What Is Beautiful Football?

What is beautiful football?

We always hear the phrase “beautiful football” discussed in podcasts, pubs, and dinner tables. Some people spend hours on social media fighting about the very meaning those two words. Some managers lose their jobs for not getting their teams to play beautiful football. Some coaches lose their players because they’re sick of playing ugly football all the time. Nonetheless, nobody seems to really have a solid answer on what beautiful football constitutes-can anyone play beautiful football, or are there certain wastelands where previous managers have salted the pitches, and the only things that can grow in the stadium are weeds of bland long-ball systems?

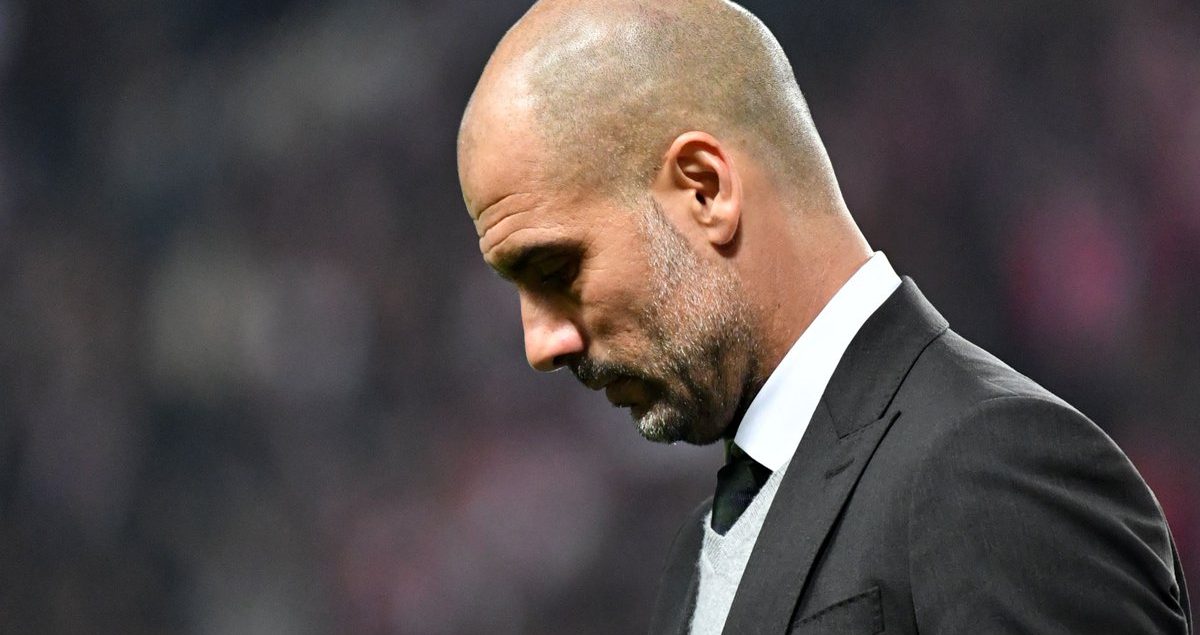

These past few days, we may have seen two losses for beautiful football. On Tuesday, Jorge Sampaoli’s possession-loving Sevilla FC exited the UEFA Champions League after Craig Shakespeare’s “shamelessly-in-love-with-counters” Leicester City FC achieved a 2-0 remontada in the King Power Stadium. The day after, Leonardo Jardim’s Monaco knocked out Pep Guardiola’s Manchester City with another 3-1 remontada in the Stade Louis II. In Jardim’s first season at Monaco, Les Monégasques advanced to the Champions League quarter-finals with a defensively-organized setup, only to be defeated with a dubious penalty by the eventual runner-ups, Juventus. On the other hand, Guardiola rose to fame with “tiki-taka” at Barcelona, a concept of one-touch give-and-gos and a heavy possession-oriented system.

Despite their idiosyncratic reputations, Sampaoli and Guardiola share several distinct traits. They both hail from Spanish-speaking countries, they are both disciples of Spanish manager Juanma Lillo, and they tend to split football fans in half: one side that religiously studies them as visionary godsends, and the other that writes them off as hipster fools who need to “get back to basics.”

In reality, they have both managed to consistently get their teams playing certain styles of football in short spans of time, who have adapted to different game plans for different scenarios, and who have racked up respectable trophy hauls in their relatively short careers. And they both got it terribly wrong this week.

If Manchester City were supposed to be a team focused on calculated possession and strict positional play, they certainly didn’t look like it on Wednesday. Too many times, Monaco were able to retain possession for long periods in City’s own half, to link up without trouble near Willy Caballero’s area, to isolate City’s front three from its midfield. Pep Guardiola benched his de facto “mediocentro” Yaya Touré, and didn’t bring him on for the entire match. Instead, he stuck with his two veteran full backs, Gaël Clichy and Bacary Sagna, with his other left back, Aleksandr Kolarov, partnering John Stones, who, at 22, started for just the second time in the Champions League knockout rounds.

Not once did Pep change to a three-man or five-man backline, put on a hug-the-touchline winger to add width, or sub on a tricky 1v1 player to help break down Monaco’s defensive block. With 10 minutes left, he subbed Clichy off for his backup center forward Kelechi Iheanacho, which seemed like nothing more than what you do when you’re losing 1-0 on FIFA with the clock ticking down. There was no real Plan B, it was more “let’s bring on another striker and see if he can get a flick on by the near post.”

City found themselves in a near-identical situation in the first leg last month. Trailing by a goal at halftime, Guardiola had to devise a solution. With Yaya Touré swarmed by Monaco’s two strikers, and Jardim’s narrow press limiting City’s build-up, Pep needed to find the remedy before Monaco came away with a win in the Etihad. Pep switched from a 2-3-5 in possession to a 3-2-5, and a 4-3-3 off-the-ball shape to a 3-4-3 out of possession. This allowed more fluidity in the first phase of build-up, drawing Fabinho and Tiemouyé Bakayoko wide with their runs and freeing up space in the middle for Sergio Agüero to drop back, receive vertical passes from the center backs and play lay-off passes to the wingers and Kevin De Bruyne.

It worked, and City won the game 5-3. Maybe it was a “hipster approach,” but it was necessary for City to win.

Last year, Pep’s Bayern Munich found themselves two goals down at halftime against Juventus in the second leg of the Round of 16, facing the same structural problems as City this year. Juve’s gung-ho pressing limited Bayern’s build-up, even stifling Manuel Neuer’s influence, who is normally used as an emergency passing option. Due to Juventus’ immaculate pressing, Bayern found themselves unable to link up in dangerous central possessions, and by halftime, they needed to score two goals to send the tie into extra time.

Pep needed to use his substitutions wisely. He took off Mehdi Benatia for Juan Bernat, moving David Alaba to center back and adding extra width on the left side, while also taking Xabi Alonso off, moving Arturo Vidal to a sole regista role, for his hug-the-touchline winger Kingsley Coman.

Bayern were able to turn around the deficit, and eventually send Juventus packing, due to three main tactical changes: vigorous pressing of Juve’s center backs by the two strikers, overloading of central areas, and crossing.

Crossing? But I thought that was the devil’s last resort, where tactical nitwits send their behemoth forwards to latch onto long balls, the lazy solution, the cop-out, the red light district of the footballing oasis?

In Guardiola’s final season in Bavaria, the signings of two direct wingers in Douglas Costa and Kinglsey Coman allowed Bayern to add another dimension to their game: crossing. Robert Lewandowski is one of the best in the world, if not the best, in latching onto a low cross or winning an aerial duel. This strategy was vital to Bayern’s play, and it added one more solution to a possible tactical threat for the Bavarians.

Being the best doesn’t mean having one really good system. It means knowing different answers to different questions: If your opponent switches from a 4-3-3 with inverted fullbacks to a 4-4-2 with pressing triggers, what do you do? If your opponent moves from a 3-4-3 to a 4-5-1 out of possession, who should you sub on to break down the new formation?

All of this might sound like Football Manager gibberish, but the elite managers don’t dedicate their lives to studying the game because they like seeing beautiful football; they do it because they’re obsessed with winning. As Sun Tzu argues in The Art Of War, if you only know yourself, you may win or lose, if you know your enemies and know yourself, you will not be put at risk even in a hundred battles.

Leicester’s title victory was considered refreshing for many reasons. First of all, it was a rejection of the newfound “superclubs,” teams such as Manchester City and Chelsea who had ascended to the Premier League elite after being bought by foreign businessmen. Second of all, it was an underdog story; many starters, from N’Golo Kanté to Jamie Vardy had been playing in the inferior leagues of French and English football, and were very much unknown before the 2015-16 season. Finally, it was a victory for “ugly football.” Leicester played a 4-4-2, considered to be the most basic defensive system there is. None of Leicester’s back four were considered “ball-playing defenders.” Their fullbacks weren’t skilled at playing one-twos or dribbling out of pressure, Jamie Vardy isn’t a false 9, Shinji Okazaki isn’t a raumdeuter, and let’s just say, a double pivot of Danny Drinkwater and N’Golo Kanté isn’t exactly the second coming of Xavi-Iniesta.

But who cares? They got the job done. They entered the season with a set of tactics and attributes commonly founded in relegation battlers, and they ended up winning the Premier League. In an era of “oversaturation,” with an abundance of money, stars, and tactics, this was seen as a return to the good old days.

Leicester City eliminated Sevilla because they were stricter in their adherence to Shakespeare’s game plan than Sevilla was to Sampaoli’s. Furthermore, they tricked Sevilla into panicking, into trying to play the Leicester way, with rushed possession and high crosses. Sevilla thought they could beat Leicester in their own game. That’s like Verne Troyer challenging Lebron James to a slam dunk contest.

Nonetheless, to not attribute Leicester’s stunning victory to Craig Shakespeare’s tactical genius would not only be idiotic, it would be downright disrespectful. Leicester relied on pressing triggers and coordinated off-the-ball movements against Sevilla; they won because Shakespeare did his homework.

Arguably the two best managers in the world will not play another match in Europe this season, and it’s St. Patrick’s Day. Still, big-name coaches do not have a monopoly on genius. The likes of Zidane, Luis Enrique and Craig Shakespeare are in the quarterfinals because they did their homework, outplayed their opponents and earned a place in the last eight. These styles of play may not be the prettiest, but the best managers study and adapt to every style of play that can gain three points.

I wrote this essay when I told my mother that Sevilla’s loss was considered a loss for beautiful football, and when she asked me, “What does beautiful football mean?” I tried to explain to her, until I realized that, I myself did not know. Beautiful football stretches across mountains and seas, in different languages and different epochs, and it represents the tapestry that is the tactical side of football. Managers don’t get paid to play aesthetically-pleasing tiki-taka every week, they get paid to win. Thus, beautiful football pertains to the different manners in which a manager can win a football match.

So, were the results of this week really a loss for beautiful football? Do we have to demean a story in which relegation fighters and a new, unrenowned manager qualify for the quarter-finals of the UEFA Champions League? Is it necessary to bad-mouth a tale of youthful exuberance (Monaco’s average age was 24), where a bunch of kids send a two-time Champions League-winning manager packing from the Round Of 16 for the first time in his career?

Football is a game of decisions. If Pep decided to buy more defenders in the previous transfer window, Manchester City might have advanced. If Sampaoli started Mariano and Clement Lenglet, perhaps they’d have buried the Premier League champions. If Ahmed Mahrez didn’t illegally escape to Paris to get a pacemaker installed, we wouldn’t have Riyad Mahrez, and we wouldn’t have the greatest story in Premier League history.

Football is beautiful because of the graceful wingers, because of the last-ditch slide tackles, and the vertical passes that break the lines. But it’s also beautiful because of the stories it tells. It’s beautiful because anyone with a strong belief and 11 players who believe in his vision can win against the most unlikely of circumstances, because a teenager from the reserves can crush the hearts of millions, and because of the ties that bind us together.

Photo Credit: Getty

By: @ZCalcio