Inside the Politicised World of Hungarian Football

On the 24th of May 2023, the Romanian Cup Final was set to be disputed between current holders Sepsi OSK and Universitatea Cluj. The game ended in a 0-0 draw and extra time was not sufficient to split the two teams. Then in the penalty shootout, Sepsi managed to cling on and reverse their fortunes after missing their second spot kick. At roughly the same time as this was unfolding, DAC Dunajská Streda were missing out on the Slovak Super Liga by two points, after coming in as runners-up the previous season too.

These seemingly random sets of results from two Eastern European leagues seem to have no connection to each other, but they are in fact the best performances by Hungarian-backed teams in their respective countries. As western football audiences are getting more and more used to regimes funding their football clubs in order to sportswash their image, audiences in Serbia, Romania and Slovakia are witnessing the steady rise of politically backed teams under Budapest’s control.

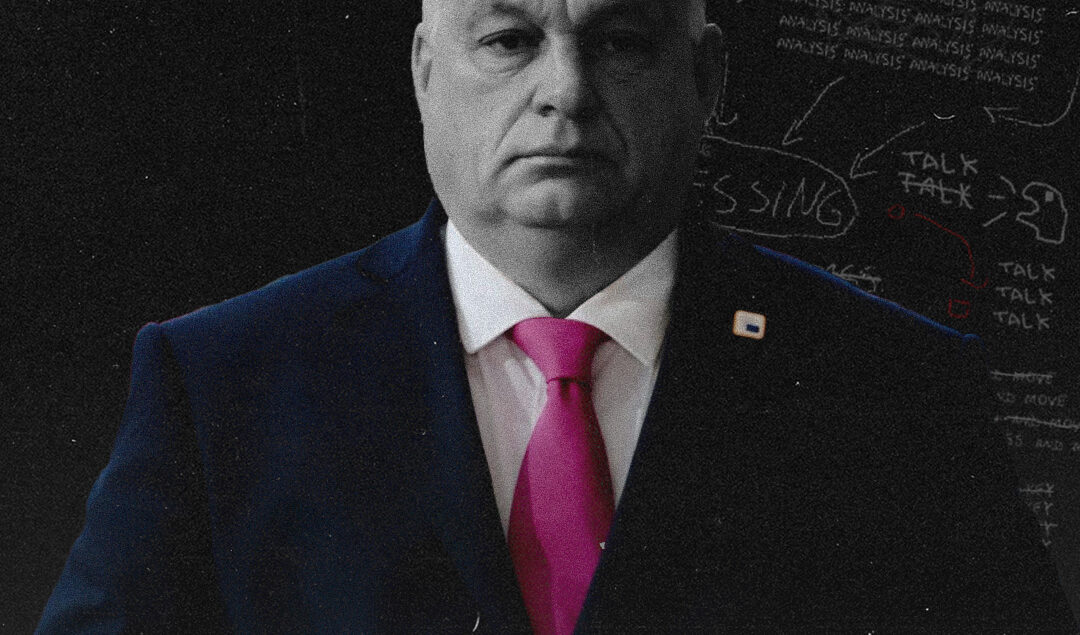

Key to the whole enterprise is Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban and his love of football. An avid fan of the game, Orban watches as many as six games per day and rarely misses the chance to attend Champions League and World Cup finals in person. Growing up in rural Hungary, he idolized the Mighty Magyars team of the 50s and played youth football for Videoton.

A professional footballing career was not on the cards for him, so he chose to study law in Budapest, where he would regularly play five-a-side football with fellow Fidesz founders. Fidesz, the party he co-founded, started out as an anti-Communist youth movement, and after the collapse of the Hungarian Communist regime, Orban became a member of Parliament.

At the time, his party was a far cry from the right wing anti-European machine of hate, intolerance and censorship it is today, espousing liberal, pro-European values. However, after an embarrassing loss in the elections in the late 90s, Orban decided to change tack and leaned more and more towards the right. His love of football remained undeterred, however, and he would still regularly play five a side football with his closest friends, many of them Fidesz co-founders.

As his star rose in the landscape of Hungarian politics, it also veered more and more to the right, and between 1998 and 2002, he enjoyed his first term as Prime Minister, where he would still attend his five-a-side games, but now with an official escort. The power of football was not lost on the aspiring dictator, as in 2006, Ferencvaros supporters and security guards stormed the national television headquarters on the anniversary of the failed 1956 Hungarian revolution.

After being reelected in 2010, football would be used both as a weapon for propaganda and as a reward for his most loyal followers. In Felcsút, the Pancho Arena, named after the nickname Spanish fans had for Ferenc Puskas, was built in 2014 with a capacity of nearly twice the town’s size. The town itself is the place where Orban grew up and its mayor — Orban’s childhood friend — has tripled his wealth under the regime and recently bought out over 192 regional newspapers.

Borussia Mönchengladbach: The Golden Years of a German Football Behemoth

Orban’s friends and lackeys are also strategically placed in the world of Hungarian football with Videoton being owned by construction oligarch István Garancsi, Sándor Csányi, the country’s richest man being the head of FA and MTK being owned by Fidesz founder Tamas Deutsch. The flurry of stadium building did not stop in his hometown, however, as smaller teams such as the one owned by Fidesz deputy minister András Tállai and larger ones like Ferencvaros received new grounds, in addition to the newly built national Puskas Arena.

The chief contributing factor to this heavy investment is a new scheme, which allows corporations and oligarchs to divert profits towards sporting or cultural endeavors and avoid paying taxes. As such, any self-respecting oligarch will choose to buy up real estate around his club’s stadium and invest in the club’s facilities rather than hand the money over to the state.

As such, it is no surprise that Hungary has spent more on football than on teachers or doctors. Almost all of the clubs in the Hungarian first division are owned by Orban’s associates and their stadiums, and especially the Pancho Arena, are a hotbed for meetings between politicians and oligarchs. The league is broadcast through MTVA, a state-owned broadcaster, and they seem to really want to broadcast the league as they regularly pay almost double for the rights to the Hungarian league compared to the Champions League.

As with most nationalist and revisionist regimes, the Orban administration likes to evoke the past when it comes to football and their politics. In the world of football, this is visible through the naming of virtually every stadium after a member of the Mighty Magyars, as though the particular name of the stadium will elevate the level of football in the country. In their external politics, the lands of their neighbours with Hungarian minorities are closely monitored and supported, closely accompanied by continuous moaning about a treaty signed more than 100 years ago.

Giacinto Facchetti: The Best Left Back You’ve Never Heard Of

With the landscape of Hungarian football secured, Orban and his regime are now funneling taxpayer money to clubs in Romania, Slovakia and Serbia from the aforementioned regions. Estimates as to the total investment vary, but a figure of around €50-60 million seems to be the consensus. In a top 5 European league, that would probably buy your club a new left winger or a lick of paint for its stadium, but in the Eastern European leagues, these funds can revamp clubs from top to bottom.

We will start in Romania, which has the largest population of Hungarians in the vicinity of Hungary. Out of the one million Hungarians living in Romania, most of them are located in the Székely Land in Transylvania. It is there that we find the two clubs backed by Hungarian state funds, namely the aforementioned Sepsi OSK and FK Csíkszereda, based in the two biggest cities of the Székely Land.

Sepsi are based in Sfantu Gheorghe, the unofficial capital of the Szekely Land and a city where the majority of its residents identify as Hungarian. The club was founded in 2011, as the city never had a professional football team. Behind its founding stands László Diószegi, a bakery magnate native to Sfantu Gheorghe. The majority stake of the club, namely 51%, is owned by Hodut Rom, a subsidiary of a holding company owned by Karoly Varga, one of Orban’s childhood friends.

Since the club was founded, they have rapidly climbed up the divisions to reach the Romanian top flight and are now poised to disrupt the established clubs at the top of the league. Key to their rapid success is the funding they receive, namely around €6.19 million, which has gone mainly into expanding the club’s infrastructure and facilities, as the money cannot be pumped directly into the wages of the squad.

For the wages and transfer fees, the Hungarian sponsorship comes from the private sector with OTP Bank and the MOL energy giant both sponsoring or having sponsored the club. This investment not only ensured that the club had facilities of a very high standard compared to the rest of the league, but also the highest revenue from sponsors in the whole league.

The old municipal stadium received a refresh, and in 2018, the club decided to build itself a completely new ground, the Sepsi OSK Arena. The rumored reason for this decision seems to allude to the fact that the old stadium is still owned by the Romanian state. In 2021, the new arena held its first game and the site, where it was built is owned by the same company led by Karoly Varga.

The second club based in Romania that has received Hungarian backing is FK Csíkszereda, also based in one of the most important cities of the region Miercurea Ciuc. Unlike Sepsi, the town has a long footballing history, with the club continuing to exist under various names since 1904. The fortunes of the club were not in the best of shapes around the mid-2010s when chairman Zoltán Szondy wrote to the Hungarian regime asking for funds for a footballing academy. Around €4 million has been made available to the club since then, with most of it going into training pitches and academy facilities.

This has propelled the Csíkszereda academy to become one of the best in Romania, expanding into neighbouring cities and large towns with smaller affiliated training centers. The first team has climbed up to the second tier and a future where they act as a feeder club to Sepsi can easily be envisioned. Both club’s supporters and ultras are mostly Hungarian and tensions between them and opposition fans are present at nearly every game.

When Fourth-tier Calais Came Within Inches of Winning the Coupe De France

Key to those are the Hungarian flags displayed by them and more importantly the flag of the Szekely Land, which until recently was a sort of unspoken taboo topic in Romania. The visual elements are supported by nationalist songs and irredentist rhetoric and Orban has been relishing in this cesspit of ethnic tension. He has openly supported both teams on his social media accounts and has attended multiple games, once controversially draped in a flag carrying the image of Greater Hungary.

The response from Romanian fans has been equally vitriolic and several clubs have been fined for the behaviour of their fans and a game has even been suspended. As some of Romania’s oldest and most successful clubs are experiencing sharp declines or are divided and the league itself falls further and further down UEFA’s pecking order, Sepsi might be poised to win their first league title, which will no doubt cause even further scrutiny towards their backing and intentions.

This heavy investment in football is part of a larger package of funding received by the Szekely Land from Budapest that promotes Hungarian culture and infrastructure in the area. However, football and ice hockey seem to be the darlings of the decision makers, as other areas cannot be so easily used for propaganda purposes in such a short time.

A few hundred kilometers North West, in Southern Slovakia Hungarians are the largest ethnic minority, with a total of around 450,000 Hungarians living in Slovakia. In the two districts of Komarno and Dunajska Streda, they form the majority of the population and in these two districts we can find the two clubs backed by Budapest. The first one is FC DAC Dunajská Streda, who used to be a yo-yo club during the 90s but now are on their way to becoming title challengers season upon season.

The key figure of this massive improvement is Oszkár Világi, the deputy CEO of the Hungarian petrol and energy company MOL and its subsidiary in Slovakia. As always, Világi is another one of Orban’s pals, although he maintains that he and his club are apolitical and he cares only about the sporting endeavours of his project. The club has nonetheless received over €7.42 million from the Hungarian government and has built itself a new stadium, the MOL arena and a new academy.

This academy is headed by Világi’s daughter since 2018 and has continually applied for funds from the Hungarian regime. Around 300 players have been playing in the academy, most of them from the surrounding regions and Hungary itself and is one of the most advanced in Slovakia. Just like in Romania, the ethnic tensions between supporters of this club and supporters from the rest of the league have flared over at times.

All the way back in 2008, police intervened between fans of Slovan Bratislava and DAC and it was reported that the main focus of the police was on the DAC fans. From there, the club has increased its nationalist rhetoric and Hungarian flags are a mainstay in the stands, as well as the Hungarian national anthem that is played before every game. Of course, as stated by Világi on multiple occasions, the club is completely apolitical, even though during election times the club’s ground acted as a place where signatures are gathered for the local Hungarian party and the party’s election song was played at the venue.

Just like in Romania, we can also find a secondary team that plays in the second tier and has not received as many funds as DAC, namely Komarno. The club’s full name reads KFC Komarno and fans usually abbreviate its name to KKK. I promise you I am not making this up: there are no connections to the colonel and his chickens or a certain terrorist organization that is very fond of hoods.

Luton Town Before the Premier League: Bonkers Presidents, Formula 1 Tracks and Pop Idol Managers

In 2014, the mayoral candidate from the local Hungarian party asked Orban for his assistance both in his campaign and with the region of Komarom. Whilst the would-be mayor had more of an educational focus, suggesting a new agriculturally focused high school Orban suggested a new stadium for the team. The mayor then stated that the money for the stadium was suggested as being from the leftovers of other projects.

Since then, around €5.57 million have been given to the club and the reconstruction of the stadium and the academy facilities is still pending. The dissonance between the request of the locals and Orban’s response paints a larger picture where many voices from the respective communities have criticized the Budapest administration’s heavy focus on football in their funding. According to reports, funds are always ready for footballing endeavours but local administrations need to jump through a higher number of hoops for other projects.

For the last club on this list, we need to head to Serbia, more specifically to the region of Vojvodina, where most of Serbia’s more than 180,000 ethnic Hungarians live. The situation here is very much different than the ones in Romania and Slovakia in terms of inter-ethnic relations. Serbia is Hungary’s only neighbour that has signed a cooperation agreement with them.

Whilst the rest of the surrounding nations view Hungary as a rogue state due to their right wing, revisionist and pro-Russian rhetoric, Serbia has continually improved relations with its northern neighbour. Both countries have similar views on topics like immigration, LGBTQ rights, religion and wish to maintain their peoples as “pure” as possible. Both of them have historical grievances, Hungary still evoking Trianon with every possible occasion and Serbia still moping about the former Yugoslav territories.

Did Bayern Munich Really Save Borussia Dortmund at the Beginning of the 2000s?

It was only natural that these two anti-European, counter-progressive states would align themselves with each other and of course with their big daddy in Moscow. Therefore, the energy and atmosphere surrounding the local club FK TSC, or FK Bačka Topola, is the complete opposite of the ones in Romania and Slovakia. TSC have been around since 1913 and have always had a strong Hungarian fanbase, but spent most of their time in the lower leagues.

Much like their counterparts mentioned before, they have risen through the ranks of Serbian football all the way to a second-place finish, which they achieved last year. During this time, around €14 million have been spent on the club, a club which many view positively as a source of excitement and diversity in a league that is basically a duopoly formed between Partizan and Red Star. János Zsemberi, a local multi-millionaire, has acted as the club’s chairman and main sponsor and is now head of its academy.

Like with all the other clubs mentioned here, Orban is ever present, opening dormitories in the academies, cutting ribbons for new stadium developments and of course attending games from time to time. When there is nothing to unveil and all the ribbons are safely tucked away, he usually voices his support for these clubs on social media. The main question remains however, what is this all for? Why are hundreds of millions of Hungarian taxpayer money being spent on football, more often than not on projects outside the country?

In a way, football is on its way to becoming a new form of conquest. Whilst you cannot invade your neighbour to take back your lands, you can use sport to project your power in those countries. Imagine a scenario where the Slovak, Romanian and Serbian leagues all have Hungarian champions. It might not be the battlefield victory many nationalists dream of but, it would be as close as feasibly possible.

A Lesson in Club Mismanagement: How Hertha Became Berlin’s Second-Best Club

Besides the soft power projection and gratifications of Orban’s delusions of grandeur these investments are the most basic modern form of bread and games. Part of the many loaves doled out by the Hungarian administration ensure that Hungarian voters abroad know who to vote for. Since 2010, Hungary has made increasingly heavy-handed inroads into securing dual citizenship for its diaspora, with varying degrees of success.

In Romania, the issue was not viewed as damaging to the Romanian state, whereas in Slovakia, an announcement was made that any citizen applying for Hungarian citizenship would be stripped of their Slovak one. A further effect of this situation was that in 2014, the Hungarian regime announced that Hungarians abroad would be able to vote in the elections, with special ballots being made for them that featured only the parties available and not the individuals within them.

As football becomes an ever-stronger marketing tool and is used more and more as a political tool, Hungary is at the forefront of this new age. However, as usual, the flames of ethnic tensions and xenophobia are fanned by this approach, continuing to create an ever dirtier and seedier image of modern football.

By: Eduard Holdis / @He_Ftbl

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / Jean Catuffe – Getty Images