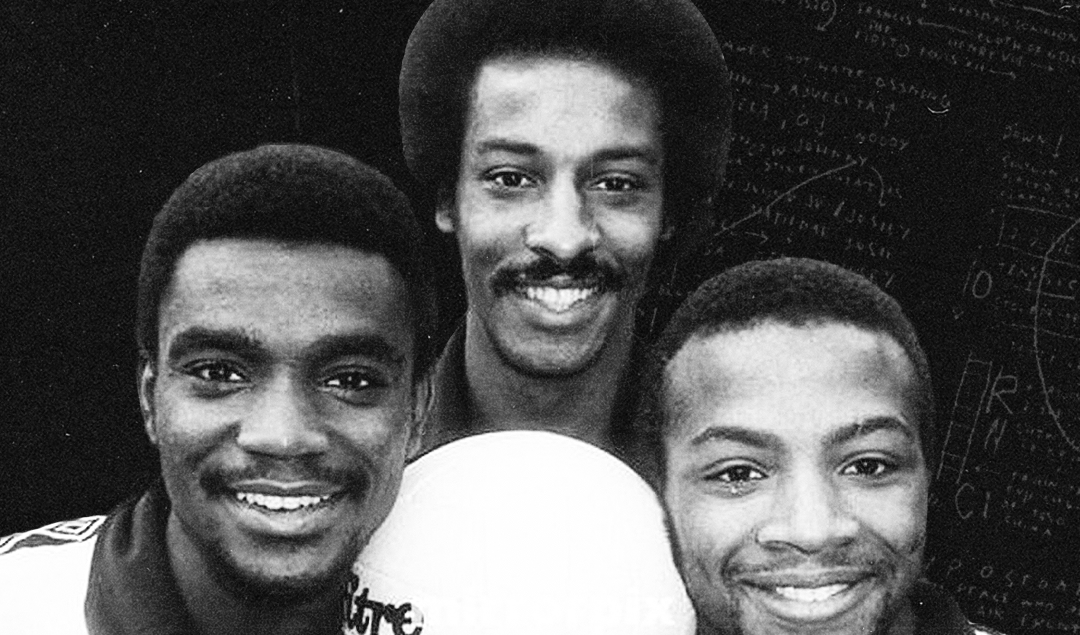

West Bromwich Albion’s Three Degrees: Pioneers in English Football

At a time where the topic of racism in sport is more prevalent than ever before, it’s worth remembering some of the heroes who made football more acceptable and open than it was several decades ago.

While the game is still marred by racism, even in England, it would’ve been worse had it not been for West Bromwich Albion and their renowned Three Degrees of Cyrille Regis, Laurie Cunningham and Brendon Batson, who paved the way for more black players to take up football and silenced racists with their incredible performances on a weekly basis.

The club from the English Midlands may not have the most illustrious history, but this part of it stands out more than most. In the 1978/79 season, with these three at their best, The Baggies, led by manager Ron Atkinson, became the first English club to consistently field three black players in their fixtures – something that may seem normal now, but something that was unheard of at the time.

At a period where racism was rife as England struggled to come to terms with the rise of multiculturalism, West Brom were a revolutionary club, and the abuse they faced was silenced by the brilliance of these three footballers.

Regis, a star born out of scuffles, grew up in French Guiana. Struggling to make ends meet, his family moved to London when he was just five years old, and it was here that his love affair with football would begin.

A trained electrician and an excellent player at non-league level, clubs in London refused to offer him a pro contract on the basis of race, but West Brom scout Ronnie Allen was keen on his ability, offering to pay his wages at the club himself. The club took the chance and ended up with a gem of a footballer amongst their ranks.

This was during a time where coaches believed black players didn’t have the necessary skillset or lacked the tactical outlook to handle the English game, but Regis’ signing and subsequent success proved them all wrong. It was his background as an electrician that also made him more relatable – football was a game for the people, a game for all classes, and his upbringing made him all the more likable.

Photo: The Guardian

He was joined by Cunningham, a dazzling winger who was a beloved figure at the Hawthorns for his ability to beat a man with ease and create chances at free will. The son of a Jamaican race-horse jockey, Cunningham began his career at Leyton Orient before becoming a vital player for The Baggies.

Such was his impact over the years at the club that in 1979, he became the first ever English player to join Real Madrid, further dismissing silly claims that black players weren’t gifted. Injuries troubled him in the Spanish capital, but he made a point.

Last to join and complete the trio was defender Brendon Batson, who was born in Grenada and moved to England at the age of six, via a brief spell in Trinidad and Tobago. Playing as a full-back, he first joined Arsenal as a youngster, becoming their first-ever black player, but rarely got time on the pitch before finally finding his feet in football at Cambridge United.

Four successful years at the club led to a move to West Brom, where he would connect with his two iconic team-mates, and establish a legacy whose presence would be vital for generations that followed.

Photo: Rex

Although the trio weren’t the first black players to play professional football in England, they were amongst the first to garner that much attention – mostly in a negative way. The team’s coach, Atkinson, was often hounded to not field them in their games, with fans sending him hate mail on a regular basis.

Other white players – including a budding Bryan Robson – would often be asked how they ‘tolerated’ playing with the triplet, but they didn’t care. They were crucial in this movement as they stood up for their team-mates, being all the more motivated to silence the racists.

Rising at the time was the National Front, a collection of extreme-right groups who actively took part in political and societal issues. They were, perhaps, the worst of the lot. Batson spoke about the issue:

“We’d get off the coach at away matches and the National Front would be right there in your face. In those days, we didn’t have security and we’d have to run the gauntlet. We’d get to the players’ entrance and there’d be spit on my jacket or Cyrille’s shirt.

It was a sign of the times. I don’t recall making a big hue and cry about it. We coped. It wasn’t a new phenomenon to us.”

And if the jeering and banana-tossing at games was bad, the death threats were even worse. Unfortunately, they were the norm for these players. Just before making his England debut, Regis received some appalling “fan mail” which read: “If you put your foot on our Wembley turf, you’ll get one of these through your knees.” The letter was accompanied with a bullet, which Regis kept.

Photo: Getty

He would make five senior appearances for the national team, and just like Cunningham’s tally of six, it was far too few. Maybe if they played in the current era, that number could well have reached double figures, because they most certainly had the talent. Amongst all that, it’s worth remembering how good they were on the pitch as well. Regis is regarded as one of the club’s greatest players, and with good reason too.

Although he never won any major trophies, his performances in big matches, such as those against Manchester United in the 1978 FA Cup will always be remembered. The Baggies were close to winning the league in 1979 with massive help from the trio, but could only finish third, behind champions Liverpool and Nottingham Forest.

Even looking at videos of him show the grace and composure he had; the way in which he glided through teams was wonderful to see. Such was his talent that Johan Cruyff wished to sign him for Ajax when Marco van Basten left for Milan, while the legendary Saint-Étienne teams which dominated French football in the ‘70s were keen on signing him too.

Cunningham’s move to Real Madrid at the age of 23 speaks for itself. After winning a league and cup double in his first season in Spain, knee issues hampered his career, but even after that, he would get chances at major outfits like Manchester United and Marseille. His love for dance was exemplified out on the field – defenders could hardly catch up to him – and at his best, he was widely regarded as one of the most entertaining footballers of that era.

Photo: Bob Thomas / Getty

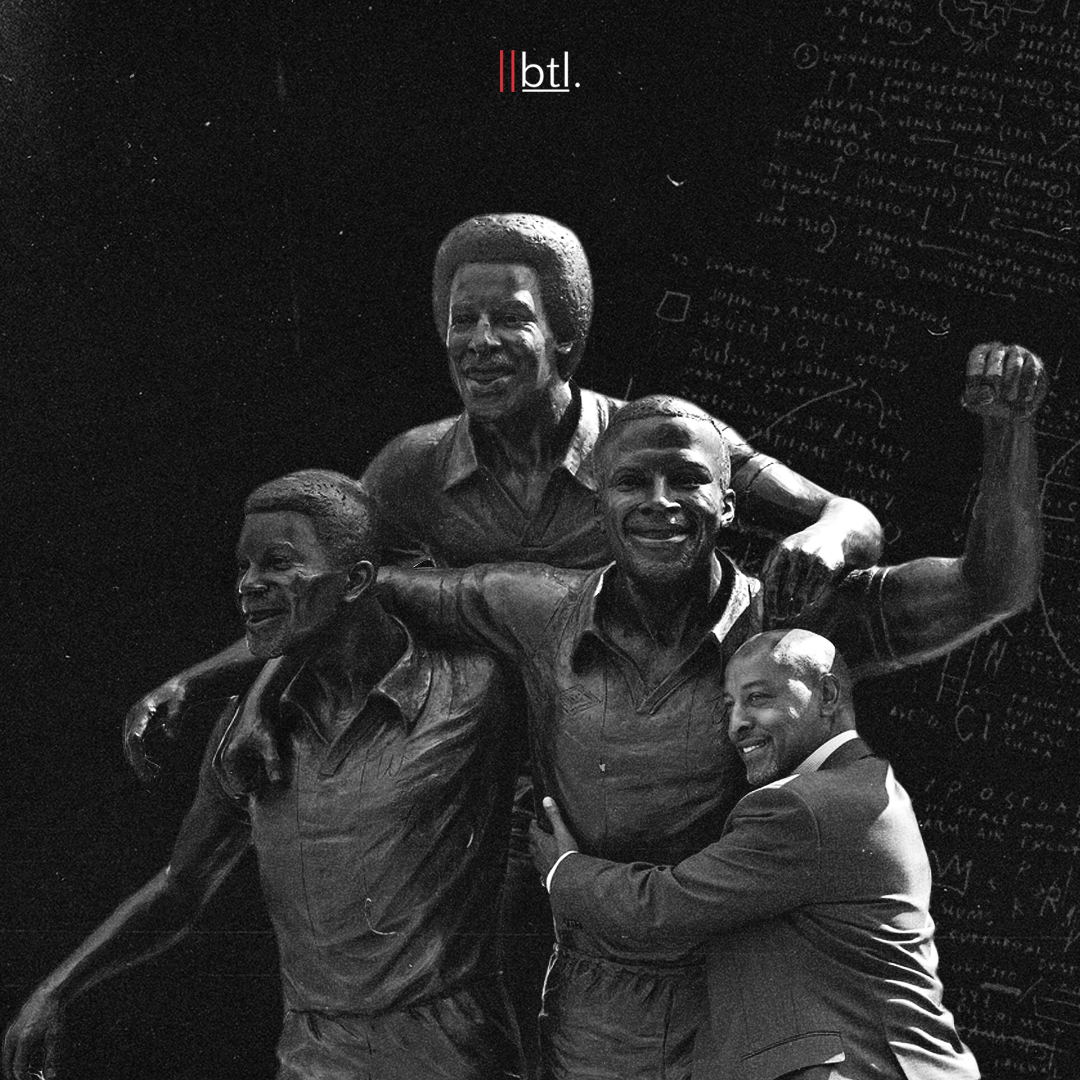

Batson, meanwhile, spent the last four years of his playing career at West Brom before his own injury issues forced him to call time on his career. After retiring from the game, he continued his fight for an equal game by landing a senior position at the Players Football Association.

The trio were nicknamed as The Three Degrees by the West Brom faithful, a name that arose from the American vocal group of the same name. Sadly, only one of the three, Batson, is currently alive. Cunningham was killed in a car crash in Madrid at the age of 33; Regis died of a heart attack in 2018.

Both their memories as well as Batson’s legacy is immortalized outside West Brom’s stadium in the form of a statue – the epitome of the legacy they left behind, not just for them or the club, but for black footballers of that era as well as the ones that followed. They made nearly 500 appearances for West Brom, and are rightfully considered pioneers in the English game.

People talk about wanting gifted hardmen on their teams – players who will jump into tackles, take a knock, go in for aerial duels and cover every blade of grass in every game, but the real hardmen are the likes of Regis, Cunningham and Batson who faced disgusting amounts of racism, abuse and rejection in every game they played in England.

From monkey chants to bananas thrown at them, unspeakable words to harrowing gestures, they went into games with a smile, did what they did best and rarely let the pressure get to them. Not only were they great at football, they opened pathways for the future, encouraging more black athletes to take up sport at a time when it was life-threatening. The Three Degrees are heroes in the English game, and their legacy is eternal.

By: Karan Tejwani

Featured Image: @GabFoligno