Why the 4-4-2 Is the Go-To Defensive Shape

“Great defensive play is mostly organisational and positional in the modern game,” argued Carlo Ancelotti in his 2016 autobiography Quiet Leadership: Winning Hearts, Minds and Matches.

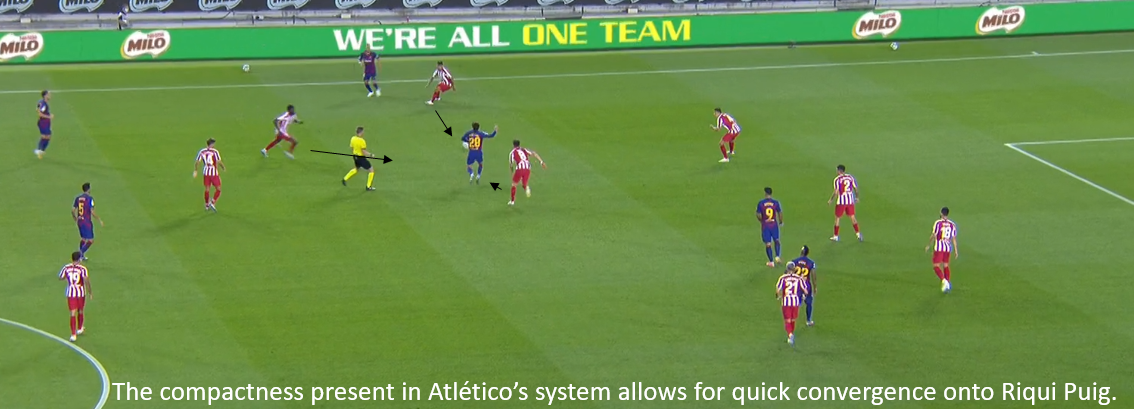

Perhaps the most frequent gesture that comes from a manager on the touchline is a compressing of the hands to signal to a team to remain more compact. Compactness is crucial to understanding football because it relates to the controlling of space and subsequently where the opponent can play through with ease, and thus where they are more likely to attack down.

Football is a game of space; players require it to receive the ball and attack into. Where the space lies influences the players’s decision-making, as they must constantly take into account the pressing and high tempo demands of the modern game before making a decision whether to pass, dribble, or shoot.

Compactness should be conceptualised in two ways: the distance in between lines vertically and the distance in between the lines horizontally. Lacking compactness can result in disastrous consequences, as opponents can gain territory quickly and mount goalscoring opportunities. To a degree, the theory of compactness would suggest that packing eleven players around a small area, i.e. the box, is not a successful defensive strategy.

The fundamental component of defending is coverage of space, with compactness only being an element, albeit a significant one as it pertains to space in between the lines. Therefore, a conundrum arises as to how to reduce the size of available playing area in defence as to ensure compactness while maintaining sufficient coverage of the pitch.

A frequent solution to this conundrum has been the 4-4-2 for three fundamental reasons:

1) Narrow wide players allow for central compactness.

2) Two players down the flanks and a shuttling midfield can help maintain horizontal compactness.

3) Central compression can be achieved through the two forwards and a zonal defence.

The defending team wants to make the pitch as small as possible and force the opponent into tight spaces where players can quickly press and force a turnover. The easiest way to reduce the size of the pitch is to funnel the opposition out wide, where potential passing options are restricted both in quantity and in scope.

A central player has a 360° angle of passing options compared to wide players who have their 180° angle cut off instantly by touchline. This explains why the phrase ‘touchline press’ is embedding itself within football’s vernacular, which is where the pressing intensity of a side increases substantially when a wide player receives the ball.

The 4-4-2 is effective at preventing central and half-space infiltration as the players remain protected throughout because of the central compactness provided by the narrow midfielders and forwards. Thus, they force the opponent to play through the flanks.

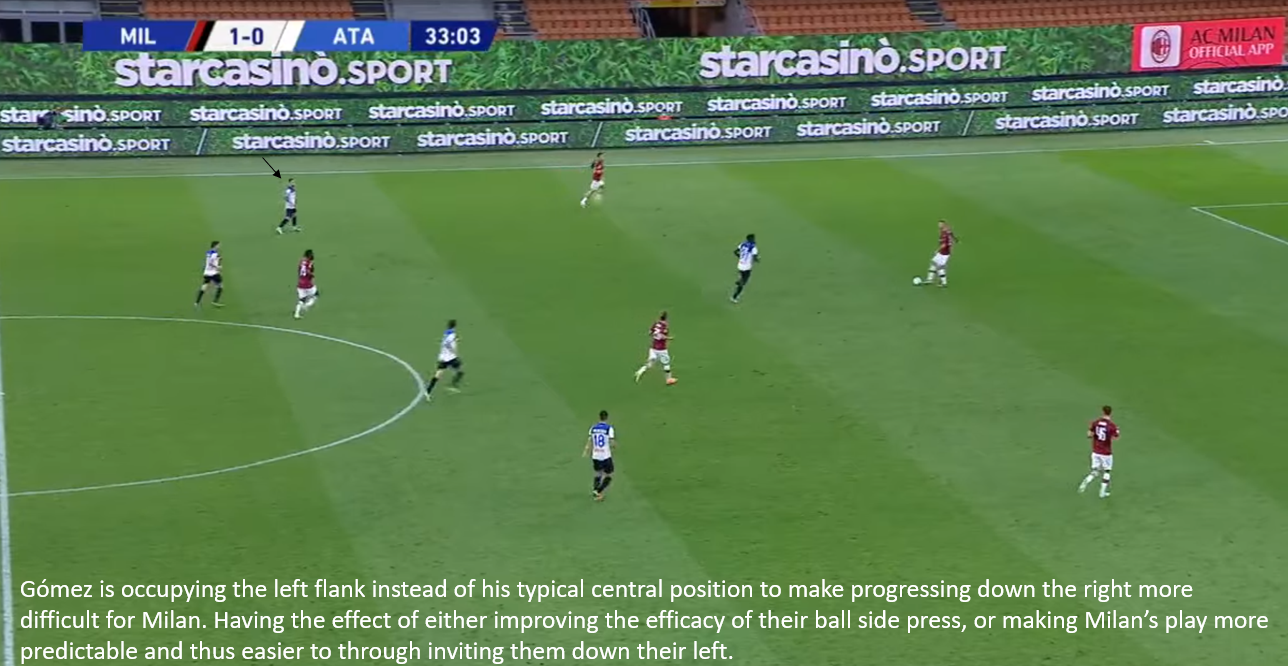

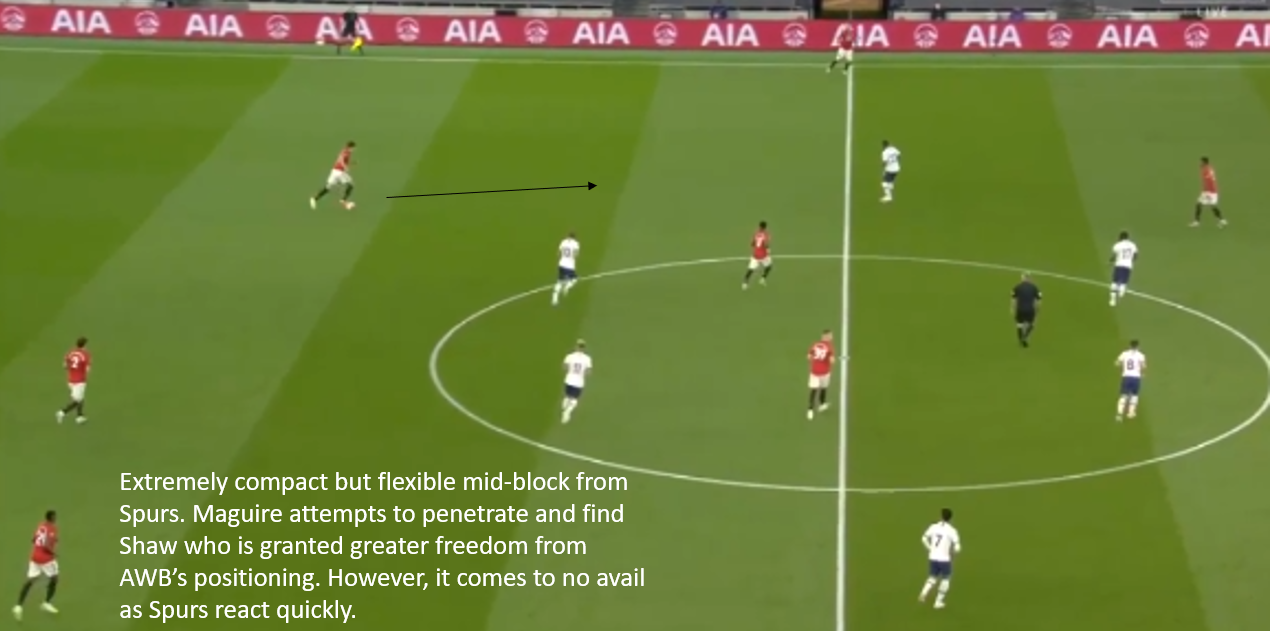

In this formation, the narrow central four simultaneously congest the middle of the pitch while also providing the potential to overload the opponent out wide due to having two dedicated players on the flank, with the other players subsequently shuttling over.

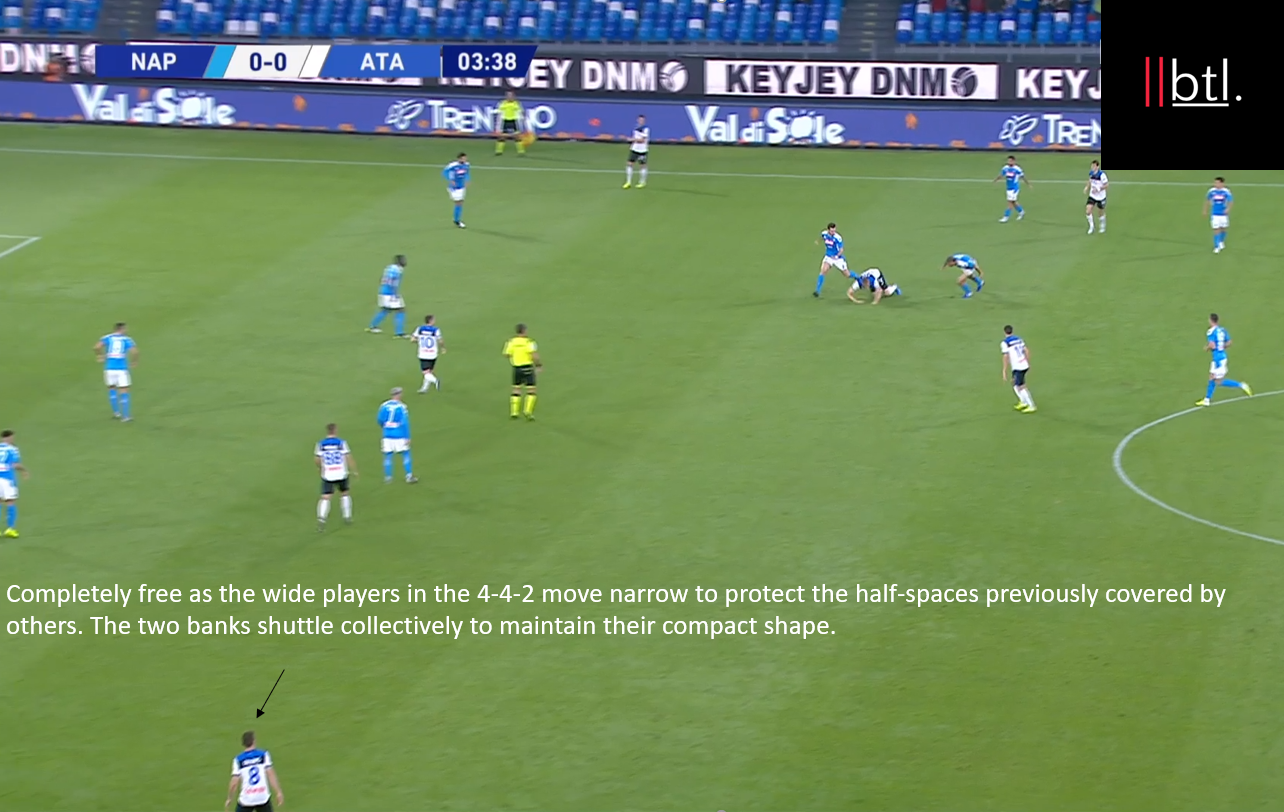

Shuttling is another crucial concept to understand when discussing the effectiveness of a 4-4-2. It is the collective movement of a team, typically towards the ball side with the intended purpose of reducing the size of the playing area, which consequently leaves another flank open.

This strategy is open to exploitation by technically and tactically proficient sides such as Maurizio Sarri’s Napoli who would frequently attack by baiting the opponent to shuttle to one side. They would often build play with short passing combinations on the left side, before subsequently switching it to José Callejón in space on the right flank.

However, axiomatic to the success of a shuttle is the closing down of passing options and the pressing of the ball which make it extremely difficult to play an accurate cross-field ball.

A ubiquitous maxim in football is that if you are being overrun in one area, you must be overrunning the opponent in another as there is a numerical parity of 11 vs 11.

Shuttling seeks to overrun the opponent defensively in all areas and resolve the compactness/coverage conundrum by leaving wide spaces open in central possession to remain horizontally compact, while also maintaining the potential to quickly move across once possession has been shifted out wide.

While there are disadvantages to this approach, it is far less risky to overcommit defensively than it is to overcommit offensively which often results in spaces being effectively covered.

In essence, the 4-4-2 is a shape suitable for shuttling, as the presence of two wide players on either flank accentuates the advantages through quick engagements, whilst also minimising the deficiencies as the two players on the other flank can adapt to a potential switch, engaging in individual duels while the rest of the team shuttles across to support.

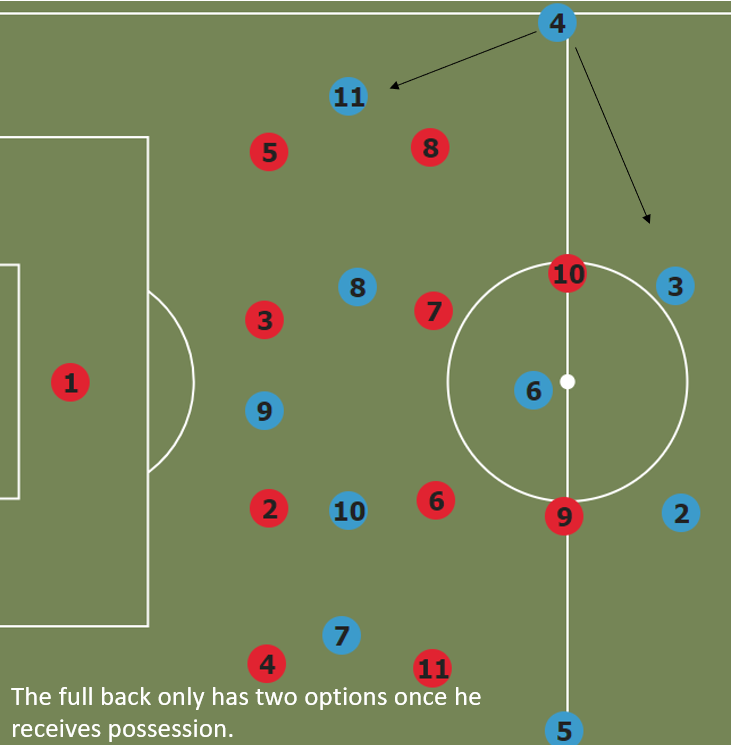

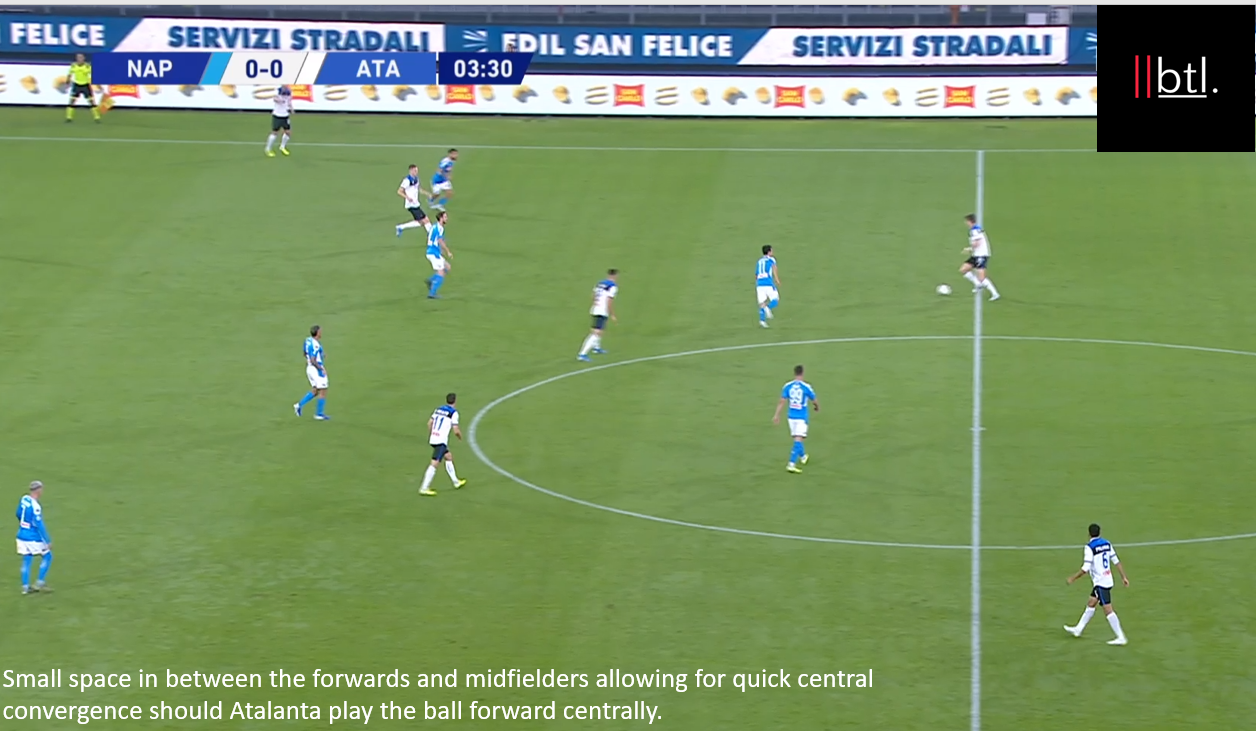

In recent years, we’ve seen several pragmatic sides such as Diego Simeone’s Atlético Madrid and José Bordalás’s Getafe use a 4-4-2 to remain compact and break on the counter. These teams often have their strikers drop deep in order remain vertically compact and to crowd the opposing defensive midfielder (or double pivot), thus forcing the opponent into holding defensive possession with their centre backs, should they choose to keep possession central.

This vertical compactness congests the midfield and forces play down the flanks, thereby allowing the central player receiving possession in the second line to be quickly closed down from four different angles.

In doing so, they ensure that the only safe progressive pass is to the full back, who will be forced to dribble out of pressure due to the strikers remaining vigilant to the opposing defensive midfielder’s zone, thus cutting off that passing option as well.

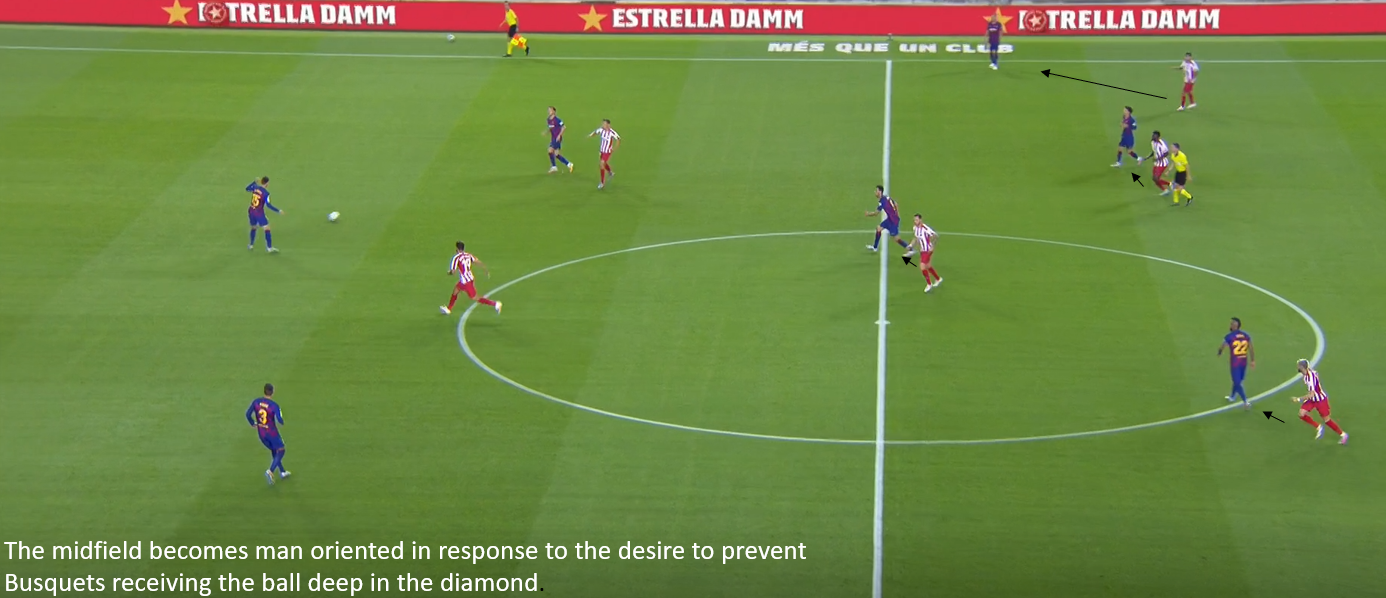

This element is adaptable to the opponent’s system; against Barcelona’s diamond midfield, Atlético Madrid opted for a man-oriented approach where a midfielder would follow Sergio Busquets deep and the wide midfielders would move narrow to mark the other three. Nevertheless, the overarching aim remains the same: force the play out to the full backs by making it difficult for the central players to receive the ball to feet.

The forwards in the 4-4-2 therefore have the potential to create central compression traps whereby their backwards movement is complemented by the forward movement coming from the two banks, thus resulting in the midfield becoming overwhelmed.

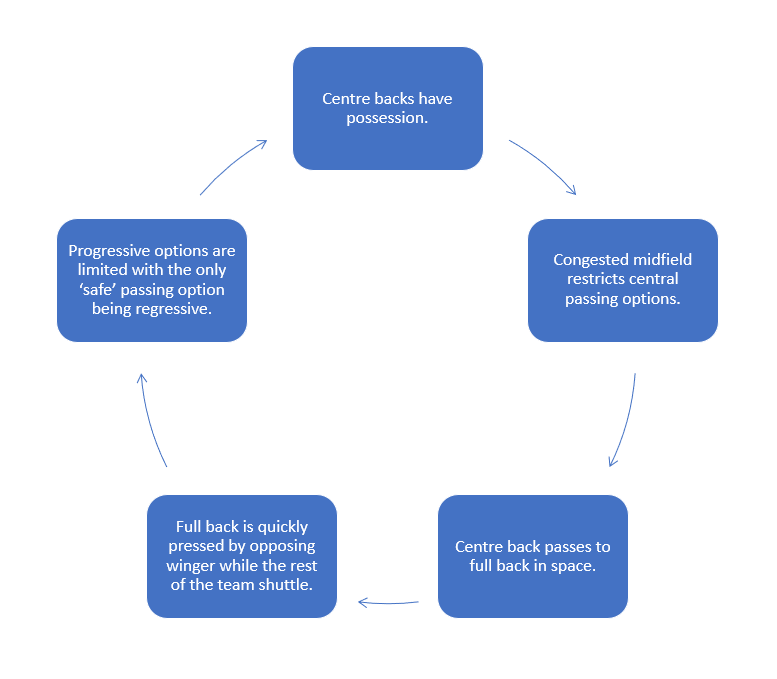

Oftentimes, when the opponent attempt to progress through short passes, a cycle of centre back-to-full back, full back-to-centre back passes will occur, thus creating a war of attrition as the attacking team looks to exploit lapses in concentration which may create space in between the lines.

The defensive 4-4-2 therefore seeks to make the opponent waste time in possession by forcing involvement in an attritional gam, as the central compactness acts a deterrence towards short central build-up and can force long balls or risky dribbles.

The full backs in the system play the most man-oriented role on the flanks during this period of attrition. They must diligently track their opposing winger in wide areas to prevent quick interplay between him and the full back.

In order to do so, they must remain tight in wide areas; if they can’t, the opponent can easily bypass the shuttling midfield, resulting in a centre back having to cover him and exposing even more space. The man-orientation ends if the winger drifts centrally as he will presumably find himself trapped within the congested area of the shuttling midfield.

They will try to will bait the opposing centre back to move further forward forward in an attempt to gain territory and disrupt the midfield’s shape. This strategy is often used by the team in possession to confuse marking schemes, but it also leaves the opponent exposed to the counterattack by leaving space.

This is where the centre forwards become important. A 5-4-1 or 4-1-4-1, for instance, can achieve the defensive advantages of a 4-4-2 with regards to a shuttling midfield, but it doesn’t pose the same central counter attacking threat. Teams that shape up in a 5-4-1 can be forced deep and will often have to sustain crosses, as they will struggle to capitalise on turnovers and threaten on the counter.

1-striker systems also struggle to create compression traps in between the forward and midfield line due to having one fewer player. To achieve a similar effect, one of the wide players must sit forward and narrow, which opens up the threat of them to be exposed on the counter on one of the flanks.

The centre forwards thus become ‘free’ defensive players who can adapt to where the opponent attempts to overload and then pounce upon the space exposed on the counter, while also having a supporting player relatively level to them when possession has been re-gained.

In order to counteract the defensive 4-4-2, opposing sides often use a back three in possession in order to provide a center back with the freedom to roam into the half spaces which are covered by wingers rather than the central players.

As such, this allows the opponent to achieve a 3v2 situation before the shuttling ensues, thus making it a useful tool for gaining territory as the opposing team will be forced backwards, albeit not quite as deep as before the dribble commenced.

This allows one full back to push forward into an awkward zone in between the full back and the winger, both of whom seek to remain level with their respective lines, forcing a midfield to move deeper to cover the potential pass.

4-4-2’s in actuality are not about deep defending, particularly at the start of the game where energy and concentration levels are generally higher. Rather, they seek to force engagements to occur in the midfield area, setting up with a a medium to high defensive line in combination with a low line of engagement so as to congest the opponent’s midfield.

As soon as they are relieved of pressure, these teams try to force the play back to opposing centre backs around the half-way line. This seeks to achieve an equilibrium; staying deep enough to protect space in behind and prevent a dangerous ball from the unmanned centre back while simultaneously staying high enough as to not face a barrage of pressure in dangerous areas closer to the goal.

Fouling occurs fairly frequently as maintaining the shape collectively is of paramount importance, as a dribble or line-breaking pass has the potential to cause disruption to the shape. Defensive success relies heavily on individual duels where unpredictability arises hence generating more potential for gaps to open, as the situation is more reactive and thus less controlled.

This is an undesirable situation when playing a zonal defence, so the best decision is often to foul a player who has found space either by beating a man or receiving the ball so as to quickly minimise the possibility of chaos ensuing.

As such, it increases the value of defending in the middle of the pitch and reduces the risk of making fouls frequently, as potential set-pieces happen in deeper regions where they are less dangerous. The example below is from Carlo Ancelotti’s Napoli where, since the shuttling press was broken, a foul occurred as Atalanta’s Robin Gosens had ample space.

This often manifests itself into a war of attrition, as territory ceded is often marginal and controlled from defending teams’s perspective as they progressively begin engaging lower and lower as the opponent pushes forward. This controlled decline allows for the compact two banks to stay in defensive areas, posing similar problems during build-up as central penetration is made difficult through the central compactness, whilst attacking out wide is halted by the two players and shuttling.

The requirement of the forwards to support the defensive effort, particularly in deep regions to provide the numerical superiorities that are required to cut off passing lanes into central areas often means that transitioning into attack can be difficult and can feature frequent lateral passing and hopeful direct balls.

Therefore, defensive 4-4-2’s prioritize zonal control of all areas of the pitch in deep and middle areas with the sacrifice coming from not being able to press high as a collective unit; doing so would require a dangerously high line to support and maintain the levels of compactness desired.

There is a degree of simplicity to the shape because as long as players hold their respective positions and respond to the relevant pressing triggers, space should be protected. They are effective because of the zonal coverage provided by the narrow four in combination with the compactness that is achievable both horizontally and vertically.

The 4-4-2 being predicated on zonal marking allows the defensive team to be more proactive in how they seek to contain the opponent, with the symmetry between the two banks allowing communication for changes to be easier as you replicate the movement of the person either in front or behind you in most cases.

This allows most teams to be capable of playing the system irrespective of what players they have at their disposal, as its defensive success is predicated on teamwork, cohesiveness, communication, concentration and energy, rather than technical defensive skills as 1 vs 1 duels.

In summary, the 4-4-2 allows the team out of possession a significant degree of control. The compactness, coverage, simplicity, counter-attacking threat and control provided by a 4-4-2 explains why managers such as Carlo Ancelotti, Diego Simeone and Arrigo Sacchi have treasured the shape’s defensive qualities.

By: @Mezzala8

Featured Image: @GabFoligno