L’última Dansa: Pep Guardiola’s Final Season in Barcelona: Part 1

At the time of writing, Barcelona have just concluded their final match of the 2019/20 La Liga season and defeated Alavés 5–0. They finished second, five points behind a defensively sound but by no means stellar Real Madrid.

Barcelona seems to be in a state of turmoil, as a disorganized squad seems to be getting even older instead of getting younger in order to prepare for the post-Lionel Messi era. At 33 years old, the twilight of the Argentine’s career is quickly approaching, and with his contract set to expire in 2021, there’s no guarantee he’ll be at the Camp Nou much longer.

Meanwhile, over in Manchester, Pep Guardiola is finishing up a domestic campaign in which Jürgen Klopp’s Liverpool team flew out of the blocks and never looked back in their first league title triumph since 1990. The Citizens were also knocked out of the FA Cup by an Arsenal side managed by Mikel Arteta, Pep’s assistant up until this past December.

Although Barcelona and Guardiola can both salvage this relatively disappointing season by winning next month’s knockout version of the Champions League in Lisbon, they both seem to be in an uncomfortable spot. For a club and a manager who have always been held to the highest standard, a season without total domination is seen as a failure, similar to the 2011/12 season, when the pair ended a seemingly perfect marriage.

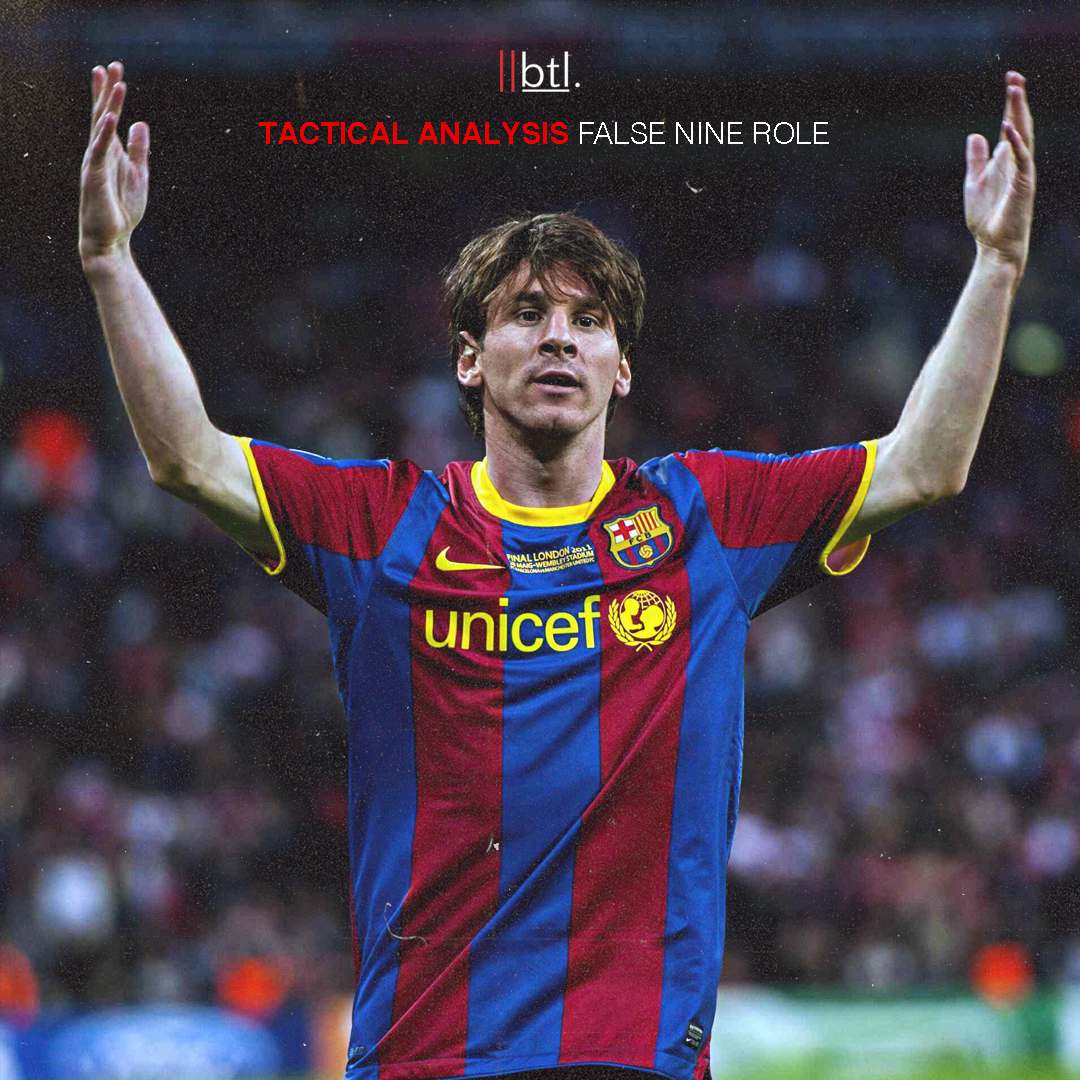

To say that FC Barcelona were the best football team in the world at the end of the 2011 Champions League Final would be an understatement; they were amongst the greatest teams in history, rivaling the likes of Liverpool ’84, Manchester United ’99 and Brazil ’70 for a place on football’s Mount Rushmore.

The Blaugrana side were a year and a half removed from a 2009 calendar year in which they won every competition they competed in (to this date, the only team to win a ‘sextuple’) as Pep Guardiola’s reached the pinnacle of success in his first full year as first team manager.

In Guardiola’s first three seasons, he won three La Liga titles, two Copa del Reys, and two UEFA Champions League titles. In 2011, after defeating Arsenal in the second leg of the Round of 16 — following a questionable refereeing decision to send off Robin Van Persie on a second yellow — Barcelona made easy work of Shakhtar in the quarters, and after an El Clásico semi-final, they found themselves in a rematch of the 2009 Champions League Final.

The 2011 Final was a relatively tight affair in the first half, as Pedro opened the scoring in the 27th minute until Wayne Rooney canceled the opener out seven minutes later. In the second half, two efforts from outside the box, first from Messi, and a second from Spain’s all-time leading goalscorer David Villa sealed Barca’s second UCL trophy in as many years apart.

Photo: Getty

So when it came to the summer of 2011, the objective seemed simple: reload and go again. However, the simple things are sometimes the hardest to execute in football, especially in the case of FC Barcelona. Alexis Sánchez was brought in from Udinese to replace a disgruntled Bojan, who, four years after becoming the youngest ever Barcelona player to feature a league match, was sold to Roma after failing to deliver on his enormous promise.

Sánchez strengthened a thin front line with only three clear first choice options at the time (Messi, David Villa, and Pedro). The signing of Arsenal midfield wizard Cesc Fábregas was well received, albeit not fully thought out.

Fábregas found himself up against the unenviable task of carving out a place in a midfield three of Andrés Iniesta, Xavi, and Sergio Busquets, one of the greatest trios in the history of world football. Three years after returning to his boyhood club, he headed back to London — only this time, Chelsea, not Arsenal. Sánchez, on the other hand, went to Arsenal in the same transfer window, after Barcelona signed Luis Suárez from Liverpool.

The funds for the Fábregas deal could have and should have been used elsewhere in the squad, specifically to strengthen the backline. The only two legitimate centre backs on the books for Barcelona this season were a 33-year-old Carles Puyol and Gerard Piqué. Javier Mascherano — nominally a defensive midfielder — did in fact play most of his minutes for Barcelona as a centre back.

In the aforementioned 2011 tie vs Arsenal, Guardiola started the game with a center back pairing of Busquets, a defensive midfielder, and Eric Abidal, a left back.

Photo: Getty

Whilst Abidal had served the club admirably since his arrival from Lyon in 2007, he had been diagnosed with a tumor in his liver, and at 32, his best years were in the rearview mirror. Despite this, Barcelona allowed backup left back Maxwell to leave midway through the season, who joined Paris Saint-Germain for €3.5 million. They elected to not sign a replacement, instead choosing to rely on Adriano, who had arrived a year prior from Sevilla.

Since the days of Johan Cruyff, Barcelona’s entire identity as a club has been based on possession-heavy, attacking football, but their defense has been just as important to their success as their midfield and attack. Barcelona’s board failed to give Guardiola the reinforcements he needed at the back, and Barcelona paid the price.

Aside from Maxwell, they also parted ways with center backs Henrique, Martin Cáceres and Gabriel Milito, shedding valuable squad depth at the back and forcing Guardiola to lean on defenders from the youth team such as Marc Muniesa and Andreu Fontàs. However, the Catalan manager had a plan up his sleeve to cope with his team’s defensive weaknesses.

One of Guardiola’s tactical masterstrokes during his four years in Catalonia was how the attack became more and more focused on maximizing the otherworldly talent of Messi. When the Argentine first debuted under Frank Rijkaard, he mostly featured on the right wing. However, Guardiola, who prefers his wingers to stay high and wide, realized that this would diminish Messi’s ability to drift around and carry the ball from deep areas.

As such, he chose to experiment with Messi as a “false nine,” giving him the freedom to drop into midfield and pick up the ball in areas where he can penetrate from deep.

During both of Barcelona’s Champions League-winning seasons under Guardiola, Messi was more often than not flanked by Samuel Eto’o and Thierry Henry in ‘09 and Villa and Pedro in ‘11. However, Villa dealt with injuries in 11/12 and only made 24 appearances in all competitions, allowing Sánchez to make an instant impact with 41 appearances in his first season playing on both wings.

Although the Chilean did not offer the same goal threat as Villa, his dynamism and relentless work rate gave Barcelona another dimension in attack. Moreover, given Piqué’s injury problems, Guardiola was forced to rework his tactics and sometimes stray away from a 4–3–3, the principal formation for both the club and the manager.

Sometimes, Barcelona would line up in what was back four by name only. Dani Alves would play in a position that can only be described as “the right” where he maintained the width on that side of the pitch in attack, while the opposite full-back (Abidal until Adriano took over due to his injuries) played more traditionally and balanced, forming a sort of 3-man defense.

Guardiola also experimented with 2 defender formations and even a singular defender in an inverted pyramid (1–2–3–4) formation, stretching the limits of what is known as Total Football. Fábregas or Iniesta would fill in on the left wing in the team sheet, but mainly played infield on the left half space.

In Fábregas’s case, the Catalan played up top with Messi as double “false 9s” where they took turns dropping into midfield or making runs in behind while the opposite winger (Pedro or Sánchez) would hold the width on the left flank. But when Barcelona played in their more conventional formation, both Sánchez and Pedro would start as wingers, with La Masia youngsters Isaac Cuenca and Cristian Tello filling in in case of injury or suspension.

Mascherano played his usual role for Barcelona, filling in for Piqué and Busquets when required, and he would go on to make the second-most appearances in the side, often playing as a center back. In the absence of any defenders or attackers due to injury or squad rotation, Guardiola’s first instinct was to flood the pitch with more midfielders as Thiago Alcântara and Seydou Keita.

In Part 2, I will discuss the storylines and outcomes of the season, ending in the conclusion of Guardiola’s reign as Barcelona manager and the one-year sabbatical that followed his departure.

By: @YoPixrre

Featured Image: @GabFoligno