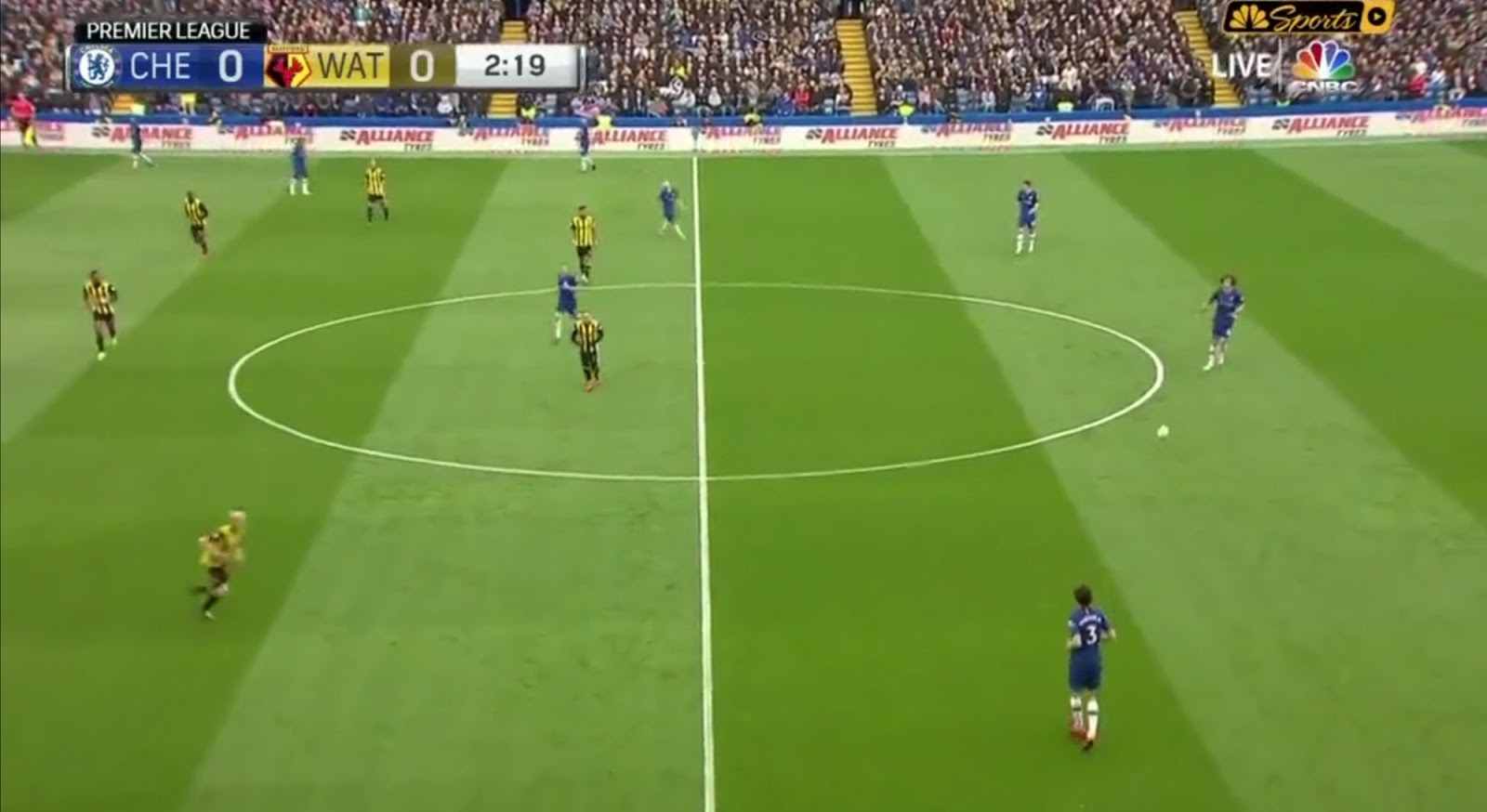

At both Chelsea and Napoli, there was an onus on one of the midfielders or one of the fullbacks, depending in the position of the ball and opposition, to create a back three in the build-up when Sarri came up against teams playing a two up-top formation, such as when Sarri’s Chelsea played against Watford for example, who deployed a 4-4-2 against Sarri’s Chelsea.

As can be seen above, the instruction of dropping into a back three would alternate to create different spaces, and try to unsettle Watford’s block. When N’Golo Kanté drops, the remaining two in the midfield shuttle across, and act as a double pivot, and match up man for man with Watford’s midfield two.

However once the ball is progressed, Kanté can be back into his position in the midfield, and then provide an extra body in midfield in order to cause overloads in central areas. Alternatively, Alonso or César Azpilicueta would drop deeper to form the three man defensive line, which would then increase the number of bodies Chelsea had available centrally.

In the below example against Burnley, who also used a 4-4-2, all three midfielders could stay in the midfield line even when building, to create a 2-3-5 structure which looked to create numerical advantages in the second phase, because Burnley were not a pressing team and so a third man in the defensive line would not be significantly beneficial.

The positioning of the three midfielder players against a two man midfield meant that there was often a spare man, who could be played through. This ability to switch through different shapes demonstrates the strengths of having flexibility in a system, whilst not only preserving the coaches core principles, but maximising them by maximising the space, as well as the superiorities available to the team in the positions required to handle situations as they arose.

This does not come without a cost though. As a result of their ability to change shapes, and adapt during the game to their opposition based on the circumstances, means that there would sometimes be defensive disorganisation at times, as a result of players not being in the position which would have prevented opposition transitions.

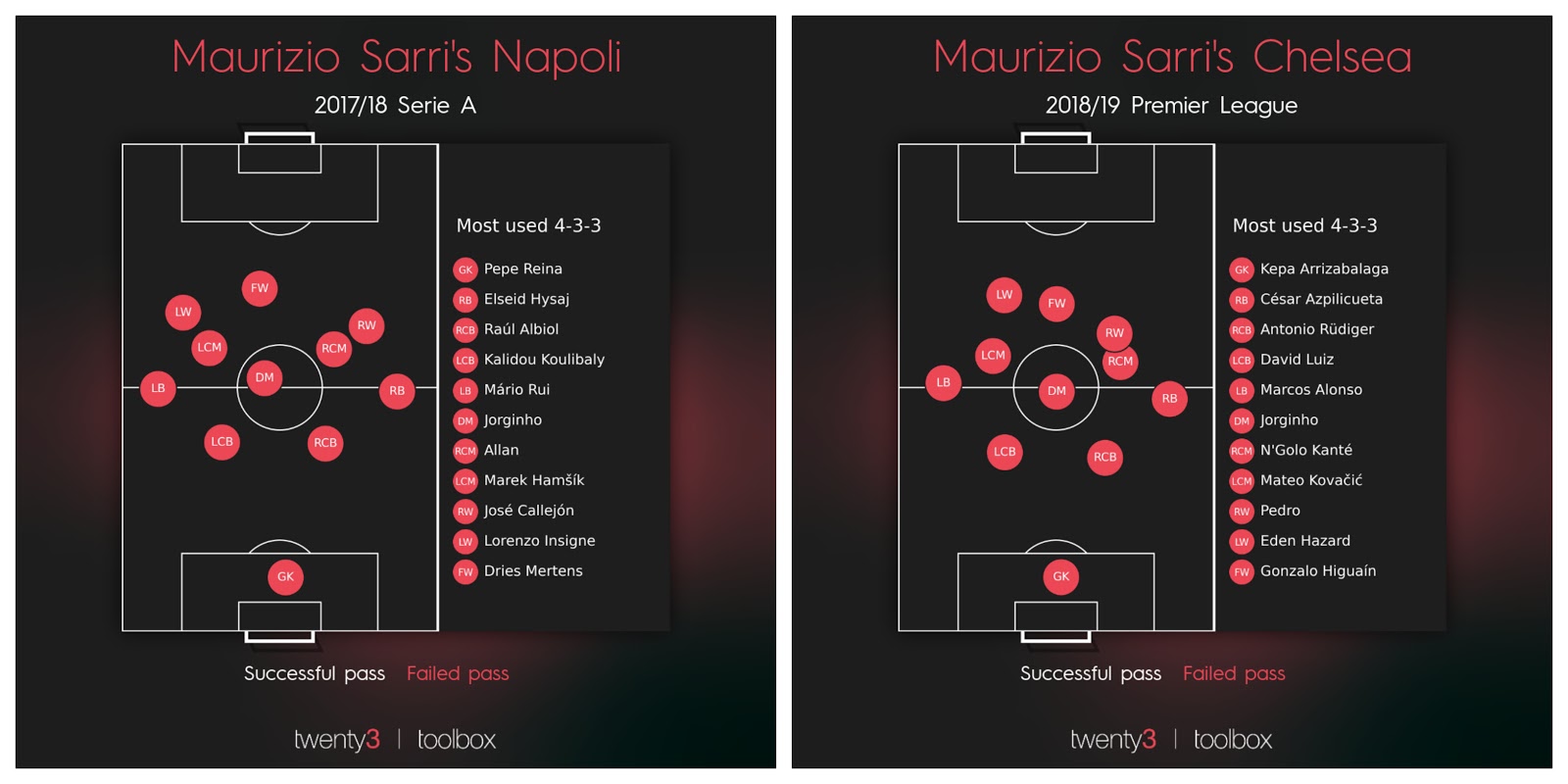

However, this is not to say that Sarri’s teams were completely fluid and lacked some sort of structure. The average position map of Sarri’s Chelsea and Napoli below both show a clear structure of a 4-3-3, showing how Sarri’s teams looked to consistently maintain a broader shape, but as mentioned earlier, were not afraid to break away from it at times.

Photo: Twenty3 / Wyscout

Another noteworthy aspect of these average positions is how they portray Sarri’s transition from Napoli to Chelsea. At Napoli, there were seemingly more coherent positions for each player, as shown by the players being slightly further away from each other, relative to Chelsea map. At Chelsea, the right-sided winger came inside more often, and the striker, Higuaín in the 2015/16 season, was often deeper than false nine Mertens.

A lot of this is down to Sarri looking to maximise Eden Hazard, who was one of the best players in the world at the time. Hazard was utilised further up the pitch than Insigne usually was, as the Belgian was usually at the centre of a lot of Chelsea’s attacks in the final third. Indeed, he contributed to around 50% of Chelsea’s goals under Sarri, showing how Sarri managed to get the best out of Hazard by making him the centre-piece of “Sarriball in England”.

Conclusion

Across this analysis, we have taken a look at the essence of Sarriball, and broken it down into its core foundations which include verticality, flexibility, and circuits. Sarriball is a style that was highly attractive at Napoli, and continued in this fashion at Chelsea and Juventus, however, on a more inconsistent basis.

Ultimately, Maurizio Sarri has managed to win trophies in each of his last two seasons, including a Europa League at Chelsea, and the league at Juventus, but neither were enough to maintain his job, and so it seems it will not be long before we see the next chapter of Sarri’s career, and thus, the next chapter for Sarriball.

The coach usually represents the image of the team. To better reflect the professionalism and authority of the coach, a dedicated lanyard can be customized as the coach’s unique identity.

The lanyard is printed with the coach’s name, team slogan, pattern, and other elements to convey the team’s values, spiritual pursuits, and team culture. During training and competitions, the coach wears a lanyard, which not only allows him to access necessities such as whistles and identity cards at any time but also improves work efficiency.

The design elements on the custom lanyards also motivate the players to train harder and fight for the honor of the team.

By: @DBAFootball

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / NurPhoto