Attacking in a Front Five vs. a 4-4-2

Attacking with a front five is becoming more and more common in modern football. This is largely because it is paramount to positional play. Positional play is predicated on the occupation of specific spaces and zones, and attacking with a front five facilitates occupation of the five vertical corridors associated with positional play (two wide spaces, half-spaces, central space).

This has been evident at Chelsea since the arrival of German manager Thomas Tuchel. The implementation of the 3-4-2-1 formation allows for perhaps the most natural occupation of the five vertical lanes (wing-backs in wide zones, wide forwards in half-spaces, centre-forward in central zone). Tuchel has previously explained that his teams essentially attack with five and defend with five which manifests his structured outlook on positional play.

Tactical Analysis: The First Weeks of Thomas Tuchel’s Chelsea

This explanation seems overly simplistic given the complex, multidimensional nature of football, however, it certainly highlighted his belief in occupying the five vertical lanes in order to achieve desirable positional play. This article will analyse how attacking in a front five can dismantle a 4-4-2, while using Chelsea’s magnificent performance at Crystal Palace as a template.

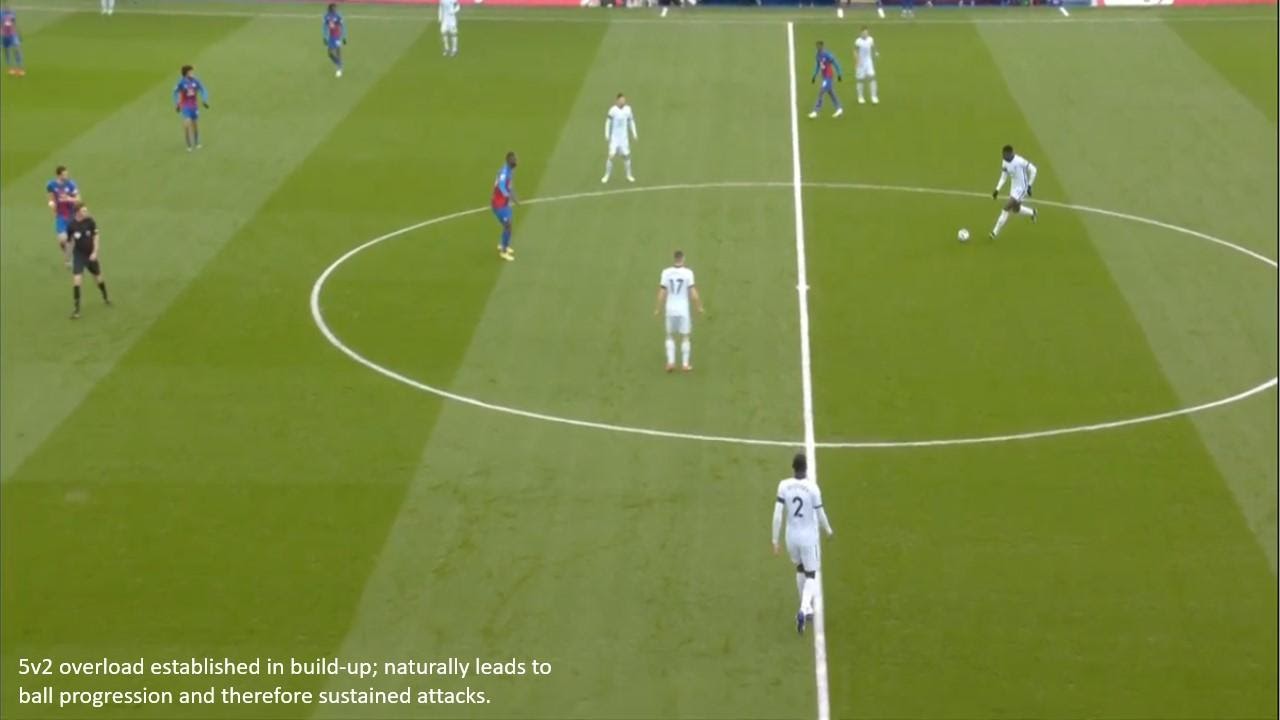

Firstly, in alignment with Tuchel’s ‘defend with five, attack with five’ proposition, proposition, the structure typically allows a significant overload to be established in the first phase. Having five central players contribute to build-up (three centre-backs, double pivot in this case) usually allows the team in possession to create a 5v2 overload against the opposition’s forward line (assuming the opposition prioritise compactness rather than applying pressure further up).

Given the significance of the overload, this grants time and space for the deep players in possession, which can ultimately lead to ball progression into forwards, and therefore sustained attacks, which leads to the prevention of opposition chance creation.

This seems to be the prominent reason behind Chelsea’s defensive improvement since the arrival of Tuchel; the defensive improvement is manifested by the control they have in matches, which derives from their ability to sustain attacks and prevent the opposition from creating chances.

The role of César Azpilicueta specifically manifests a common theme throughout this article, and also Chelsea’s performances; buying time and space in possession. Since the arrival of Tuchel, the Chelsea captain has predominantly played at right centre-back, a position which is paramount for access to the half-spaces.

When Chelsea had deep, consolidated possession, i.e., around the half way line, against Crystal Palace, the objective seemed to be to find Azpilicueta in time and space. This was obtained through the double pivot’s (Jorginho and Mateo Kovačić) commitment to the left hand side in build up, which ultimately forced the opposition’s forward line to press and engage centrally rather than the wide centre-backs. This was supplemented by the wider positioning (horizontal stretching) of Azpilicueta.

These factors created time and space for the Spaniard upon reception, which essentially allowed him to progress the ball with ease. Time and space are the two elements in football which can expose the opposition’s lack of pressure/pitch coverage, and therefore, Chelsea were, and are frequently able to find their attackers between the lines, which can help form and establish relationships and understandings due to this repetition. This ultimately aids ball progression into the final third and can also impact offensive play in turn.

Attacking with a front a five against a (4)-4-2 essentially gives you an overload behind the opposition’s midfield and in front of the opposition’s defence. This means there is almost always a spare man, which is usually the far side wing-back (will be discussed later), however, this can sometimes be a more central player if the opposition fail to adequately shuttle across. This was prominent in Chelsea’s performance at Crystal Palace through central-striker Kai Havertz.

After central possession (with Chelsea central centre-back), Palace would shuttle across when the ball was released towards the wide centre-backs. The ball side wide midfielder and central midfielder would cover the vertical passes into the wide space and the half-space respectively, which in turn, typically opened central space when Palace failed to shuttle adequately. This often left Havertz free, who would drop into the space to aid ball progression. He often received unpressured due to the zonal restrictions applied to the Palace centre-backs.

The risks that the overload carries from a defensive perspective can be exacerbated via quick ball circulation and positional interchanges which can disrupt defensive organisation. Positional interchange can cause a defensive predicament, especially when the half-space player interchanges with the wing-back (half-space player moves wide, wing-back in possession carries inside).

This is because the opposition full-back is likely to continue to pressure the ball carrier (wing-back) and be dragged away from their wide area, and the ball side centre-back is unlikely to cover the wide area to mark the half-space player who has drifted wide due to zonal restrictions.

If the centre-back was to commit to man-orientation and move wide, a significant gap between the two centre-backs would appear which could easily be exploited. Hypothetically, this greater commitment to the ball side would exacerbate the potential of a switch.

Credit & Source: Metrica Sports

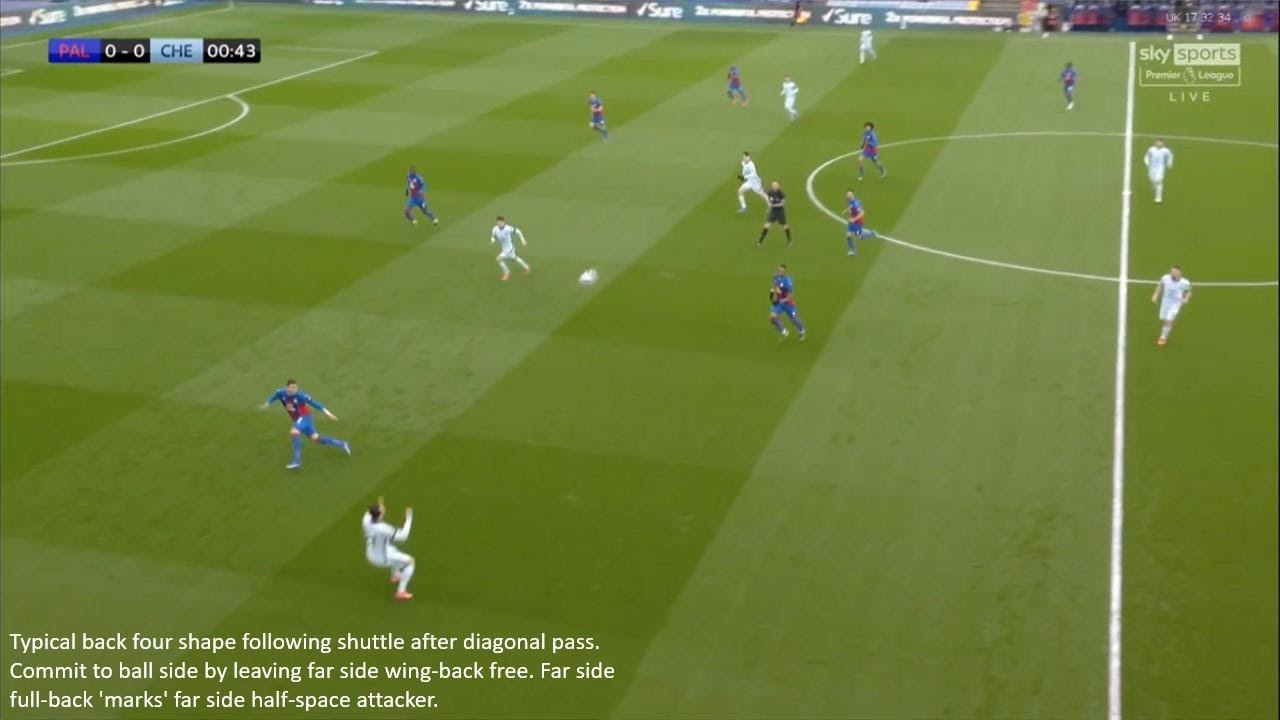

As the video shows, the positional interchange out wide (half-space player and wide player) created free space for Mount due to the zonal restrictions that centre-backs carry in a zonal 4-4-2 block. Switches can also be effective when attacking with five against a 4-4-2. In order to combat the 5v4 overload across the front line, the defensive team typically relies on shuttling across as a unit to cover adequate space horizontally.

This typically involves the ball side full-back applying pressure to the ball carrier when the ball is on one flank, with the opposite full-back tucked inside, leaving the offensive team’s far side wing-back free in space. Their position is viewed as less dangerous considering the distance to their ball. However, this is open to exploitation via quick switches over a long distance.

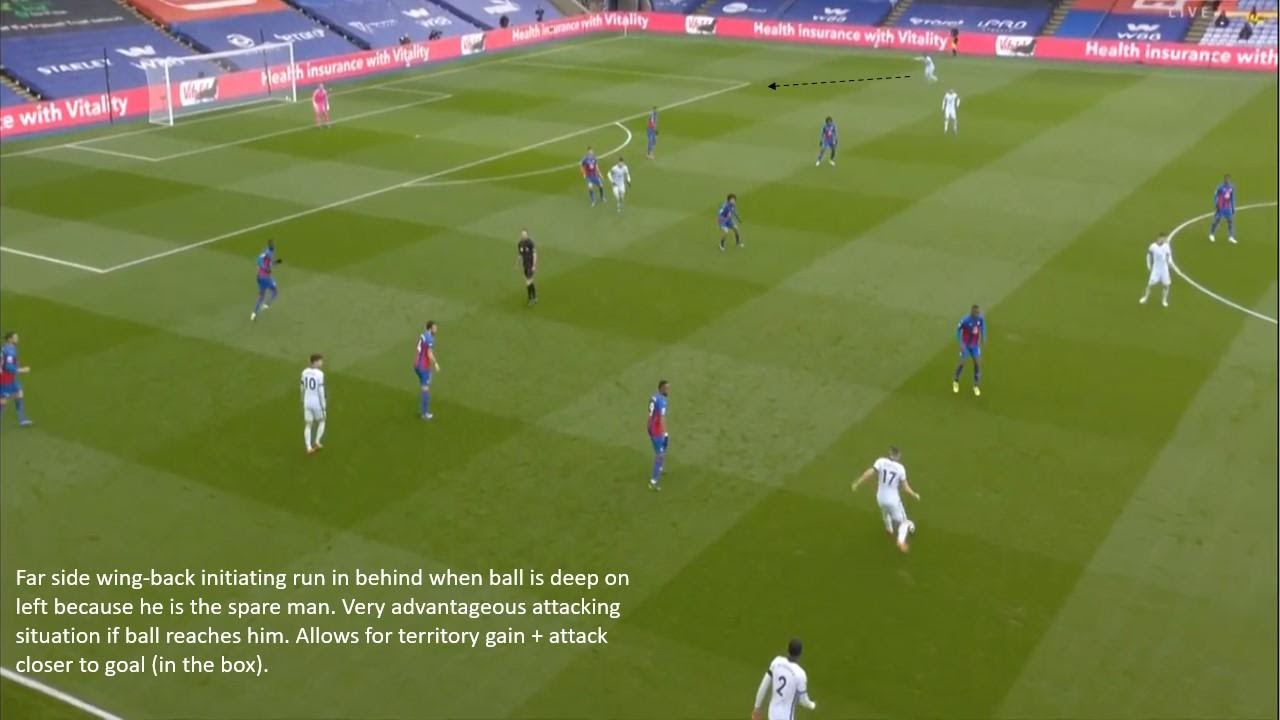

The role that the far side wing-back plays in initiating the switch is paramount to its success. Naturally, the wing-back can receive with time and space following a switch because the opposition’s shuttle essentially means he is the free man, however, it is more advantageous with vertical stretching (run in behind) in addition to horizontal stretching (maintaining width on the touchline).

The wing-back’s forward momentum can be important when initiating runs in behind the last defensive line because it essentially gives them a head start against the opposing defender. This is because the defender is reactive in this scenario; his movement completely depends on the movement of the wing-back, which ultimately grants the attacker more time and space upon reception, if the switch is accurate, because of the split-second where the attacker holds the initiative. Vertical stretching in this scenario can result in territory gain, and therefore more dangerous attacks upon reception out wide because the ball is closer to the goal.

Despite their potential, switches that require urgency in order to exploit the space on the far side are difficult to execute from a technical perspective. In order to maximise the potential advantages of horizontal and vertical stretching, you need players, typically deeper midfielders or defenders who can reliably pass over long distances on a consistent basis.

The space that the wing-back has to receive possession can be increased via an inside run by the far side half-space player. It is essentially used as a decoy run to drag the full-back into a narrow and deep position, thinking that they must track the run. However, this increases the distance between the opposition full-back and the eventual ball receiver following a switch and therefore, there is greater time and space for the wing-back to exploit the lack of coverage or pressure.

It seemed like this had been worked on previously when Chelsea took on Crystal Palace, specifically through Mason Mount, who showcased his intelligence and awareness of space creation by making this direct run in behind when deep possession is consolidated on the left. Again, this run is predicated on creating time and space for the eventual ball receiver in possession, a common principle under Tuchel. Chelsea’s second goal perfectly manifested the importance of switches in order to drag the opponent wide, force them to shuttle, and ultimately create and find gaps within their defensive structure.

Credit & Source: Metrica Sports

Quick ball circulation in deep areas is paramount to the use of the double pivot further up, and therefore establishing relationships with attackers. Moving the ball quickly essentially forces the opposition’s front two to work harder and become disjointed in trying to apply adequate pressure onto central players, which therefore creates space for receiving players. This results in the wide centre-backs having time and space in possession following the quick ball circulation, as usually, the opposition’s front two will opt to screen passes into the double pivot in the archetypal 3-2 build-up shape.

However, when the ball does go wide to the wide centre-backs, the centre-forwards struggle to impact the game from a defensive perspective. Against Palace, it was simple for Chelsea to follow this pattern: central centre-back -> Azpilicueta in time and space -> inside pass into Jorginho -> progress to attackers between the lines. This was frequently available because the centre-forwards could not shuttle across in time to block passing lanes into midfield as a result of the quick ball circulation across the backline.

Credit & Source: Metrica Sports

Therefore, this created a predicament for the Crystal Palace midfield. Should they step out and engage? Should they sit deep and remain compact but allow progression into the double pivot? Which passing lanes should they block?

This ultimately helped Chelsea progress the ball into dangerous zones. In the longer term, this ultimately encourages relationships to be established between the defensive five and the attacking five, due to the repetition and frequency of these patterns occurring; this is evident in the video below.

Credit & Source: Metrica Sports

The principle of passing to team-mate under pressure is also another prominent aspect of Tuchel’s Chelsea. It is more so a generic principle in possession, rather than one which can only be applied to this context (front 5 vs 4-4-2), however, it did help Chelsea dismantle Crystal Palace.

This aspect focuses more on attention to detail. It is difficult to find a team with greater attention to detail currently than Tuchel’s Chelsea, which impressive given the lack of time the German has had on the training ground with his team in this fixture congested season.

Credit & Source: Metrica Sports

The principle manifests a common theme throughout this article: buying time and space for the receiver. This is manifested by passing to a teammate under pressure in order to drag a marker away from the eventual receiver, which therefore creates more time and space upon reception. For these reasons, this principle largely depends on a third man (typically the ball receiver). This was extremely prominent in Chelsea’s performance at Crystal Palace.

Patterns like this are predicated on manipulating the defensive team to move closer to the ball, or to be attracted by the ball, only to move further away from the eventual receiver (Ayew moving further away from Rudiger in the case above). Passing into a zone, or into a player who is tightly marked, naturally results in the opponent jumping towards the ball in attempt to force difficult reception, however, with players that are comfortable under pressure, this can be dangerous as it can present space behind which can be exploited via quick passing.

Credit & Source: Metrica Sports

Backwards to go forwards is also more so a general principle rather than specific to this context, but Chelsea’s performance against Crystal Palace shows how useful it can be when attacking with a front five against a 4-4-2. The general idea behind the principle is essentially to lure the opposition forward and into a press, in order to open space further up the pitch which is open the exploration via quick combinations in deep areas under the intense press of the opponent.

Chelsea moved the ball backwards and also to one flank, which was crucial, because it creates greater amount of space for the far side wing-back in the event of a switch. The primary consequence is that baiting the opposition into a press by playing backwards and to one side forces them commit high up and aggressively to the ball side, which ultimately means their pitch coverage is open to exploitation via a quick switch of play to the opposite wing-back, due to the extent of their aggressive ball side press.

Credit & Source: Metrica Sports

Backwards to go forwards requires technical security under pressure, because it involves being able to maintain possession and progress the ball under an intense opposition press. It is important to remain composed under pressure.

This is likely to be the reason behind Chelsea’s ability to do so because their deep players (Centre-backs, double pivot) are extremely effective under pressure, and therefore have the ability to remain composed and progress the ball when the opponent presses high. This is paramount to the success of exploiting space in behind and out wide, which is prominent in this example.

Credit & Source: Metrica Sports

This is where the role of the wing-back is paramount to the team’s ability to switch play. They can stretch the pitch horizontally and vertically which grants the team an outlet when play becomes congested on one flank. Their positioning is paramount to the threat of a switch, because the wider they are, the greater time and space they will have in possession upon reception.

In summation, Chelsea’s performance at Crystal Palace perfectly manifested how attacking with a front five can dismantle a 4-4-2. As the amount of teams who attack in a front five continues to increase, this performance should act as a platform to build on. The established overload in the first phase was supplemented by quick ball circulation which allowed Chelsea to sustain attacks and control the game.

Then, their sharp passing under pressure, switches of play, positional interchanges and space creation methods were crucial to their wonderful attacking performance, in which, they secured a comfortable 4-1 away win.

By: Ollie Himsworth

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / Rob Newell – CameraSport