Football in Conflict Zones

It is just past 6 am in Ukraine on the morning of August 23. The Donbass Arena, home to Ukrainian football champions Shakhtar Donetsk, was just bombed twice as the conflict between national forces and pro-Russian separatists hit a peak.

As it is not a match day, the 52,000-capacity stadium was empty and hence there were no casualties, but the $425 million venue took significant damage. Because of the violence Shakhtar had to relocate to Lviv in the western region of the country, five hours away from Donetsk.

Photo: BBC

This was five years ago. Because of the uncertainty, Shakhtar has since moved again, this time to Ukraine’s capital Kiev, with the club setting up their training facilities in the city in 2017. However, the side, who are the current champions of Ukraine, play their games at the Metalist Stadium in Kharkiv in northeast Ukraine.

“Every time when you play at home, you must go by flight,” current Assistant Manager and former Shakhtar player, Darijo Srna said in an interview. Football and conflict are intricately tied, and while the sport can resolve disputes, it can also crumble under their weight.

Football and Security State Politics

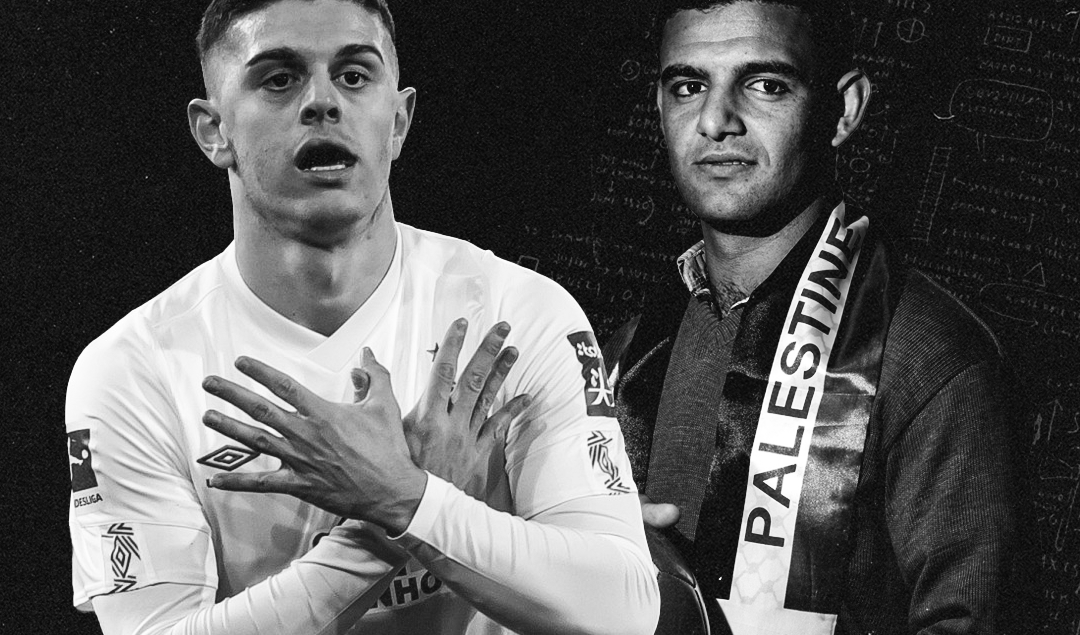

24-year old Mahmoud Wadi currently plays for Egyptian side Al Masry, having signed for the Port Said club in the summer of 2018. His journey there, however, was a difficult one.

Born in Khan Yunis in the southern part of the Gaza Strip, the Palestinian international faced the geopolitical pressures that restrict football in the country: random security checks, travel bans and being separated from teammates after being arbitrarily detained by security forces at the Gazan border.

When Wadi got his first international call-up in 2014, Israel’s Operation Protective Edge was in full swing, meaning the player’s career hung in the balance. “I had to train, but I didn’t care about the war,” Wadi said of the time.

Photo: Media Sport

Before Wadi, Mahmoud Sarsak was one of the biggest stars in the Gaza Strip. In 2009, the former Palestine international was detained by Israeli forces without any charges.

Sarsak, accused of involvement with the extremist group Islamic Jihad, denied the allegations and went on a three-month hunger strike to protest his detention. He was released in 2012. However, following his three-year detention, Sarsak’s footballing career came to a premature end.

“Israel not only robbed me of my career and my passion, but also my freedom,” Sarsak wrote.

The Palestine national football team, first recognized by FIFA in 1998, has faced similar restrictions in building a squad. The Gaza Strip and the West Bank have hosted some of the region’s best players. However, while they were eligible for the national side, these players were held back by the security forces.

As a result, “when they [Palestine] were first building a team, they only had about 10 or 12 players at a time,” James Montague, an independent journalist and author said.

Conflict and Politics Clash in European Football

At the 2018 World Cup in Russia, football and politics clashed in a different manner when Switzerland played Serbia in the Group E game on 22 June.

Granit Xhaka did it after his equalizing goal early in the second half. Xherdan Shaqiri did it after his last-gasp winner. The gesture: the two-handed eagle, a celebration both players brought out upon scoring in that game. The significance: an expression of Albanian and Kosovar identity.

Photo: Gonzalo Fuentes / Reuters

Both players have roots in Kosovo, as does midfielder Valon Behrami. While Xhaka and Shaqiri said their celebrations were not politically charged and claimed the gesture was out of emotion, the pair were fined 10,000 francs for “unsporting behavior,” and avoided bans relating to political messaging.

Meanwhile, others, such as Kosovo international Milot Rashica, have also celebrated with the double eagle, albeit mostly in league games and not on an international stage. However, Rashica, who currently plays for Bundesliga outfit Werder Bremen, has not received the scrutiny Xhaka and Shaqiri did.

Still, Rashica’s national side Kosovo offers a look into the former Yugoslav states, where following the violent conflicts of the 1990s, football was a powerful tool in the nation-building and rebuilding process, according to Montague. In this regard, sport was entangled with politics.

Having declared independence from Serbia in 2008, only FIFA and UEFA have recognized Kosovo as a state and while the Eastern European nation is a member of both organizations, other bodies and groups, including Russia, Serbia and the United Nations do not recognize the country.

Nevertheless, the national side’s recognition is symbolic for the greater “aim of recognition as an equal nation among others,” Montague concluded.

Football in Iran: National Unity, Political Activism and the Pursuit of Rights

In Iran, football, as the most popular sport, is uniquely important.

“Our national volleyball team won the Under-21 tournament and no one cared. But when we won against Morocco in the World Cup last year, all the people were in the streets celebrating,” Vania Ashoorian, an Iranian first-year student at Carnegie Mellon University in Qatar said.

With the side securing their first win in 20 years in 2018, the national team “has us all proud,” she added. However, in addition to being a source of unity in Iran, football is a battleground for political activism.

Tractor Sazi is an Iranian football club based in the city of Tabriz, in the East Azerbaijan Province in northwest Iran. When the side played Esteghlal FC at the Azadi Stadium in the capital Tehran in February, Sazi’s fans chanted “Death to the dictator!” a popular phrase at the anti-government demonstrations in 2017.

Photo: MEHR News Agency / Vahid Abdi

For Sazi’s fans, who are primarily of Azerbaijani and Turkic heritage and constitute a minority group, the expression holds still greater significance. In the case of the Tabriz side, “a football club, which for many might seem depoliticized space, became a site of political resistance,” a recent journal article claimed.

According to Vahid Rashidi, the article’s author, because the more traditional forms of street or university demonstrations have faced severe crackdowns, football emerged as a new platform for protest. Over the last few seasons, Tractor Sazi and Tehran-based Esteghlal have built a feverish rivalry, second only to the derby between Esteghlal and Persepolis in the capital city.

As a club that represents the Turkic-Azeri minority, Sazi are in a position to counter Esteghlal, who are viewed as a pro-government side given their indirect associations with the monarchy and following the 1979 revolution, their ties to the Islamic government who subsequently gained control of the club.

Meanwhile, for Sazi and its fans, the fight for rights and recognition has been difficult. When they played Esteghlal in August 2018, police attacked and even arrested Sazi’s fans. Ashoorian, who is from Tehran, was critical of the Tabriz-based club and its fans.

“It’s toxic. It’s great to love and support your club, but injuring the other team’s fans and throwing stuff at the players on the field is just not acceptable,” she said. However, there is insufficient information to indicate confirmed violence on the part of Sazi’s fans.

In Iran, football has another stumbling block: spectatorship. Since 1979, women have been barred from entering stadiums when men are playing. In a 2022 World Cup qualifying game in October, that changed, as women attended a game in the capital city Tehran for the first time in four decades.

Photo: AFP

However, female fans in the country cannot watch men’s league games in the stadiums. As a result, Ashoorian, who supports Tehran’s Persepolis FC, has not been able to attend her team’s matches. “I usually go to cafes and restaurants to watch matches with friends,” she said.

Unlike the stadiums, these venues are not segregated, so everyone can enjoy the game, she explained. For Ashoorian, and others like her, the mere act of watching football is an expression of identity.

Football and Geopolitics Collide in the Middle East

In the build-up to the 24th edition of the Gulf Cup in Qatar, questions were raised about the role of geopolitics considering the ongoing blockade against Qatar. For one, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates’ call to reverse a previous decision and participate in the tournament received wide attention.

Furthermore, when the Saudi Arabia national team traveled to Doha for the competition, they did so in the first direct flight from Riyadh in two years. Even before a ball had been kicked, the themes of football and conflict were already engaging. When Qatar took on UAE on 2 December, the themes of the blockade emerged again, except in a different context – fans on social media poked fun at the Emirati team, who had been beaten by the hosts for a second time this year.

Qatar’s semifinal tie against Saudi Arabia three days later had a more serious undertone, as the opposition had won each of their previous three games. Despite this, Qatari fans’ excitement was palpable. “People were cheering, holding Qatar’s flag or wearing a scarf,” Mariam Fahad Kamal, a Qatari student who attended the match said.

Even when Saudi scored, Qatar’s fans were passionate and did not give up until the final whistle, she noted. In contrast, before Qatar headed to the AFC Asian Cup in January, there were concerns among locals about how their team would travel to UAE and how they would be received, Kamal said.

In addition, Qatar played the tournament without their national fans, who could not attend the competition because of the blockade. In solidarity, Omani fans stood with Qatar and supported the team during the Asian Cup.

Photo: Al Jazeera

When the Qatari team returned to Doha after securing the Asian Cup trophy, “everyone was celebrating, everyone was happy,” Kamal added. The national team’s triumph was a sort of revival that united the population, from locals and expatriates to even tourists, she explained.

Football has served as an arena for “contestations, identity claims, conflicts and violence,” Mahfoud Amara, a scholar and author wrote in his book Sport, Politics and Society in the Arab World. Similarly, the sport has the potential to transform her country to a more modern and unified state, Kamal concluded.

Interactive map: The global story of football and conflict. https://uploads.knightlab.com/storymapjs/c9fdaace81e35e90dade9826e6ef933c/the-global-story-of-football-and-conflict/index.html

By: Manan Bhavnani

Featured Image: @GabFoligno