How Sassuolo Adapted to Crisis and Defeated Napoli

Roberto De Zerbi’s Sassuolo faced off against Napoli at the Stadio San Paolo with several key players including talisman Francesco “Ciccio” Caputo, Domenico Berardi, and Filip Đuričić missing. In response to this, De Zerbi changed to a fluid system that allowed them to interchange between a 3-4-3 in possession and a 4-5-1 mid block off the ball.

De Zerbi opted for this system in order for Sassuolo’s back three to maintain numerical superiority against Napoli’s strike pairing of Dries Mertens and Victor Osimhen. As a result of this, Sassuolo’s wide center backs could stretch apart the two strikers and allow one center back with the time and space to explore passing options in possession (Vlad Chiricheș in this example).

Despite trading their traditional 4-2-3-1 formation for a 3-4-3, Sassuolo continued to adhere to their strategy of positional play by achieving numerical superiority, allowing them to penetrate in between Napoli’s lines of defence. The centre backs constantly had a numerical and positional superiority against the front two because of the wide spacing.

Positional superiority was achieved in the wider corridors as Napoli’s flanking midfielders could not simultaneously cut the passing lane to the inside forward whilst still covering the wing back. If one of the wider centre backs went unpressed, he could then gain territory and play a penetrative pass, meaning one Napoli player had to close him down which opened up another passing lane.

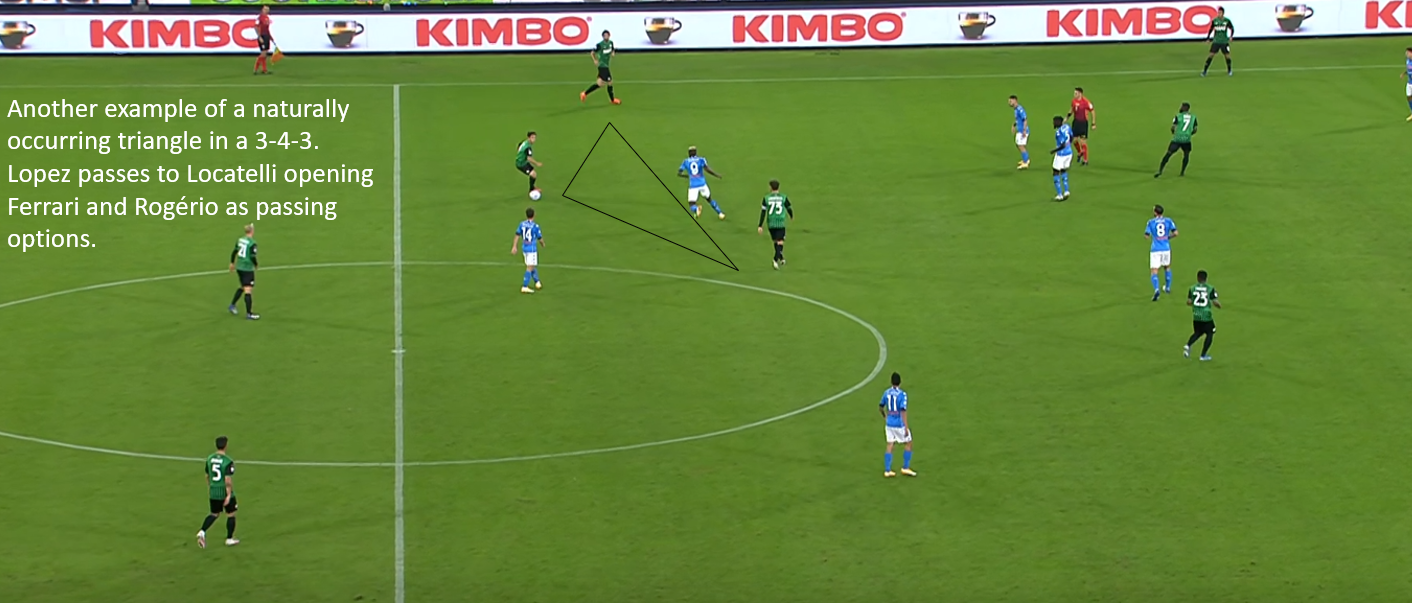

We can see this in the below example, where Sassuolo’s double pivot of Maxime Lopez and Manuel Locatelli occupies space between the lines, which means that if Mertens chooses to press the defender on the ball (as he does with Gian Marco Ferrari), this opens up another passing lane for Ferrari to play into.

If pressed, the numerical superiority becomes important because the back three allows for a constant deep central option to be available against a shuttling mid-block which attempts to engage on the second line. As a result, Sassuolo run fewer risks in possession as there is always the safety net of the lateral pass to switch the ball and attempt to combine again.

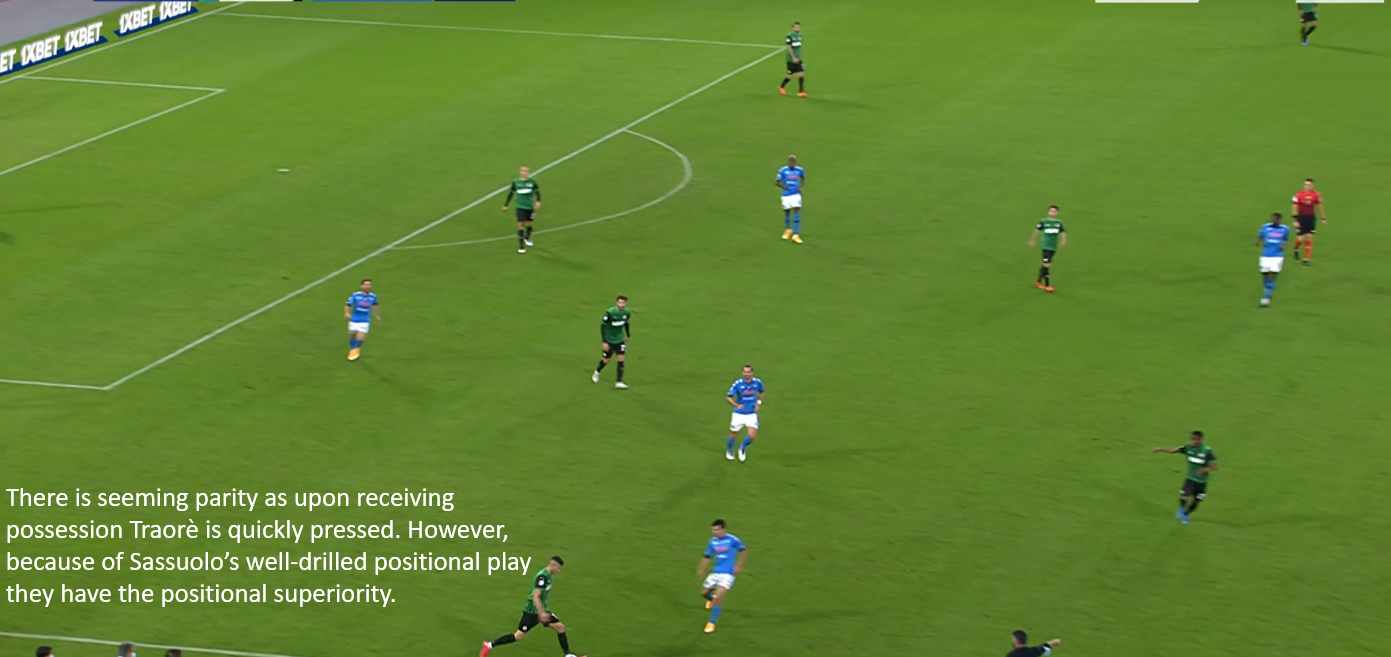

The effectiveness of Sassuolo’s positional play is demonstrated in the image above, as Mert Müldür plays the ball into Hamed Junior Traorè’s feet who upon receiving is pressured by Elseid Hysaj. This lures the Ivorian midfielder into a compression trap, but because of the intelligent positioning facilitated by positional play, a passing lane back to Müldür remains open.

As a direct result of Fabián Ruiz committing to the compression trap on Traoré, a passing lane opens up towards Locatelli. Sassuolo exploited Napoli’s tendency to change their focus based on the positioning of the ball, which is a natural response, but this resulted in Sassuolo continually having open passing lanes.

Sassuolo consequently created space through quick passing combinations rather than movement as they lured Napoli into pressing whilst still maintaining their positions, which continued to create increasingly advantageous passing lanes.

This is an example of a naturally occurring triangle facilitated by Sassuolo’s principles, which potentially explains why De Zerbi felt comfortable changing to a 3-4-3, a system he used earlier at Sassuolo during the 2018-19 season.

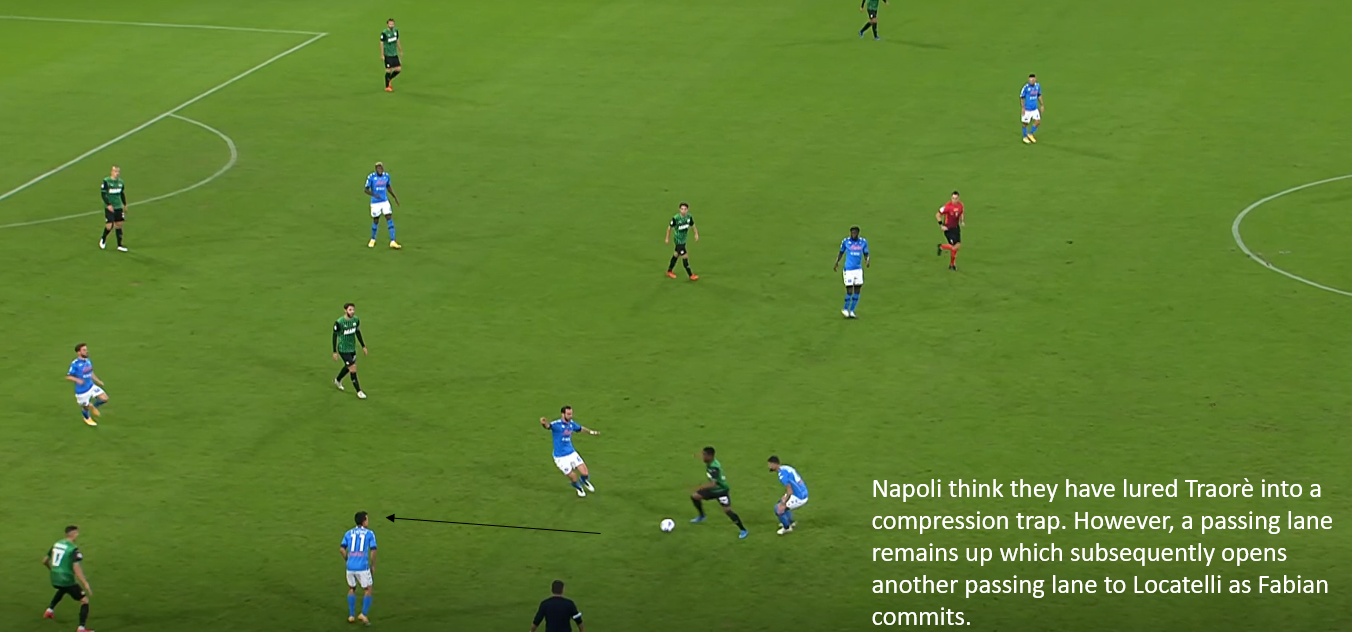

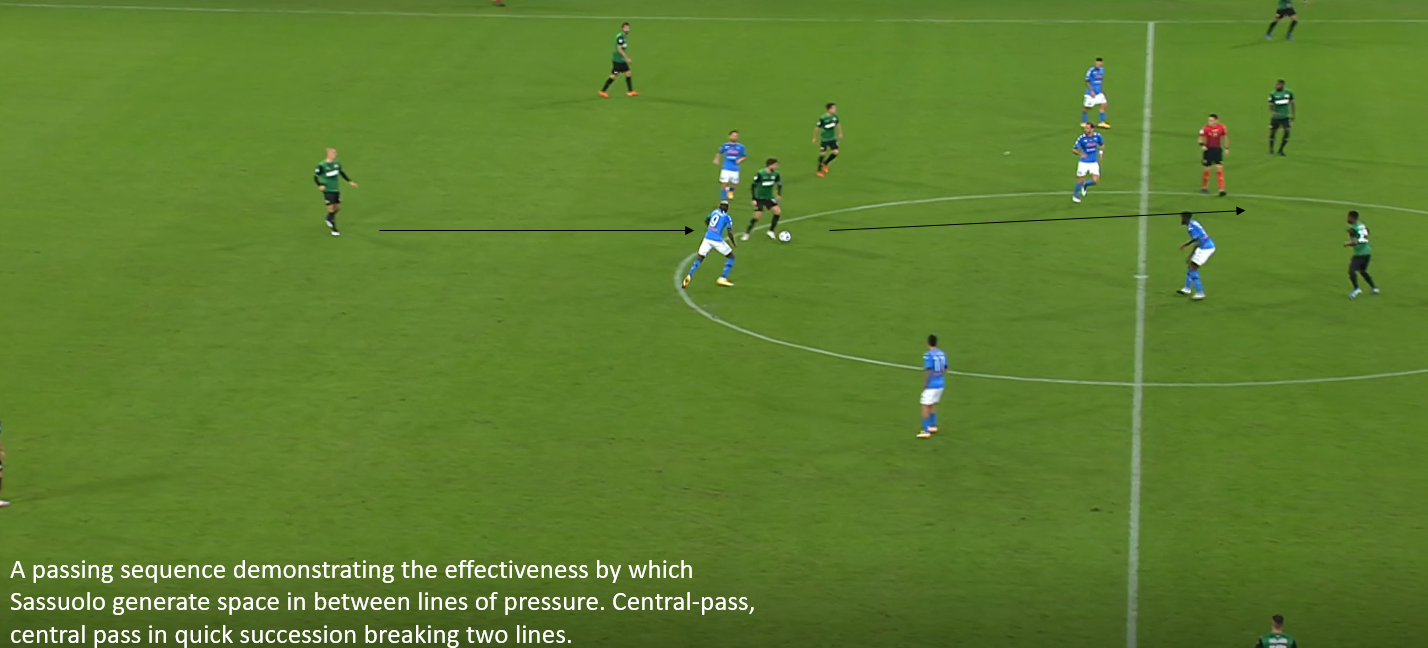

The subsequent move by Locatelli moreover displays an idealised form of positional play as he moved the ball centrally to Lopez. who played it back to Chiricheș. who played the ball to the opposite flank. Notice how Lopez scans knowing he will receive possession; he is aware that the action of Locatelli receiving the ball implies he will receive. Not once did a Sassuolo player exert any strain when moving, everything was created by the system and the opponent.

This is generally successful because of the logic that the ball moves faster than players, and thus, if the structure facilitates quick passing, the opponents shuttling to compress space is nullified and their lack of coverage is exposed.

In this example, Lopez hit a slow pass to Chiricheș which meant a reformation with gained territory rather than fully exploiting the created space, but this sequence nonetheless displays the remarkable coaching of De Zerbi, as every action had a purpose – create space through moving the opponent – this was achieved from the wide triangles that were created in a 3-4-3 which allows for a press to be baited safely and then moved to the middle of the pitch again.

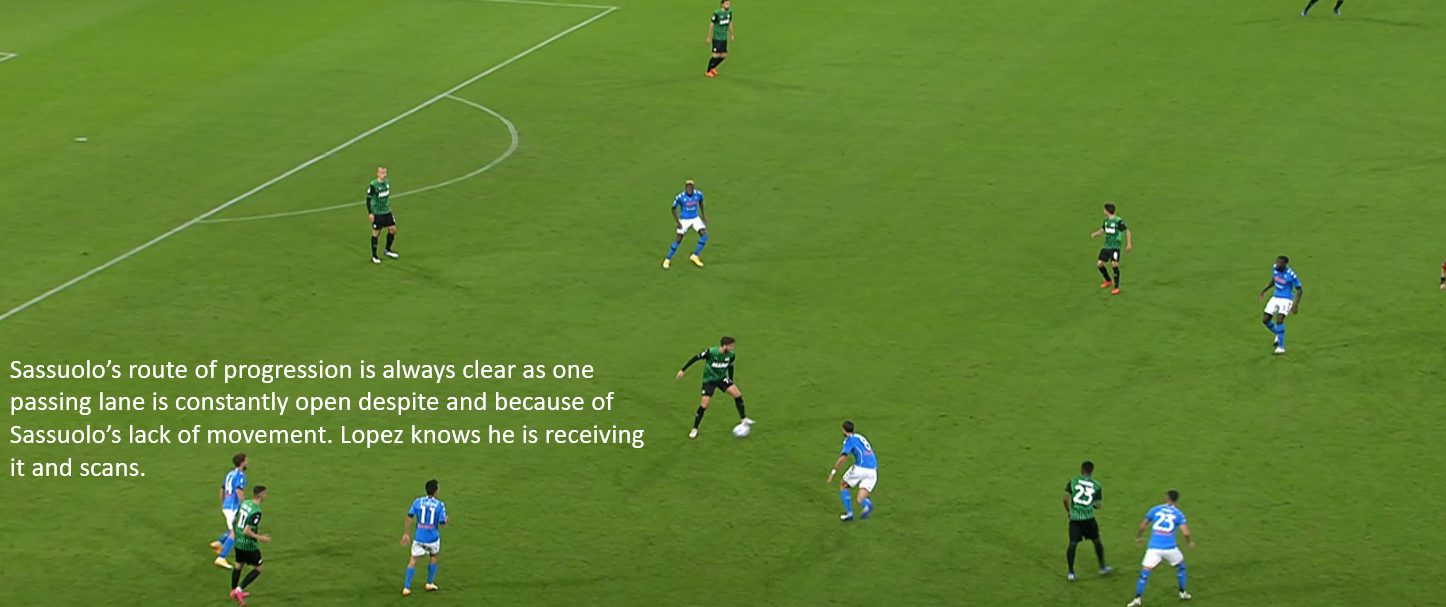

These types of positional/numerical superiorities occurred consistently as Sassuolo’s coverage of the pitch meant that short passing triangles were always available which allowed for switches to occur when the ball moved centrally. It was impossible for Napoli to remain compact while covering all available passing options which often meant they had to continually cede territory.

This came as Sassuolo stayed gradually progressive through short wide interchanges into switches through the conduit of central players until Sassuolo were deep enough to whereby they lost the numerical superiorities and had to take risks to create chances. Thus, when possession had been consolidated, Sassuolo were almost unstoppable until they reached the final third.

The below example elucidates a variation from how they typically play, as progression was achieved throughout horizontal superiorities with the back three as opposed to vertical passes. The progressing back three would slowly gain territory as possession was circulated between the deeper seven players, what their skeptics may call ‘lateral passing without intent.’ As demonstrated, though, the logic was sound and it created plenty of dangerous opportunities while still maintaining control.

Control was the crucial element on the day, as they starved Sassuolo of the opportunity to create through possession by keeping players deep and allowing them to remain conservative and risk-averse against the counter.

This creates the question of whether or not possession for possession’s sake is even a thing when the game state is favourable as it serves a defensive purpose. The game state being favourable tends to vary depending on the ambition of the club, but in this instance, it ensures that they could maintain possession.

Quite simply, if the opponent do not have the ball, they cannot score, and if they did get the ball despite largely safe passing until the final third bodies will be back to provide defensive cover. Control was the priority with this approach, as Sassuolo wanted to dictate how the game transpired, which in the first half particularly was one of very few chances.

This style of defensive football suits their playing style to a much greater extent as it has more continuity with how they seek to play and covered for their weakness of depending in a deep block. Furthermore, it is more responsive to the opponent without tactical changes as it still desires to capatilise upon space, just the context for which that space is deemed exploitable is changed as fewer risks are taken.

To summarise, playing with deeper players in possession allows for the simplest numerical superiority to occur more often, which forces the opponent to accept a passive game state or press, thus exposing more space in between the lines due to the positioning of the inside forwards and the width held by the high full backs.

This allows them to transition from a numerical superiority to a positional superiority in between the lines which forces the opponent to either retreat or disorganizes them through aggressive defensive pressing.

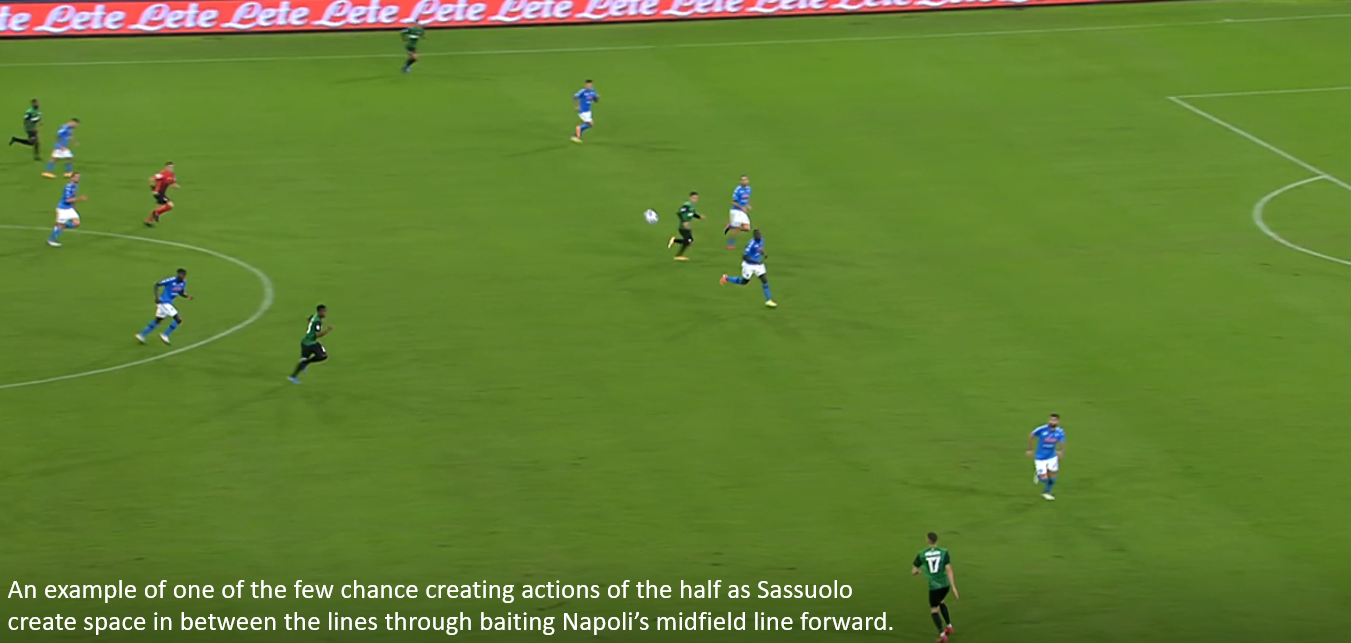

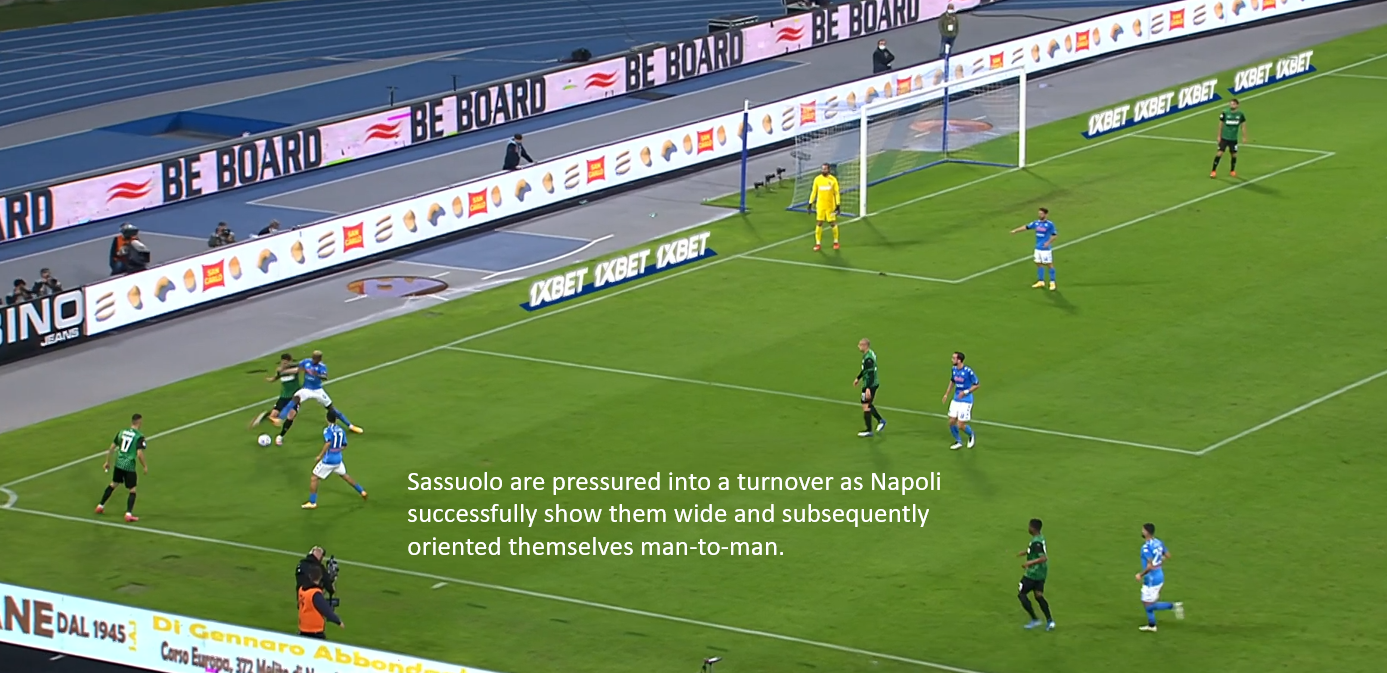

Napoli attempted to adapt to this situation through applying ball-side pressure in more advanced areas to unsettle Sassuolo’s attempts to consolidate and build. However, this provided Sassuolo with a clear route of progression in between the lines and caused issues of detachment between midfield and defence. This reaction was understandable as Napoli needed to grapple back control of the game and keep Sassuolo’s back three in a deep position, and on occasion could generate a turnover.

Despite the formation change, Locatelli’s proclivity to drift centrally remained as he sought to take advantage of the pitch in order to stretch play. The fact that he continually found space in between the lines without being pressured is a testament to how effectively Sassuolo generates space in between lines of pressure.

This is only possible when spacing is well regimented so as to stretch the opposition to maximum capacity – the next step is quick ball circulation in order to move the opponent which is then facilitated by the shape and enables them to quickly break two lines quickly through central progression against a side known for defensive solidity, showing just how effectively they can manipulate the opposition.

When analysing the match, it can be difficult to ascertain why certain things happen as they do, such as the lack of intensity in Osimhen’s pressing which consistently allowed Sassuolo possession in between the first line, although Gennaro Gattuso may have thought energy conservation was more important against a team which manipulates their positioning like Sassuolo do.

Nevertheless, the Nigerian forward often found himself behind the game and reacted too slowly to the actions unfolding. However, it should be mentioned that when setting the pace through pressing rather than shuttling, he looked far livelier on the ball.

The desire for Locatelli to move centrally was the primary reason behind why they were more oriented around the left-sided build-up, as Lopez would move to support wide link-up, thus allowing Locatelli to be vacant in the middle. Ferrari often moved to the left back position which stretched Mertens and created a 2v3 superiority in the form of a triangle down the left flank. The alternate option was a free pass inside to Chiricheș into Locatelli as detailed above.

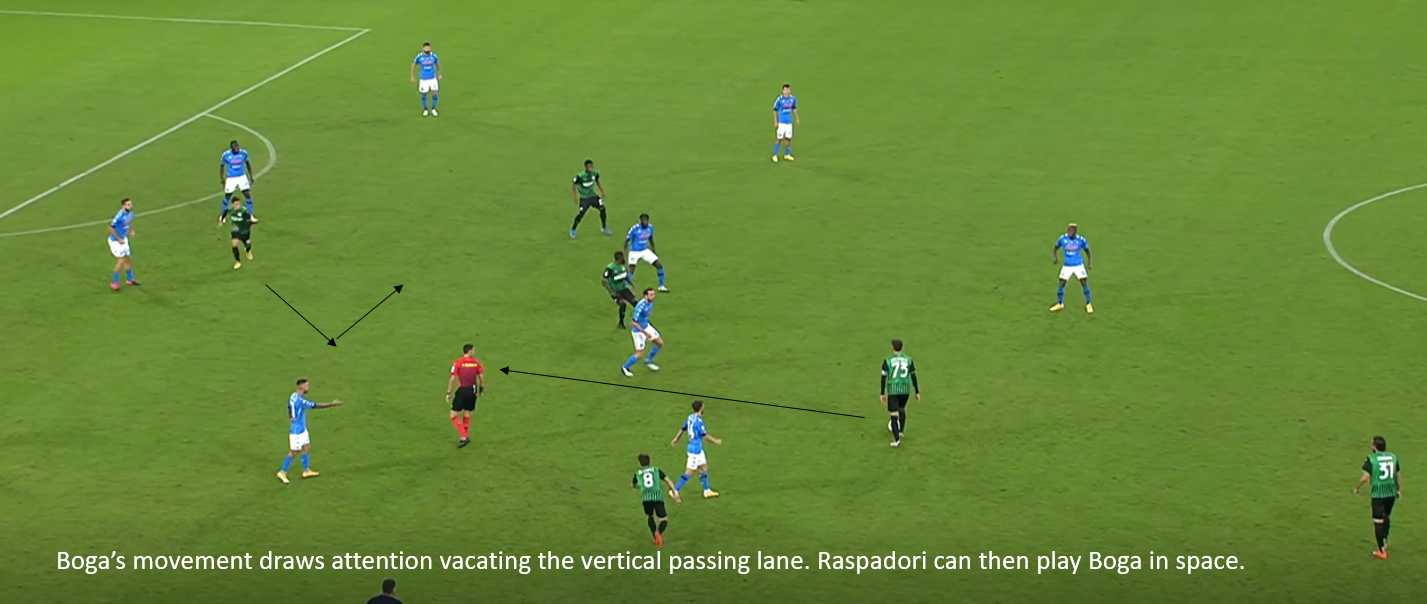

An example of Sassuolo’s positional play yielding proximate rewards can be seen in how space and passing lanes are generated in between the lines antecedent to the penalty being won. Jérémie Boga and Locatelli occupy the same vertical zone so as to create a progressive and regressive passing triangle for Lopez. Logically, Napoli cover the man in possession and the progressive option, resulting in Locatelli receiving possession.

Upon the ball leaving Lopez’s feet, Boga moves subtly into a more central area. This draws Fabián’s attention, who covers with his shadow while lightly pressing Locatelli, showing that the action of passing to Locatelli implies the subsequent action of Boga to drift and open a new passing lane.

Boga’s movement occurs as Lopez’s decision is being made, meaning he vacates his present position as soon as it loses utility to create a better game-state subsequently. His intention was never to receive possession on that action but draw the opponent out in order to create space.

This results in Giacomo Raspadori drifting into the now vacant vertical corridor, in essence rotating zones with Boga. Raspadori can quickly lay the ball into Boga in space as only the vertical passing lane was covered. Moreover, Raspadori receiving possession draws Kostas Manolas in, thereby creating space for Boga to dribble into which creates the chaos and leads a foul on Raspadori.

Thus, these concepts when applied have practical benefits in how passing lanes are created and therefore how play progresses. The coherency by which these are practiced shows the adaptability of De Zerbi’s positional play in the final third as players think of themselves in relation to potential actions and as actors which can manipulate the opposition to create better circumstances consequently.

There is an element of rigidity in how they position themselves as understanding of zones allows them to position themselves in accordance to other players in order to maximise passing options available, although this is also adaptable as there is no rigidity specifically in how to occupy these zones, or in what manner/order for progressive passes to enter.

The approach is not that different when compared to their typical 4-2-3-1 as rather than a narrow full-back or double pivot member dropping in to create a three, which would enable Locatelli to move centrally to act as the nucleus and a full back to push up, a centre back, often Ferrari would occupy the role. Thus, the overarching concepts and aims take precedence over pre-match shapes, particularly when possession could be held safely, allowing for adaptations.

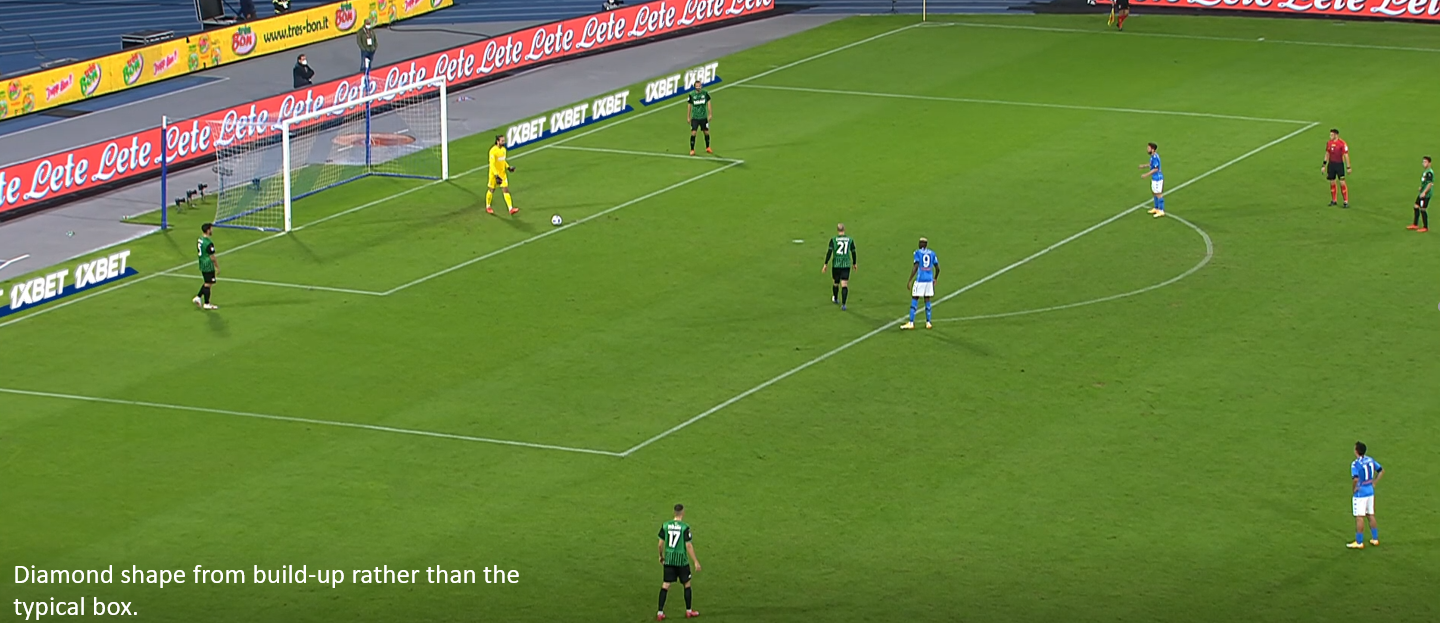

This is not to discount the importance of formations as for instance, rather than their typical box set-up from goal kicks, they created a diamond with Chiricheș at the tip. Moreover, the positioning of the 3rd centre back made goalkeeper Andrea Consigli’s action of pushing higher up to split the centre backs less relevant as that space was consistently occupied, meaning he was far less involved than usual. However, the continuities in style far outweighed the discontinuities.

Another type of superiority accentuated by the 3-4-3 saw Boga permitted more freedom due to width from Rogério at left wing-back, with the aforementioned Ferrari acting as an auxiliary narrow full back when required.

This contrasts to the 4-2-3-1 where the left back is sometimes required to come narrower to support ball circulation, meaning the responsibility to stretch play falls onto the left-winger. This freedom to create and roam is emblematic of a more risk-averse style from De Zerbi whereby more faith was placed upon individuals to link and attack in order to keep more men back defensively.

We can see how similarities emerge between the 4-2-3-1 and the 3-4-3 as the intent remains the same – Sassuolo desire a player in the centre of the pitch deep and central to act as a constant outlet for reception and thus stretching the pitch. The player charged with the responsibility at the base was the only thing that changed rather than the intent.

Thus, in possession Sassuolo were significantly more risk-averse than they typically are, particularly in consolidated regions higher up the pitch as Napoli’s high pressing from goal kicks made short progression risky irrespective of they approached it. The centrally compact 3-2 made it difficult for Napoli to achieve a turnover because covering all passing options was far too tall of a task.

Sassuolo controlled proceedings and negated Napoli’s attacking threat through defensive possession, remaining content in a passive game-state which forced Napoli to press generating space in between the lines. Their play almost perfectly reflected the positional play ideal of moving the opposition, the foremost concern to create space, allowing them to ascertain control and create chances.

The rationale behind the 4-5-1 out of possession for Sassuolo was likely the desire to match Napoli in midfield (4-2-3-1) man-to-man in order to prevent short central progression through making it difficult for midfielders to receive the ball to feet.

Sassuolo’s midfield was oriented in zonal-man fashion rather than simply man-oriented as the midfielders refused to drift too deep in order to follow their counterparts as that would expose space, revealing a zonal element in how they sought to defend which thus prevented positional manipulation.

Zonal-man orientations are typically more responsive to the positioning of the ball, with zonal priorities to close space being more important for the players on the far side, as their corresponding player is not a figure who can receive possession quickly with the contrary being true of the ball side where tighter marking is more likely to be seen.

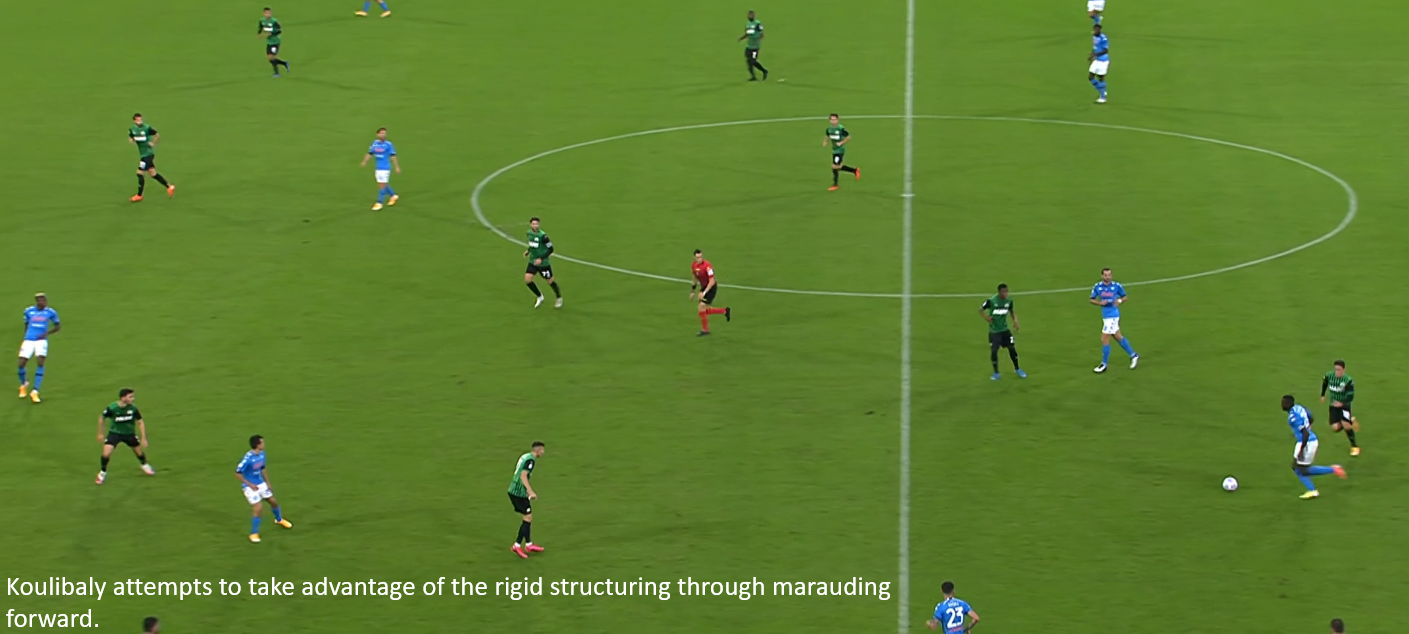

This allowed Napoli’s centre back partnership of Manolas and Kalidou Koulibaly to safely have possession because a zonal/man oriented mid-block places greater emphasis on second line engagements where they seek to make the progression options for the centre backs difficult as they have limited progressive options.

The free players are the goalkeeper – backwards, and the other centre back – lateral meaning risks must be taken to disorganise the defensive block. Such as a marauding run from centre back, something of a speciality for Koulibaly, which are difficult to counter as any pressing would open up a passing option against a now weakened defensive structure.

The movement through phases moreover makes him difficult to track from striker Raspadori as Koulibaly had the initiative in engaging in the run, meaning Raspadori is reacting to events unfolding rather than being in control.

The obvious drawback however is the risk incurred from potential turnovers as a centre back is out of position. However, with a covering player these become extremely effective as the unorthodox movement dismantles defensive structure as the quick movement through phases means he is no one’s responsibility.

Another adaption from Napoli in response to the zonal-man approach of Sassuolo was Fabián dropping deeper and into more central areas to become free. This allowed him time and space in possession as Traorè was no longer responsibility for pressing him due to him leaving his allocated zone.

Despite giving him space, which could allow him to pick a pass, the undesirable spacing resulting from it made progressing difficult. Traorè is relevant for this particular example, although Fabián and Tiémoué Bakayoko rotated frequently thus either Lopez or Traorè would be responsible for each dependent on which zone they occupied.

If Napoli held possession with the centre backs for long duration, one of the midfielders, dependent on the ball-side would press the Napoli centre back in possession to force a decision which would result in Locatelli moving to cover creating a 4-4-2 pressing shape.

This sought to catch Napoli complacent in possession, and with a structure adapted to facing a zonal man 1-2 midfield as passing options were quickly cut. Sassuolo thus created a pressing trap through inviting the back 2 forward and the full backs to advance.

The forward would cut the passing lane to the free full back while having the diagonal midfielder and centre back in his pressing shadow while the corresponding midfielder would pressure the centre back and the other midfielder followed his counterpart in addition to Locatelli covering the space positionally by no longer sitting in between the lines.

This match signified Sassuolo’s first major challenge this season, and was one that they met ably with the Neroverdi ultimately winning 2-0. There is still a significant amount of the season left and dreams of Champions League football are perhaps far fetched, however, the adaptability displayed staking into consideration the lost personnel will definitely act as substantiating evidence for those who consider them capable.

By: @mezzala8

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / Francesco Pecoraro / Getty Images