The Dark Side of Colombia’s Beautiful Game: Narco-Football, Money Laundering, and Mass Murder

Like many South American nations, football spearheads sporting interest in Colombia. The passion can be found at international tournaments amidst a sea of yellow, with exuberant fans flocking in their droves to cheer on Los Cafeteros.

But less than 20 years ago, football in Colombia was a sport that went hand in hand with the undesirables in society, in an era where shots fired in the community were more prevalent than shots at goal.

Photo: Vice

Drug Cartels Move into the Boardroom

The Orejuela brothers of the Cali Cartel headed one of the largest, deadliest drug cartels that Colombia has ever seen. In 1979, Miguel Rodríguez Orejuela bought a majority shareholding in his boyhood club, América de Cali.

The cartel viewed a successful football club as the perfect mechanism to launder money. Player transfer fees and wages were raised illegitimately to figures that would be suspiciously excessive even today, and any cash received on the turnstiles increased tenfold.

An eye-watering amount of money was laundered through América de Cali in a 20-year period, shaping its squad to compete for both domestic and international honours. Although the Copa Libertadores proved to be ultimately out of reach, Miguel and Gilberto Rodríguez Orejuela’s finances oversaw the domestic golden years at the once-great club.

Photo: AFP

Pablo Escobar, head of the Medellín Cartel and an avid football fan as well, also bankrolled his beloved Atlético Nacional until his death in 1993. The notorious drug baron’s affluence enabled Atlético Nacional to defeat Paraguayan opposition and lift the 1989 Copa Libertadores for the first time in their history.

The fall of Escobar consequently paved the path for the Cali Cartel to establish and oversee what was once the blueprint of the Medellín Cartel’s operations. America’s War on Drugs now had a new poster cartel, one in which then-United States President Bill Clinton’s sights were fixated upon.

An executive order was penned with the new super-cartel firmly in mind. Signed off by Clinton in 1995, Order 12978 included four names, all of whom were affiliated to the Cali Cartel. Twelve years prior, Colombian minister Rodrigo Lara Bonilla had released his own list, including six professional football clubs that were strongly linked to drug trafficking. Bonilla was assassinated at the hands of an Escobar hitman a year later.

‘Clinton’s list,’ as it was later coined, reaffirmed Bonilla’s investigation by highlighting América de Cali as a suspected front to launder ‘dirty’ cartel money. The sanctions in Clinton’s list were fierce, and in turn, the repercussions for América de Cali and their board members started the rot.

The 1995 executive order put a stop to any financial transactions between American businesses and the football club. All board members’s assets were frozen, and the negative press surrounding the club resulted in current and future sponsors running for the hills.

América de Cali’s steady decline after sanctions were imposed resulted in the club’s relegation to Colombia’s second tier in 2011. A devastating 16-year period after Clinton’s list fell in stark contrast to a glory-filled 16 years pre-executive order.

Photo: Referi

América de Cali were crowned domestic champions eight times during their heyday, but their inability to attract and retain the very best players proved fatal in the decline of the club. As their capacity for money laundering diminished, so did the presence of the narco-terrorists and their drug-fueled financial backing.

A Refereeing Display that Cost a Life

It was second nature for the head honchos of Colombia’s drug-fueled underbelly to be in competition. Fighting for territories, trafficking routes, respect, and now, football. Pablo Escobar began the cartel-football trend in the 1970’s, forming close ties with two local clubs, Atlético Nacional and Independiente Medellín. Both clubs began to flourish financially, although Escobar didn’t officially undertake any duties within the club, unlike América de Cali’s cartel owner.

In 1989, top-of-the-table América De Cali met third-placed Independiente Medellín, both of which were firmly aware that cartel money was sustaining each other’s efforts on the field. Both sets of ‘owners’ earmarked the fixture in hopes of getting the upper hand on their boardroom rivals. The country’s bragging rights were up for grabs, as the Orejuela brothers took on Escobar.

The 90 minutes would play out to a 0-0 draw, as both nets remained impenetrable. However, by the game’s end, Pablo had seen enough. For a man who was so accustomed to getting his way, several of the referee’s unfavorable decisions rendered him furious.

Like many, Escobar and fellow cartel members would often gamble on the outcomes of football matches, and it was reported that the referee’s perceived wrongdoing cost the Medellín Cartel a substantial fee.

Rumours and Escobar’s paranoia swirled post-game, as many speculated whether or not the Cali Cartel had bribed the referee before kick-off. This seemed a reasonable scenario for Escobar, who himself had offered money to referees in the past for them to look the other way and reward them with favorable results.

Álvaro Ortega completed the game as directed by Colombia’s footballing body, and packed away his whistle, black uniform and his boots, never to return to a football match again. The referee, like a rose between two cocaine-charged thorns, would be murdered that very evening.

Photo: Opinión Caribe

News of the killing spread throughout the world, drawing the attention of international powers, who asked for retribution for the sport in Colombia as a whole. The retribution they yearned for was certainly reciprocated in Colombia, but speaking out against a narco-organisation was a death sentence in the era of Escobar.

Many Italian football writers were of the view that Colombia should be erased from the upcoming 1990 FIFA World Cup, of which Italy were due to host. With pressure from within and away from football, a meeting between FIFA and CONMEBOL culminated in the cancellation of Colombia’s top flight for the remainder of the 1989/90 season.

Cameroon would later send Colombia’s national side packing from Italy in the Round of 16.

The Gentleman’s Final Word

A year on from the death of Colombia’s most infamous drug kingpin, Pablo Escobar’s unpredictable hometown is still riddled with violence and uncertainty. A 1994 murder outside of a Medellín nightclub is merely an everyday occurrence to frequenting locals. The spotlight shines brightly on this particular tragedy, however.

The captain of Colombia’s final World Cup game five days earlier, lay on the ground with six bullets in his back.

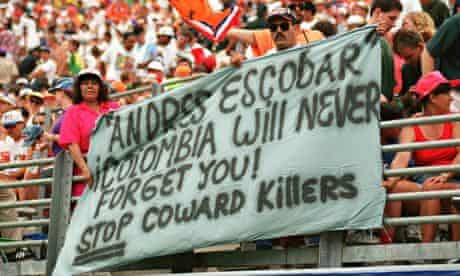

Photo: All Rise Films

Nicknamed ‘El Caballero del Fútbol’, the gentleman of football, Andrés Escobar plays his last game for Colombia in Pasadena, California. His life is snatched from him in the blink of an eye; his upcoming wedding missing half of its act.

The centre-back’s fatal mistake came in his country’s 1994 FIFA World Cup group fixture against the hosts of the tournament. Half an hour into the game with the score tied at 0-0; the USA switches the ball from right to left and proceeded to surge towards Colombia’s penalty area. Thirty yards from goal and to the left of the box, a cross is lashed into the area, in hopes of a willing recipient. Escobar’s outstretched leg closes the door on the ball’s path to the striker.

The ball’s course thereafter would rock Colombia and South American football to its core. Óscar Córdoba, Colombia’s goalkeeper, can only watch as the ball coasts past him into his net. The opening own goal of the game goes in favor of the United States, before Escobar’s side mustered up a consolation goal late on.

Credit: AFP / Getty

Colombia whimpered to last place in Group A, opening with the tournament with a 3-1 defeat to Romania. After losing to USA, Escobar oversaw a 2-0 victory over Roy Hodgson’s Switzerland in their final game. In a now chilling letter printed in Bogotá’s El Tiempo newspaper, Andrés Escobar penned what was his final public engagement to those accustomed to watching him lead Colombia’s national side.

“Life doesn’t end here, we have to go on. Life cannot end here. No matter how difficult, we must stand back up. We only have two options: either allow anger to paralyse us and the violence continues, or we overcome and try our best to help others.

It’s our choice. Let us please maintain respect. My warmest regards to everyone. It’s been a most amazing and rare experience. We’ll see each other again soon because life does not end here.”

Photo: Romeo Gacad / AFP / Getty

Faustino Asprilla’s Unwanted Cold Caller

Only three years on from the killing of Escobar, a nation still tries to shake an ever-present heinous crime from their memories. Colombia pits their wits against a plucky Paraguayan team, as they look to qualify for the competition which ended in such despair for them last time out.

Paraguay’s free-scoring goalkeeper, José Luis Chilavert, and Colombia’s Faustino Asprilla see red after 81 minutes. A fight ensues between the pair, resulting in both men receiving their marching orders and a penalty awarded to Colombia.

Photo: AFP

The spot-kick is dispatched, but unfortunately for Colombia, the Paraguayans claim a winner late into the game to make it 2-1. The lack of Asprilla’s presence and ability to register a reply, in addition to the 90 minutes worth of hard-done-by emotion, was enough to leave a nation incensed.

In a documentary released nearly 10 years after the heated fixture, Asprilla spoke of an alarming phone-call. It came on the evening of the game, whilst he sat in his hotel room.

A Colombian hitman spoke through the telephone seeking Asprilla’s blessing. The hitman wanted the green light from Newcastle’s very own marksman, to allow him to murder the hot-headed goalscoring shot stopper. Asprilla recalls asking the man if he was crazy, as he continued to explain that he would ruin Colombian football forever: “What happens on the pitch stays there.”

There would be no attempt on Chilavert’s life, but it was still a clear reminder that Colombia’s cartel-fuelled troubles still threatened to spill over into football.

The Peanut Men and their Horror

19-year-old Manuel Cortez, the only survivor, speaks to authorities whilst covered in blood. The teenager had spent the past two weeks with his neck chained to a tree in the baking hot sun. His teammates now slain, and their bullet-perforated bodies scattered throughout Venezuela.

Photo: La Opinión

Los Maniceros, or ‘the peanut men’ in English, were an amateur Colombian football team made up of friends. Away from their beloved hobby of playing football, the team sold peanuts on the Colombia-Venezuela border to make ends meet.

In 2009, Los Maniceros arrived for a football match in Táchira, Venezuela, a football match that would never finish. Instead, the quaint mountainous region bordering Colombia would become the scene of a group abduction.

Aware of the individuals playing, the murderous ‘Los Ñatos’ gang beckoned the players to them by their names whilst they stood on the football pitch. Los Maniceros were thrown into the back of vans and were never seen again.

Photo: EFE

Cortez attributed the horrors he had witnessed to an armed fraction of the National Liberation Army. The ELN (Ejército De Liberación Nacional, ELN) are a radical left-wing group founded in the 1960’s that still exists to this day, encompassing up to 3,000 members. The rationale behind the targeted killings remain unknown.

Colombian football has endured its darkest day. Its resurgence, away from the roots of narco-finances, can be mirrored in América de Cali’s phoenix-like rise from the ashes. Once competing for honours at the dizzying heights of Colombian football, controversy and U.S.-backed sanctions brought the club to its knees.

But no matter how many lives are lost, no matter how many bullets are fired, and no matter how many communities are torn apart at the seam, life, somehow, does go on. After a five-year spell in the second tier, Cali returned to the Categoría Primeria A in 2016. Last season, under the management of Alexandre Guimarães, Los Diablos Rojos won their 14th league title on December 7.

Photo: Luis Robayo / AFP / Getty

But no matter how hard they try, the stain of blood on Colombian football will never be wiped off completely.

By: Sam Ingram

Featured Image: Gabriel Fraga