Tactical Analysis: Barnsley’s Pressing vs. Chelsea

This article will attempt to provide a holistic analysis on the way Barnsley pressed Chelsea in the FA Cup in January, whilst also focusing on how Chelsea combated this by altering their build-up structure.

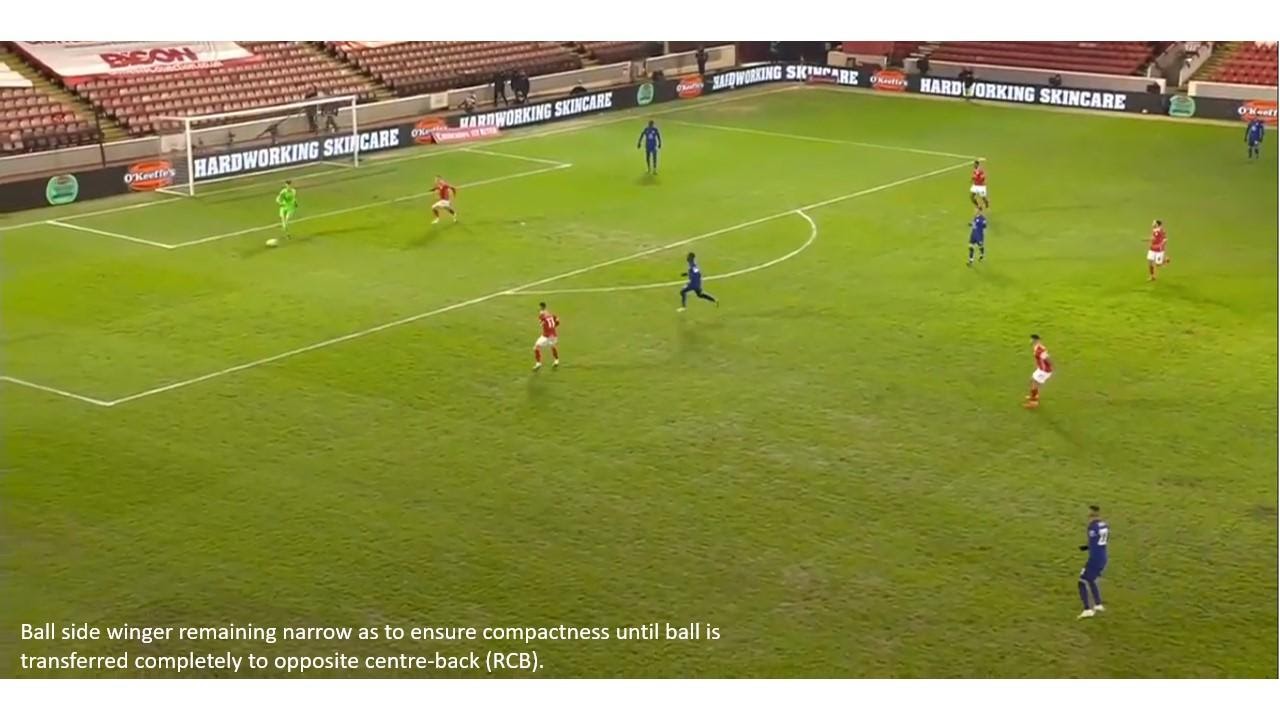

During the opening 15 minutes, Barnsley pressed aggressively with a high level of engagement. They pressed in a 5-2-3 which contained a mix between zonal and man-oriented pressing. There seemed to emphasis on remaining centrally compact, hence the tight configuration of the front five when the ball was central.

Barnsley seemed to force stagnant, deep possession as a consequence of their centrally compact shape, thus the primary trigger to press the ball seemed to be consecutive sideways passing across Chelsea’s back three, more prominently when the ball was moved laterally from one flank to another (RCB -> CCB -> LCB).

Therefore, including context, the press manifested itself in the following steps: 1) as the ball was being moved laterally from one side to the other, the ball side winger would remain narrow and prevent vertical passes into midfield until the ball was played from the goalkeeper or central centre-back to the wide centre-back. This would be the trigger for an intense, wide press.

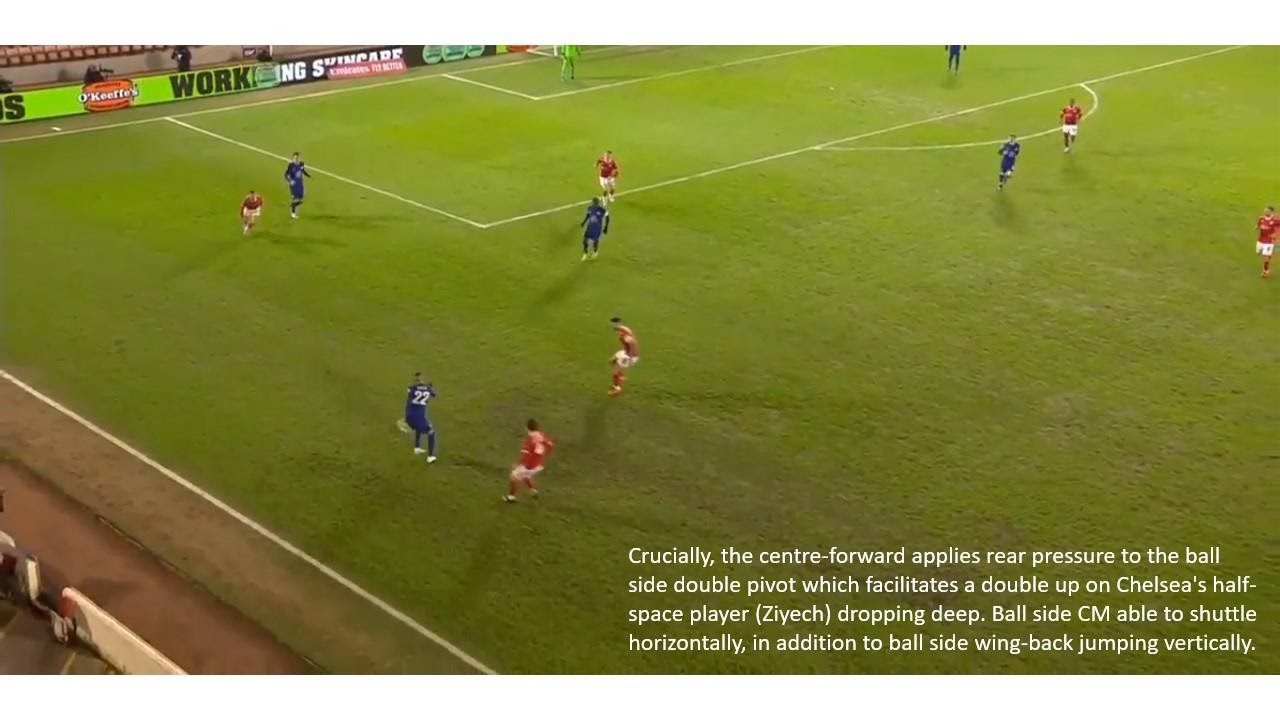

2) As the ball was received by the wide-centre back, Barnsley’s centre-forward, Cauley Woodrow for large parts, tracked the ball side pivot instead of preventing a lateral pass to the goalkeeper or across the box. This proved to be a crucial factor, because firstly it prevented Chelsea’s double pivot from simple reception, and secondly, perhaps more pertinently, it facilitated step 3, which was the source of multiple turnovers in the opening 15 minutes.

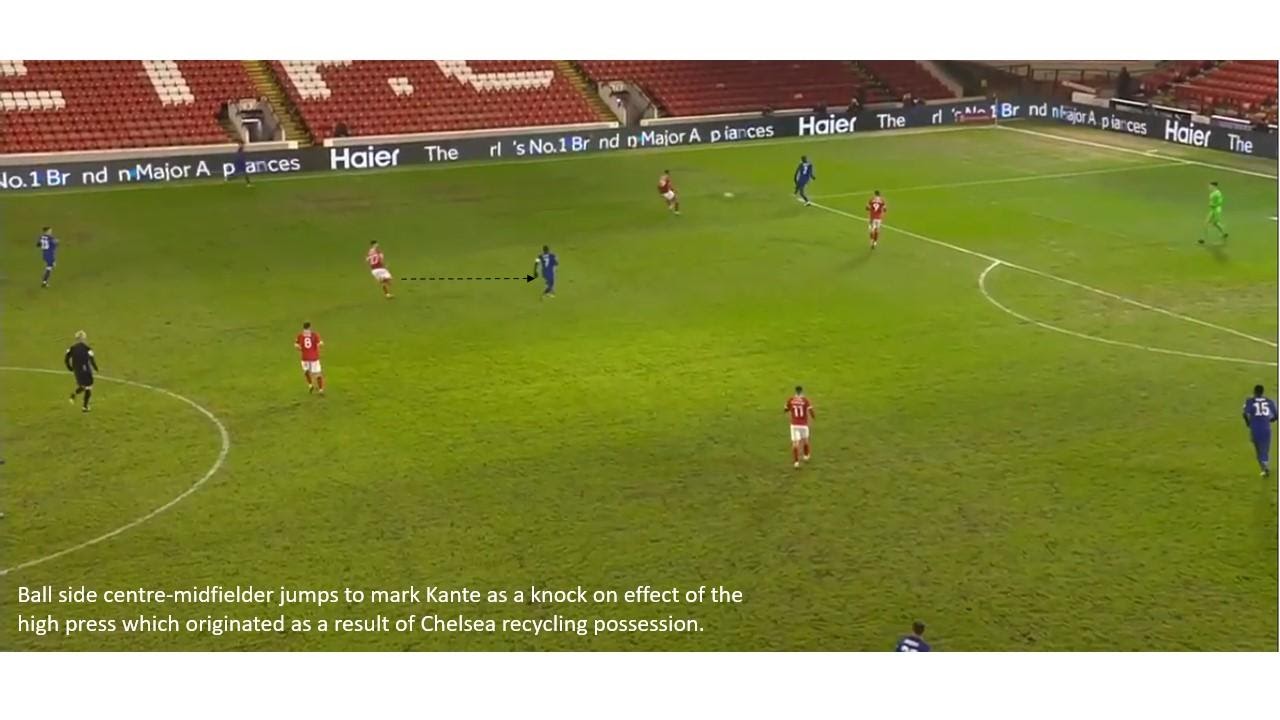

It essentially allowed the ball side central-midfielder to jump wide to pressure the receiver from the wide centre-back’s pass, rather than jumping vertically to pressure the near side central-midfielder (N’Golo Kanté in this case). Consequently, Barnsley were able to create 2v1 overloads as a result of the rear pressure applied by the recovering centre-forward. The 2v1 facilitated more aggressive pressure The 2v1 facilitated more aggressive pressure and thus a greater volume of turnovers than anywhere else on the pitch.

An anomalous aspect of Chelsea’s build-up was that the inside forwards (players who occupy the half-spaces in the 3-4-2-1) often dropped deep to support build-up play when the wide centre-back on their flank received possession, rather than the wing-backs dropping deeper on the touchline. Rather, the wing-backs remained very high, stretching the pitch horizontally and vertically.

My personal hypothesis is that they attempted to lure the wide centre-backs forward which in turn would create space further up, specifically for the wing-backs to isolate Barnsley’s wing-backs 1v1. However this was largely unsuccessful because the inside forwards often received with their back to goal. Backwards reception is quite a common trigger for a more intense press, especially in deep areas.

Also, the distance that Barnsley’s wing-backs had to cover in order to engage the inside forward when dropping deep was shorter than if the wing-back was dropping down the touchline, which in turn reduced the amount of time and space they had upon reception. This was perhaps exacerbated by the seemingly bumpy pitch surface which often impacted first touches.

Barnsley’s solution was to allow the wing-back to advance to press the inside forward, whilst the remaining defenders would shuttle across to cover the ball side, including the ball side centre-back pushing extremely wide to engage the wing-back on the touchline.

This contained an element of risk, given that it required a significant shuttle to adequately cover the ball side, which made it difficult to maintain short distances between the centre-backs, which was exacerbated when Chelsea moved the ball quickly in deep areas because the location of possession was consistently changing and thus was the Barnsley shape.

The space between the lines created via Chelsea’s deep double pivot and Barnsley’s aggressive approach early on was not pertinent due to the central compactness of the 2-3 pressing structure. This essentially meant that direct balls were the only feasible way of progressing the ball to the front five, which was supplemented by the concept that defenders, especially wide centre-backs, have greater freedom in a back compared to a back four to step out and apply pressure onto opposing attackers between the lines.

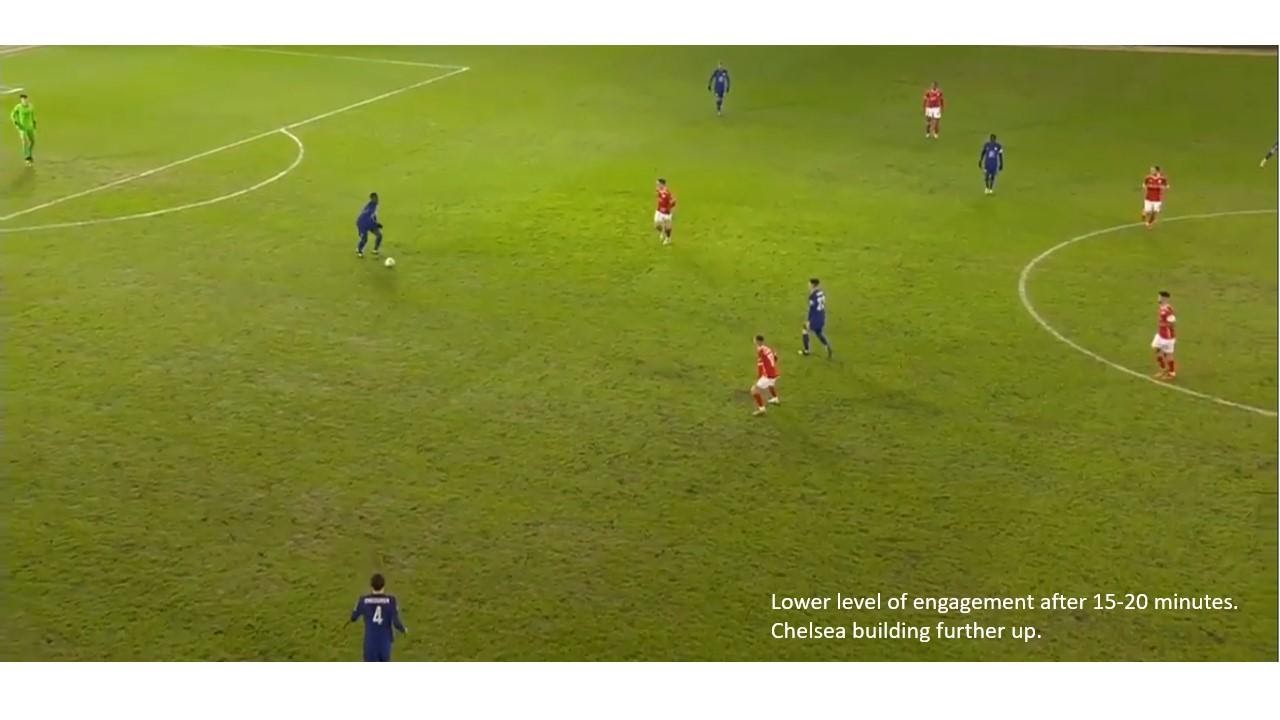

At around the 15-minute mark, Chelsea gained territory and began to build slightly further up, with Barnsley seemingly content to sit off and engage in deeper areas, rather than further forward. This perhaps followed the old cliché “press them first 10 minutes to let them know they’re in a game”, before retreating afterwards. It was an understandable decision considering the quality of opposition, however, due to its success, and the lack of solution from Chelsea’s perspective, it was a surprise to see the high press abandoned so quickly.

The principles that were evident in the high press essentially remained similar, with the only difference being that Chelsea’s half-space players were less likely to enter wide zones in consolidated possession due to the wide coverage already being obtained via the wing-back and also the wide centre-back. Consequently, the Barnsley double pivot was more centrally oriented, focusing primarily on N’Golo Kanté and Billy Gilmour, rather than pressing wide areas.

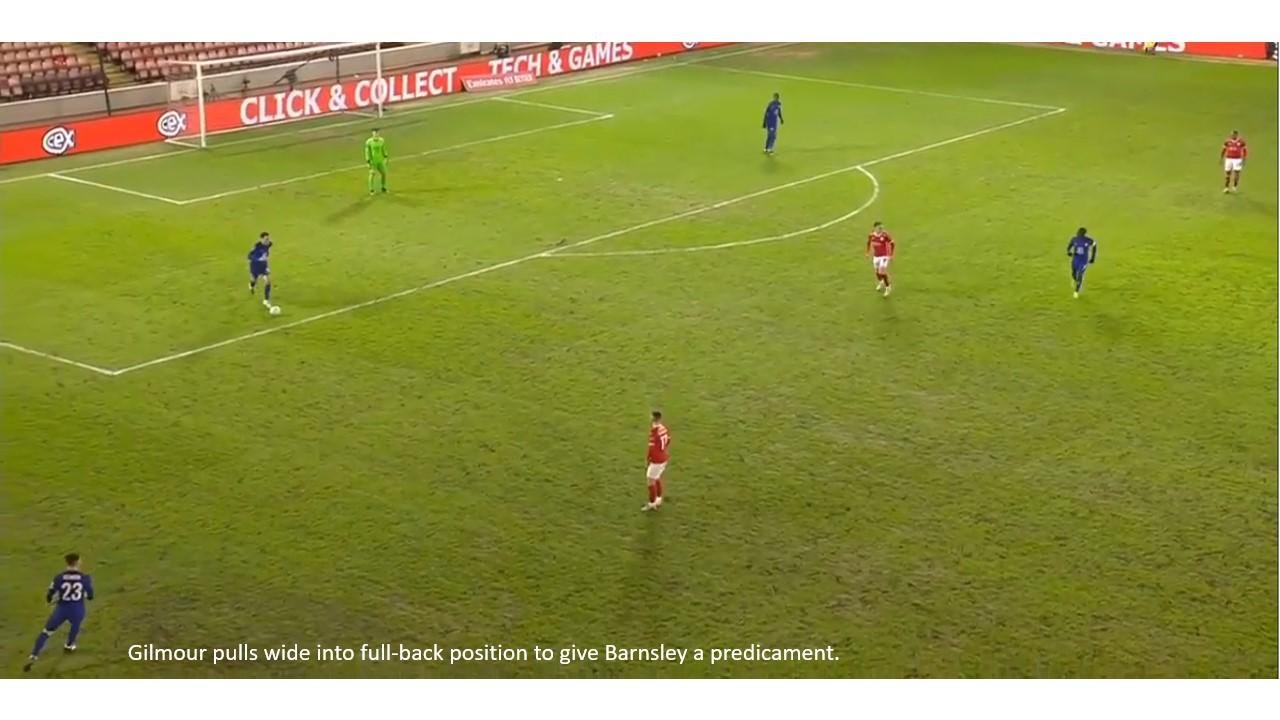

This was when Chelsea enjoyed arguably their best spell of the match, and it was primarily down to the in-game adaptation of dropping a centre-midfielder into a deep full-back position or into the centre-back position, granting freedom for the wide centre-back to move into a full-back position.

This was advantageous for Chelsea because it essentially prevented the ball side winger from pressing the right centre-back when they had deep possession because it would increase the distance between themselves and the newly formed right-back , which in turn would create space for them and therefore they would be a more lucrative passing option.

It was perhaps too risky for the ball side wing-back to jump forward and press the full-back in order to combat this, predominantly due to the need for them to initially remain deep to prevent a direct pass into Chelsea’s wing-back, and therefore the press could only be initiated once the ball was played, which is too late to cover the adequate distance required in order to apply pressure and prevent progression.

Additionally to the wing-back, it was also perhaps too risky for the ball side central midfielder to jump wide (like their responsibility during the opening stages of the match) due to the loss of central compactness. This would have opened significant central space and therefore would have allowed Chelsea to progress through central areas (the double pivot) and therefore switch to the underloaded flank quickly, a dangerous prospect given Barnsley’s commitment to the ball side.

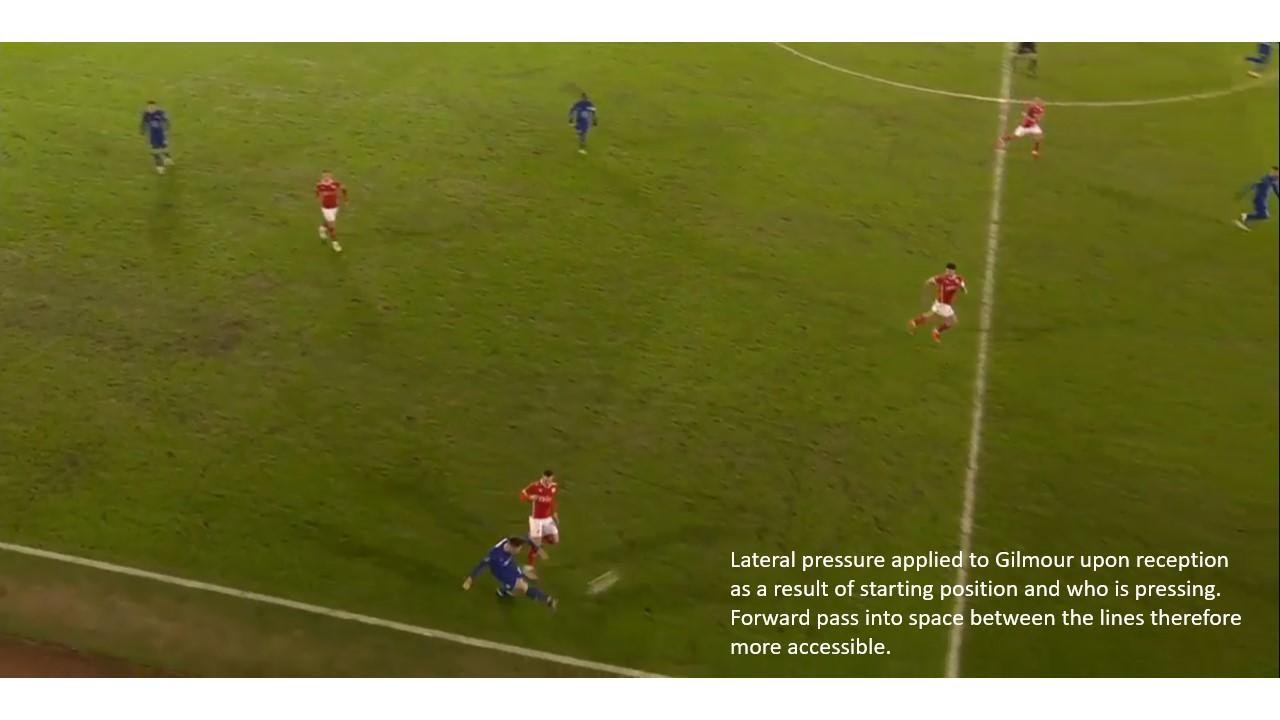

As a result of these factors, the ball side winger would maintain a position whereby he could prevent a vertical pass into the half-space, but also access Gilmour via a short shuttle once the pass had been released from the right centre-back. When the pass was played, the winger would jump out and apply aggressive pressure, however, the pressure applied was lateral due to the starting position of Gilmour (slightly more advanced horizontally than the winger) rather than vertical, as it was when pressing high from the front.

This essentially means that forward passes are still available in the time the winger is covering the ground from remaining compact to pressing the ball. Vertical pressure can prevent forward passes without being close to the ball due to cover shadow pressing, however, lateral pressure is likely to block inside passes to a certain extent. This meant that the space between the lines was now more pertinent, simply because it was more accessible due to the lateral pressure being applied rather than vertical pressure.

With the space between the lines being more accessible and therefore more dangerous from a defensive perspective, there was more pressure on the centre-backs stepping out and preventing simple reception between the lines. However, on this occasion, they were slow to react, therefore allowing a forward pass into the space behind the defence, as Callum Hudson-Odoi, Chelsea’s wing-back, carried forward momentum against Barnsley’s wing-back and delivered into the box.

After a period of sustained Chelsea possession, Barnsley showed that their high press, specifically the press on the half-space players dropping deep (particularly Hakim Ziyech who seemed susceptible to pressure on the pitch surface), was still effective in the 41st minute. One route of exploitation that Chelsea should have perhaps explored to negate the press was to play one-touch passes from the dropping half-space player into the ball side pivot.

The quick release would have firstly, dragged Barnsley’s ball side wing-back and central midfielder forward and wide respectively, thereby causing Barnsley’s defensive line to shuttle across, and secondly, it would have allowed the ball side pivot to escape the rear pressure of the back tracking centre forward as he would not have been able to cover the adequate distance in time.

This would have facilitated a switch to the opposite flank via the ball side pivot, where left-wing back Marcos Alonso was in space due to the lateral shift that Barnsley had performed in order to compensate for the high pressing wing-back. Presumably down to the success of the back four, Tuchel switched to a flat back four from the static goal kick in the second half. This essentially forced Barnsley to drop deeper from the static goal kick for two main reasons.

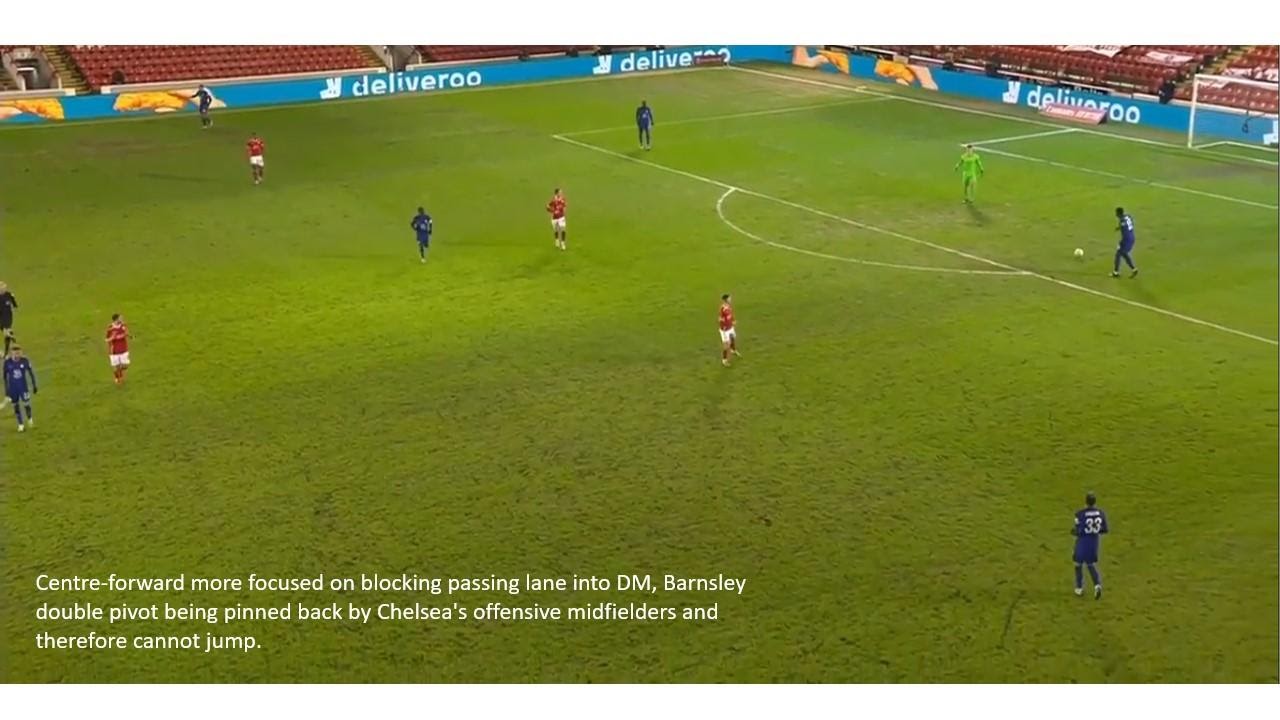

Firstly, the centre-forward’s role changed as a result of Chelsea’s adaptation. Instead of pressing the centre-backs, Woodrow was responsible for keep Chelsea’s lone pivot, Kanté, in his cover shadow because the double pivot behind could not jump forward as a result of the positioning of the two interiors, Gilmour and Ziyech. Thus, Barnsley were essentially forced into a more conservative approach, as cover shadow pressing relies more so on blocking passing lanes rather than pressing the ball aggressively.

Secondly, teams pressing in a back five are more inclined to press high against teams who also play with a back five in possession, in more general terms, because it facilitates matchups all over the pitch (front three vs three centre-backs, wing-backs vs wing-backs etc). However, against a back four, they are more inclined to drop deeper.

For example, the wingers in the 5-2-3 are naturally responsible for the full-backs, who tend to start higher than wide centre-backs typically would in a back three. Therefore, Barnsley began deeper which ultimately led to territory being gained for Chelsea. For the opening 10 minutes of the second half, the central midfielders, or one of (usually the ball side), would only jump forward to press Kanté when Woodrow stepped forward to press the centre-back in possession or the goalkeeper.

This was only common when Chelsea were retreating and recycling possession with the goalkeeper from around the halfway line. Backwards passing is typically a trigger for the defensive block to move forward as a unit in order to relieve pressure.

Woodrow’s pressure essentially triggered a high press, in which the ball side wing-back would jump forward to press the full-back upon reception, thereby ensuing the defensive rotation which occurred in the first half (wide centre-back marks wide players hugging the touchline, rest of defensive line shuttles to compensate).

However, the systematic issue with this, was that the centre-back could not jump out to the free central-midfielder who was abandoned by one of the Barnsley midfielders to accommodate for the high press because the wide centre-back was occupied by the winger on the touchline and the central centre-back was occupied by Tammy Abraham, which in turn, forced the right centre-back to shuttle across to cover and maintain compactness of one flank rather than stepping into midfield.

After just over 10 second-half minutes; the pressing structure was adapted in accordance with Chelsea’s shape as Barnsley looked to engage higher up again. The shape was now essentially asymmetrical across the front line, with the left-winger alongside the centre-forward, and the right-winger a little deeper, essentially on the same horizontal line as the two central midfielders, thereby forming an asymmetrical 5-3-2.

The rationale behind this in my opinion was to facilitate high pressing down one flank (Chelsea’s left) by dropping the winger deeper on the opposite flank. The right-winger would remain deep and close to left-back Emerson, whilst the left-sided centre-midfielder would remain tight on the interior on that flank. This essentially guided Chelsea down the opposite flank, as the players on that flank seemingly had more time and space upon reception as they were marked less tightly from starting positions.

A pass from the goalkeeper or left centre-back to the right centre-back was the trigger for the left-winger press, hence the higher starting position; less distance between the winger and the ball receiver, the quicker the pressure is applied. It was a slight predicament in that the winger had to start high in order to apply immediate pressure upon reception, but he also could not be too close because this would have prevented passes into the right centre-back and therefore the aim of guiding possession down one flank would have failed. The aforementioned defensive rotation then took place.

However, Barnsley failed to nullify possession despite the intensity of this rotation, primarily due to the pace at which Chelsea moved the ball, therefore preventing the backtracking centre-forward from applying rear pressure onto Kanté before he received the ball. This issue seemed insurmountable as the centre-forward simply couldn’t cover the distance between pressing the goalkeeper or left centre-back and applying pressure into Kanté when the ball was at the feet of the right-back.

An alternative solution that would have perhaps required less covered distance was the left-winger, who initiated the press by engaging the right centre-back, dropping deeper once the ball had been played to the right-back in order to block the passing lane into Kanté. An example of this poor rear pressure came in the 57th minute, a passage of play from Chelsea which also highlighted the risks of the defensive rotation and how it can be dismantled by quick circulation and combinations in deep areas.

The ball was played from the right centre-back into the right-back dropping deep on the touchline who was pressured by Barnsley’s wing-back, as the defensive team began to shuttle across to the ball side. The ball was immediately played into the feet of Kanté, therefore preventing the Barnsley centre-forward from backtracking to apply rear pressure as there simply wasn’t enough time to cover adequate space.

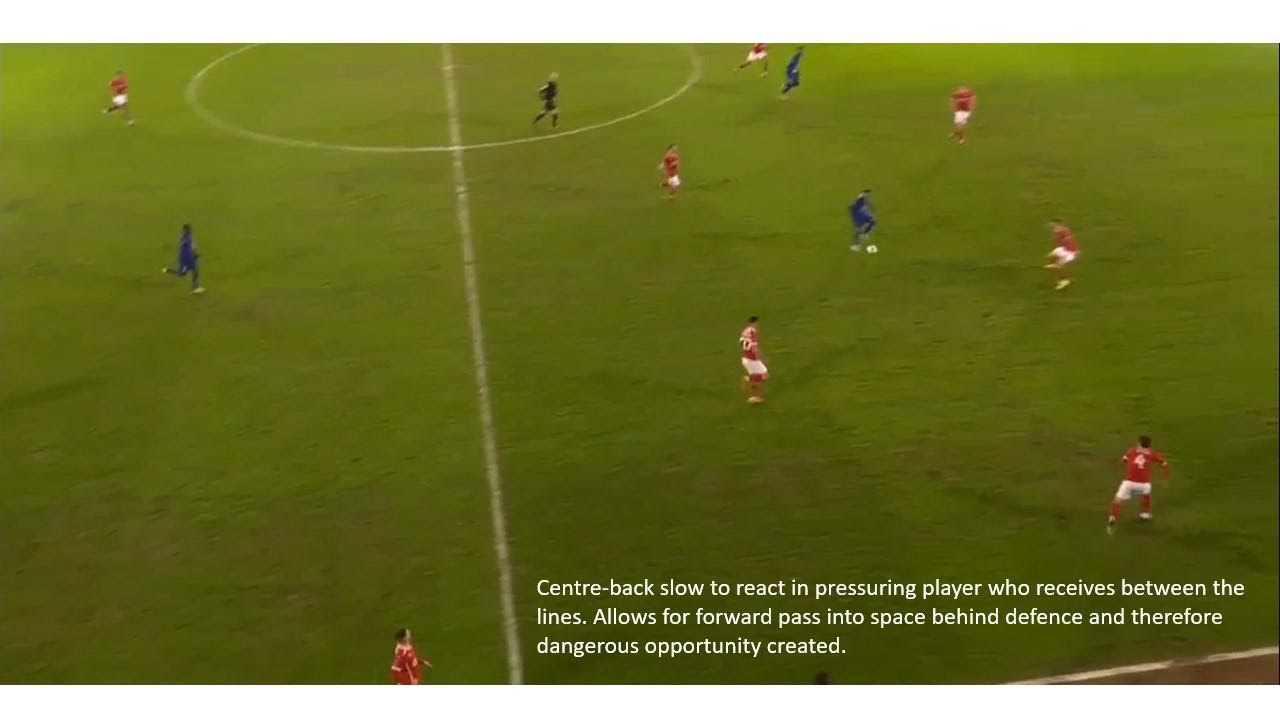

This lateral pass seemed to be the trigger for subsequent movements to take place; Christian Pulisic moved deeper, therefore dragging the wide centre-back forward and into a more advanced position, thereby increasing the distance between the centre-backs, which essentially opened up greater space for Gilmour to dart into from midfield.

Kanté immediately played a vertical pass into the channel with Gimour receiving in space. With the defensive rotation still occurring, the distances between the centre-backs were significant and therefore open to exploitation.

This passage of play highlighted the general concept that man-oriented defensive teams which rely on rotations to quantitatively match the opposition are very susceptible to automatisms or trained passages of play, whereby the opponent knows the next step before performing the action. This was most prominent when Pulisic, the right-winger, dropped deep when Kanté received centrally, with the sole aim of dragging the wide centre-back forward to create space in the channel for Gilmour to move into.

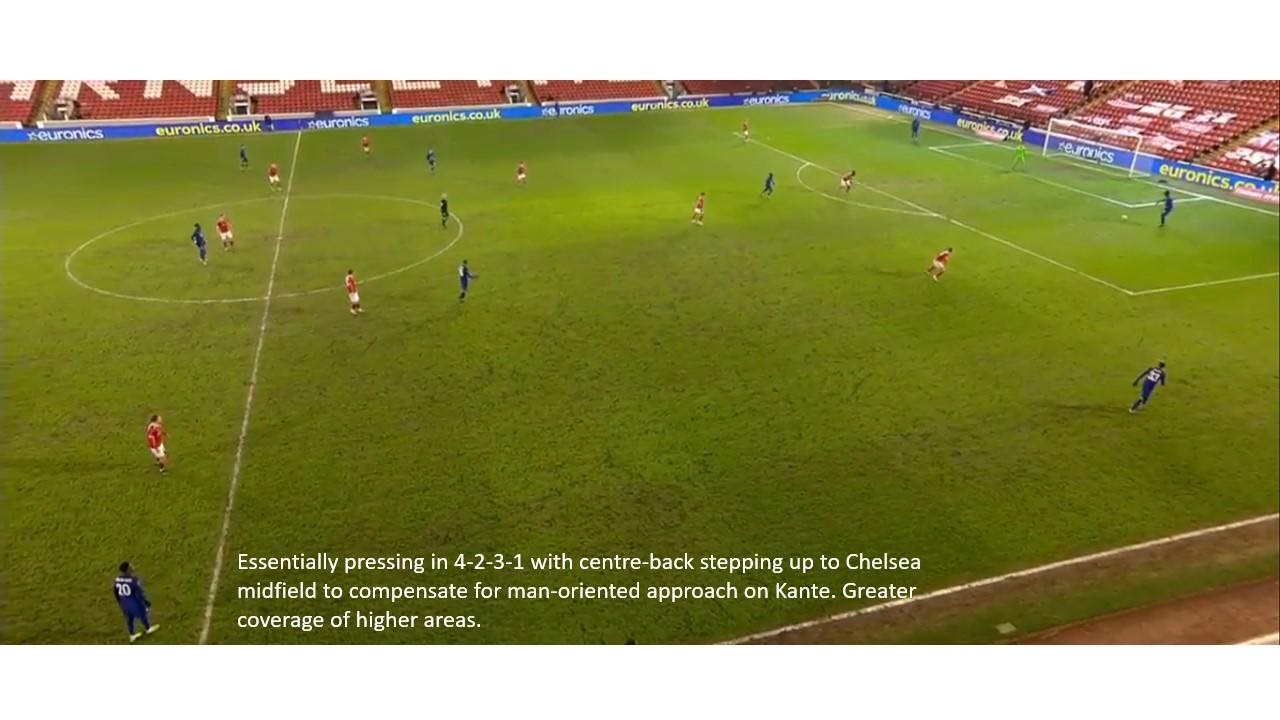

This structure of pressing was utilised until around 10 minutes to go, as a way of aggressively pressing Chelsea, especially when the game state changed with Barnsley chasing the game. The final in game adaptation to Barnsley’s pressing came with 10 minutes to go, as they abandoned the back five which was seemingly an axiom from the beginning, to press in a 4-2-3-1 in the latter stages. I assume this was because the 4-2-3-1 facilitated greater numbers forward and therefore greater coverage of deeper areas (Chelsea’s first phase).

Crucially, Barnsley’s right-sided centre-back stepped forward into midfield from the static goal kick to compensate for the man-oriented approach on Kanté and therefore the lack of midfield coverage as they chased an equaliser. The shape appears the same on either flank, however, the left side was again more aggressive in that the left-winger was responsible for the right-centre back of Chelsea.

As such, this facilitated the defensive rotation of the wing-back stepping up high, whereas on the right-side, the setup was more conservative, with the centre-forward responsible for pressing the ball side centre-back, therefore having a knock-on effect which manifested itself in deeper positioning (right-winger responsible for full-back, right wing-back responsible for left-winger).

The rationale behind this seemed to be to apply constant pressure onto Kanté, who was paramount to Chelsea’s ball progression in the second half. The man-oriented approach is typically more effective than the interchange of roles in applying immediate pressure because the player tracking Kanté has a sole responsibility, rather than having to track back from pressing deeper areas in order to press him. Therefore, the midfielder tracked Kanté tightly for the remaining 10 minutes in an attempt to prevent Chelsea progression.

The outcome was that Barnsley had more possession late on given the game state and therefore became less reliant on their pressing as a chance creation tool. In summation, it was an intriguing battle from a tactical perspective throughout. The game essentially evolved into a battle of attrition which contained multiple in-game adaptations in accordance with the opponent’s shape or ideas.

In my opinion, it further highlights the importance of adaptability in the modern coach. The coach must identify aspects of performance that can be improved, and adapt these in accordance with the opposition’s setup. This tactical battle perfectly manifested this.

By: Ollie Himsworth

Featured Image: @GabFoligno /