The False Dawn of West Ham United

“I’m forever blowing bubbles, Pretty bubbles in the air, They fly so high, Nearly reach the sky, And like my dreams, they fade and die, Fortune’s always hiding, I’ve looked everywhere…”

West Ham’s long-cherished matchday chant is a bittersweet ode to the highs and lows of relentless, undying hope. In recent years, the song has never been more relevant to the East London outfit – a swathe of mismanagement from the-top down has left fans desperately searching for any sign of the success they were promised a decade ago. As the old saying goes, it’s the hope that kills you.

In 2019, Forbes ranked the Hammers as the 17th richest club in the world. In 2018, they ranked 14th – more than the likes of Schalke 04, Leicester City and, most shockingly, both AC and Inter Milan. In 2012, they acquired a 99-year lease of the London (then Olympic) Stadium – the fourth-largest stadium in the Premier League, which chalked up an average attendance of 58,349 in 2018/19.

Photo: Getty

Across recent transfer windows, West Ham have been able to splash out on some of Europe’s highest-rated players, with their wage bill comparable to that of Leicester City and Tottenham Hotspur. The infrastructure for a successful club is in place. But despite all of the above, the Hammers have found themselves lingering in the Premier League’s bottom half for all but one season since moving away from their beloved Boleyn Ground.

This poor record has been further marred by off-the-pitch fracas, often giving the impression of a circus sideshow instead of a professional football club. With West Ham currently fighting to stay in England’s top division, many are wondering just how it has gone so wrong in Stratford this year, following a respectable 9th-placed finish in 2018/19.

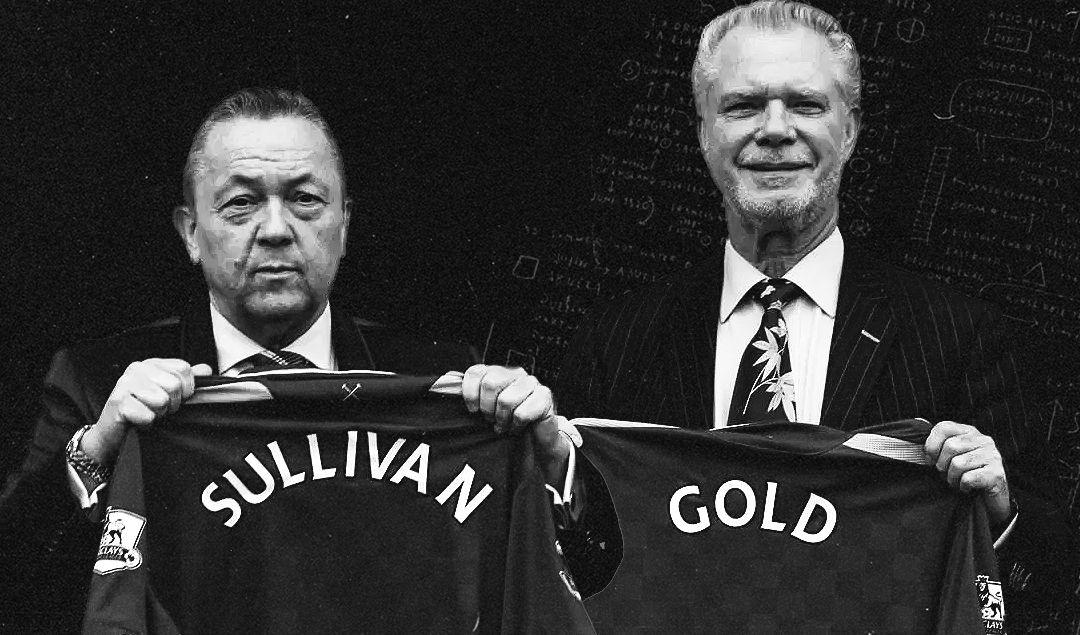

Much of West Ham’s struggle can be attributed to a lack of long-term vision from the club’s ownership. Prior to the club’s London Stadium transfer, the club’s primary shareholders, David Gold and David Sullivan, had frequently expressed their desire to make West Ham a European powerhouse in the seasons following the eventual move in 2016.

West Ham’s final season at the Boleyn had been hugely successful, with the club securing a 7th placed finish under club legend Slaven Bilić. This outlier season can be attributed to the extraordinary performances of now-controversial Dimitri Payet, as well as squad morale being at an all-time high in anticipation of the new stadium.

The cracks in West Ham’s management started to show at the beginning of the 2016/17 season. It is unknown the extent of Bilić’s role in West Ham’s recruitment, but there is enough evidence to suggest that a large portion of transfer dealings were conducted by Sullivan, whose background in football seems almost non-existent amongst a detailed business history of tabloid newspapers and sex shops.

A lack of coherent club vision between Bilić and Sullivan led to a series of financially-draining ‘marquee signings’ from 2016 to 2018, with no clear rhyme or reason as to how these expensive individuals would operate as a team.

Above is an excerpt from Transfermarkt detailing West Ham’s most high-profile transfers from the 2017/18 season. Of the six senior players (Sead Hakšabanović spent most of his West Ham tenure in the U-23s), four were either at or past their footballing peak. This gave little potential for coaching and improvement, and they were expected to adapt immediately to Bilić’s often-unclear playing style.

They were ‘big names’ acquired with little systemic purpose. This mish-mash of signings did little to help West Ham’s league performance, and following an especially poor run in November 2017, Bilić was sacked and replaced by the rather uninspiring David Moyes.

A glaring example of West Ham’s poor recruitment is Mexico legend Javier Hernández, signed in summer 2017. ‘Chicharito’, one of modern football’s last pure goal poachers, was 29 and past his prime upon joining the Hammers, having spent the last two seasons at Bayer Leverkusen.

During his playing days at Manchester United, Hernández had adopted the role of a ‘super sub’, capable of nicking goals from tired defences late in the game. Upon joining the Hammers, he was shoe-horned into a lone striker role, which he simply did not possess the physical acumen or link-up intelligence for.

Photo: West Ham United via Getty

Following Bilić’s dismissal, he fell out of favour with Moyes, and was once again relegated to a bench player. After scoring 16 goals in 55 league appearances, he was sold to Sevilla at the start of the 2019/20 season for less than half his original fee. Chicharito earned in excess of £140,000 per week over two years at the London Stadium, despite spending less than a single season as a regular starter.

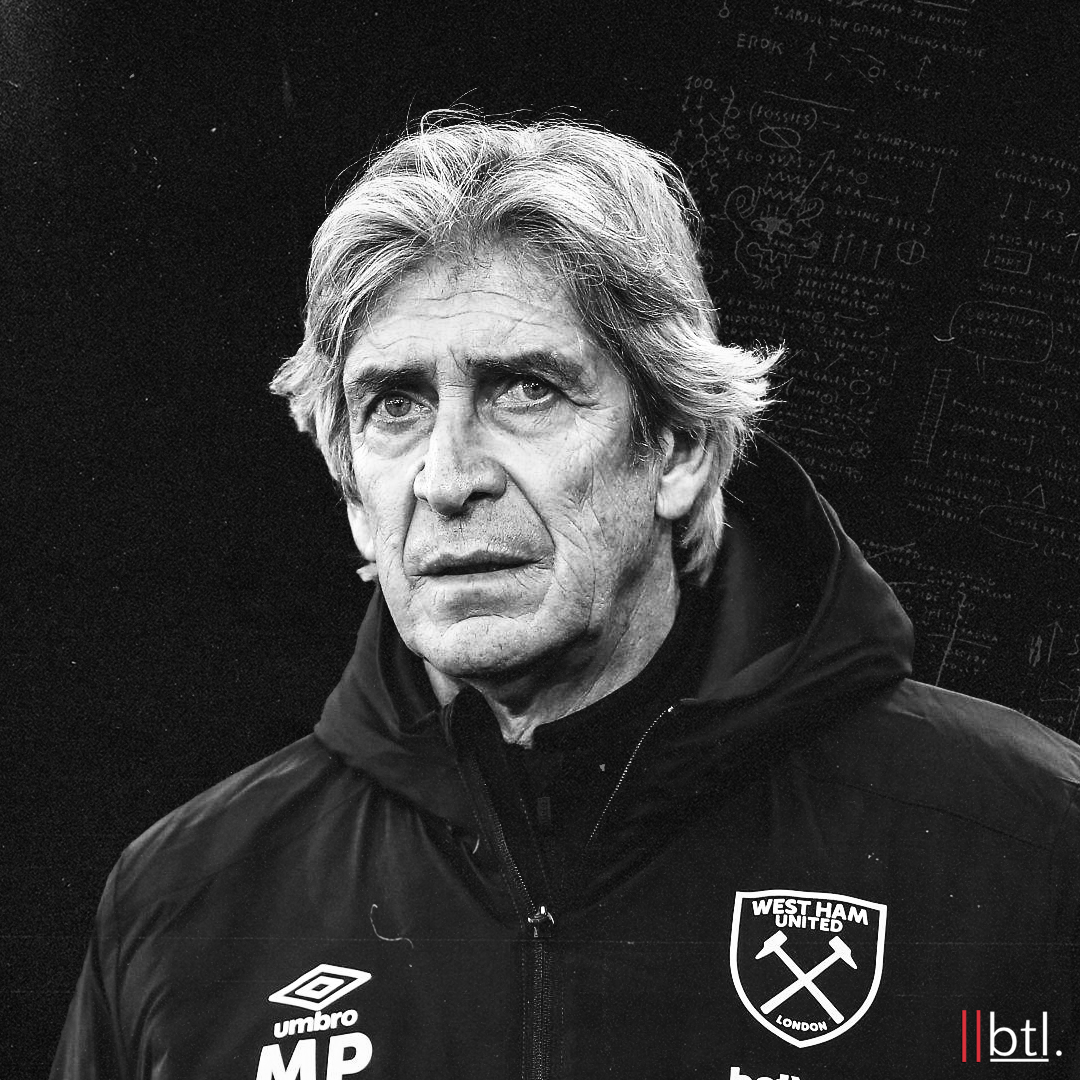

Despite a turbulent run at the tail-end of 2017/18, Moyes kept the Hammers afloat, and following the expiry of his short-term contract, a glimmer of hope surfaced. In the summer of 2018, the club announced the appointment of Manuel Pellegrini on a £10m-a-year contract.

Pellegrini was joined by sporting director Mario Husillos, who has previously worked with Pellegrini at Malaga during the 2012/13 La Liga season. After several directionless years, it finally appeared as if West Ham were going to turn a corner and kick- start a sustainable footballing project under Pellegrini’s attack-minded leadership.

Pellegrini and Husillos’s first transfer window was one of mixed successes. Felipe Anderson, Issa Diop and Ryan Fredericks had all become accustomed to free-flowing, attacking football at their previous clubs and were signed prior to their peak years. All three shone in the 2018/19 season. Additionally, experienced stopper Łukasz Fabiański proved to be a revelation between the sticks, collecting the club’s Hammer Of The Year in his first season at the club.

However, there were also plenty of downsides. The signings of Carlos Sánchez and Lucas Pérez were cheap, underwhelming panic buys that could easily have been avoided with appropriate organisation and planning.

In addition, Jack Wilshere and Andriy Yarmolenko were largely unnecessary signings; the pair were both at their peak, had taken a step down from larger clubs and had known injury concerns prior to signing. To put it bluntly, the gamble did not pay off – according to various sources, both earn in excess of £100,000 per week at West Ham despite having spent most of their time on the injury table.

There was little attempt made to strengthen positions of weakness, namely the left-back position, and this owes in part to inflated wages paid out in unnecessary areas. It never felt as if these players were signed as a result of a cohesive, well-ingrained scouting network – a feeling that became more justified when it was revealed Pellegrini and Husillos had appointed close friends and family as part of West Ham’s recruitment team during their tenure.

Expensive deals involving player agents further tarnished West Ham’s spending record. A recent Football London article revealed that West Ham had paid out £13,167,647 in agent fees over the past year – more than the likes of Tottenham Hotspur and Wolverhampton Wanderers. This is an extortionate amount needed to lure players to the club – many of whom have arguably failed to justify their lofty price tags.

Nevertheless, as mentioned earlier Pellegrini guided the Hammers to a top-half finish, leaving smiles all round on the East End. The following summer, Hammers fans were itching to see West Ham improve in the new season, with many pundits tipping the side for a Europa League push.

Pellegrini continued to build, with £22 million-rated playmaker Pablo Fornals signing from Villarreal, followed by the arrival of highly-coveted striker Sébastian Haller from Eintracht Frankfurt.

Photo: West Ham United via Getty

However, whilst fans were overjoyed at their flashy new signings, a player exodus was taking place under their noses. Four senior strikers were sold in the summer, in addition to Pedro Obiang, West Ham’s only true box-to-box midfielder. Neither positions were appropriately replenished.

West Ham are no strangers to an injury crisis and, following a bright start to the 2019/20 season, their lack of squad depth became astonishingly apparent. The most damning of these injuries was star goalkeeper Fabiański, who missed 14 games between September and January. Backup keeper Roberto, a Husillos summer signing, was simply not of a top-level standard, and cost the Hammers valuable points with a series of amateurish mistakes.

Obviously, it is not fair to place the blame on a single player for the Hammers’ poor winter run – the club also suffered from lack of depth in several key areas, which drastically affected how well the squad executed Pellegrini’s footballing vision.

Fan patience waned thin, results tanked, and Pellegrini was relieved of his managerial duties in December 2019, with the club sitting 17th in the table.

David Moyes was swiftly re- appointed for a second stint at the wheel, and so far his attempts to steer West Ham from danger have been sub-standard to say the least, with the Hammers picking up 8 points from a possible 36 since the Scot’s arrival.

As of the time of writing, they sit level on points with Aston Villa and Bournemouth, only just escaping the relegation places on goal difference. Their Premier League fate is still very much up in air, however regardless of what happens, there is little argument to support Gold and Sullivan’s West Ham ‘project’ as being a successful one.

So, what can West Ham do to improve? A sale of the club would no doubt delight the vast majority of Hammers fans, however it does not appear to be on the horizon any time soon. Realistically, there needs to be an overhaul from top to bottom.

A good place to start would be the appointment of a long-term director of football – a footballing mind with a clear, transparent playing philosophy. It is imperative that the owners and director of football are in mutual agreement over the club’s vision, and that transfer dealings are conducted by the director and the director only – no more expensive Sullivan signings.

The appointed director should choose the manager and not vice-versa; in summer 2018 Pellegrini essentially lobbied to appoint his close friend Husillos, who, in reality, had not enjoyed much success as sporting director of Málaga – the club was relegated in 2018 after several key players were sold and not replaced appropriately.

Photo: West Ham United via Getty

A good example of this approach is Everton, who have turned a corner under the vision of sporting director Marcel Brands and look poised for an exciting season ahead under the reputable Carlo Ancelotti. Despite losing the likes of Jean-Philippe Gbamin and André Gomes to long-term injuries, the Toffees have braved the storm and currently sit 12th — 14 points clear of the relegation zone.

A club of West Ham’s wealth should also invest plenty of resources into developing a world- class scouting network under the supervision of the director – they need to start searching for younger players with greater upsides and resale value.

Despite being the target of much criticism, Moyes has had the right idea with his winter signings – the additions of Tomáš Souček and Jarrod Bowen in January have both proved beneficial to the club’s performances and look very comfortable playing at a Premier League level.

The mess at West Ham is a result of years of negligence and will not be rectified over a single transfer window. It may even take a relegation (or worse) before any real change is made, but the issue is simple – West Ham are a club behind the times. Gone is the Premier League era of big-money individuals – the importance of singular brilliance has greatly diminished in favour of a well-drilled system, which the Hammers are yet to develop.

It’s been 40 years since West Ham’s last trophy — an FA Cup victory over Terry Neill’s Arsenal. They have never had a better opportunity to put their resources to good use and finally give the East End faithful something to cheer about. No matter how the club may fare under current ownership, the spirit of West Ham United is well and truly alive amongst fans far and wide, as it has been for generations – and where there’s life, there’s hope.

By: Charlie Jewers

Featured Image: @GabFoligno