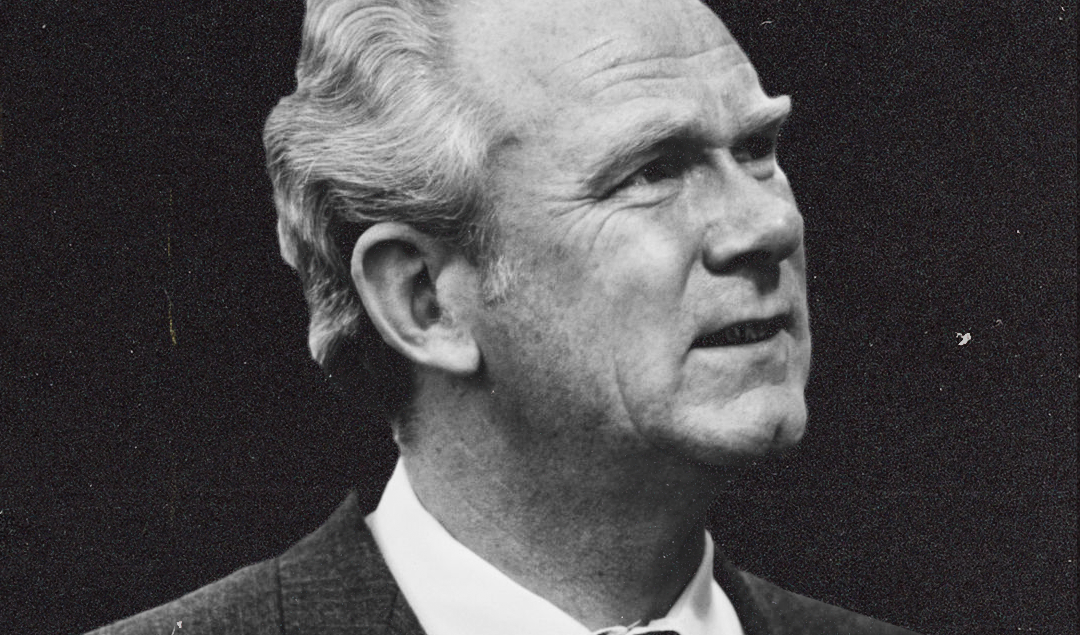

Valeriy Lobanovskyi: Football’s Forgotten Pioneer

When we look at how Barcelona, Manchester City, Ajax, even Sheffield United play, our minds invariably go back to the Total Football of Rinus Michels and Johan Cruyff. The high press, positional rotations and pursuit of space preached by the Ajax, Barcelona and the Dutch national sides of the 1970s have come to define how the modern game is played.

At the same time, however, some 1,200 miles east of Amsterdam, a Ukrainian coach by the name of Valeriy Lobanovskyi was preaching total football, but in a wholly 21st Century way. Utilising science and statistical analysis, he was streets ahead of the Dutch masters.

From 1968 to 2002, his teachings on the game created a footballing dynasty at Dynamo Kyiv and helped pave the way for the modern era. And yet, when we search our minds for the greatest managers in the sport’s history, we barely remember his name. This is the story of the forgotten pioneer of modern football.

Photo: Getty

Lobanovskyi’s teams played in a style that was quintessentially Total Football. His Dynamo Kyiv side defended as a team, relying on aggressive pressing with the furthest forward player being the first line of defence. On the ball, they broke with pace, exploiting the space their defensive tactics created.

As a result, Kyiv were a truly formidable side winning 8 Soviet titles, 6 Soviet Cups, 5 Ukrainian National League titles, 2 European Cup Winners’ Cups and 1 European Super Cup. His first victories in the European Cup Winners’ Cup and Super Cup, coming as early as 1975, marked the first European trophies won by an Eastern European team. But it is his reliance on science and statistics that separates his legacy from the Cruyff and co.

Lobanovskyi and Anatoly Zelentsov collected innumerable amounts of statistics on their players and opponents to create mathematical models that defined how his players trained and played. So when Lobanovskyi said that, “a team that commits errors in no more than 15 to 18% of its acts is unbeatable,” he wasn’t guessing.

To minimise this error percentage, his players were worked incredibly hard in training. The pair’s mathematical models were utilized to construct rigorous training sessions in order to make Dynamo’s players as fit as they possibly could be. They also needed to know how to read the game collectively, meaning they had to know where to pass before they got the ball. As such, his players were required to memorise set plays as if they were American footballers.

In his book, Football Against the Enemy, Simon Kuper recounts the time he met Zelentsov, the scientist who played a key role in devising Lobanovskyi’s revolution. At the time of Kuper’s writing, Lobanovskyi was managing in the Middle East, but Zelentsov was still working at Dynamo and took the time to explain his and his partner’s ‘science of football.’

Photo: Keith Lyons / Clyde Street

Zelentsov even granted Kuper access to Dynamo’s video analysis room, where the most recent match was being played across a screen divided into nine sections.

Statistics were collected that measured the performance of each player in each section. These were then analysed by Lobanovskyi and Zelentsov to find out the best player combinations across the pitch. To this end, Dynamo players were given rankings on “‘intensity’, ‘activity’, ‘error rate’, ‘effectivity’ (‘absolute’ and ‘relative’) and ‘realization’, and awarded a final mark computed to the third decimal point.”

Cruyff, on the other hand, was vastly differently. Under the tutelage of Michels, the first great exponent to take Total Football outside of the Netherlands, Cruyff became symbolic of the success of the philosophy as both a player and coach. However, the Dutchman was unnerved by the influence of computers and statistics in football.

So deep was his dislike of their influence that, when discussing the differences between his and Louis van Gaal’s rigid management style, Cruyff stated, “I want individuals to think for themselves and take the decision on the pitch that is best for the situation…I don’t have anything against computers, but you judge football players intuitively and with your heart.”

Cruyff’s influence on modern football is in many ways immeasurable, but his aversion to the input of computers casts a slight shadow over his otherwise spotless legacy. Lobanovskyi and Zelentsov, however, were pioneering sports science decades before it became mainstream. Lobanovskyi’s commitment to the philosophy was absolute, and if you delve into his background, it becomes clearer as to why this was the case.

At the age of 22, Lobanovskyi was still a player. In 1961, he had helped guide Dynamo Kyiv to their first Supreme League title – the former top Soviet league. But, after his victory, he was asked why he looked so sad. His response?

“Yes, we have won the league, but so what? Sometimes we played badly. We just got more points than other teams who played worse than us. I can’t accept your praise as there are no grounds for it.”

His drive for perfection was obvious, but he was also suffering a conflict over styles. During the 1960s, Lobanovskyi had spent time training as a heating engineer in an era when the Soviet Union lead the world in scientific advancement. His education in such a time instilled in him a pragmatic and empirical approach to everything in his life. But his time as a flashy and joyous winger complicated things, causing him to consider the aesthetics of the football he dreamed of creating.

But his path was decided when he first met Zelentsov, who at the time was a statistician and Dean of the Dnipropetrovsk Institute of Physical Sciences. Encouraged by his early conversations with Zelentsov, Lobanovskyi realised that in breaking down a game of football into its simplest possible form – two systems made up of 11 players – one fact became unavoidable: the efficiency of a team was greater than the efficiency of the sum of players that comprise it.

In essence, a team working together to a set plan will achieve more than relying on individual talent. To Lobanovskyi, this presented him with the opportunity to apply broad reaching cybernetic techniques to football. He set out to find ways to get the best out of various player combinations that would improve the team as a whole, and at Dynamo Kyiv, that’s exactly what he did.

Photo: Getty

To me, this is why Lobanovskyi moves into his own realm of influence. While both he and Cruyff preached the benefits of pressing your opponent into the optimal condition, it was Lobanovskyi who did so with the infallible logic of statistics. Today, stats tell the story of each game, colour debates, and influence the future of whole football clubs. An entire cottage industry has since sprung up in the collection and dissemination of these numbers alone.

Anyone who has watched football long enough will have seen this transition occur. 20 years ago, it was more than enough to simply know how much time a team had the ball or how many corners they played for. Now, additions like GPS tracking vests are an essential part of understanding player and team performances.

With the possible exception of former Leeds manager Don Revie, there has been no other manager before the modern era to have invested such responsibility in numbers. But Lobanovskyi used it to develop a style of football that now dominates the game. And yet, we barely remember his name.

Perhaps it is the fault of technology, with the type of equipment he regularly used, not at the disposal of his contemporaries. In our current data-driven world, we can appreciate how he was miles ahead of his time – the fact I’m writing this article on a marvel of modern technology is testament to that – but in his own time, the rest of the world might have needed to catch up. Or perhaps it is because of the state he represented.

Photo: Vasily Artyushenko / ZN.UA

At the height of the Cold War, it would have been easier to pin the ‘great pioneer of football’ badge on an enigmatic Dutchman rather than on a man who managed the Soviet Union twice. But no matter what, his success and eventual legacy cannot be overstated.

As well as working miracles at Dynamo Kyiv, his two stints in charge of the USSR saw him reach the final of Euro 1988 – ironically losing to the Netherlands – and winning the bronze medal at the 1976 Olympics. In all, he won 33 trophies as a coach, making him the second most decorated manager of all time, behind only Sir Alex Ferguson.

It is unclear whether his strict disciplinarian tendencies would be accepted today. According to Kuper, when Lobanovskyi once saw one of his players drunk, “he set him to a work as a groundsman for five months, and then sold him to a lesser club.” His approach to transfers may also have shown signs of age in an era of free movement and player power – it was his desire to cherry pick the best talent within the Soviet Union before selling them off for immense profit in Western Europe.

Nevertheless, his legacy on the pitch is undeniable. With players expected to be as versatile as the game itself, relying on lighting quick breaks and a united defensive responsibility – all the while being continually guided by statistics – Lobanovskyi’s vision of football is an almost exact mirror of today’s.

Photo: Stringer / Russia

Such was his commitment to the game that he even died on the job, suffering a heart attack in 2002 as Dynamo Kyiv played FC Metalurh Zaporizhzhya. A minute’s silence was held at that year’s Champions League final in his honour, but since then, his name has largely fallen out of regular football parlance. Hopefully this piece can help reaffirm his legacy and cause us to look at football in our times and realise his fingerprints are everywhere.

As the inscription on his tombstone reads, “we are alive as long as we are remembered.”

By: Ben Miles

Photo: @GabFoligno