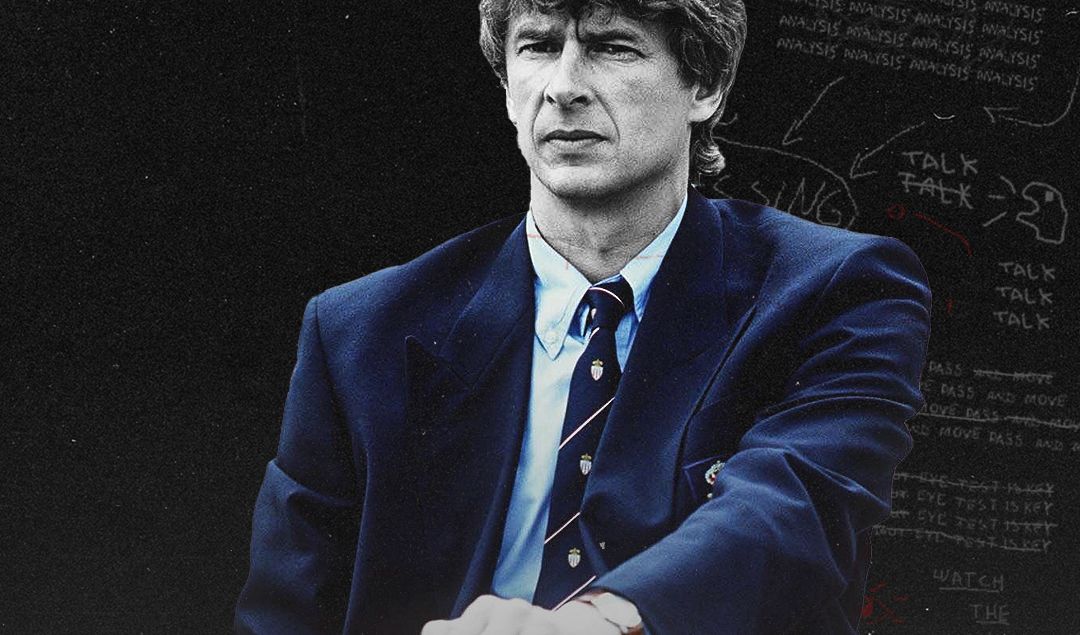

The Making of Arsène Wenger

Arsène Wenger is one of the most revered men in football. Not only is he a brilliant manager, he’s also a motivator, a teacher, a confidant and an eternal student of the beautiful game. Nevertheless, his final years at Arsenal were marred by everyone in the footballing world having an opinion on whether he should still be at the helm of the North London club, and that often eclipses his true greatness.

At his best, he was only challenged by the great Sir Alex Ferguson, but even at his worst, he was still the classy gentleman football learned to appreciate. His last days at the club where he earned much of his reputation didn’t go as he would’ve hoped, but that shouldn’t darken a great career.

For the Strasbourg native, it all started at home. After ending his playing career there, he began coaching the club’s junior teams and soon after that, he joined Cannes as the assistant to Jean-Marc Guillou. In charge of bringing in information about their opponents and collecting data, Wenger did a fine job in collating an analysis of who Cannes were set to play and that impressed the boardroom at Nancy, where he was appointed as the Head Coach in 1984.

On a tight budget and an average playing squad, Wenger was given a difficult task, but he made the most of what he had and combined that with his own tactical and vocational acumen to succeed according to standards. At Nancy, he also displayed the first instances of the methods that made his career so successful.

He would introduce new training methods that would see several players switch from their actual positions in order to maximise their potential, and arrange camps at high-altitude locations such the famous ski resort of Val Thorens and even the French Alps.

Perhaps most importantly and more strikingly, though, were the changes in the players’ diets. The manager hired a dietician to assist him and that would improve his players’ fitness and avoid injuries. These were revolutionary changes for a small football club and it resulted in relative success.

Nancy would finish 12th in Wenger’s first season in charge, but soon after that, they would sell some of their most important players. That would mean that a relegation play-off was required to sustain their Ligue 1 status for the following season which they also won. But the squad kept on becoming thinner as the boardroom aimed at keeping the club afloat and finances available to Wenger were becoming tighter.

The Four Best Players to Play for Both Arsenal and Tottenham

In his third and final season in charge, Nancy were finally demoted to Ligue 2, but Wenger’s reputation was still intact – he had overachieved considering the resources he had and as a result, Monaco would ask him to lead this exciting outfit.

At Monaco, Wenger was taking over a side that finished fifth in the previous season and at the time, this seemed like the perfect match. A talented, yet underachieving side was going to be handled by a meticulous and overachieving manager – the partnership was destined to work out.

Upon his arrival, Wenger already had his transfer targets in mind and within weeks of getting started, his squad was already far better than what he had inherited from his predecessor. Three players joined him immediately: Mark Hateley, a forward of supreme aerial prowess; Glenn Hoddle, one of England’s most interesting talents and Patrick Battiston, a free addition that could prove to be crucial.

But it wasn’t the additions or the players that Wenger had at his disposal that caught the eye in Monaco. It was the change in training regimes, the alternative diets and the increase in technical improvement. Wenger carried his old habits of changing players’ diets to improve their fitness and at Monaco, having learned more, he would introduce rice and pasta dishes to help his players perform better.

Riccardo Calafiori: What Can He Provide to Arsenal’s Defense?

In addition to that, he would host long meetings – often lasting up to 45 minutes – discussing his plans and strategies for the next game, and this would change training sessions accordingly. Change was in the works, and the results would follow.

After seismic alterations, Monaco would go on to win the Ligue 1 title by six points – a feat not many people expected. Wenger was a manager coming from a club that had just been relegated, and even the most optimistic of fans would hardly have expected him to have such a huge impact in such a short time.

As often seen later in his career, he would set up his team to emphasise upon their strengths in defence, mostly playing a 4-4-2 formation, with one of the forwards dropping deeper in midfield and playing just behind the striker in order to create a 4-2-3-1, thus, relying on the qualities of his wingers.

Another key, underrated aspect of Wenger’s success was his smart scouting and shrewd actions in the transfer market. Hately, Hoddle and Battiston were excellent signings, proving to be important in the title-winning season, and Wenger’s excellence in the market would show frequently during his time with Monaco – especially in the following season when he signed Liberian forward George Weah. Coming in from a nation that had little to no footballing exposure and from a league that was nowhere near as competitive as the highest competitions in Europe, the end result would show that this would be a masterstroke from the manager.

Arsenal’s Nearly Season: Disrupting the Backline, ‘That’ Trip to Dubai and Breaking Records

In the following campaign, his challenge would be to retain the Ligue 1 title they surprisingly won, and his biggest challengers would be big-spending Marseille. With an all-star side that included the likes of Didier Deschamps, Chris Waddle, Rudi Voller and Jean-Pierre Papin amongst a whole host of superstars, they would be a tough task to overcome. And in addition to that, there would be frequent blows between Wenger and Marseille President Bernard Tapie, which would often end in a violent war of words.

No matter how well or how significantly Monaco improved, Wenger’s team would finish behind Marseille and Paris Saint-Germain in the following season. They also reached the final of the Coupe de France, once again losing to their league rivals Marseille in a thrilling match that finished 4-3. Revenge for that would be taken in the next year, albeit in the Coupe de la Ligue, which they won through a last-minute winner.

The Marseille dominance would continue into the following year. Monaco would finish third once again, but this time, it would be Bordeaux that would finish as runners-up as injuries to key players and ageing talents would often hinder Wenger’s side.

Amidst the changes, there would be a great rise of younger players amongst the Monaco set-up as Emmanuel Petit would be integrated into the squad, while Weah’s versatility would be used to the maximum as he would frequently be used on the wings in addition to his primary role of playing as a forward. Despite failing to add any trophies, the future looked bright for the club based on the personnel that was available to them.

Over the next two years, Monaco and Wenger would achieve great success on the continental scene. First, as a result of winning the Coupe de la Ligue, they would take part in the European Cup Winners’ Cup, losing to Werder Bremen in the final. And in 1994, they would make the semi-finals of the Champions League, losing to eventual winners’ AC Milan on the way. Although they didn’t yield any silverware, this was a great achievement for Monaco as their young, improving team proved that they could cut it at the highest stage.

That fantastic Champions League run would be Wenger’s last significant success with the famous red-and-white of Monaco. Bayern Munich were interested in acquiring the Frenchman’s services, but his current employers weren’t too pleased with that and refused to let their manager depart. Perhaps, as a result of the distraction, Monaco made a poor start to the season and after just over a month into the new campaign, they let go of one of their finest managers with the team fighting with relegation.

Shortly after leaving his homeland, Wenger’s next job would be on the other side of the world in Japan. Having taken part in a series of football-related conferences organised by FIFA in the United Arab Emirates, Wenger would meet with representatives of Nagoya Grampus Eight and their chief sponsors Toyota and after weeks of negotiations, he agreed to take the reins at the clubs in December 1994, four months before the new season began in the Land of the Rising Sun.

With the Far Eastern country improving in status as a footballing nation after several high-profile players including Zico, Dunga and Gary Lineker moved there, Wenger saw the potential to get himself back up and running. However, the team he took over, Nagoya, weren’t all that great. They had struggled to succeed in recent seasons, often settling for mid-table finishes. Ideally, after the success Wenger enjoyed in France, this was a job that he shouldn’t have taken, but seeing the eternal persistence of the man, this isn’t much of a surprise.

The Price of Success | The Perilous Youth Pathway At Arsenal

To Japan, he took Boro Primorac – the man that exposed the corruption in French football – as his assistant and his work would begin from there. After a slow start to the season, Wenger changed his approach.

He would spend time in press conferences questioning his team’s desire and on-pitch management in the hope of helping his team understand their mistakes rather than seek help from their manager. This proved to be the right approach as his team rallied, choosing to motivate themselves rather than sulk under the pressure.

Between May and the end of the season in November, they would lose just 11 out of 39 games, which was a great return, seeing as they lost nine out of their first 13. This would help them finish as runners-up in the league, but there would be silverware coming to them by the end of the season. The Emperor’s Cup would be won, beating Sanfrecce Hiroshima in the final, in what would be one of two trophies the Frenchman won in Japan.

After a strong end to the campaign, hope was high that a title would finally arrive at Nagoya. Once again, it would be the hero from the previous season Dragan Stojković who would spearhead their charge, but they would fall just short. Nagoya added the Japanese Super Cup, but in the league, they would fall just short of champions Kashima Antlers. With Wenger’s reputation enhancing once again, he would leave Japan for Arsenal without having won anything noteworthy, but his changes were important.

Perhaps if he had stayed, he would’ve been a legend in Asian football. At a time when it was on the rise, he played a part in its off-pitch improvement and those results were exhibited on the field. But due to his departure, his true legend was there to be seen. For over two decades at Arsenal, he would achieve great success and inspire excellent teams, becoming one of the greatest and most revered coaches of the modern day.

By: Karan Tejwani

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / Bongarts

This article was originally published on Football Chronicle.