What’s Wrong with Manchester United’s Defense?

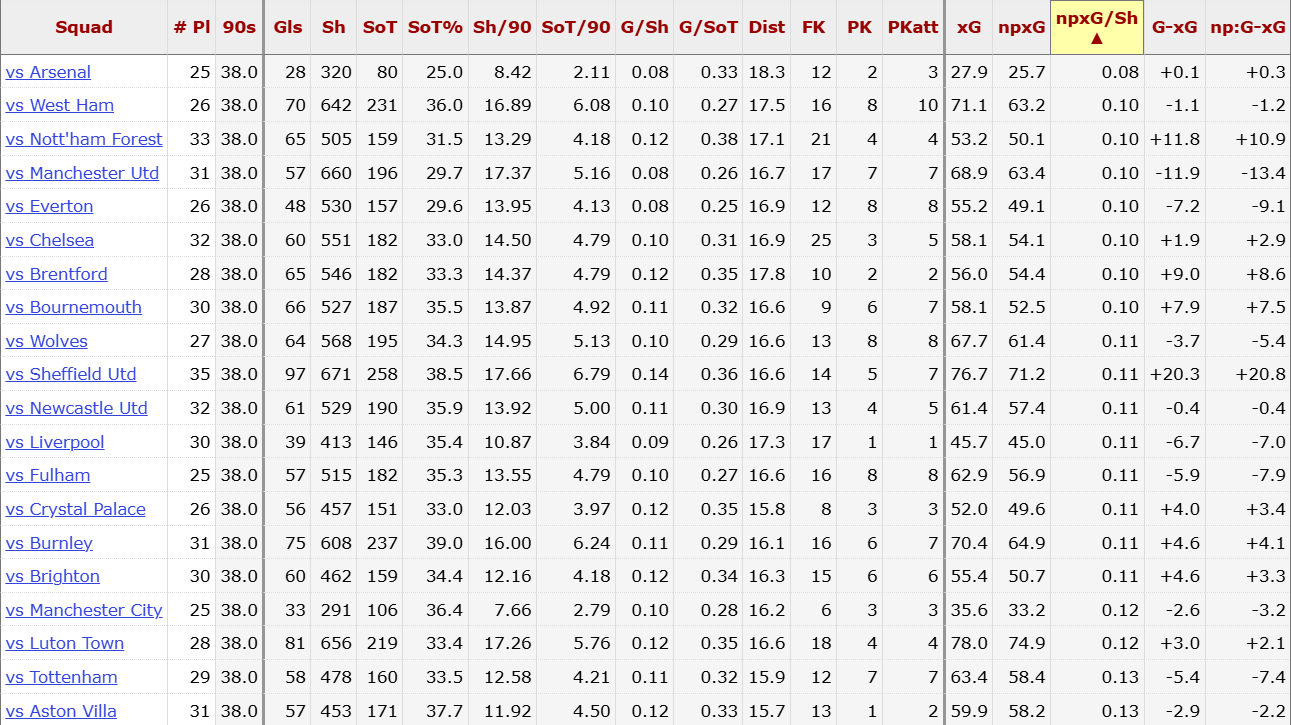

In the second half of the season, there was a lot of discussion about Manchester United’s defense in the media. In particular, there was talk about the number of shots that were allowed on Andre Onana’s goal. When we look at the raw numbers, it seems that Erik ten Hag’s team was struggling – only Sheffield United allowed their opponents to shoot more than Man United in Europe’s top five leagues.

This text is an attempt to dive deeper and understand the reasons behind these disappointing statistics. We will analyze the situations in which Manchester United’s opponents created the most dangerous chances.

Episode Evaluation Method

Each episode was given one of 20 labels, which can be grouped into 9 categories. The evaluation was done manually, so there may be human error in the data. All categories and labels are listed below.

- Passing attacks:

Pass – an attack with a pass into the field/penalty area

In-behind – a pass behind the defenders

Counter – passing through the defensive line

- Flank attacks:

Cross – high-flying flank attack

Low-cross – flank attack with medium/low height

Cutback – flank attack followed by a second tempo

- Transition phases:

Own – counterattack starting with a selection in our own half

Opponent – counterattack starting with a selection on the other team’s half

- Rebounding:

Rebound attack – shot after several rebounds

Rebound kick – 1-2 touch kick after the rebound

Discount – deliberate reset after a long/flank pass

Finishing – instant kick from the penalty area after saving

- Dribbles:

Isolation – displacement from the flank to the center of the lead

Dribbling – any other stroke situation

- Corners

- Set-pieces:

Free kick – kick after giving/drawing a free kick

Free kick – direct kick from a free kick

Out – kick after an out

- Long-range strikes:

Long-range strike – strike from outside the penalty area

- Penalty shootout

For analysis, data from United’s matches in the Premier League and Champions League was used, but some data was lost due to parsing issues with Whoscored.com. The final sample consisted of 717 shots. Each shot was given a data on the player who took it, xG (expected goals), the zone of the pass, and the shot was automatically assigned to each shot.

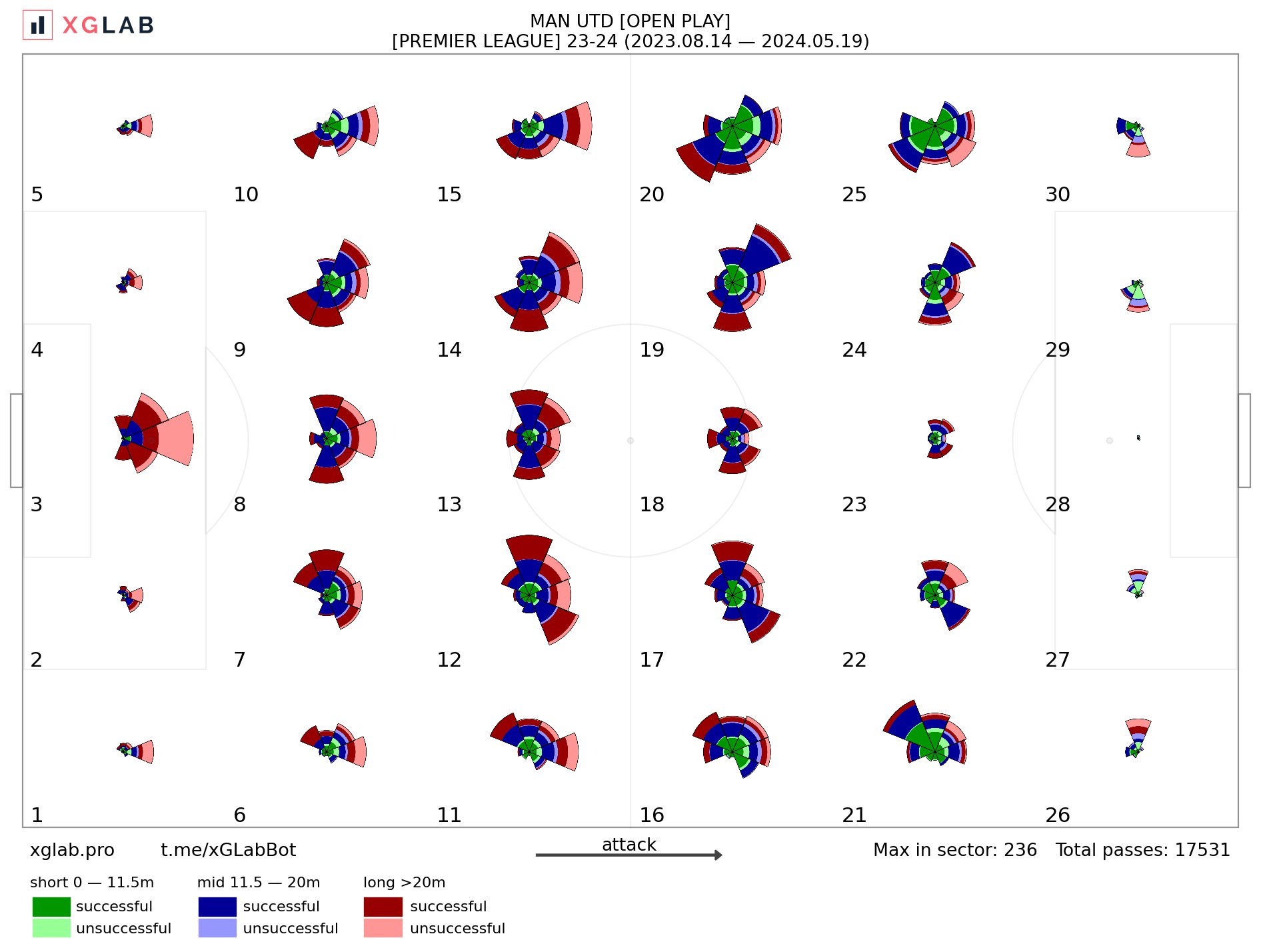

An example of how the field was marked by zones is shown in the image. A few times I will compare the figures of United’s opponents with United’s attack statistics, out of curiosity, and also with the statistics from another European championship. This will allow me to compare it with a larger dataset.

Passing Attacks

United’s opponents scored 14% of their goals after passing combinations. Of these, exactly one third was box entries after a short pass. Ten Hag’s team often played in a low block, so the opponents didn’t have many opportunities for through balls. The space behind the defenders’ backs appeared, for example, after unsuccessful pressing.

Bayern Munich were the best at catching United in the transition – the Germans scored two goals after through balls and in-behind passes. They scored more than 1.5 expected goals (xG). Leroy Sane hit the post and Mathys Tel scored the game-killing goal.

United’s rivals present the most danger from areas 23 and 27. This statistic aligns with personnel issues – in front of the penalty area, the team is struggling due to Casemiro’s poor form, and inside the penalty area they allow many opportunities from the LCB area, where Lisandro Martinez’s absence loomed large. United have conceded 10 goals in these situations, only after corners they concede more (11).

Erik ten Hag’s emphasis on a more direct style and focus on transition can be seen in United’s attacking statistics. About 7% of their shots come after passes behind the back – a percentage almost four times higher than their opponents’. Aston Villa and Luton have suffered most from Bruno and co’s vertical passing, with both opponents allowing three shots each. This is to be expected when Villa play with a bold, high-pressing style. Alejandro Garnacho, United’s fastest attacker, made 4 shots in these games.

Flank Attacks

Throughout the 2023/24 season, United was often criticized for its mediocre control of the area in front of the box during flank attacks, and this criticism is supported by the statistics. The percentage of shots allowed after flank passes for Ten Hag’s side is about 9.5%, most of these shots came after cutbacks.

Analyzing Manchester United’s Start to the 2023/24 Season Under Erik ten Hag

This is an unusual situation. In a larger sample of data from another European league from the 2023/2024 season – the number of goals after cutbacks is 4 times lower than after crosses. Of course, we should take into account the style of play in that league, but even then, this would not explain such a huge difference. Ten Hag’s team does not seem to do a good job protecting zone 23 when receiving passes from the side, and we need to look at Casemiro again here.

When the ball is near the edge of the field, Brazilian often rush into the penalty area to help their teammates in aerials in case of a cross. If instead, a pass is made back diagonally to the zone 23, Casemiro may not have enough time to switch positions, as his movements become less sharp, and the opponent’s player can easily receive the ball and score without much resistance.

The main issue for Manchester United’s defense is their inability to deal with cutbacks, particularly against opponents like Anthony Elanga from Nottingham Forest. In the first minute of the match, Elanga gave a pass to Nicolas Dominguez. Half an hour later, he made another similar pass to Ryan Yates. At the end of the game, he ran into the counterattack and helped Morgan Gibbs-White score.

United allowed the majority of shots after cutbacks, but the opponents created the most dangerous moments in front of Onana’s goal after low-crosses. 75% of the shots after low passes into the penalty area were applied almost directly from the goal zone, and the average xG was equal to an incredible 0.27.

At the beginning of the season, Ten Hag’s team had specific difficulties defending against these crosses – Wolverhampton and Brighton made 6 shots from low passes into the penalty area, with Danny Welbeck scoring one of them. If we look at flanking attacks as a whole, exactly half of all the opponent’s strike combinations came from zones 26 and 27.

Due to the constant injuries to Luke Shaw and Martinez, as well as the unavailability of Tyrell Malacia, Ten Hag was unable to build the necessary connections on the field, given the forced rotations in the positions of the left and left-central defenders. United had a central defender, a left-back, and a right-winger on the left side of the defense, with Casemiro and even Bruno Fernandes playing in the center.

Manchester United Must Now Decide Whether to Stick With Erik ten Hag or Sack Him

Dribbling

Strikes from this category have two main features: the first is the area of the field where the ball is passed from. United’s opponents make almost every fifth pass from the zone in front of the penalty area. A typical situation would look like this: one of their players drags the ball into area 23 and forces the central defender to attempt a tackle.

The central defender steps out of line and creates space behind him. However, the second CB often does not have enough time to cover his partner. An opponent’ s partner then runs into the empty space, receives the ball in the penalty area and shoots on Onana’s goal.

The second feature of these strikes is that they often happen during transition phases. United has not developed a strong counter-pressure, and their players enter the defensive phase after a loss without a clear plan. This often gives the opposing team an advantage when they switch from defense to offense. The attacking group of United is stuck in a high position and responds slowly to the loss.

The Curious Case of Scott McTominay: Assessing His Future at Manchester United

The defensive line and defensive midfielder do not press hard enough, as they are afraid of to get caught by an in-behind through ball. A gap in the middle of the field occurs, which allows opposing players to create a lot of 1v1 situations on space. Due to Casemiro’s poor performance and Sofyan Amrabat’s lack of sharpness, these situations often lead to successful take-ons and shots afterwards.

The match against Wolverhampton in the first round was a clear example. Pedro Neto and Matheus Cunha exploited the space on the field, while Onana was fortunate not to concede in his debut game in the Premier League.

The third feature is the impact zone. Less than 15% of shots after dribbling come from the center of the penalty area. For other categories, this figure does not fall below 26%. This is due to the fact that the closer a player is to the goal, the more difficult it is to maintain possession of the ball.

When taking a pass on the edge of the penalty area, the opposing winger attempts to beat the defensive midfielder and immediately shoot after breaking past them. Given the issues on the left side of the defense, as well as the strong 1-on-1 situation between Aaron Wan-Bissaka and Andre Onana, it is surprising that opponents of United hit Onana’s goal more frequently after isolating against the right defender of Ten Hag’s team.

Second Balls

United’s opponents score about 16% of their shots from second balls. This is the second most common category, considering ball-in-play attempts. There is also a strong correlation between second ball shots and other categories such as longshots, crosses, and corner shots. All these situations are united by the defensive strategy of United.

One of Erik ten Hag’s defensive ideas is to allow opponents to take a lot of shots, but to reduce their quality. United’s xG/shot ratio is 0.1, which is the second best in the Premier League after Arsenal. This statistic is due to the large number of players positioned between the shooter and goal for United.

Photo: FBRef.com

Regarding corners, the explanation is simple – United leaves 9 players in the penalty area, and 5-6 opponents are added to that. Any shot after a rebound is more likely to be blocked rather than reaching Onana. When United’s defensive players are pressed, Casemiro often finds himself in the penalty area. He helps the centre-backs with aerials, but if the ball bounces into area 23 after a cross, an opponent’s player can hit it without resistance. Casemiro may not have time to tackle him, but he acts as an extra blocker.

Everton was the most efficient team to exploit United’s weaknesses. Sean Dyche’s side has excellent movement in the rebound area after long passes and crosses, in two games against Ten Hag’s team, they took 14 shots on target with the second tempo. Dwight McNeil and Abdoulaye Doucoure stand out, with the Englishman taking 5 shots after rebounds and the Frenchman hitting three times.

Transitional Phases

Last summer, Erik ten Hag stated that his goal for Manchester United was to become the best team in the world at playing in transition phases. When the team switched to attack, they looked good – Bruno Fernandes found Garnacho running behind with precise passes, and the Argentinian scored three goals.

However, when it came to defensive transitions, things were more challenging. Three weaknesses of United made it especially dangerous: poorly executed counter-pressure and the inability of central defenders to play a high line, which allowed a large number of opponents to start attacks from the other half of the field.

The worst match in this regard was against Chelsea in West London. United allowed three shots from within the penalty area after losing possession in the other half of the pitch, with a total xG of 1.39.

The randomness and lack of ideas in United’s build-up, except for Dalot’s slides in the middle, leads to a large number of possessions lost in their half. After losing possession in their own area, United players find themselves in difficult positions. The spaces between them are not optimal, and attempts to immediately regain possession only lead to the creation of new empty spaces.

These problems are particularly evident against aggressively pressing opponents like Bournemouth or Crystal Palace under the guidance of Oliver Glasner. Dominic Solanke scored one goal and hit the post, Michael Olise also found the net, and had two more dangerous shots, which were saved by Onana.

Additional factors that contribute to Manchester United’s defensive weakness include the individual weaknesses of the defenders in possession and personnel issues within the club. The central defenders are skilled at making long passes – Harry Maguire’s diagonal passes are particularly impressive – but under pressure, they often opt for a simple pass to a teammate or a safe long ball option. Wan-Bissaka behaves similarly.

The ongoing absences of Shaw and Martinez also play a role. When the Argentine is on the pitch, the team is more relaxed when launching attacks. Martinez’s movement is competent, he communicates well with his teammates, understands when to speed up the attack and when to maintain possession, has an accurate first pass, and is not afraid to take risks with the development of the play.

Other Categories

Long-range shots – United allowed their opponents to take 115 shots from afar on Onana’s goal, but none of them were scored.

Free kicks – a text analyzing United’s performance in both attack and defense will be released before the 24/25 season starts.

Corners – a text analyzing United’s corner play in the second half of the 23/24 season will be published in June.

Penalties – the sample size of penalties is too small for analysis and is therefore not relevant.

By: @normalnik131

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / Reuters / Carl Recine