Creating a Qualitative Superiority: Sassuolo

A qualitative superiority refers to a situation, where instances of numerical equality are in real terms not equal. It can be used holistically as a complex way to describe the ‘better team on paper’ or is something more individualised within games, which is where I feel it has more analytic use.

Using the principle of not all situations of numerical equality being equal, teams attempt to manufacture positions where they can have their better players isolated as to exploit the circumstance of ‘real’ terms inequality. This article will analyse the method by which Sassuolo isolate their danger men in Jérémie Boga and Domenico Berardi, creating situations of qualitative superiority.

There is a general preference to show play down the left when building up as Boga in particular can often be effective at wriggling his way through multiple players and progressing via dribbling while Berardi is more end product-oriented; however, both players are capable in both regards which makes it a preference rather than limitation which makes any distinction barely noticeable.

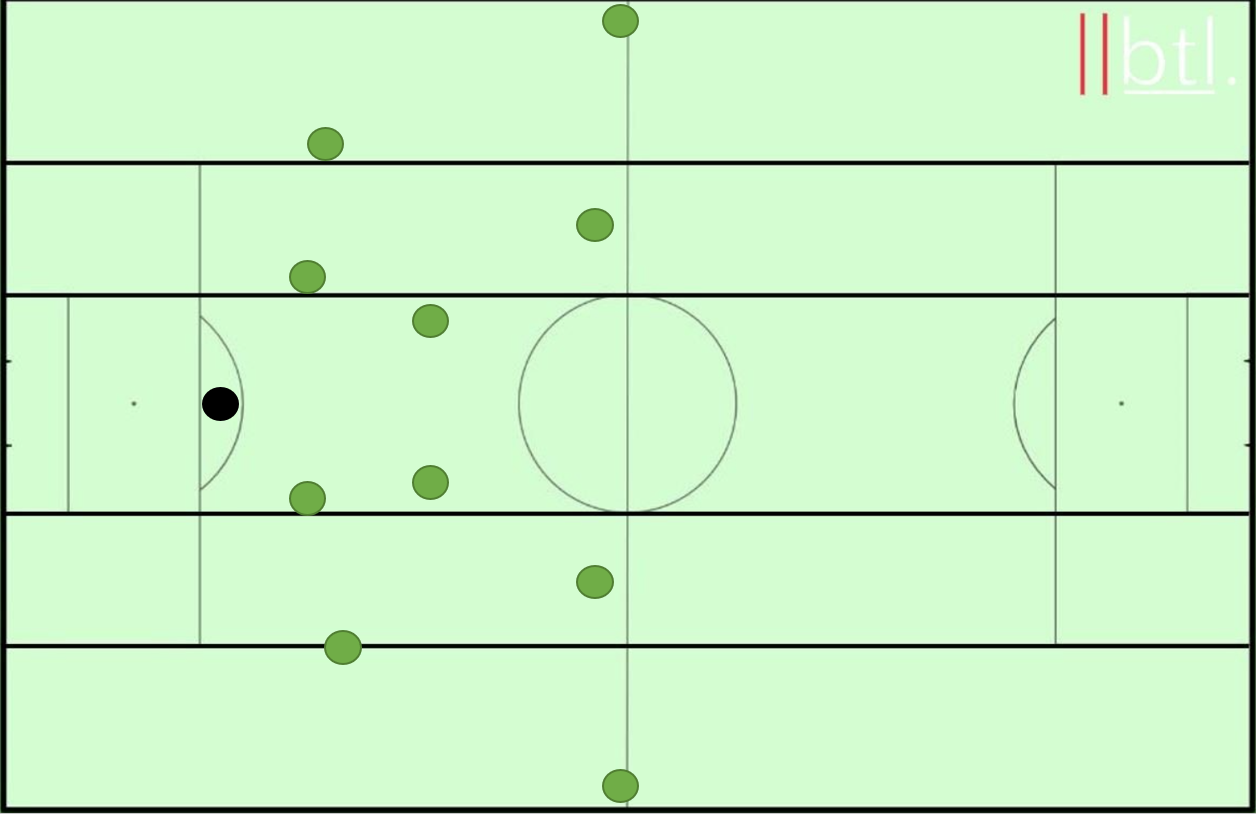

The most important aspect in isolating a player is self-evidently drawing the opposition away from their position. Sassuolo achieve this through prioritising a compact centre during build-up which allows for central circulation of possession, which the opponent subsequently responds to by themselves remaining centrally compact. Meanwhile, Boga and Berardi attempt to maintain (often maximum) width, exploiting the opponent’s requirement to stay centrally compact, generating space for ball reception.

The main method used therefore comes down a coverage/compactness conundrum for the opposition as they are unable to make the pitch artificially smaller horizontally when the ball is central and there are a many passing options for the Sassuolo players meaning they must stay narrower, allowing Boga and Berardi space outside.

This strategy by Sassuolo is the inverse of what is typically seen, as the full backs stay anomalously narrow during build-up. This build-up method creates a degree of distance between the wingers and their respective full backs before engagement.

The 4-2-3-1 shape often morphs into a 4-2-2-2, with the wingers representing the last vertical line when building up as the wingers pin the opposition’s defenders, preventing them from closing the forward and attacking midfielder who are often horizontally staggered in between the first and second lines.

This becomes pertinent as the full back on the outside will make an overlapping run after a defensive midfielder has dropped into create a back three allowing the wide centre back to occupy the deep narrow full back position, permitting the full back to push wider. Because of the half-space positioning of the forward/attacking midfielder, the opposing winger must remain centrally focused in his coverage to prevent the ball from breaking the lines.

This allows for the creation of a 2v1 situation when the full back is progressing. This movement juxtaposes the now inverting winger as they can move inside to more dangerous central areas as the opposition full back is faced with a conundrum of permitting the overlap through coming narrow, making the decision for the winger, generating a crossing opportunity.

Alternatively, the opposing full back can track the overlapping run, deciding to show the winger inside hoping the congestion of central areas will nullify danger, or in deeper areas, it can be used to attempt to stop a transition as the time taken by the winger is often sufficient to slow down the attack directly leading to a lateral or backwards pass allowing the defensive side to regain their structure, albeit deeper, thus allowing Sassuolo to have gained territory.

With the advanced full back, it also grants Sassuolo an opportunity to overload the ball-side half-space in hopes of creating another transition as the far-side forward can drift wider to provide a passing option, unlikely to be tracked by his respective centre back due to fear of exposed space, opening a small gap for a pass to the near-side forward or full back.

Should option 2 of cover the overlap occur, it can allow for another 2v1 situation to be achieved, this time on the opposite flank as the inverting winger can dribble across, opening space for a pass while attracting defenders attention where the same conundrum will be posed to the full back in a more advanced area – track the full back and allow the run, or track the run and allow the pass.

Pertinently, the far-side winger holds width as to receive in these situations as to receive these cross-field balls with time and space. Through this pattern, Sassuolo create a 3-2-5 shape in attack with the ball-side full back pushing forward. In more consolidated phases where the opponent may have constrained the winger or full back to the flank depending on phase, an underlapping run is frequently effective because it drags the central runner.

This causes a similar conundrum to the overlap as to when responsibilities change, with the tracking of the run often leading to vacated space in the centre creating space for circulation to the far-side where numerical/qualitative superiorities can better be established through additional time and space.

The principles of positional play are used throughout this sequence as to create optimal spacing demonstrated most clearly by the horizontal interchanging of the full back and winger, but additionally through aspects such as a dropping defensive midfielder permitting the establishment of better wide connections, the prioritisation of the centre and the finally, the exploitation of the qualitative superiority through the space created.

However, what makes this move so effective is its simplicity because, as the while the antecedent steps which allow for maximum width to be effectively achieved are crucial for consistent application from phases of consolidated possession, moments where a winger can stay wide and full back sit narrower relatively to subsequently rotate occur spontaneously and often. It is not necessary for this move to meet a predetermined script, rather applying broad positional play principles suffices.

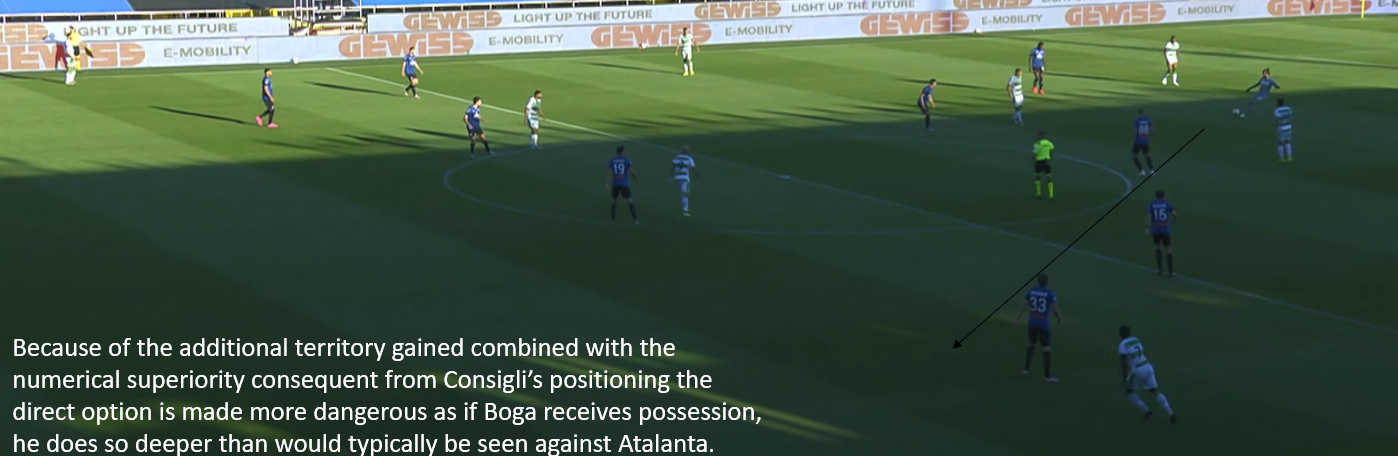

Wingers maintaining maximum width and vertically stretching can also be dangerous directly from direct balls, particularly from an advanced Andrea Consigli which generally occurs against teams which man-orient across the pitch from goalkeeper consolidated possession.

The wingers on the last line are thus granted space run into as they are stretching the back line vertically, while horizontally increasing the gaps in between the lines for passes to be directed in behind creating potentially dangerous deep attacks directly where the wingers are exposed 1v1.

This is beneficial for second ball situations as well as the forward and attacking midfielder are more optimally positioned deeper in the centre to contest, while the opponent lacks compactness due to the vertical and horizontal stretching from the wingers.

This can be seen most clearly against Atalanta because their man-oriented marking style generates space in between the lines as their opposing markers seek to get tight as demonstrated by the example in last seasons fixture, or more recently on the 2nd of May where Boga yet again could get in behind causing a red-card for goalkeeper Pierluigi Gollini.

The movement of Sassuolo’s wingers from this wide position is inwards meaning they are penetrating central areas deep which is more dangerous than the converse of the space to receive being out wide. Although it should be noted this strategy is anomalously effective against a side as rigid in man-orienting as Atalanta.

Other more direct strategies of reaching the wingers in space include the far-side (although still centrally compact) DM coming to receive from the centre back which if facing man-orientation draws the midfielder close out of position, facilitating an up-back and through sequence to the attacking midfielder/forward in the half-space who can then play it out to the winger quickly as they are presumably marked tightly when dropping.

This sequence can also lead to the primary pattern discussed as the wide CB plays it out to the full back who can progress. Additionally, because of the dropping central forward line and pinning wide players, Sassuolo can create a qualitative superiority through quick movement of possession when facing man orientation at goalkeeper consolidated possession such as in this example against Atalanta.

Hamed Junior Traorè drops deep to receive the ball, playing it to Grégoire Defrel, which opens a passing lane to Boga who is now isolated 1v1. The wide positioning grants space to receive because of the necessity to cover potentially dangerous central 1v1’s through darting runs which can occur when two centre backs have committed to and failed at preventing progression.

This links to the importance of them being high as space must be allowed because there is no additional line of support for the defence afterwards, while it moreover vertically stretches the opponent granting them more space to receive in behind should they be tightly marked.

With regards to solutions, I think a ball-sided man-oriented press is most effective; however, the ball sided element as crucial as activation without sufficient compactness generates too much space in between the lines to be effective, creating a weakness to through balls and quick sequences exploiting the space in between the lines as man orientation makes reception with back to goal difficult; however, if there are complementary runners with initiative in addition to space to run back into, transitions can occur quickly.

Through waiting for the ball side, it becomes easier to constrain and limit space available which can eventually transform into ball-oriented pressing. This aims to negate the effectiveness of the one 1v1 through preventing the winger from having too much progressive space through preventing turning, with the potential weakness being the potential for a switch after a backwards pass. The fluidity with which Sassuolo transition between shapes makes this potentially risky, as quick circulation to the flanks could allow the winger the ball before the marker has gotten tight leading to a 1v1 situation as designed, hence, demonstrating the value in having a qualitative superiority in that region.

In summation, Boga and Berardi are two of Sassuolo’s most talented players, as abstract as that term is (Manuel Locatelli being another notable feature), which makes using their abilities a paramount concern of Roberto De Zerbi. Through focusing on centrality and holding maximum effective width through said centrality in addition to the connection formations mentioned throughout this article, the promising Italian manager has managed to get the best out of these two players while still maintaining the positional principles which make the team effective and distinctive. If anything is to be garnered from this article it should be:

When the ball is central, the players occupying wide spaces are often free because of the necessity to remain centrally compact. This makes them easier to isolate should mechanisms of transition be in place to facilitate smooth progression which means the ball reaches the winger before the opponent has shuttled to compact the space. Should that happen, the mechanisms in place should ideally have a juxtaposing under/overlapping run to drag crucial markers away to generate space for switches for better 2v1/qualitative superiority positions to occur closer to goal.

Additionally, having the horizontal stretching players as the vertically stretching players can be useful as it simultaneously makes tracking runs tightly difficult increasing the attractiveness of the direct option into space as gaining better wide coverage sacrifices compactness as to make the through ball easier and allow for more dangerous central 1v1’s with potential link-ups down the flanks as the covering player is often the one responsible for the wide outlet.

In general, it moreover makes them more likely to receive due to the additional space, which provided there are connections such as a half-space player in between the lines and overlapping full back dragging the potential pressing player, makes progressing up the pitch an easier process. If the principles were codified, it would look something approximating this:

- Hold width through wingers.

- Have a central basis with potential connection establishment mechanisms.

- Winger and fullback always occupy different zones.

- Juxtaposing movement from ball side full back.

- Central recycling option.

- Player inside the ball-side half-space to make a space creating run/make a passing option.

- Deeper far side full back in similar dynamics to when possession is central.

By: @mezzala8

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / Marco Luzzani / Getty Images