Politics and Football in Turkey

Since it began with Greeks playing pick-up games in the neighborhoods of Istanbul during the Ottoman Empire, football had been and still is the most popular sport in Turkey. As years passed football became a national phenomenon with the foundation of a national league in 1959. During the early dates of the league football fans mostly consisted of rich elites who could afford the expensive tickets. However, as the sport grew bigger it accumulated more and more fans from all around the country and from various socioeconomic statuses (Ulkemizde Futbolun Dogusu.)

Fan violence started to become a problem during this period, as more fans started attending matches and as rivalries between clubs intensified. The 1970s and ’80s were the decades that revolutionized Turkish football. First, a small team from a minor coastal Black Sea town won the national title and major Turkish clubs started to have early success at the European level. These early successes led to the golden age of Turkish football during the late 1990s and early 2000s when Galatasaray won the UEFA Cup and the national team finished third in the 2002 World Cup (2002 Dunya Kupasi: Altin Sayfa).

As the beautiful game grew popular within the country, politicians could not stay away from the influencing power of football. 7th president of the Turkish Republic, Kenan Evren, was the first politician who directly involved with football. In Evren pressured the parliament and the ministry of sport to pass a law that enabled the promotion of the Turkish Cup winner to the first division, which was the capital’s team, Ankaragucu. Evren believed a successful football team from the nation’s capital will signify the power of the government (Ozdil).

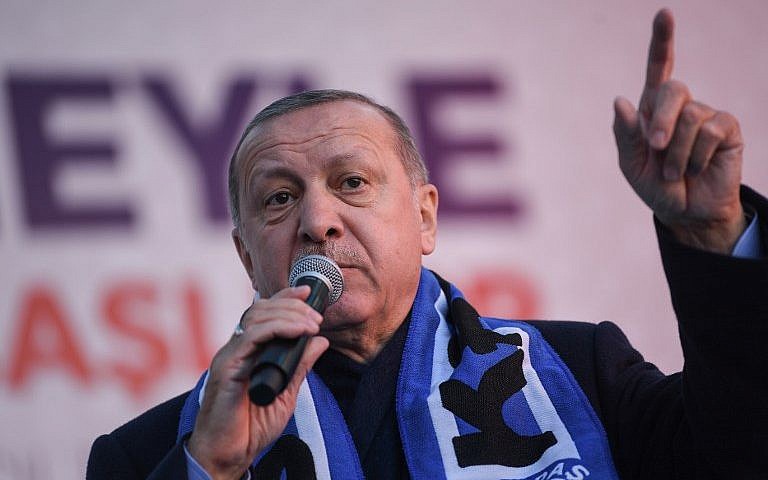

When Turkey’s current president Recep Tayyip Erdogan was elected as a prime minister in 2002, people believed the government’s influence on the game would rise, as Erdogan himself had played amateur football in his youth and was a big fan of the game (Erdogan: I enjoyed 5 titles in my football career).

As years passed, football, politics, and government continued to be associated more and more. Since 2002 Erdogan and the AKP government used their influence over football through direct and indirect interventions to increase and maintain their political power and influence over Turkish people.

Law 6222

Fenerbahce is one of the most successful teams in Turkish football history with 19 league titles and many more national and continental honors. However, the early 2000s were both successful and frustrating for Fenerbahce fans. The team won the title in 2005, 2007, and 2011 but lost the title on marrow margins in the last weeks in 2006, 2008, 2010, and 2012 (Tarihce).

On the 16th of May 2010, Fenerbahce faced Trabzonspor and needed a win over one of its fiercest rivals to clinch the league title. After 90 minutes of intense football and never-ending pressure, Fenerbahce could not find a winner and the game ended 1-1. Even though Fenerbahce could not beat Trabzonspor their fans were celebrating in the stadium and they were even running on to the field to share their celebrations with the coaching staff and players. The only situation that would allow Fenerbahce to win the title was if their opponent Bursaspor had dropped points in their own home game which they did not (Fener Taraftarina Anons Skandali).

So why were the fans celebrating such a devastating loss? Because the stadium announcer received fake news that Bursaspor drew 2-2 in their home game and announced that in the stadium. Fenerbahce fans thought their team had won the title and celebrated with their players and coaches. When the news that Bursaspor had won the league reached Fenerbahce stadium the joy of glory quickly turned into anger and frustration. Fans started to protest the board, players, coaches, and referees.

Fenerbahce’s stadium and the surrounding neighborhood were quickly packed with fans who were furious that their team lost the title. The protests continued all night and fans were violent against police forces, which ended with injuries among both fans and police forces. After the violent events, the Turkish government believed government intervention was necessary to stop these events and the parliament started working on a law that would decrease violence throughout football and other sports.

The Turkish Grand National Embassy passed law 6222: “The Law on the Prevention of Violence and Disorder in Sports” on 31st of March 2011 with the aim of reducing violence among football fans. Law 6222 offered many new regulations that the government believed would be beneficial to stop the violence. The 4th article demanded the establishment of Sport Security Councils to monitor stadiums, fan meeting points, and training grounds.

These Sport Security Councils were given the rights to govern and monitor home teams, which were given the responsibility to monitor and establish a safe environment for fans. 6222 also strengthened the security against banned materials such as flares, flags with large sticks, and offensive banners (6222). However, fans believe this law increases control and pressure over the public rather than stopping fan violence.

Emre Doruk, a Galatasaray fan and a season ticket holder before the law, states that: “The government tries to control football as it controls media and business world. They do not want independent football fans who do not support their political views. The only reason they fine Galatasaray fans is our protest is against Erdogan in 2011 (Doruk).”

In what Doruk recalls, President Erdogan and then the president of Housing Development Administration of Turkey (TOKI) Erdogan Bayraktar were both delivering speeches during the opening ceremony of Galatasaray’s new 50,000 stadium Turk Telekom Arena.

There had been rumors that TOKI had provided substantial financial support for the Stadium’s construction and Bayraktar tried to take pride by saying TOKI was the power behind the stadium and was later booed by Galatasaray fans. When Erdogan took the microphone to silence the crowd’s boos were even louder which led to him not finishing his speech and leaving the stadium (Başbakan Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Türk Telekom Arenada Acilis Konusmasi Yapdi Ancak…).

Many Galatasaray fans like Doruk believe this was the reason why the government was against the freedom of fans (Doruk). Patrick Keddie, the author of The Passion: Football and the Story of Modern Turkey, interviewed Basar Yarimoglu, a member of Football Supporters Europe. Yarimoglu states that 6222 is a law that only focuses on punishing but not educating fans and supporters. He also states that more and more oppression will make fans more violent rather than make them obey the laws (Keddie, 144).

A major update was implemented on the law in 2019 that received more and more protests from fans. The new update meant that stadium bans for violence would now consist of longer terms, the security of stadiums would now be the responsibility of police rather than private security firms, and social media insults against fans, players, and referees were now also under the monitor of law (Sosyal Medyadan Provokasyona Ceza Geliyor).

Photo: AFP Photo

Social media’s installation to the law created major unrest between fans as they believe social media should be a platform where every fan had the right to support their beliefs. Many fans protested by adding 6222 to their Twitter usernames and using 6222 where they would normally curse players and referees. Nalcalilar, the supporters’ group of first division team Konyaspor, released a statement against the new revision in the law.

The group suggested that the government’s approach to sports fans was wrong. They believed the best solution to the violence problem was the education of fans rather than implementing authoritarian bans against them. Several other fan organizations supported Nalcalilar and started the hashtag #BuOyunTaraftarlaGuzel which meant this game is beautiful with fans and received support from thousands of fans (#BuOyunTaraftarlaGuzel).

Passolig System

Law 6222 was not the only attempt by the government to improve the control over fans. Turkish Football Federation and AktifBank, a bank owned by pro-Erdogan billionaire businessman Ahmet Calik (Ahmet Calik Forbes), started an online card-based electronic ticketing system called Passolig in 2014. Passolig’s website identifies itself as a system that “allows fans and their families to safely enter stadiums and enjoy matches peacefully without any stress.

Not only financially beneficial, but Turkish football will also maximize safety and security in the stands with Passolig Card, leaving all the negativity in the past. This card will bring significant new advantages to the clubs and their fans (What Is Passolig?).” The system requires every football fan to sign up to the Passolig website with their national identity numbers and to pay yearly membership fees that are nearly $15.

The system was widely criticized by fans as they believed this was another attempt from the government to control and monitor football fans. Kaan Ozden, a lifelong Besiktas fan and ex-season ticket holder, believes Passolig is just a rip-off and protests the system.

Ozden says he would not renew his season ticket as long as the Passolig system is in place. He adds they are ripping off fans by taking more than $15 from each fan. “There are more than a million Passolig cardholders, let’s say one card costs nearly $15 so Aktifbank makes more than $15 million a year just by monitoring and selling online tickets (Ozden)

Numbers also suggest more and more fans protested the system as audience numbers took a massive hit in 2014-15, the first season where the system was fully functional. The system cooperation with Law 6222 uses cameras inside stadiums to identify sections of the stadium where violence occurs and anti-government slogans are shouted. “Fans fear the system will be used to blacklist supporters based solely on their opposition to the government (Christie-Miller)”

Gezi Parki Protests and Carsi

In late May 2013, Erdogan announced that one of the only remaining parks in central Istanbul, Gezi Parki, would be destroyed in order to rebuild an old Ottoman-era military house. This news led to small demonstrations against this ruling by environmentalists who believed Gezi Parki was one of the only green spaces left in downtown Istanbul.

However, police used violence to stop these protesters and protests grew bigger and transformed into a nationwide protest against Erdogan’s totalitarian regime (Timeline of Gezi Park Protests). Football fans were also prominent in these protests as Galatasaray, Besiktas, and Fenerbahce jerseys, flags and scarves were a common scene during these protests.

Photo: Mstyslav Chernov

These fans, who normally hate each other during matches unified under a common idea and created a fan union that united the three big Istanbul teams, Istanbul United (Wood). Carsi, Besiktas’s ultras fan organization were the most active fan group during these protests as they were all out against Erdogan and his politics.

Carsi had been known for their leftist stand for years and obtained the A of Anarchy as their logo (Norval). The majority of protesters believed Carsi were the power against police brutality during the protests and protected women and children during the occurrence of violence (Turan, Ozcetin).

Kaan Ozden is not a Carsi member but had been attending Besiktas games since he was a child and states Carsi are the driving force behind the world-famous Besiktas fans, who hold the unofficial record for the loudest voice recorded in a football stadium (Beşiktaş o Rekoru Böyle Kırmıştı!). Ozden told Carsi had suffered hits both from the government and the Besiktas board after their open political stance against Erdogan.

He adds “Our board is not supporting Carsi as they were before, they are not giving them the good seats in the stadium, they are backing newly-found groups who are more neutral politically and they are doing that because they are scared of Erdogan (Ozden).

What Ozden recalls is possibly terrifying for other football fans in the country as their political views can threaten their existence and power in the stadiums. The idea of being politically pressured by a party is strict against the ultras’ belief and Erdogan’s totalitarian politics affects leftist groups.

Kasimpasa, Osmanlispor and Basaksehir

The Erdogan government does not intervene in football not by just limiting the fans’ rights and freedom but by supporting teams that have close ties with the government. In Turkey, each municipality that runs a city is assigned to create a sports club that helps the youth in the city to participate in sports. However, during the AKP era, these local governments thought of these municipality teams as a way to showcase the power of their local governments.

According to an article by newspaper Sozcu, there are 21 professional football teams, 26 professional volleyball teams and 36 professional teams owned by local governments (Seçim Sonrası Merak Edilen Soru ‘Belediye Takımlarına Ne Olacak?’). Columnist Ibrahim Yildiz argues that these municipality teams are illegal and should all be closed. He adds that the law makes local governments responsible to promote amateur sports in their region to help young athletes but limits these clubs to remain amateur (Yildiz).

Local governments create an unequal playing field by making these sports clubs professional, as they exploit the revenues of municipalities for their football-related expenses. Longtime Fenerbahçe president and one of the most powerful figures in Turkish football, Aziz Yildirim was also against these government-owned teams as he suggested all government-owned professional football clubs should be closed and they should not be allowed to participate in professional leagues (NTV Spor). As Yildirim recalls these teams should not be competing to become successful against professional teams their goal should be promoting and developing young Turkish players.

Other than government-owned teams, the AKP government were closely linked with three different private football clubs throughout the last decade, which were named project teams by the fans. Recep Tayyip Erdogan was born in the Kasimpasa neighborhood of Istanbul, so fans were not surprised when the local team Kasimpasa had three promotions in succession to reach the first division in 2007. After two relegations and promotions, the Istanbul team came back to the first division in 2012.

Erdogan invited the Kasimpasa players and coaches congratulating them on their success and publicly posed with a shirt signed by everyone at the club. “I hope that the people of Adana will understand that it is only natural for me to support the team that represents the place where I was born,” the president said (Yokhin). After their last promotion, Kasimpasa was bought by billionaire businessman Turgay Ciner who was close ties with Erdogan and the club made several big-name signings such as Andreas Isaksson and Ryan Babel.

Photo: Ozan Kose / AFP

Since 2012, Kasimpasa had been a regularly successful team in the first division, never coming close to relegation. After their “Kasimpasa Project” the AKP government started to back Osmanlispor from the nation’s capital Ankara. The team is owned by Osman Gokcek, the son of ex-Ankara mayor Melih Gokcek. The team’s name Osmanlispor translates into Ottoman Sport Club and their stadium is designed like an Ottoman castle.

“The use of Ottomanism is an AKP trope, intended to appeal to conservative, pious voters with both Islamic symbols and a swashbuckling aura of manly conquest (Keddie). Osmanlispor tried to build a religious fanbase that supported Gokcek and his political power” (Keddie, 70-74). However as Melih Gokcek lost Erdogan’s support and was taken from office in 2017, Osmanlispor found its cruel fate and was relegated a year after (Aziz Yıldırım: Alex Büyük Olsaydı Şu Ana Kadar Bir Takım Çalıştırırdı.). The Osmanlispor Project was not successful as the government wanted and now participates in the second division.

Istanbul Basaksehir is probably the largest and the most popular government-backed team that exists in Turkish football. The biggest and most successful of the local government-owned teams was Istanbul Buyuksehir Belediye which was owned by the local government of Istanbul. The team was a regular in the first division but was disliked by fans.

Emre Doruk says: “They were owned by the city’s government, they did not have any fans and were the team with no mission (Doruk).”. However, it all changed in 2014 when the team moved to the conservative neighborhood of Basaksehir and was renamed Istanbul Basaksehir Football Club. The team was also privatized and was bought by a group of investors led by Goksel Gumusdag, the nephew of the First Lady of Turkey, Emine Erdogan.

Erdogan even participated in the opening game of Basaksehir himself, scoring a hat trick that demonstrated his old football skills were not gone (Keddie). Over the years Basaksehir turned into a stellar title favorite and claimed second place twice and finished third for one time. Erdogan even once called Basaksehir fans to the games as the teams’ fan numbers were not as high as he wanted (Cumhurbaşkanı Erdoğan: Başakşehir Gençliği Tribünleri Doldurmalı).

However, the team could not win the title that Erdogan and the government hopes for but Erdogan’s goal to create a challenger to Istanbul’s giant teams were successful as Basaksehir looks like a team that would not be successful for not just one year but for a long term (Pitel). The reason for Erdogan’s support for these three clubs can be linked to the protests he had received from Besiktas, Galatasaray and Fenerbahce fans during the Gezi Parki protests and he aimed and succeeded in building a new football club that had loyal fans both for the game and for himself and his party.

Conclusion

During the Erdogan era, Turkey has had transformational changes from women’s rights and abortion to freedom of the press throughout the country, making Erdogan the second most influential leader in the history of the modern Turkish Republic, after the founder of the nation, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk. His efforts to change and rebuild the Turkish football scene show the importance of football for Turkish football and how it is not valued as a game in Turkey but as a lifestyle.

By: Anonymous

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / Anadolu Agency

Works Cited

“#BuOyunTaraftarlaGuzel Hashtag on Twitter.” Twitter, Twitter, 2 July 2019, twitter.com/hashtag/ BuOyunTaraftarlaGuzel?src=hashtag_click.

“2002 DÜNYA KUPASI: ALTIN SAYFA.” TFF Tarihcesi, www.tff.org/default.aspx?pageID=299. “6222: The Law on the Prevention of Violence and Disorder in Sports”

“Ahmet Calik.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, www.forbes.com/profile/ahmet-calik/#620fd5ac497f.

“Ankara Mayor Melih Gökçek Leaves Post to Put End to Political Saga.” Hürriyet Daily News, www.hurriyetdailynews.com/ankara-mayor-melih-gokcek-resigns-121530.

“Aziz Yıldırım: Alex Büyük Olsaydı Şu Ana Kadar Bir Takım Çalıştırırdı.” NTVSpor.net, NTVspor, 2 Apr. 2018, www.ntvspor.net/futbol/aziz-yildirim-alex-i-bu-kadar buyutmeyin-5ac2245994d4895090a65631.

“Başbakan Recep Tayyip Erdogan,Türk Telekom Arenada Acilis Konusmasi Yapdi Ancak…” YouTube, YouTube, 15 Jan. 2011, www.youtube.com/watch?v=uvjctYt-GUA.

“Beşiktaş o Rekoru Böyle Kırmıştı!: İnanılmaz… Video – Beşiktaş, Liverpool, Çarşı – Sporx TV.” SporxTV, www.sporx.com/tv/futbol-spor-toto-super-lig-besiktas-besiktas-o-rekoru-boyle kirmisti–inanilmazSXTVQ61007SXQ.

Christie-Miller, Alexander. “Is Turkey Targeting Soccer Hooligans or Collecting Names? Fans Are Suspicious.” The Christian Science Monitor, The Christian Science Monitor, 5 Oct. 2014, www.csmonitor.com/World/Middle-East/2014/1005/Is-Turkey-targeting-soccer-hooligans or-collecting-names-Fans-are-suspicious.

11

“Cumhurbaşkanı Erdoğan: Başakşehir Gençliği Tribünleri Doldurmalı.” Haberler, Hurriyet.com.tr, 14 Apr. 2018, www.hurriyet.com.tr/sporarena/cumhurbaskani-erdogan-basaksehir-gencligi tribunleri-doldurmali-40805216.

“Erdoğan: I Enjoyed 5 Titles in My Football Career.” DailySabah, Www.dailysabah.com, 13 Nov. 2017, www.dailysabah.com/football/2017/11/14/erdogan-i-enjoyed-5-titles-in-my-football career.

“Fener Taraftarına Anons Skandalı.” Sabah, Www.sabah.com.tr, 16 May 2010, www.sabah.com.tr/ spor-haberleri/2010/05/16/fener_taraftarina_anons_skandali.

Keddie, Patrick. “How to Build a Turkish Title Contender from Scratch.” Turkey from the Terraces, Turkey from the Terraces, 20 Dec. 2017, turkeyfromtheterraces.com/stories/2017/12/19/ how-to-build-a-turkish-title-contender-from-scratch.

Keddie, Patrick. “The Ousting of Ankara’s Eccentric Mayor Shakes up Football in the City.” Turkey from the Terraces, Turkey from the Terraces, 9 Nov. 2017, turkeyfromtheterraces.com/ stories/2017/11/8/the-ousting-of-ankaras-eccentric-mayor-shakes-up-football-in-the-city.

Keddie, Patrick. The Passion: Football and the Story of Modern Turkey. I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd, 2018.

Kolbasi, Mert Kazim, Doruk, Emre, Ozden, Kaan. “Besiktas, Galatasaray and Politics.” 26 Oct. 2019.

Norval, Edd. “A Movement for Society and Self-Improvement: Beşiktaş’ Çarşı Ultras.” These Football Times, 29 May 2018, thesefootballtimes.co/2017/04/13/a-movement-for-society and-self-improvement-besiktas-carsi-ultras/.

12

Ozcetin, Burak, and Omer Turan. “Football Fans and Contentious Politics: The Role of Çarşı in the Gezi Park Protests.” SAGE Journals, 6 Apr. 2017, journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/ 10.1177/1012690217702944.

Ozdil, Yilmaz. “’Her Dönemin Şampiyonu Gazeteciler’in Puan Tablosu Ne Olacak?” Hurriyet, Hurriyet, 19 Sept. 2010, www.hurriyet.com.tr/her-donemin-sampiyonu-gazeteciler-in- puan-tablosu-ne-olacak-15815628.

Pitel, Laura. “Political Football: ‘pro-Government’ Club Shakes up Turkish League.” Financial Times, Financial Times, 29 Mar. 2018, www.ft.com/content/d18a2dc4-2dfe-11e8- a34a-7e7563b0b0f4.

“Seçim Sonrası Merak Edilen Soru ‘Belediye Takımlarına Ne Olacak?’.” Skor Sozcu, 1 Apr. 2019, skor.sozcu.com.tr/2019/04/01/secim-sonrasi-merak-edilen-soru-belediye-takimlarina-ne olacak-1120832/.

“SKANDAL!” Lig TV, 16 May 2010, tr.beinsports.com/haber/skandal.

“Sosyal Medyadan Provokasyona Ceza Geliyor.” CNN Türk, 17 July 2018, www.cnnturk.com/spor/ diger-sporlar/sosyal-medyadan-provokasyona-ceza-geliyor.

“Tarihce – Fenerbahçe SK.” Fenerbahçe, www.fenerbahce.org/kulup/tarihce.

“Timeline of Gezi Park Protests.” Hürriyet Daily News, 6 June 2013, www.hurriyetdailynews.com/ timeline-of-gezi-park-protests–48321.

“What Is Passolig?” Passolig, www.passolig.com.tr/nedir.

13

Wood, Stephen. “How Gezi Park Brought Together the Ultras of Galatasaray, Fenerbahçe and Beşiktaş.” These Football Times, 11 Oct. 2018, thesefootballtimes.co/2017/03/28/how-gezi park-brought-together-the-ultras-of-galatasaray-fenerbahce-and-besiktas/.

Yildiz, Ibrahim. “Belediyeler Futbol Takımı Kurabilir Mi?” Haberturk.com, 21 Sept. 2019, www.haberturk.com/ibrahim-yildiz-belediyeler-futbol-takimi-kurabilir-mi-2524084-spor.

Yokhin, Michael. “The Rise and Rise of Kasimpasa.” ESPN, ESPN Internet Ventures, 24 Dec. 2013, www.espn.com/soccer/blog/name/93/post/1841004/headline.

“ÜLKEMİZDE FUTBOLUN DOĞUŞU.” TFF Tarihesi TFF, www.tff.org/default.aspx? pageID=293.