Tactical Analysis: Inter’s Wide Overloads

Gian Piero Gasperini’s Atalanta were trailblazers in Serie A with regards to their commitment to achieving wide overloads through using advanced centre backs, featuring drifting forwards and dropping midfielders; however, this season particularly has seen Inter adopt some of the methods used by Atalanta and improve on them through automatising and greater player quality. This article will look specifically at this 4-2-4 transition shape, attempting to explain the theory and demonstrate why it is effective in practice.

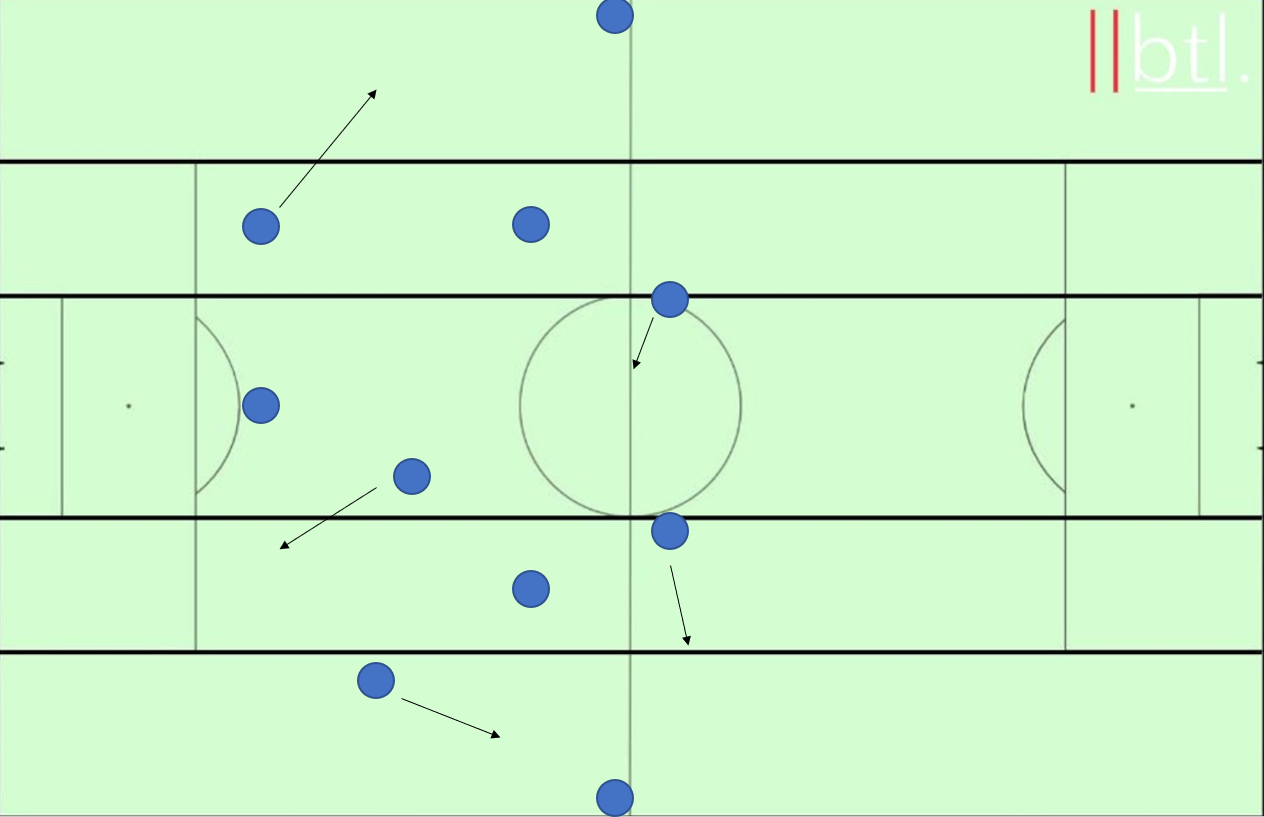

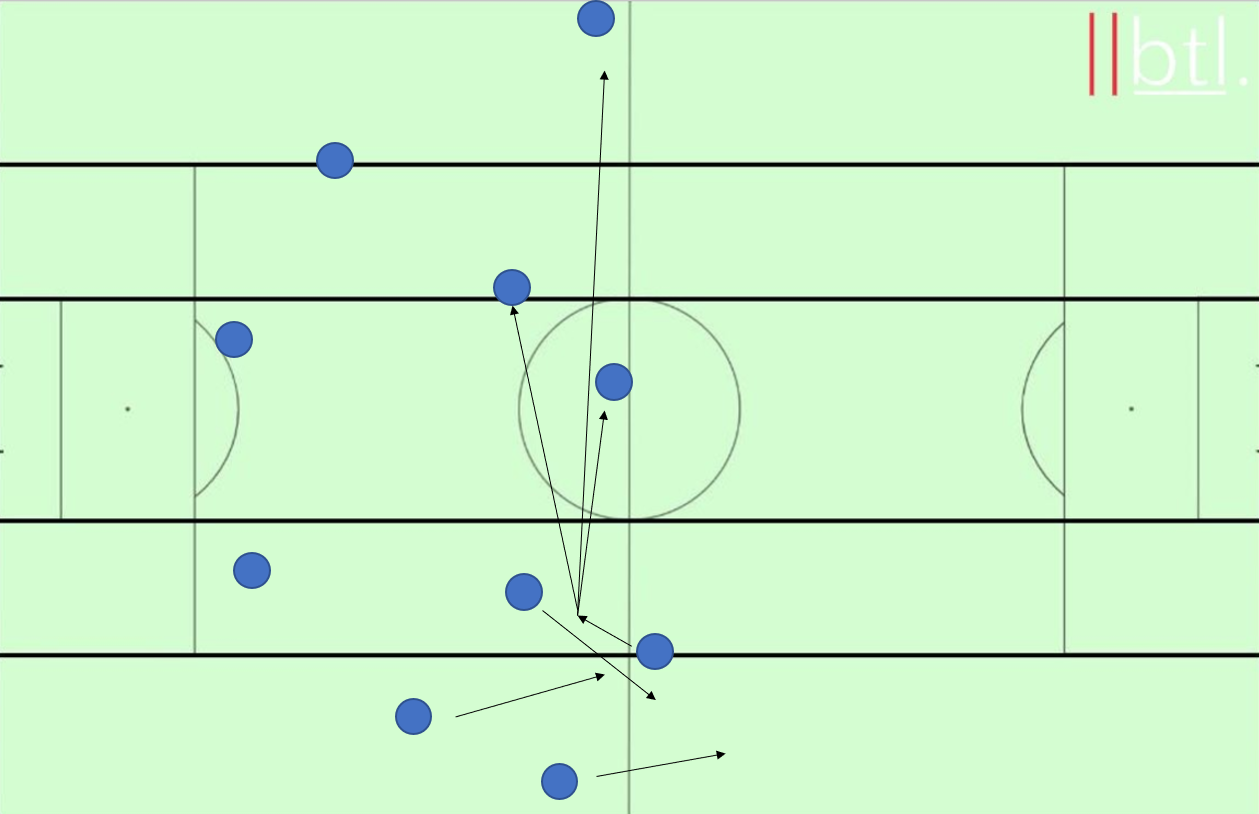

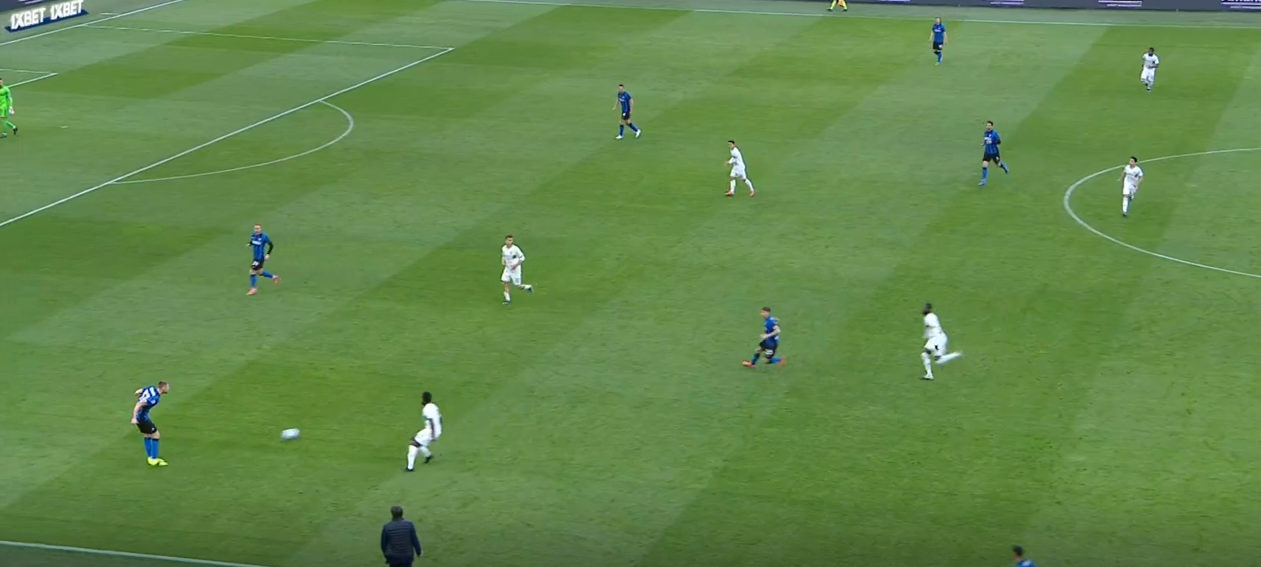

A common pattern of Inter’s to create the diamond shape (shape may not always resemble a diamond but functionally there are four actors involved in a tight interchange with two somewhat vertical and two somewhat lateral) is to adopt the 4-2-4 shape progressively as they are building up.

Dynamic creation of these shapes is paramount because it discombobulates types of defending which use the opposing player as the primary reference point, whilst the motion also acts a trigger towards subsequent actions, guiding the process of the automation.

The rotational aspect is moreover important because Inter perceive centre backs as crucial players towards build-up because they are situated within a diamond of progressive connections with their ability to collect deep and progress with forward momentum posing trouble for opposition compactness.

Progression using wide overloads occurs more frequently on Inter’s right-hand side where they can more easily achieve qualitative superiorities: Romelu Lukaku is better at receiving with his back to goal, and running at defenders into space compared to Lautaro Martínez, and Achraf Hakimi provides a greater threat when running in behind a defensive line compared to Inter’s left wing-back options.

Nicolò Barella is technically accomplished while providing an intensity typically not seen by Christian Eriksen which adds dynamism as the responsibilities of the respective players can be more diverse due to an additional direct threat, while Milan Škriniar is good at progressing the ball via dribbling, perhaps the most important possession skill for the centre back in this set-up as typically difficult passes, particularly long-passing is not required due to the move being predicated on short interchanges to open up space.

While Alessandro Bastoni is better on the ball than Škriniar in general abstract terms, within the context of this automatism, Škriniar is better suited. Additionally, after the flank has been overloaded, Bastoni often gets space to maraud into should a switch occur which allows him to better display his possession potential from early crosses for example.

Moreover, Barella and Škriniar are particularly important for the counter-pressing aspect, which is used after a possession turnover due to the compact spacing of players attempting the overload. Škriniar is a proficient tight marker that can be a tool used to halt forward progression, regain possession, or commit a tactical foul to break up opposition counter-attacks, while Barella’s aforementioned intensity makes him well suited for the more frenetic game-state following a turnover.

The centre backs pertinently occupy the deep-full back position. This zonal occupation causes issues for the pressing team because it horizontally and vertically stretches as the deep construction element prevents maintenance of compactness when attempting to pressure because of the limited forward progression options of the first line, while the wider positioning increases gaps in between the lines horizontally temporarily while the opposing team shuttle.

This could be done with reticence holistically because of the ease of access of central back passes exposing the compactness via switching play, making more individual presses a better option for an opponent looking to maintain pitch coverage.

Furthermore, reduced vertical compactness serves to reduce the effectiveness of horizontal compactness as wide actors become more dangerous if they receive possession as they can more easily move the ball inwards due to the increased space for central passes in between the vertical’s lines. This means there is a symbiotic relationship between the two forms of stretching which amplifies the efficacy of deep construction.

This is particularly effective against high-pressing sides because long passes expose compactness through reduced pitch coverage which can then allow for inward progression to be made as space has been exposed or alternatively, get the opponent to overload resources in response to the switch resulting in an up-back and switch rather than up back and through although as denoted by the naming, the broad principles being the same.

Therefore, the opponent is either forced to relinquish control and not pressure thus allowing for the establishment of control because of the subsequent necessity to drop. Hypothetically, if they want to maintain similar levels of compactness while simultaneously attempting to engage in deeper regions, they would potentially be conceding enough space to make a direct ball a threat.

Alternatively, they can push higher while maintaining their defensive line which exposes greater space in between the lines, something which forward momentum and rotations capitalise upon because the player moving forward, and rotating carries the initiative and thus is in front of his reactive marker. Pertinent with regards to this example is the pinning effects the forward line has upon their opposing markers as the forward line of four force deeper opposition positioning through their high relative positioning which is often still in their own half allowing for (lack of) offside to be exploited.

Moreover, the time and space generated through deep, wide positioning makes staying (very) high unlikely even when offside is exploitable because of the principle of dropping when the ball carrier is unpressured and can potentially play a penetrative pass. Therefore, Inter use two mechanisms of vertical stretching the facilitate the space in between the lines required for their short interchanges once the diamond has been established. These more theoretical elements provide the conditions necessary to practice the automatism.

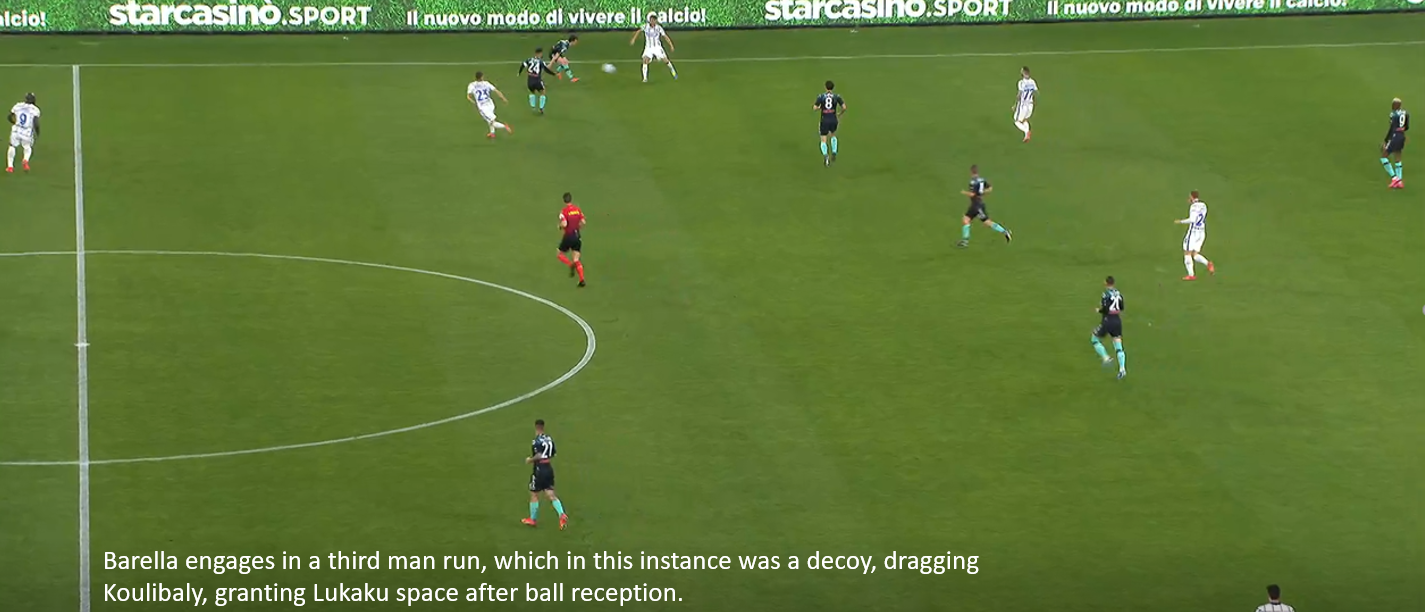

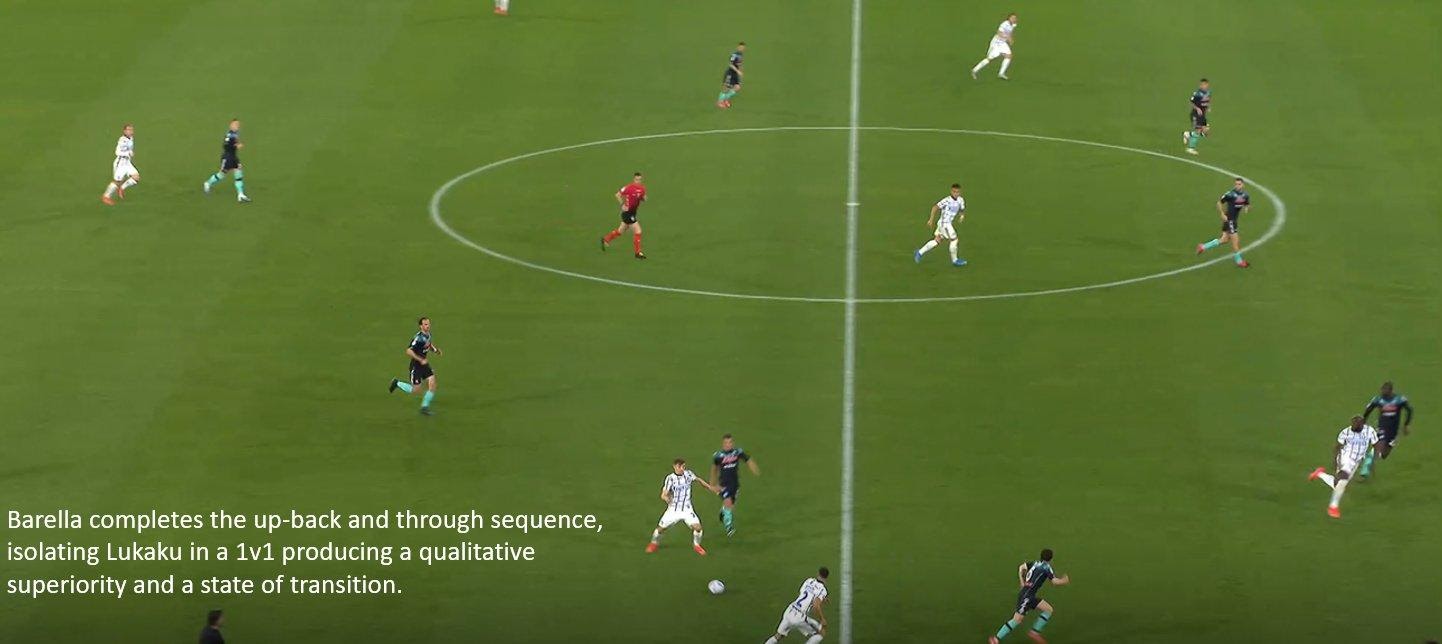

Throughout, the focal point, is Lukaku who is tasked with holding possession to facilitate runners, his reception allows either Barella or Hakimi to receive possession with forward orientation thus exposing the oppositions last line, while the other who did not receive possession makes a third man run, meaning the up-back and through/switch sequence frequently occurs.

These principles are perhaps more important than the automatisms when viewed in isolation because they allow for the occurrence of spontaneous automatisms (not generated through deep consolidated possession), whereby, although the sequence occurring is different from how it would be devised when in control of possession deep, the principles derived which make the automatism successful can be placed into action allowing for the sequence to remain quick, fluid and hence effective.

These sequences are facilitated by overloading the half and wide spaces which can be achieved in Inter’s case using a 3-5-2 by the wide CB, CM, and FW sitting within the half-space while the wing-back stretches play horizontally – this particularly when combined the dropping CM to create the 4-2-4 shape through freeing the centre back frequently leads to a more vacated centre and the opening of isolation opportunities on the opposite flank.

This creates two wide diamonds, or triangles depending on the point of effective connection (sometimes the centre back is superfluous, making the triangle the relevant point of analysis, as the backwards pass can often go uncovered) whereby forward momentum is exploited for swift interchanges. The primary aim is to progress via these overloads achieved, largely ignoring the central zone unless to provide a connection for a switch when transitioning and beginning the process from consolidated possession to transition.

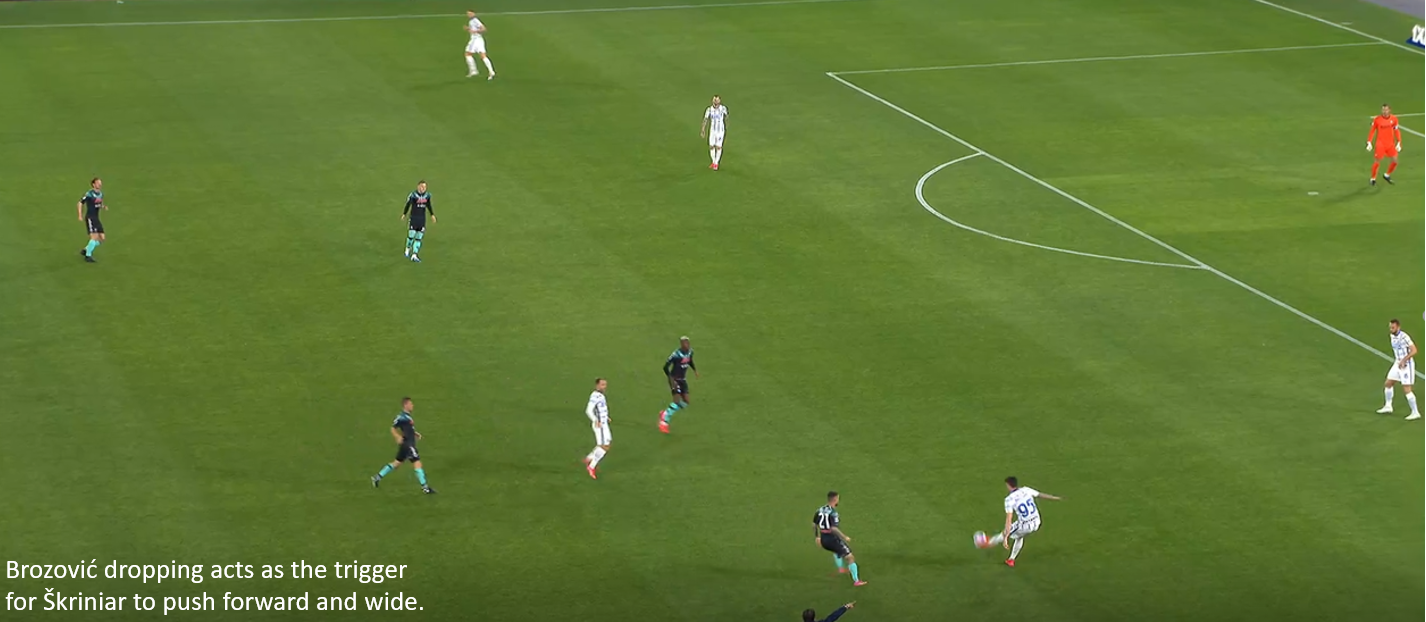

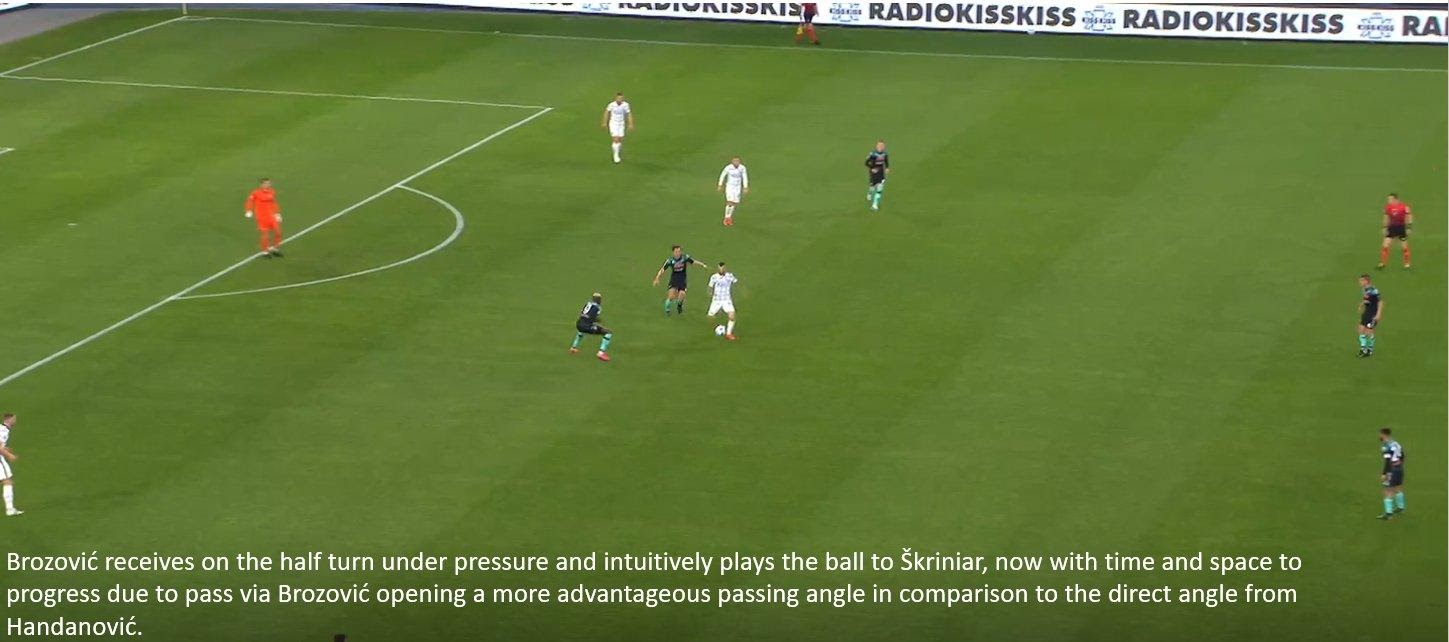

To provoke a series of potential automatisms, often Marcelo Brozović drops into the defence while Škriniar splits wide to become a deep full-back establishing a vertical link to the now advanced right wingback. Bastoni typically occupies this positioning from deep consolidated possession.

The dropping central midfielder can drag an opposing marker which can reduce the opponents central/potential half-space cover temporarily, although this is not necessary, as even against a more zonally oriented system, confusion is caused due to the displacement caused by wide centre back movement in addition to the reactivity creating a disadvantage as the wide centre back is one step ahead, generating the time and space necessary to pass.

This works against the two primary types of pressing schemes roughly speaking (tailoring of the respective strengths is required against specific examples rather than abstract zonal and man systems) as against man-orientation the movement drags markers, upsetting defensive coverage, whereas against zonal defences, overloads can be achieved which allow the ball carrier time and space to expose potential lack of vertical coverage or otherwise force a retreat, opening space in between the lines.

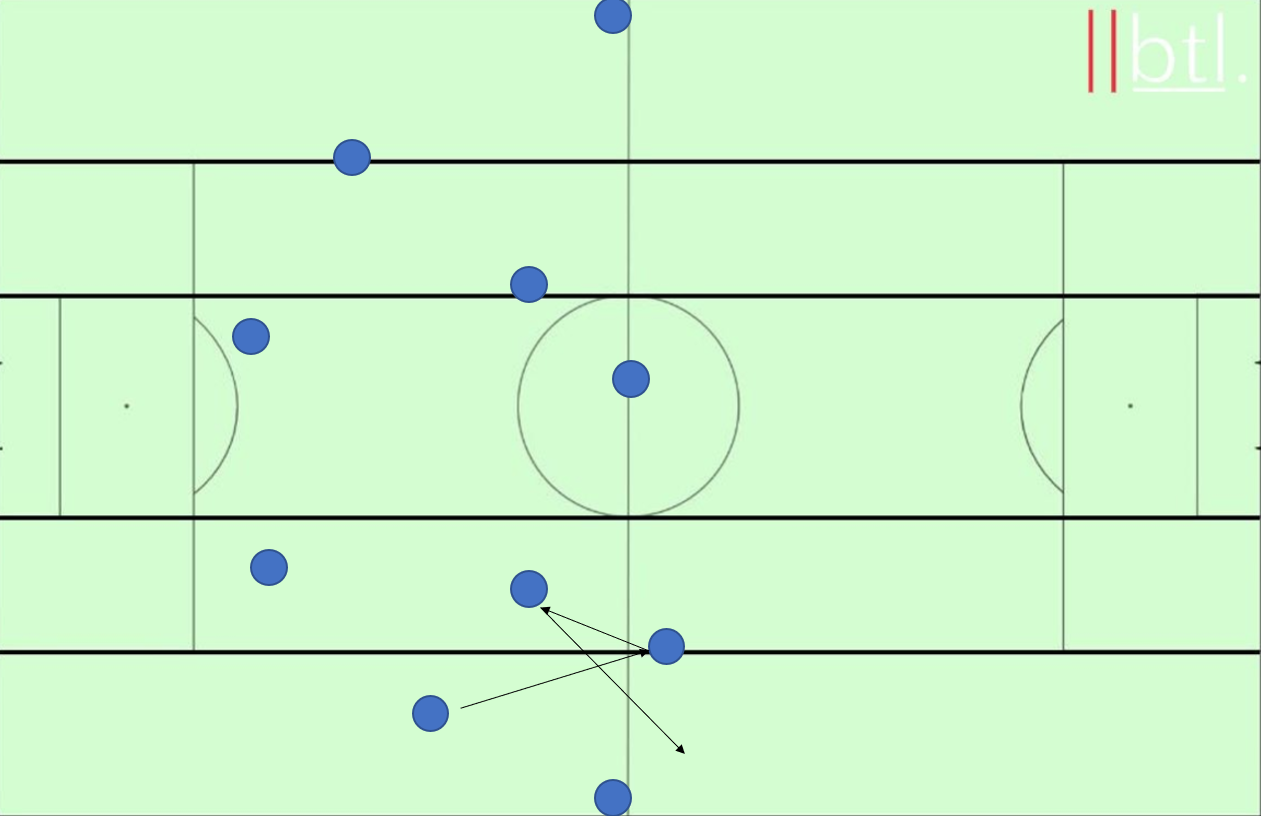

This opens three common advantageous situations. Firstly, the up back and through using the wing-back is simplistic, but nonetheless exploits the short passing network to spring an attack against a man-oriented defence confused by the third man movement and manipulated to the varying depths of movement – Lukaku backwards opening space, Hakimi forwards exploiting space.

The up and switch is where juxtaposing movements of either/simultaneously of Barella and Hakimi draws the opposition’s defence back to cover potential up-back and through situations where rather than attempting to exploit opposing lack of vertical coverage, they expose the lack of horizontal coverage through affording Lukaku time on the ball via the decoy runs to switch it to the other flank.

On the other hand, in some instances they continue to run at the opposing defence as they attempt to cover all passing options, leaving the Belgian striker free to run in between the lines, as the opponent’s last line is continually dropping.

This was seen against Napoli here, where Barella runs in behind, overloading Kalidou Koulibaly, who prioritises preventing the up back and through sequence, therefore, generating time for Lukaku who exploits the increased space in between the lines to dribble forward, ultimately finding Matteo Darmian in a dangerous position in the box.

A third potentiality is created when the staggering between the wingback and central midfielder is sufficient as to create a zig-zag sequence where the ball from Škriniar goes in, (Barella), out (Hakimi), out/in (Lukaku) or alternatively wide first into an up-back sequence (Hakimi to Barella) – and staggering of this sort from players in between the lines opens up more passing lanes in between the lines when the ball is active.

This creates gaps between opposing players defending the region because they become more split attempting to cover all possibilities resulting in increased space to move into which does not negate efforts made through playing behind the line in this instance staying in between the first and second rather than moving back to the first.

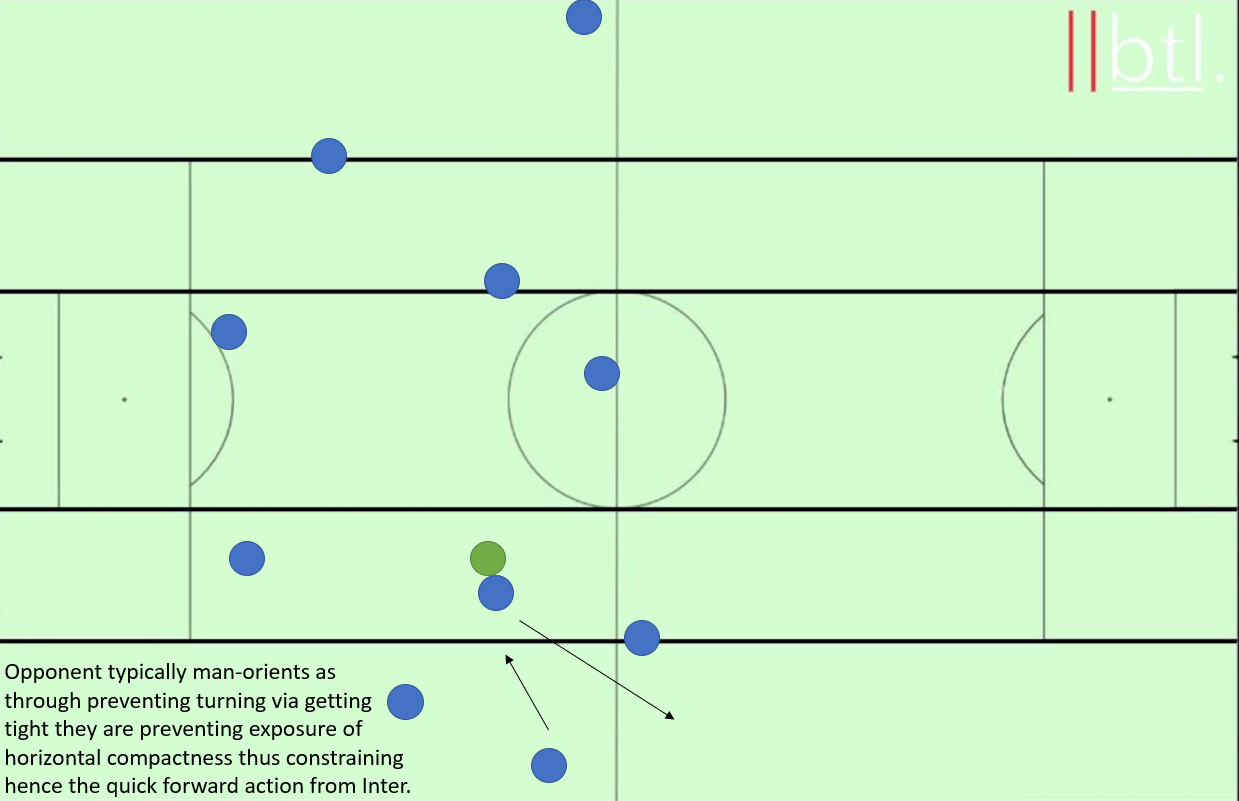

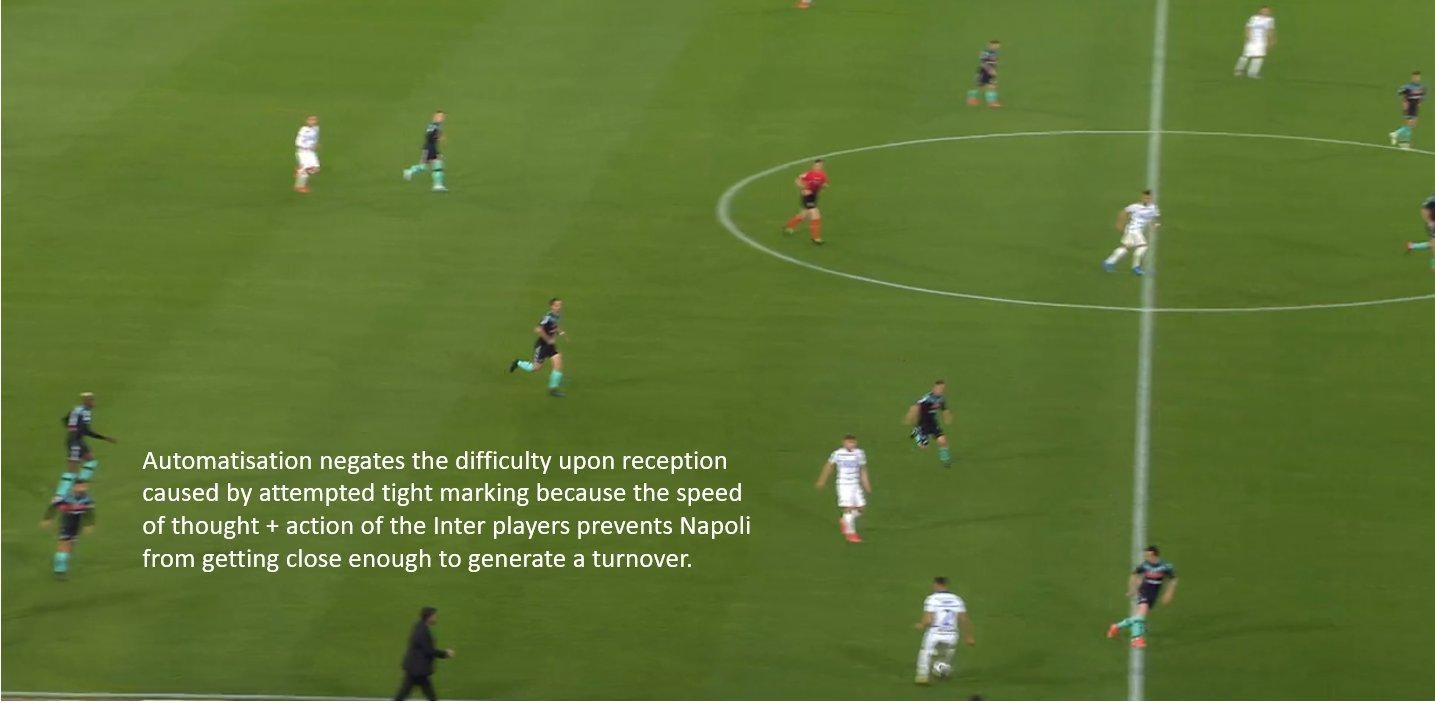

Moreover, this passing exchange typically results in a quick, thoughtless pass (used positively to describe the effectiveness of the automatism as the players know the option available) as to respond to typically man-oriented pressure which seeks to constrain through exploited the tight passes on the flanks to make ball reception/horizontal opening of the pitch difficult.

Automatising this particular pattern is crucial because the opponent typically seeks to exploit the short, somewhat later passing distance in wide regions to constrain and thus man-orients as to prevent turning upon reception (provided its successful) forcing play down the current flank. This means exploitation of space must occur vertically through Lukaku running in behind where a 1v1 situation is created, of which he is often the victor.

This pattern therefore seeks to create a qualitative situation, where not all situations of numerical equality are considered equal. It is probably the least dangerous of patterns because the 1v1 situation occurs on the overloaded side, and Lukaku often must make inroads from wide areas. It nonetheless is advantageous.

This can be seen against Napoli where, initially the forward momentum of Škriniar in conjunction with Napoli’s central prioritisation leads to him having space to move forward into, which provokes Lorenzo Insigne to pressure creating time a short window of time for Barella to receive before Diego Demme is too tight.

Insigne’s initial distance is required to maintain compactness as to prevent the direct vertical pass to Barella who would subsequently have space to move into, demonstrating the utility of depth provided by the ‘deep full back’ positioning of Škriniar as it generated time and space to progress into.

It is difficult to demonstrate the speed of action and thought from Barella through images, but it highlights one of the fundamental benefits of automatised play which is being able to think ahead when playing actions and having a preconceived notion of what is going to happen which allows quick action to be undertaken rather than time being wasted scanning the area and coming to a contextual conclusion which grants the opponent more opportunity to react.

Without the action of the Hakimi pass implying the subsequent action of the quick ball to Lukaku who had preemptively started his run, it is difficult to envisage a sequence like this occurring spontaneously. The theory behind Napoli’s defending made sense, Insigne will cut the pass diagonally covering Barella directly while pressuring Škriniar, who is forced down the line into a pass to Hakimi who has one option, Barella, who Demme is about to pounce on, creating a turnover through isolating options progressively. It was the quality of Inter which allowed this sequence to occur rather than poor defending from Napoli.

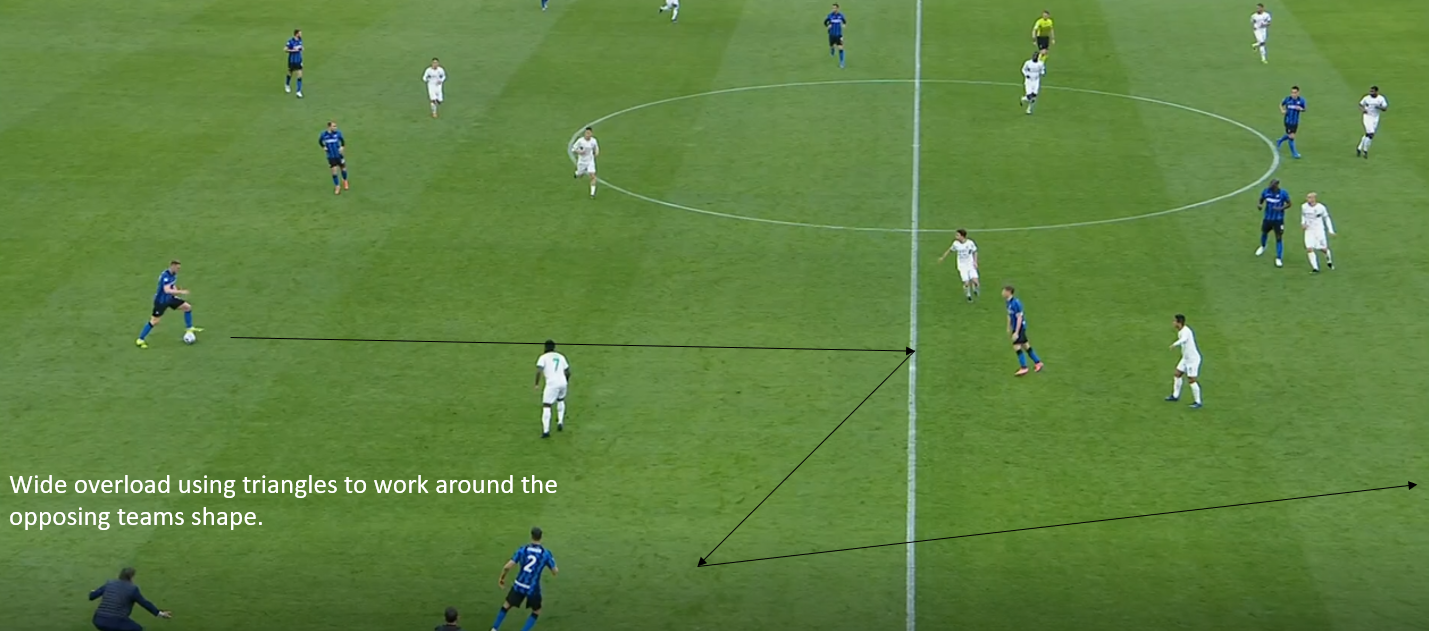

Inter are the side this season, which seem most adapted to increasingly prevalent pressing style which is a ball-sided, man-oriented ball-sided 4-2-3-1 which transforms to ball-orientation once the ball carrier is isolated (to see a more detailed analysis of a particular game – Destroying Man-orientation: Antonio Conte Style – Breaking The Lines).

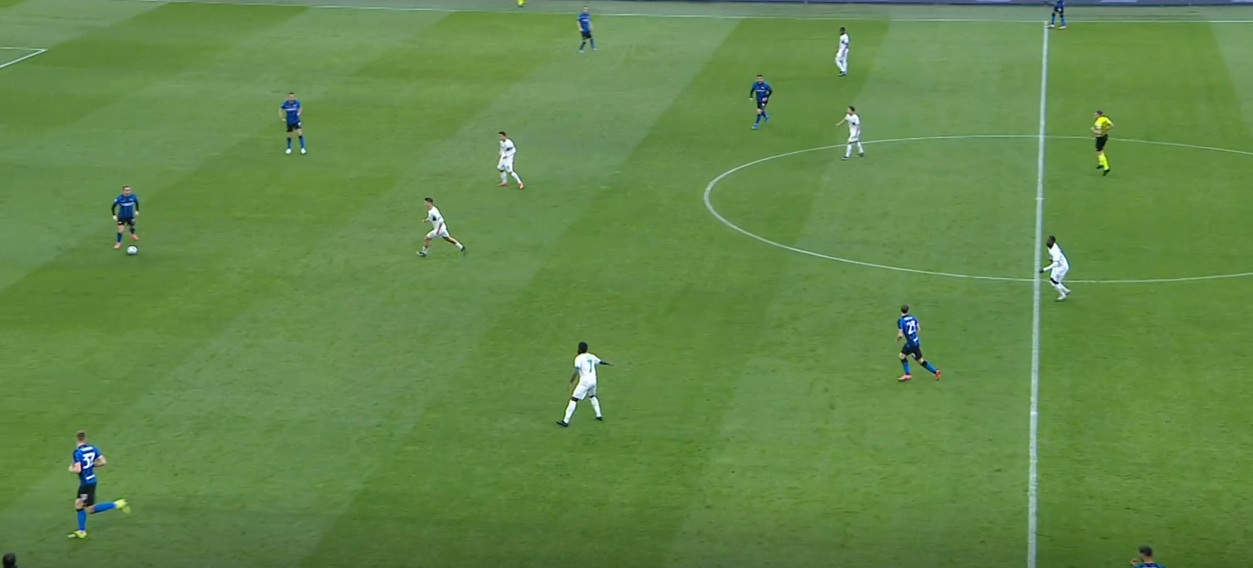

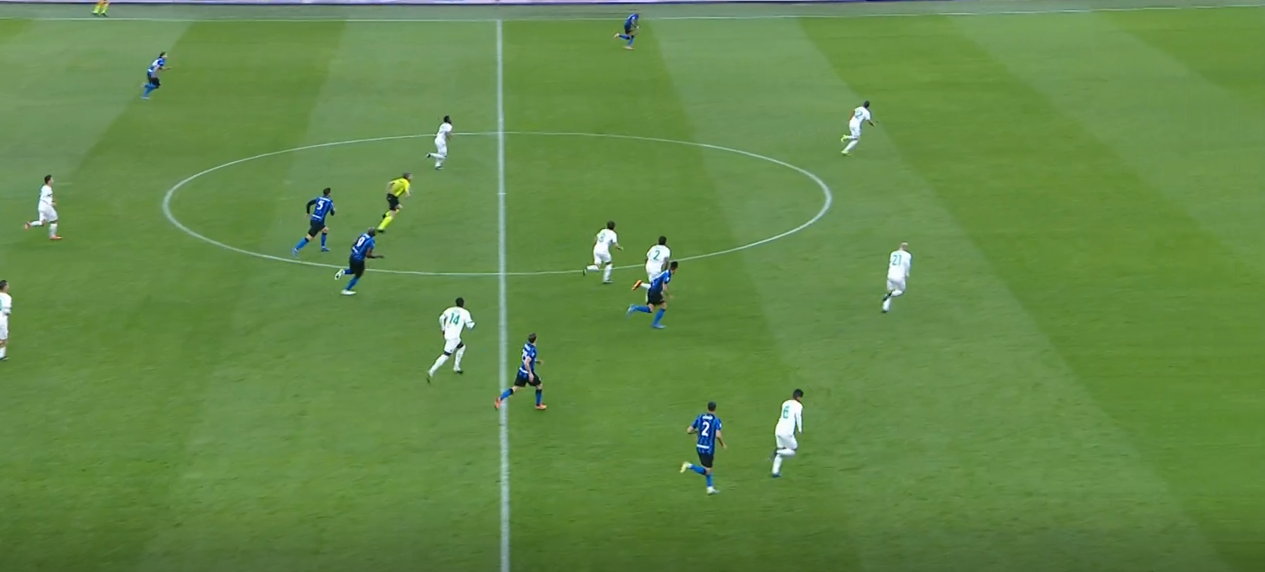

The sequence Antonio Conte chose himself to highlight the 4-2-4 automatism, which seems an apt place to ends the article, occurred against Sassuolo who use a pressing system that could be categorised according to the aforementioned description.

Škriniar drops deeper to increase the distance between him and Barella giving him time in possession as Jérémie Boga needs to maintain compactness between himself and Pedro Obiang as to prevent Barella receiving directly which would subsequently open the passing lane up to Škriniar afterwards. Hence the necessity to allow the pass before jumping to man-orientation of the ball-side.

One touch in from Škriniar, one touch out from Barella, one touch in from Hakimi demonstrating the automatised nature as they play around Sassuolo’s attempted containment through gradually compacting the effective pitch via man-oriented ball side pressing, capitalizing on the compactness needed for the man-oriented ball-sided pressure through exposing lack of coverage.

In conclusion, time in possession is what exposes compactness; however, not all seconds are made equal, the amount of effective time an Inter player has during an automatism is increased because the comprehension and decision is pre-determined meaning measures that attempt to limit time on the ball are less effective, whilst their downsides, namely, lack of pitch coverage get exposed, nonetheless.

When each action implies a subsequent action, Inter are usually one step ahead of their opponent which is what makes their space exposure (up-back and through/up-back and switch) so effective.

By: @mezzala8

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / Gabriele Maltinti / Getty Images