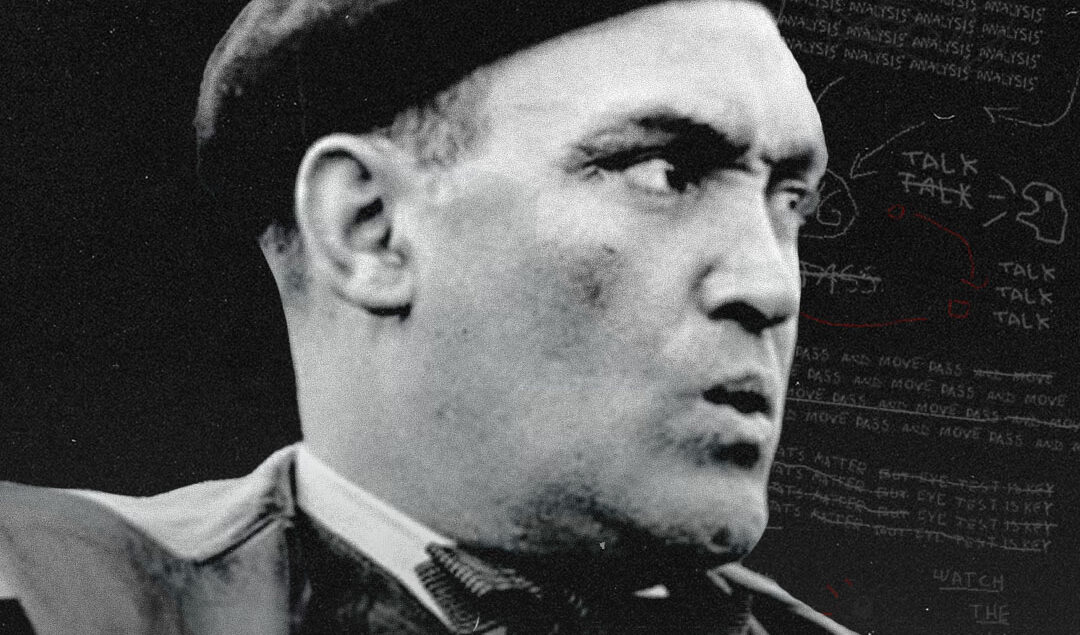

Cândido de Oliveira: Portuguese Football’s James Bond?

If you’re a fan of Portuguese football or have just taken a look at their Super Cup results on your score app, you might have noticed that the Portuguese Super Cup is called the Supertaça Cândido de Oliveira. Apart from being one of the only tournaments in world football to bear the name of a person, the story of Cândido de Oliveira is something you’d usually find in your dad’s old World War Two books.

An independent film has already been made in Portugal called Cândido – O espião que veio do futebol (or Cândido -the spy who came from football), so before let me take you on a journey to the early 20th century to experience the life of this amazing man so that when Hollywood inevitably makes a movie about him you can tell all your friends why Liam Hemsworth isn’t a good fit for the role.

Our story starts at the tail end of the 19th century in Fronteira, a small town in the west of Portugal, where on September 24th 1896 Cândido was born. His early life would be marked by tragedy however, as before he reached the age of 6 he was to be sadly orphaned. Thus in 1905 he ended up at Casa Pia, Portugal’s biggest orphanage.

Founded all the way back in 1780 at the initiative of Maria I the Queen of Portugal in order to alleviate the effects of the devastating Lisbon earthquake of 1755, the institution is the biggest educational centre in all of Portugal. Casa Pia has always had a strong commitment to sports and it was there that Cândido discovered his athletic abilities alongside his love for football.

His talent proved enough for him to join Benfica in 1911, and he made his debut for them three years later. He would spend six years at Benfica before joining some of his fellow Casa Pia graduates in founding a new club, Casa Pia Atlético Clube. The new team immediately went on to defeat Benfica in a regional cup competition as well as winning the Lisbon Regional Championship and the Lisbon Cup.

In 1926, he hung up his boots and was immediately approached by the Portuguese FA to take over as manager, as he had been the captain in Portugal’s first ever international game against neighbours Spain. His first major tournament was the 1928 Olympics where he guided Portugal to a quarter final appearance before Egypt eliminated them. This would remain Portugal’s best finish at a major competition until Eusébio came along in 1966 and led them to a third-place finish.

Throughout his managerial career he still worked for the post office and wrote for several Lisbon publications. This rather quiet life spent between postal work, football management and sports journalism could not however, escape the turmoil that Europe was undergoing at the time.

Since the ‘keep politics out of football’ brigade was not around back then, De Oliveira decided to play an active part in the fate of his country leading up and during the second World War. During his lifetime, Cândido de Oliveira had seen his country endure numerous hardships and internal upheavals leading up to the 1910 revolution, which ousted the royal family.

The subsequent first republic was equally weak and presided over a catastrophic and humiliating entry into the first World War. This led to the 1926 military coup d’état, which established the Ditadura Nacional (national dictatorship). Just as Adolf Hitler finally abandoned any remains of his dreams of becoming a painter as he gained power in 1933, Portugal got its very own dictator, Antonio de Oliveira Salazar.

A conservative nationalist, Salazar used brutal forms of repression through his PIDE secret police to keep his population in line and prevent underground activities such as those by communists from securing a foothold in Portugal. Cândido de Oliveira had been a staunch antifascist throughout his life and he expressed his views both publicly and privately on numerous occasions, as he criticized the regimes of Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini, Francesco Franco and Antonio de Oliveira Salazar.

Bulgarian Football’s Harrowing Descent into Corruption and Mediocrity

His first run-in with the regime had already come during the ‘30s when he was questioned by the regime after his some of his Belenenses players refused to perform the Nazi salute in a Portugal-Spain game. All throughout his journalism work he was constantly censored and harassed by the regime as well.

Cândido’s work in the postal system and his high profile in the lofty circles of Lisbon as well as his democratic views made him an ideal target for the British intelligence during World War Two. The British SOE (Special Operations Executive) was founded after it became clear that the Germans would have the mastery over the European continent in order to support resistance movements around Europe.

Another very important activity was surveying the various nominally neutral countries in Europe and trying to prevent their entry on the side of the Germans or facilitate an entry on the Allied side. Whilst Spain was of particular interest, under the fascist leadership of Francisco Franco, Portugal was equally important. After Germany’s invasion of Poland, Salazar had declared a neutral stance in the war and later signed a non-aggression and neutrality pact with Spain, looking to profit from trade with both factions.

The Brits’ main concern was the heavily anti-communist stance of the regime, which aligned their ideology with that of Germany in that respect, whilst similarly disavowing the violent nature of Germany’s leadership. Cândido’s main task was to report to the British SOE about the activities of the Portuguese regime, especially regarding the more extremist politicians in Salazar’s circle.

The so-called Shell Network (named that way because most of its employees worked in the oil industry) of which Cândido de Oliveira was part, had the task of reporting on any movement of German nationals in Portugal and preparing a possible resistance in case the right-wing Germanophile elements in Salazar’s government got their wish and Portugal joined the Axis.

Leading up to 1942, when the war was still going in Germany’s favour, the German regime drafted Plan Felix for a possible invasion of the Iberian Peninsula and the seizure of Gibraltar. The British government was concerned that the nationalist regimes of Franco and Salazar would not put up much of a fight and join the Axis powers. All throughout that time a propaganda battle was unfolding in Portugal as well as a more covert battle in the political scene for influence between German and British agents.

It was in this climate that Cândido de Oliveira became Agent H.204 and Agent H.700. In his new guise he organized a network of radio-telegraphists who could maintain communications in the case of an invasion as well as maintaining a network of possible resistance fighters and informants. Any vital German communication going through his post office would also be held back in time for it to be photographed and sent to England, and of course to be delayed from reaching its intended targets as much as possible.

How a Betting Scandal Saw Hellas Verona Win Their Only Scudetto

Ultimately, Salazar managed to maintain a balance between the Anglo-Portuguese Alliance, which has existed since 1373 and the need of the Axis for the country’s resources. Despite a British embargo, Portugal maintained a contraband network between them and Germany selling their resources for gold bullion, looted from the various occupied peoples of Europe. Cândido de Oliveira’s ultimate goal of creating a resistance towards Salazar’s regime ultimately never came to fruition, as the need did not arise and he was arrested by the secret police, who had been tracking his moves, in 1942.

Cândido was shipped to Cape Verde to the Tarrafal concentration camp, a place where the regime had shipped any vocal dissenters since the 30s. In his book “Tarrafal-The Swamp of Death” he describes the camp, located on a peninsula with no drinking water and the most malaria-infested part of the island, where he managed to survive against all the odds.

Through the many beatings he sustained through the hands of the regime he lost most of his teeth and it would only be in 1945 that he fully regained his freedom, never able to work for the British again as he was compromised. He founded arguably Portugal’s largest footballing publication A Bola soon after and reactivated his old network of antifascists.

He has been said to have taken part in the build-up to the “ Mealhada” Revolt, which ultimately failed in deposing Salazar. During the 50s he continued his work for A Bola and it was in 1958, whilst covering the World Cup in Sweden that he contracted pneumonia, which ultimately killed him. Salazar’s hour did not come for ten more years after that and he was deposed in 1968 after suffering a stroke.

By: Eduard Holdis / @He_Ftbl

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / ZeroZero