Tactical Analysis: Mauricio Pochettino’s Tottenham Hotspur

Before taking charge of Stade de Reims, Olivier Guégan took a tour across Europe to observe several training sessions and matches and get a glimpse of their respective managers’s patterns and tactics. He went to Rome to study Rudi Garcia’s Roma side, he went to Madrid to analyze Diego Simeone’s Atlético Madrid, and he even paid two trips to England to survey Mauricio Pochettino’s Southampton and Tottenham Hotspur sides.

“I was following a set-up before a game against Chelsea. [Pochettino] had taken the ten players who were to start on one part of the field, with offensive and defensive patterns. He was asking for specific things in the use of the ball on high and low blocks. It was extremely meticulous.”

The learning experience has served Guégan well, the 48-year-old having managed Reims, Grenoble, and currently Valenciennes, who find themselves 11th in Ligue 2. But he is far from the only manager who has been influenced and inspired by Pochettino’s body of work.

Born in the rural village of Murphy, Argentina, Pochettino began his playing career at Newell’s Old Boys before leaving his home country at the age of 22, joining the recently promoted Espanyol. He quickly became a mainstay for the Pericos, leading them to their first trophy in 60 years where they would defeat Atlético Madrid in the Copa del Rey Final, before joining Paris Saint-Germain in 2001.

After a three-year spell in France, Pochettino returned to Espanyol on loan, which was soon made permanent. The aggressive, tough-tackling defender spent another two-and-a-half years in Catalunya, before announcing his retirement at the age of 34. He spent a year pursuing a master degree in sports management, before beginning his coaching education.

Photo: Miguel Ruiz

Merely weeks after receiving his UEFA Pro License, Pochettino was appointed as Espanyol manager in January 2009 with the Catalan club mired in the relegation zone. With the Argentine at the helm, Espanyol grinded out their first away victory against Barcelona in 27 years and finished a comfortable 10th place in the league. A fruitful spell followed, with Pochettino gaining plaudits for his high-pressing 4-2-3-1 formation, but he left his post on November 26, 2012 after a 0-2 loss to Getafe left them stranded at the bottom of the league.

He only needed to wait a few weeks before receiving his next opportunity in management, replacing the widely popular Nigel Adkins in January 2013. Despite not speaking any English, Pochettino quickly endeared himself to players and fans and earning praise from Sir Alex Ferguson, who claimed, “In the second half Southampton have been the best team to play here this season,” after United mustered a 2-1 victory in Pochettino’s second game in charge. “We were fortunate to win.”

Bolstered by the arrivals of Victor Wanyama from Celtic and Dejan Lovren from Lyon, Southampton finished 8th in the league, their highest finish since 2002/03, whilst also recording the club’s highest points total since the Premier League’s establishment. Such were his accolades at the South Coast that Tottenham Hotspur decided to hire him on a five-year contract to replace the departing Tim Sherwood.

The following five years would see Pochettino deliver one of the greatest spells in the club’s modern history, with Tottenham narrowly losing the league title to Leicester City and Chelsea in back-to-back years, before losing to Liverpool in the Champions League Final. Pochettino was dismissed on November 19, 2019 with Spurs sitting 14th in the league, but it is only a matter of time before he latches onto his next project, be that Juventus, Manchester United or Real Madrid.

Let’s take a deeper look at Pochettino’s tactical set-up and what made his Tottenham side so successful.

How did Pochettino’s Tottenham approach their build-up?

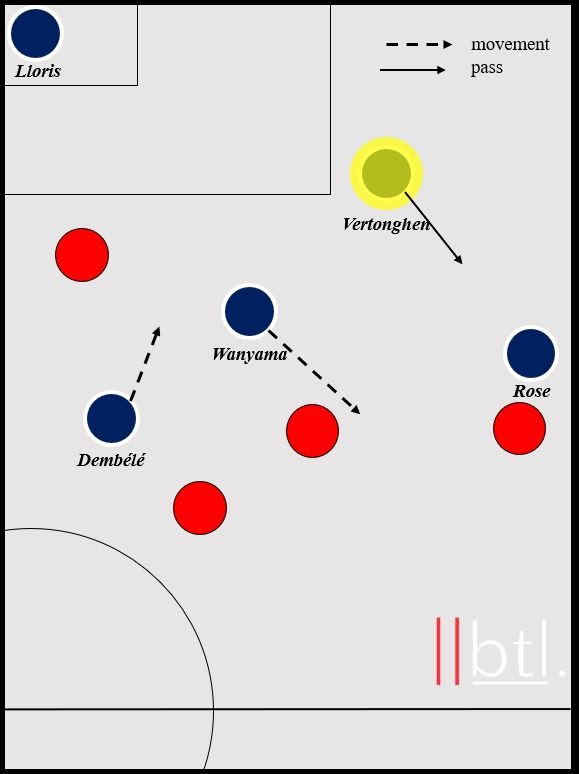

Pochettino varies the amount of players in the build-up according to the opponent; if the opposition presses with one forward, Spurs would use two players in the first phase of build-up, if the opposition presses with two forwards, they use three players in build-up. If the opponent were to press with three strikers close to each other, Pochettino would instruct his fullbacks to remain deep in order to achieve numerical superiority in the first phase.

Whenever the opponent would mark Spurs’s #6, the Spurs players would rotate their positions in order to free up space in central areas in order for the lone pivot to receive the ball. By ensuring that the two midfielders were never in the same area, Pochettino’s side could therefore stretch the opponent’s first line of pressure and creating more passing angles.

When Mousa Dembélé was the deepest midfielder, Wanyama or Eric Dier either advanced higher up the pitch or drifted wide right to allow Kyle Walker (or Kieran Trippier) to push forward. When it was Wanyama or Dier as the deepest midfielder, Dembélé was either pushing higher or drifting wide to allow Danny Rose to push forward.

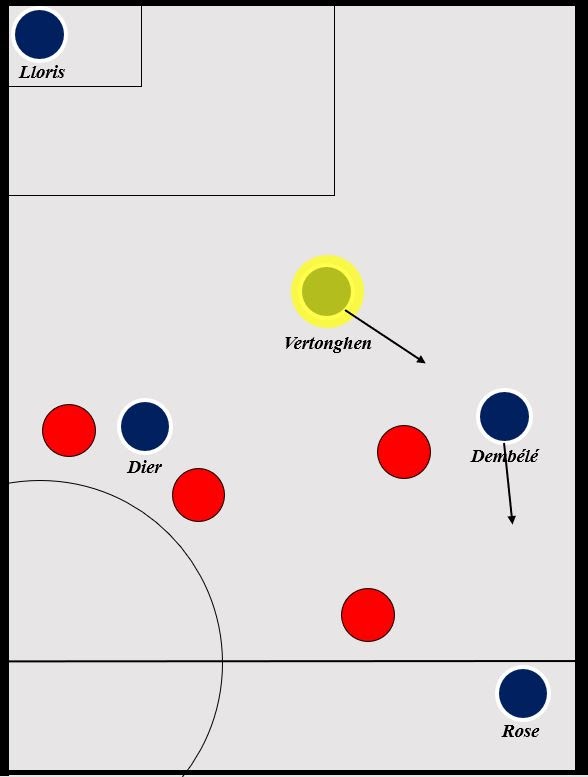

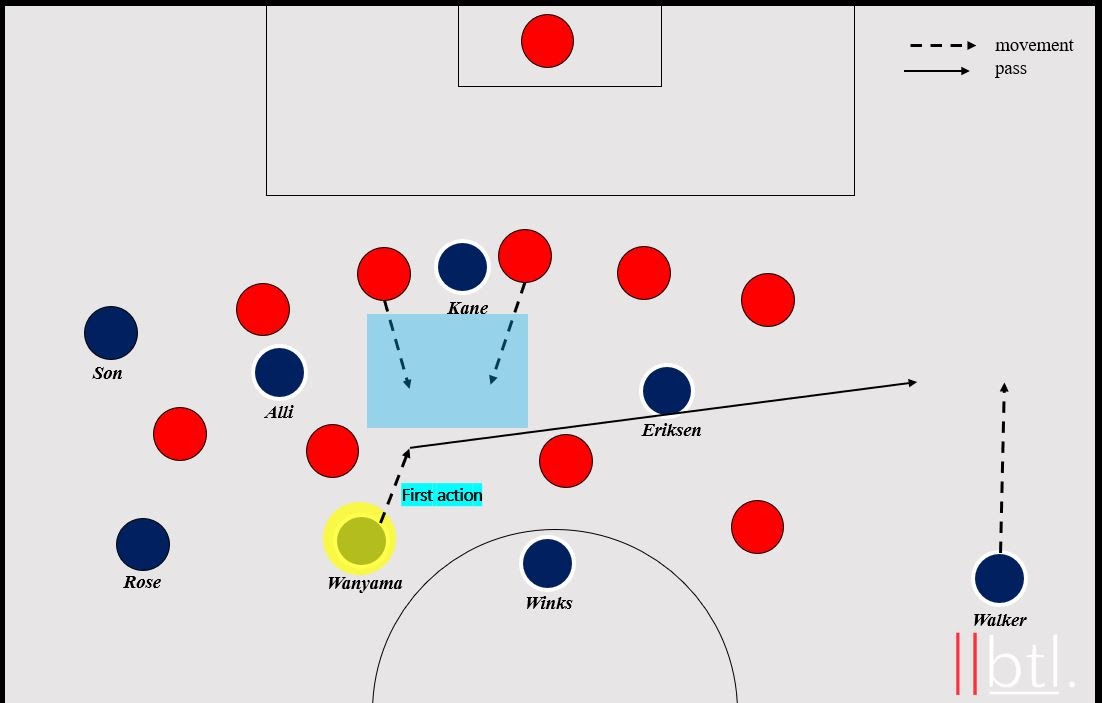

Pochettino played under Marcelo Bielsa during the start of his playing career at Newell’s Old Boys, before reuniting with Bielsa between 1999 and 2002 with the Argentina national team. As a Bielsa disciple, Pochettino follows his principles by using a diamond in build-up, with either three center backs or two center backs and a deep fullback alongside a lone holding midfielder.

This creates triangles on both ends of the pitch, thus facilitating the circulation of the ball from one end to another, whilst also providing the holding midfielder with more space to receive the ball and face the play. It allows Spurs to play in the middle of the pitch and find players higher up the pitch; Wanyama faces the opponent in a deep position and can play a simple pass to Harry Winks in between the lines.

When Tottenham couldn’t build out the back due to the opponent’s pressure, Pochettino instructed his players to bypass the midfield with long balls to Harry Kane or Dele Alli, who were both tall and strong enough to win the aerial duels and second balls.

In this example against Arsenal, Kane controls a long ball from Paulo Gazzaniga on his chest, forcing Granit Xhaka to commit further forward before launching a through ball towards Alli. His compatriot finds an acre of space behind Laurient Koscielny, controls the pass, and chips the ball past Petr Čech. Tottenham would advance to the next round of the EFL Cup only to be eliminated by Maurizio Sarri’s Chelsea on penalties in the semifinals.

If they couldn’t progress the ball through passes up the middle, Tottenham’s center backs would often target the channels with long balls down the flank. This is similar to Jürgen Klopp’s Liverpool, where Virgil van Dijk plays balls down the left channel towards Sadio Mané, forcing the opponent to drop deeper in their own half whilst taking fewer risks themselves than usual.

In this example against Manchester United, Jan Vertonghen plays a lofted pass down the left flank towards Heung-min Son, who finds himself isolated against Jesse Lingard.

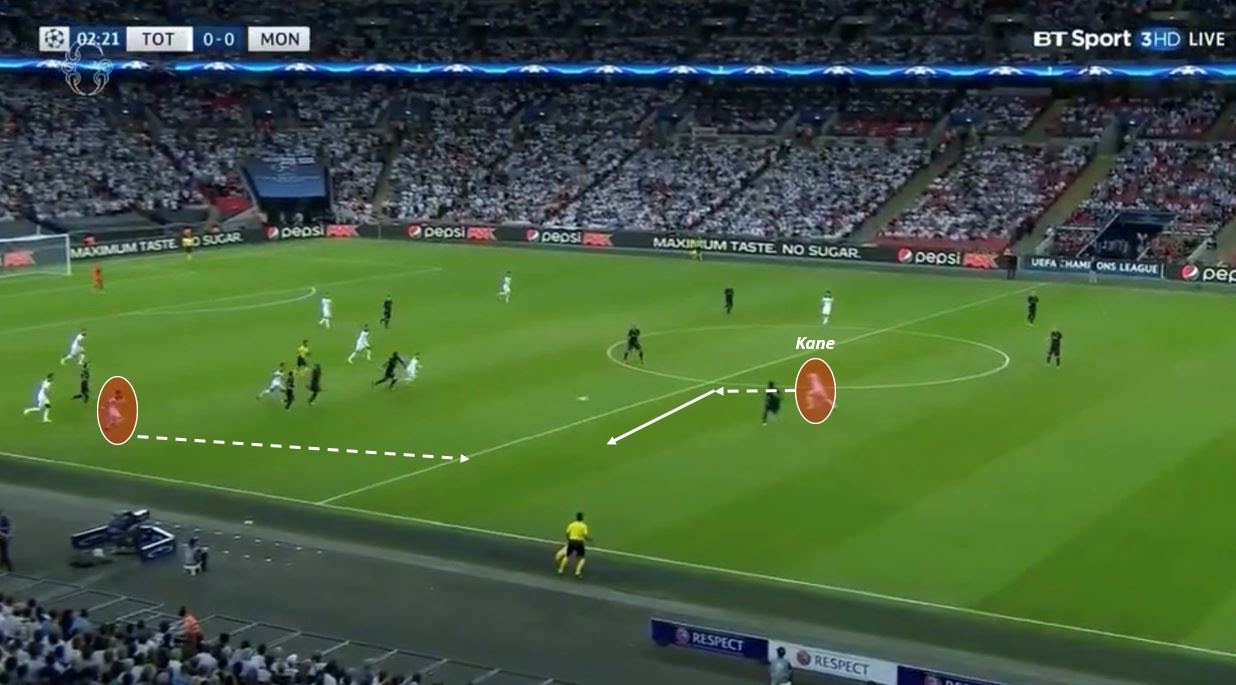

In this example against Monaco, Walker plays a quick pass to Érik Lamela, who dribbles into acres of space on the right flank. The Argentine finds Kane between the lines, the Englishman dropping deep into space to receive the ball before finding the overlapping Walker in an advanced position on the right flank. Kane would often drift wide in order to create numerical overloads and combine with teammates in the final third.

Tottenham’s build-up play is heavily reliant on the usage of diagonals. Toby Alderweireld and Vertonghen often utilized diagonals to break the lines and create space for their teammates, although their fullbacks occasionally played diagonals in order to progress the ball, as seen below with Danny Rose.

This is a common concept in Pochettino’s teams; the center backs consistently receive under pressure before hitting diagonal balls towards the flanks, thus bypassing the opponent and creating chances. This strategy of switching the play proves to be especially efficient if the player is playing on the side of his strong foot. When Vertonghen was sidelined with a knee injury during the first few months of 2016, Pochettino often used Kevin Wimmer as the left-cited center backs.

Tottenham’s defenders effectively used switches of play in order to create more angles to progress the ball and break the lines with long passes. In this example against Manchester United, Walker switches the play to Christian Eriksen on the left flank, whose glancing header finds Rose isolated against Matteo Darmian. Rose finds Lamela advancing towards the edge of the box, and the Argentine forward puts away the third and final goal.

Whilst Pochettino’s players often try to progress the ball centrally through positional rotations, they didn’t hesitate to go long and attempt to win second balls, rather than running the risk of having their central pass intercepted in dangerous areas. Moreover, thanks to Vertonghen and Alderweireld’s immense quality on the ball, the Belgian defenders

Tottenham in the final third

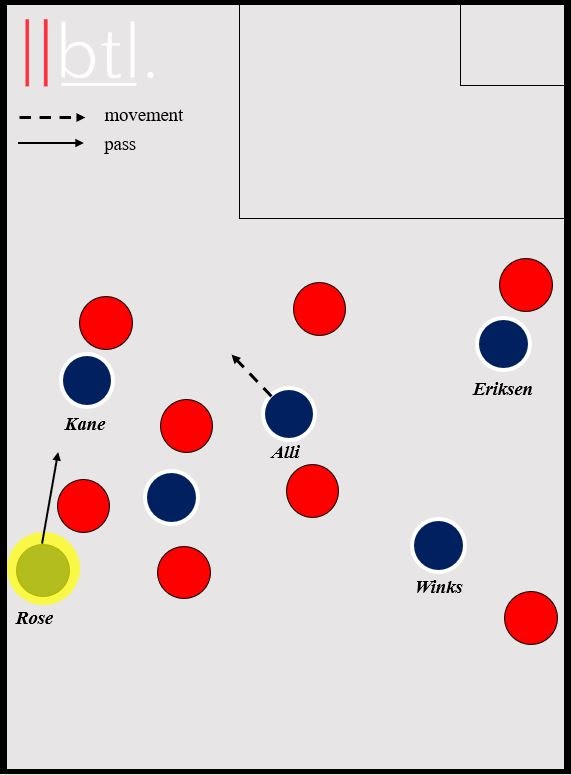

Pochettino instructs his front four to remain narrow whilst one of his fullbacks push high up the pitch to provide width and offer a numerical overload on one flank. In this example against Stoke City, Rose is isolated in acres of space on the left flank, whilst Spurs’s front four are bunched up in the middle in order to quickly combine with one another.

Ensuring that the forwards remain narrow provided unique advantages in terms of link-up play and quick combinations. In this example against Chelsea, Eric Dier roams forward before finding Eriksen between the lines, who glances it into the path of Lamela, who plays a through ball to Kane, who converts the opening goal.

Another benefit of the front four maintaining narrow positions is that the opposite fullback can be quickly found in space for a cutback or cross into the box. Here, Eriksen pins the opposing left back inside, consequently leaving Walker alone in space. Wanyama drives forward before finding Walker, who took his time to receive the pass and send in a cross.

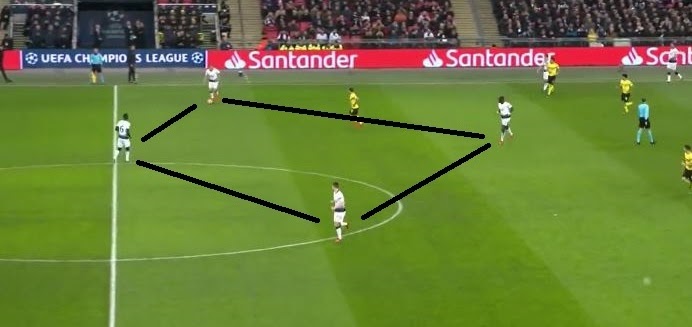

Whilst Tottenham often relied on quick combination play or positional rotations to create space, they also used passes into the channels to find their runners, as seen below in the match vs. Borussia Dortmund.

Pochettino’s style of play is far more similar to that of José Mourinho than Pep Guardiola — not only do his teams operate in a 4-2-3-1, but there is also a stronger emphasis on winning second balls and launching long passes into the channels in order to progress play.

Pochettino’s intense press

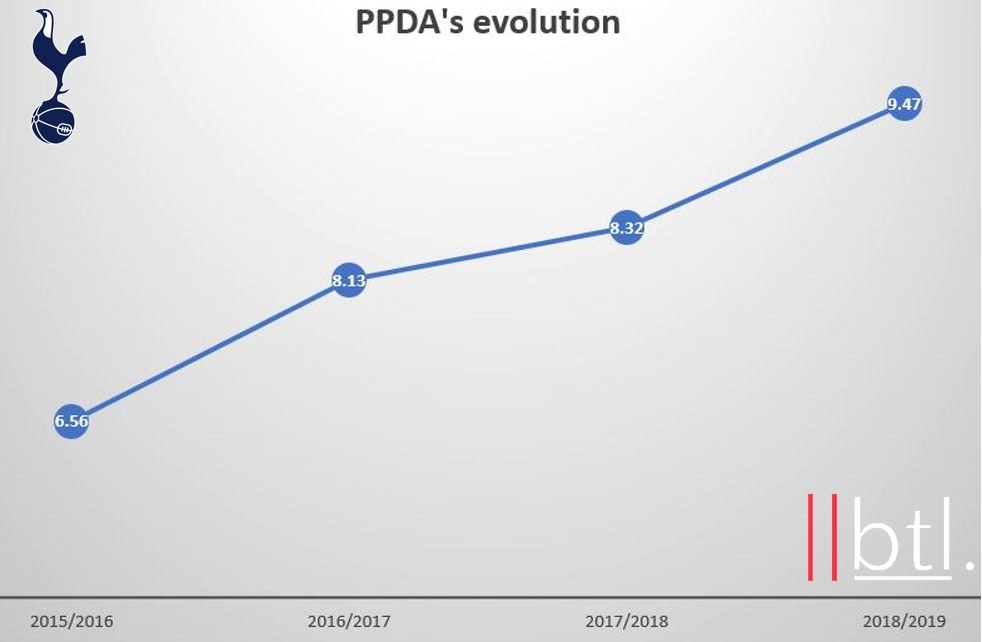

Wherever he has managed, whether that’s Southampton, Espanyol, or Tottenham, Pochettino’s teams have always stood out for the intensity of their pressing. Spurs boasted the most aggressive press in the league in the 2015/16 season with just 6.56 PPDA (Passes Per Defensive Actions), and retained their top spot the following season.

Spurs would cut short passing lanes in the middle of the pitch through man-marking in order to force the opponent to go wide, before putting even more pressure on the opponent through that flank. Tottenham used a risk-averse approach in their pressure in order to force the opponent into playing a long ball, rather than ‘gegenpressing’ and trying to recover the ball in an advanced area.

Spurs were more effective when pressing with only three forwards as they didn’t have to push too many players forward. Their three forwards helped them cut passing lanes on the inside while their full-backs were able to press high without exposing the backline, and if they had enough players in wide areas, they could apply pressure in the final third to win the ball back.

Pochettino was adapted his strategy based on the opponent; against Manchester City, he told his players to only press high in certain periods of time. These periods of high-intensity pressing caught City off guard on numerous occasions while not exposing Tottenham too much as they could remain compact in between the lines.

Tottenham tried to prevent the opponent from creating havoc on the counter by crowding the opposing player on the ball and packing the center of the pitch. The goal of this was to not allow too much time on the ball to the ball-carrier and press the opposition immediately after losing the ball. The entire team focuses on closing down the opposing defenders and winning the ball high up the pitch.

One of the things that Tottenham consistently struggled at was defending the half-spaces. This inability to protect the half-spaces became even more noticeable after Walker’s departure to Manchester City in 2017, as Kieran Trippier and Serge Aurier were far less equipped at defending transitions and recovering to stop the counter. Whilst Pochettino wanted to sign Porto’s Ricardo Pereira, chairman Daniel Levy instead bought PSG’s divisive Ivorian right back to replace Walker.

Pochettino’s man management

Pochettino has worked wonders with the likes of Walker, Alli and Dembélé, helping them reach their potential with intense physical training and clear-cut tactical instructions. But perhaps one of the most underrated parts of the Argentine manager’s repertoire is his man management skills.

During his time at Southampton, Pochettino worked with a teenage Luke Shaw who was quickly establishing himself as one of the biggest revelations in England at the time. However, with Shaw struggling with dietary issues, Pochettino took it upon himself to pick him up from his house before training and make him healthy vegetable smoothies.

“I think with Southampton he achieved the impossible,” remarked Shaw on his former manager. “We were one of the best footballing teams in the league…I do hope that I can play for him again one day. And I think he really wants me to play under him again. He used to call me his son, that’s how good our relationship was. I’ve had lots of ups and downs, but when I was with Pochettino it was only ever up, up, up.”

“He made me feel that I was the best. He’d show me clips of my games and say, ‘You should do this better’. Not in a horrible way. Not that I could have done better, but I should have done better, because he knew I could be better.”

“He’s world-class, not just as a manager, but as a person,” added Adam Lallana, who played under Pochettino from 2013 to 2014. “The way he man-manages his players. He makes you feel good about yourself.”

Throughout his career, Pochettino has earned praise for being willing to give academy players a chance in the first team. At Espanyol, he launched the careers of Jordi Amat, Álvaro Vázquez, and Javi Márquez; at Southampton, James Ward-Prowse, Callum Chambers and Shaw. Pochettino has taken young players such as Harry Winks, Eric Dier, and Kane, and transformed them into players capable of mounting a deep run in Europe’s elite club competition.

What went wrong for Pochettino at Spurs

After eliminating Borussia Dortmund, Manchester City and Ajax en route to the Champions League Final, Tottenham faced off against Liverpool in Madrid. Spurs conceded a penalty in the opening minute when Mané carefully lifted the ball into the outstretched arm of Sissoko, and Mohamed Salah converted from the spot to give the Reds the lead. Pochettino’s side served up a lifeless and tepid performance in the hour and a half that followed, whilst Liverpool took home the first silverware of the Jürgen Klopp era.

From that point onwards, the bottom fell out. The Lilywhites won just three games in their opening 12 matches and were bounced from the EFL Cup by League Two outfit Colchester United. After an atrocious run of form that saw Tottenham take 14 points from 12 games and suffer humiliation in a 7-2 defeat to eventual European champions Bayern Munich, Pochettino was sacked on November 19, 2019, leaving his Spurs side 14th in the Premier League. Upon his dismissal, Pochettino had managed 160 wins, 60 draws, and 73 losses, and had secured a top four finish in each of his last four seasons at Spurs.

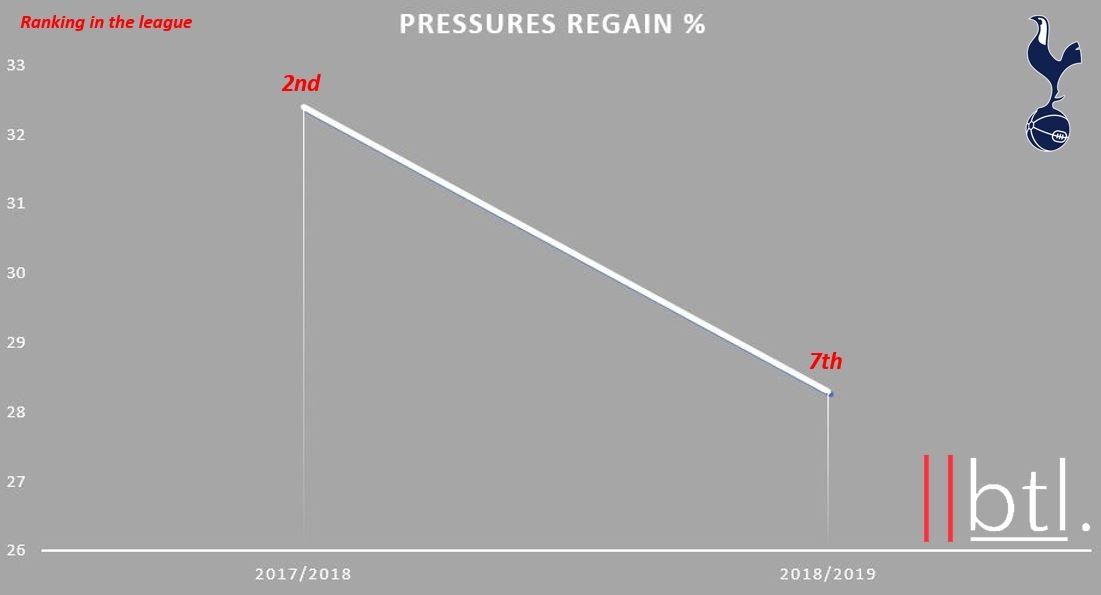

One of the reasons for Spurs’s tumultuous performances over the first few months of the prior campaign is their pressing intensity, or lack thereof. Tottenham’s ability to swarm the opponent with aggressive pressing continuously improved over Pochettino’s reign, although the intensity of the team’s press sharply declined during the final months of his spell in charge.

Pochettino’s double training sessions and the short amount of rest days drove many players to their limit, and when Damir Skomina blew the final whistle in Madrid, the burnout festered even more. A worrying pattern that had emerged during the 2018/19 season became a defining characteristic of a hellish start to the following campaign.

Pochettino’s demanding training methods squeezed the most out of his players, but they also brought them to their limit and engendered a tumultuous end to his time in charge of Tottenham.

Pochettino’s big game record

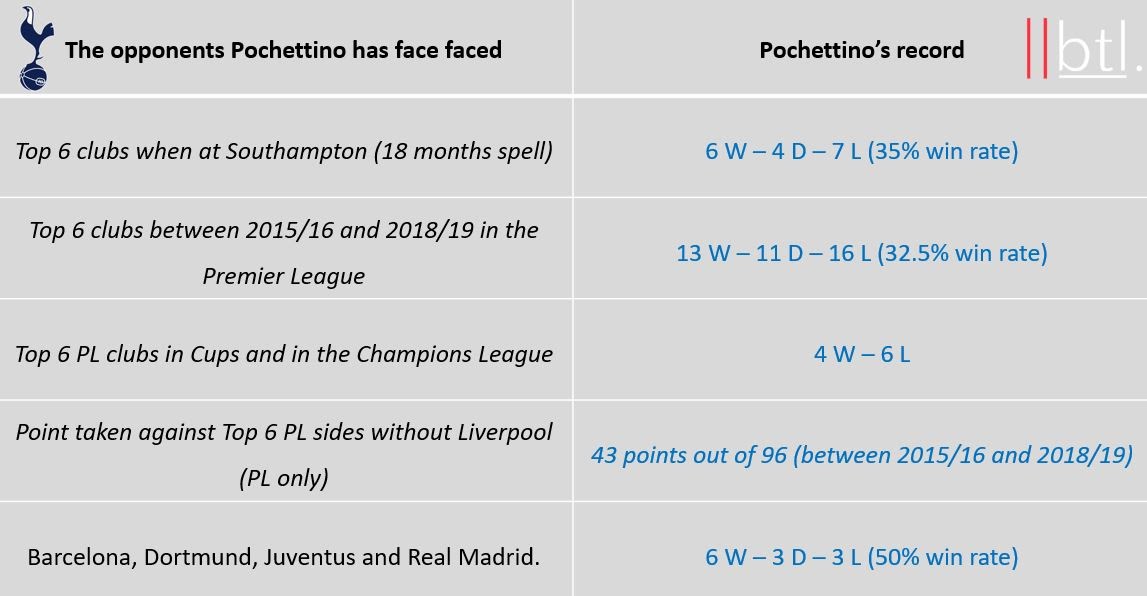

One of the biggest criticisms of Pochettino during his spell in London was his inconsistent big-game record, and to a greater degree, his lack of silverware. In the two years preceding his appointment, Tottenham had mustered four wins, five draws, and 11 losses against top six sides; in other words, a win rate of 20%. However, between 2015/16 and 2018/19, Tottenham’s win rate against top six sides improved to 32.5%.

Tottenham did not lose a single game at home during the entirety of the 2016/17 campaign, their final season at White Hart Lane. Whilst Pochettino’s side boasted a formidable home record, their away record was not quite as dominant; they secured just three wins from 27 away matches against the top six under Pochettino.

Whilst Pochettino deserves credit for transforming the mentality of Spurs players to the point where they could outplay and outwork the likes of Real Madrid and Manchester United, it’s clear that the 32.5% win rate against the top six isn’t good enough for a club that aspires to fight for the title each year. Still, trophies should not be the sole barometer by which a manager is judged; Klopp himself waited nearly four years before hoisting his first silverware at Liverpool.

“We’re going to have the debate whether a trophy will take the club to the next level. I don’t agree with it. It only builds your ego. The most important thing for Tottenham right now is to always be in the top four,” those words from Pochettino in 2019 come as a stark contrast to his statement in 2017, when he said “Our objective is to win the Premier League, to win the Champions League – for me the two real trophies.”

Nevertheless, Pochettino’s achievements at Tottenham go well beyond trophies, and he will be fondly remembered by Spurs fans for taking the club to the edge of glory, even if they never managed to get past the finish line.

Conclusion

Today marks one year since Mauricio Pochettino was dismissed at Tottenham, but it’s only a matter of time before he receives his next opportunity at the top level. He was far from the only culprit of Tottenham’s sharp decline; Pochettino reportedly requested the signings of Bruno Fernandes, Paulo Dybala and Aaron Wan-Bissaka, and his demands to sell Sissoko, Wanyama and Eriksen prior to the 2018/19 season fell on deaf ears. Perhaps his next chairman will be less frugal and more proactive than Daniel Levy, whose penny-pinching contract negotiations caused plenty of discontent in the Spurs dressing room.

Pochettino has been linked with a move to Manchester United, with Ole Gunnar Solskjær struggling to convince in his second year at Old Trafford. Whilst he likely wouldn’t have to tweak the formation, with Solskjær operating in a 4-2-3-1, he may need to find a tall center forward to perform the duty of Kane and win long balls and hold up the play for his teammates. Anthony Martial has impressed in this role, but there’s still plenty he must improve on before he’s at the Englishman’s level.

By: @JKFootball

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / Tottenham Hotspur FC