Tactical Analysis: Las Palmas 3-1 Valencia

Throughout the 2016/17 footballing season, there were many interesting matches. Many of these go relatively unnoticed in the chaos of the schedule and are neglected in terms of the depth they deserve. In a BTL exclusive feature, writer Ross Eaton (@boxtoboxcb) will be analysing a series of these intriguing football matches…

Two sides seemingly trapped in the monotonous mid-table round-up, the rather interesting sides of Quique Setien’s Union Deportiva Las Palmas and Voro’s Valencia met on a clash which could make a significant difference in terms of their league table finishes. The fluid positional play of Setien’s side would face a similarly pragmatic Valencia system.

Javi Varas was UDLP’s goalkeeper. Michel played as an attacking full-back on the right, Castellano pretty similar on the left. Lemos and Bigas were the CB’s. Vicente Gomez was based as the deepest of the midfielders, with Roque Mesa a slightly higher average position to his right. Montoro was the third central-midfielder. Momo played the game from the right wing position, with Kevin-Prince Boateng taking the centre-forward role. Jonathan Viera was the LW.

Valencia used a similar 4-3-3/4-2-3-1 type base shape. Diego Alves; Cancelo,Garay,Mangala and Gaya made up the back five. Parejo and Soler played as right and left 8’s. Enzo Perez played a slightly more advanced central-midfield role. Munir was Valencia right-forward, Nani the left. Santi Mina was the team’s number 9.

Pressing Movements on the Fluid Build-Up

As a key principle of Juego de Posicion, it was unsurprising to see Las Palmas place such emphasis on a clean, flowing build-up. Often finding emsleves in a very ambitious, positive shape in their first phase, the press they faced would have a large impact on their possessional game.

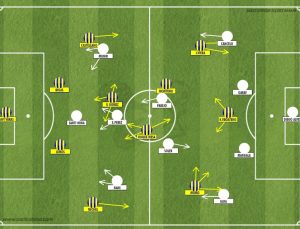

Initially positioning themselves in a 2-3-2-3, with the CB’s splitting wide into either halfspace and the full-backs pushing up onto a line with Vicente Gomez, UDLP were in a very wide shape, ideal for stretching and disorientating a high press.

Rather than dropping into vacated centre-back space like many pivots in similar structures do, Vicente Gomez simply made small, threatening movements towards this space, to encourage a Valencia press to mark him. This was usually done so by Valencia’s ball-near midfielder, typically Enzo Perez, as he was most advanced of the three. This defensive action had to be done by Valencia, otherwise Vicente.G would simply receive the ball from Javi Varas unopposed, giving him valuable time and space to make a progressional pass from phase one.

When Valencia marked Vicente.G, he would move into the left halfspace, vacating the central space just in front of the centre-back position. From an initially higher position, Roque Mesa would now make a long dropping movement, either onto the same line as Vicente.G, or perhaps even deeper, right into the central space in the backline. Due to the the midfielder’s initially high position away from the ball, it was unlikely that Valencia had a great defensive focus on him before this movement, as in that moment his position was unthreatening. This meant when he made the movement, he was often unmarked. If the movement was made quickly enough, he may even have a one or two second window where he could receive the ball from Javi Varas unopposed.

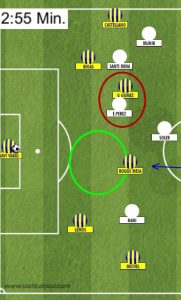

Very successful in the early stages of the game, with Roque Mesa dropping unopposed into a free space between his CB’s, Valencia eventually adapted their pressing in order to prevent this pattern frequently occurring, and causing their first and second lines of pressure significant problems.

The main change was rather than Santi Mina choosing a CB to mark whilst Javi Varas had the ball, he would position himself centrally, dropping the man-orientation, and shield the centre from passes or movements into this space. This meant Mesa had to attempt to find an open angle of pass either side Mina, in a much smaller space. For obvious reasons, this decreased how often and easily he could receive the ball from Javi Varas in the first phase.

In terms of preventing the CB’s receiving the ball, which was important due to both their strong ability in phase one, Munir and Nani positioned themselves between their near-CB and FB. This meant although the CB’s appeared open to receive, as soon as the pass to them was made, Munir/Nani would spring into a press, blocking their escape route of FB in the process. The positioning of Munir and Nani was important, as if they were too close to the full-back, the CB’s could receive with a second to make a progressional pass. If too close to CB, Javi Varas played high passes into the full-backs who moved slightly higher.

The adaption of Valencia’s pressing quite early in the game was a positive for them, as it greatly limited the originally free-flowing and very effective Las Palmas build-up and progression from phase one.

Overload. Adjustment and Unbalancing. Exploitation.

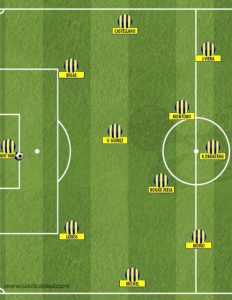

With common inverted movements from wingers Momo and Jonathan Viera both when dribbling and when teammates where in possession, it was unsurprising that Las Palmas’ main method for breaking the last line was a pattern involving a winger moving inside. The pattern used featured a number of key Juego de Posicion concepts, which were largely effective in achieving the objective of this pattern.

With a well spread (vertically and horizontally) Las Palmas occupied a wide range of zones on the field. One common problem from this type of ‘stretched’ positional play is disconnection, due to the large distances between players. However, UDLP avoided this common issue in a number of ways. Most importantly was their use of fluid movements, from one zone into another. This often meant stepping into a zone already occupied by a teammate, to create an overload. This was the beginning of a frequent and key Las Palmas attacking pattern.

Starting from typical 9 and right-wing positions respectively, Kevin-Prince Boateng and Momo would drift from these original positions into the right halfspace as possession looked ready to progress, often dropping slightly deeper into build-up as well. Roque Mesa would also sometimes move into this same space. As this overload occurred in the right halfspace, Valencia were forced to adjust, and bring defenders to this area to avoid UDLP taking full advantage of their numerical superiority in this space. As Valencia adjusted, they became unbalanced and lost control in the areas they vacated to gain defensive access. The primary area Las Palmas opened up here was the right wing, with Gaya, Valencia’s LB, following Momo into the right halfspace. Whilst still possessing numerical superiority in the right halfspace, Las Palmas would play a strong vertical pass into Boateng. He would then use his strength and back-to-goal ability to combine with those facing him. As this combination took place, Michel would begin a specifically timed run up the open right wing. When the moment was correct, Boateng would ideally play a lay-off pass to Momo, who would then feed out a diagonal pass to Michel, who should receive on the move without breaking stride. By doing so, he should be able to attack the space up the right wing before Valencia could recover and defend here.

From this pattern, Las Palmas actually found great success numerous times in breaking Valencia’s last defensive line. This was often done so through the gap found between LCB-LB, to Michel, who altered between straight and diagonal runs. Though his diagonal runs took him closer to Valencia’s goal, it also took him closer to Valencia’s defenders, which with his indecisiveness and uncomfort in an unfamiliar area for him, was rather costly a number of times. When the right-back stuck to the wing and played low crosses or cutbacks, UDLP looked very threatening.

Conclusion

In a game consisting of so many chances, it was surprising that there was just four goals. Both sides frontmen played very variable roles in the final third, which was rather effective considering the high number of crosses from full-backs in the match. In and around the box, both sides looked extremely vulnerable defensively, and strong in attack. The centre of the field saw not onto some great collective play, but some terrific individual performances from a midfield dominated by Spaniards, making the quality of positional play unsurprising.