Wrexham AFC in the 21st Century and the Path to Its Acquisition by Ryan Reynolds and Rob McElhenney: Part 1

This article is Part 1 of a series about Wrexham Association Football Club; you can read the second part of this series here.

Wrexham Association Football Club was formed in October 1864. This makes the football club the oldest in Wales; and the third oldest professional club in the World (after Notts County and Stoke City). It is located in Wrexham, Wales. This is in the north of Wales. With a population of 65,692 as of 2011, it’s the most populated town in northern Wales and fourth-highest in the entire country.

“It is closer to 100,000 now but yeah, it is the largest town in the North,” says James Kelly, a Wrexham fan who has been to hundreds of games. Having become a trade hub in previous centuries, the town was at the forefront of the Industrial Revolution from the 18th century onwards. This made it a hotspot for mining; brewing, and the production of iron and leather. These industries then went into decline in the 1970s and ‘80s, with most commercial hubs now in the southern part of Wales.

Wrexham A.F.C currently play in the National League, having dropped out of the Football League at the end of the 2007/08 season. Prior to this, the club had been in the Football League for 87 years. While in the Football league, the Welsh team had built a reputation for beating larger sides in cup competitions, with their 2-1 Third Round victory over Arsenal in 1992 cementing this status, and creating a memory still recalled by their fans till date.

The only northern Welsh side competing in the English football system, the Red Dragons were a firmly established Football League side going into the 21st Century. However, the new century brought with it new problems.

Who Owned Wrexham Before Rob and Ryan

Wrexham’s off-the-field ownership problems began primarily in the 21st century. Before the new century began, the club had been owned and run by Pryce Griffiths. He was a local businessman who sold newspapers wholesale across northern Wales. He joined the board of directors in 1977, and was the chairman of Wrexham by 1984. He left the role in 1986 but returned two years later, saving the club from bankruptcy by becoming majority shareholder.

Pryce passed away on November 11, 2020. He is fondly remembered for personal moments such as being a local fan as a child and taking part in the construction of the team’s stadium, as well as developing the stadium and opening a training facility for the staff while he served as director. A stand at the stadium is named after Griffiths. ”Everyone liked him, he was a good owner,” says Kelly, a board member of the Wrexham Supporters Trust. “He did mess the club up in terms of selling it to the next owners, though.”

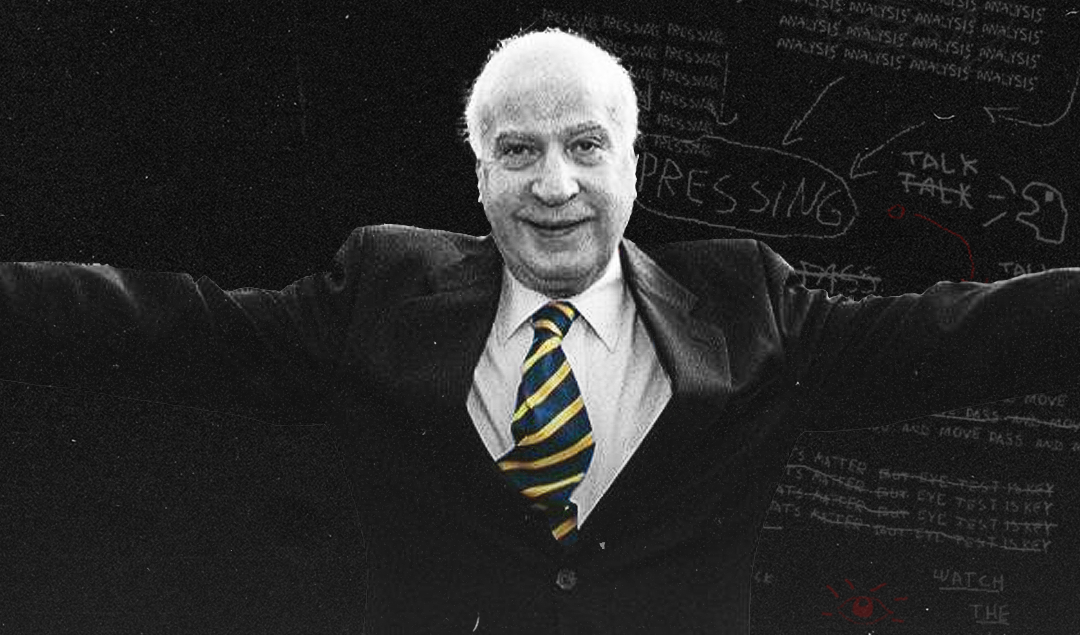

Photo: The Leader

While the late, long-serving chairman is remembered fondly, the individuals he sold the club to are certainly not. In fact, they are quite reviled. Griffiths retired in 2002 after health concerns and sold 78% of Wrexham to property developer Alexander Hamilton for 50,000 pounds via company Memorvale ltd. As soon as Hamilton came into the picture, issues weren’t too far behind him. The first of many problems was Mark Guterman.

Guterman was ostensibly the new majority shareholder as of June 2002, but it was later revealed he was simply a façade to hide the real owner, Hamilton (both Guterman and Hamilton were directors at Memorvale). Guterman had also been chairman of Chester City, Wrexham’s arch-rivals. Okay. Probably not the best idea for the chairman of your sworn enemies to replace your beloved retiring chairman; and said the retiring chairman should have done his due diligence.

He had been at the helm when Chester City went into administration in 1999, and had a history of putting businesses on the fast lane to liquidation. Now Guterman was in charge of Wrexham, promising a hotel, offices, and conference rooms in the stadium’s vicinity.

I imagine some readers are asking themselves, how could this deal be approved by the Football League with such a shady character in the mix? Well, the “fit and proper person test” was not introduced until 2004, and the test only applied to directors anyway. In other words, this would be approved either way. After all, neither Hamilton nor Guterman broke the rules required to be directors, while no framework existed to vet owners.

Hamilton and Guterman had signed a secret agreement in 2002, agreeing to equal control while they realized the maximum gain from the property assets of Wrexham, keeping all the profits for themselves. With no checks and balances, both men began the process of stripping the club of its assets under the guise of commercial development.

Racecourse Ground (Wrexham’s stadium, and the World’s oldest international football ground that still hosts international matches to date) was bought from then-owners Marston’s Brewery in 2002 for 300,000 pounds. Ownership of the stadium was immediately transferred over to Crucialmove, Hamilton’s company. Hamilton then paid another 300,000 pounds via Guterman in 2003, canceling the club’s 125-year lease agreement at the stadium and giving Wrexham 12 months to find a new ground to play in.

Suffice to say, fans and staff of the Red Dragons were raging and illustrated this with protests at Wrexham home games. During this period, the team was interchanging between League One (then the Second Division) and League Two (then the Third Division) quite frequently. By 2004, Guterman had resigned, selling his ‘financial interests’ to Hamilton and citing personal reasons for his decision.

Hamilton then became chairman of Wrexham, façade seemingly now unnecessary. He threatened to kick the club out of Racecourse Ground unless compensation for the football team and stadium was offered to him. This caused a crisis at the Welsh club; with fans organizing meetings with directors, rumors emerging of having to share a stadium with rivals Chester and the Inland Revenue demanding unpaid taxes to the tune of 900,000 pounds all within the year 2004. The unpaid taxes were due to then-chairman Guterman not paying the club’s income taxes for the past year, a surprise to absolutely no one.

Wrexham Supporters Trust (they’ll be discussed soon) received a notice to leave Racecourse Ground in July 2004, this became public in September. The Trust then placed two bids to buy the club in November 2004, Hamilton rejected both bids. By November, both Hamilton and managing director John Reames had resigned, with the tax authorities petitioning for a winding-up order which would shut the club down. Hamilton was still a majority shareholder after his resignation but stopped servicing any of the club’s debt after resigning.

The winding-up petition was initially granted but eventually lifted on 17 November 2004. A month later, the club was saved due to a legal hearing deciding Wrexham should be put into administration. The Robins had finally left the clutches of incompetent ownership or at least one kind of it. The administrators did due diligence on the previous owners’ dealings and determined both Guterman and Hamilton had acted in bad faith by not acting in the club’s best interests despite being in positions of authority within Wrexham.

The administrators sued Crucialmove, Hamilton’s company in June 2005 in order to get Wrexham’s stadium back into the club’s possession. Hamilton (pictured below) and Guterman fell out around this time, and their aforementioned secret agreement became public as a result. This was the basis used by administrators to attempt a summary judgment in court, which the judge granted in October 2005.

Photo: North Wales Live

The appeal was also won in March 2006, upholding the initial court ruling both parties had used the positions of chairman and director to enrich themselves. “Hamilton and Guterman are viewed as the lowest of the low by the Wrexham community to this day,” says Kelly, a Wrexham fan since he was eight. “They tried to end our football club. Wrexham are actually one of the main reasons the fit and proper persons test was introduced.”

‘The Daves’ must get a special mention. Both Dave Griffiths and Dave Bennett were directors on the board at the time and prevented Hamilton from succeeding by not voting for his plan to redevelop the Racecourse Ground and move Wrexham to the outskirts of their own town. Administration meant the club were given a 10-point penalty for the 2004/05 season, which led to relegation to League Two.

It was the lesser of two evils truly, as liquidation had been a very real possibility under the previous owners. The team valiantly won the Football League Trophy in 2005, defeating Southend United 2-0 and giving the fans something to smile about after a morbid few years. With the corrupt owners out through the back door, the hope was that the Dragons could find owners with the club’s best interests at heart and kick on from there.

Around the time of the appeal court judgment, an exclusivity agreement was struck between the appointed administrators and a consortium of local businessmen led by car dealership owner and former Wrexham director, Neville Dickens. The deal was backed by the Football League in June 2006 and signed in August of that year, taking Wrexham out of administration for the first time since 2004.

Dickens brought forward a 10-point plan which included clearing the debts of about 4.5 million pounds, issuing shares to fans, and developing the stadium further to increase long-term income. The consortium planned on selling the club after 18months, with Wrexham in a more secure financial position by then. Dickens’ major partner in the consortium was Geoff Moss, a businessman from Chester. The Supporters Trust backed the deal as well.

These plans were eventually seen to be mere words after a few years, with no concrete steps taken to clear the debt by 2008. Plans were made with North East Wales Institute, a school, to build student flats on the stadium grounds, but NEWI backed out after waiting in vain for a scheme to commit to. Dickens had also used a leveraged buyout to buy Wrexham, with a 2.5m pound loan from then-Liverpool shareholder Steve Morgan.

I don’t need to be Warren Buffett to let you know using debt to buy a club isn’t the best way to start the process of clearing said club’s debt. Dickens ended up selling his 50% stake in Wrexham to Moss in 2008 while staying on as senior vice-president. Dickens claimed this was to avoid a conflict of interest with his nearby garage and the land he owns surrounding Racecourse Ground; as the development of the stadium was being planned. Moss then became chairman.

Geoff Moss ended up building the student accommodations via his Wrexham Village holding company. He bought the land from Wrexham A.F.C for 6million pounds in June 2009. This cleared 5m pounds of the club’s debt to Moss, who had been loaning the club money (with interest occasionally). By 2011, Moss was still owed 5.3million pounds by Wrexham via his company, Wrexham Village. The club was losing money annually as if it was routine.

From March ’09 to June ’10, Wrexham had losses totaling 1.2million pounds. In 2008, Wrexham had wages of 1.99m pounds financed by revenue totaling 1.895m pounds. During this period, Moss then shadily separated Racecourse Ground stadium and the training ground from the club (here we go again) and transferred it over to Wrexham Village company. Eventually, the club went up for sale in 2011. By this point, 115 people ranging from caterers and coaches to players weren’t getting paid salaries.

Moss buying the land for his student accommodations also ensured no profits would go back into the club, breaking one of the promises his consortium agreed to. “Moss is not particularly liked by the fans, though some do respect him,” Kelly says. “He sold that land to himself under the guise of using the profits to redevelop one of the stands.

Photo: Paul Ellis / AFP via Getty Images

The stand never got renovated, despite the student accommodation he built bringing in 12 to 13million pounds apparently.” Racecourse stadium and the training facility were sold to Glyndwr University for 1.8million pounds. Glyndwr is located in Wrexham, and the deal allowed the club to continue to use both structures.

With their beloved club up for sale once again in 2011, fans of Wrexham saw this as an opportunity to finally treat the club right, as only its community could. The Wrexham Supporters Trust bought the club on 12 December 2011, when the deal was officially ratified by the Football League after being accepted by Moss and co-owner Ian Roberts in September. The deal meant Wrexham was completely owned by supporters.

“The WST was formed in the early 21st century in a more informal manner and under a different name,” says Kelly, a WST member since 2012. “The acquisition of Wrexham AFC really formalized the organization though.” By this time, Wrexham had already established itself as a National league side for four seasons. 2 teams get promoted from the 23 available in this league, and only first place is automatic. It would be a struggle to get back to the Football League, or so the thought went.

That season, despite the rife takeover rumors all season, Wrexham was in 1st place by the time ownership had changed hands. By the end of the season, they finished 2nd, qualifying them for the conference playoffs along with the four teams below them.

The Red Dragons lost to Luton Town in the semi-finals but showcased their never-say-die attitude with a win at home in the second leg after losing the first. The next season they were at Wembley, winning the Football Association trophy in front of 35,000 supporters. They made the playoffs that season again but narrowly missed out on promotion with a 2-0 defeat to Newport County.

After a fantastic start to the ownership on the field, the WST ensured the debts of the club were cleared and built a viewing platform for the disabled at Racecourse Ground. The stadium was handed back to the club to operate by the university in 2016, as part of a 99-year lease agreement. It currently holds 10,771 people. The student flats still loom over the stadium, serving as a reminder of the past mistakes the club has had to face on the path to peace and prosperity. Little did they know, it was only the start of the joy that was to come.

By: Aanu Omorodion

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / The Leader